Forget for a minute those precious (plastic) boxes of a dozen pretty edible flowers that you sometimes find at the grocery store for $25. Yeah, right. You pass those by, I know. But maybe you’ve plucked a few Johnny jump up or pansy blossoms from your yard to decorate cupcakes, or added nasturtium blossoms to your salad. Let’s just say you’re vaguely aware of the most obvious benefits of edible flowers – beauty and flavor (some admittedly more tasty than others).

I would add a third benefit. Incorporating the flowers of edible plants into your recipes and menus will not only help you become more aware of the life cycle of plants; it will allow you to use more of a plant than just one part of it, ultimately cutting down on waste.

I’ll use cilantro to illustrate my point.

Every year I hear the same lament from friends with kitchen gardens: “I can’t grow cilantro! It just flowers and I never get very many leaves.”

First, it’s important to understand that cilantro loves cool weather and will automatically “bolt” (send up long stems with a much finer foliage and little white lacey flowers) when the days – and the soil – get hotter. It wants to flower so that it can then produce seeds before it succumbs to the heat.

To get as much foliage as you can from your plants, sow the seeds as soon as the soil reaches 60 degrees, sow a lot of seeds (a whole row, not just one or two), and sow them close together (this will help keep the soil cool). Harvest often and nip off the first flower stems when you see them. Then, do what the pros do: succession planting. Sow another batch of seeds a week or two after the first batch – and repeat again if you can before high summer. You’ll be able to harvest the foliage of the youngest plants while the older ones are going to seed.

Inevitably, you’re still going to go into the garden one day and discover you’ve got tall, wavy, wispy stems of flowering cilantro all over the place. Here’s where you need to change your mindset.

If you did nothing else but leave the plants there, that would be a good thing: flowering cilantro attracts beneficial predatory insects. But you can most certainly continue to harvest from the plant – the flowers, the finer (sparser) foliage, and the tender stems are all perfectly edible. Use them exactly as you would the larger leaves, chopping them coarsely. You won’t have as much volume, but you will still have some cilantro to use.

Even better is to leave some of the plants alone – you’ll soon see small, round green berries forming on the plant. These are immature coriander seeds, bursting with a bright, fresh, lemony flavor. I use them whole or slightly crushed in salad dressings, pestos, salsas, vegetable stir-fries, curries, braises, and more. Any green berries left on the plant (and there will be many) will mature, turn brown, and dry by the end of the season. Voila, you have your very own coriander seed. Store it whole and grind it in a coffee grinder when you want fresh, fragrant ground coriander for a recipe.

By the way, young coriander roots are edible too. Milder than the leaves, they’re a star ingredient in Thai curry pastes and other Thai dishes.

Sure, not every plant with edible flowers is as generous as cilantro. But in the realm of kitchen herbs – ones you could grow even if you just had a few pots on a deck – there are many that offer both tasty leaves and flowers. And herbs actually benefit from pinching (removing the flowers) as it allows the plant to put energy back into its leaves. One important note: only eat flowers that you are sure have not been treated with pesticides. If you buy a plant from a nursery and aren’t sure, pinch off the existing flowers and also transplant it to refresh the soil. Eat the new flowers as they appear.

Here are a few more of my favorites:

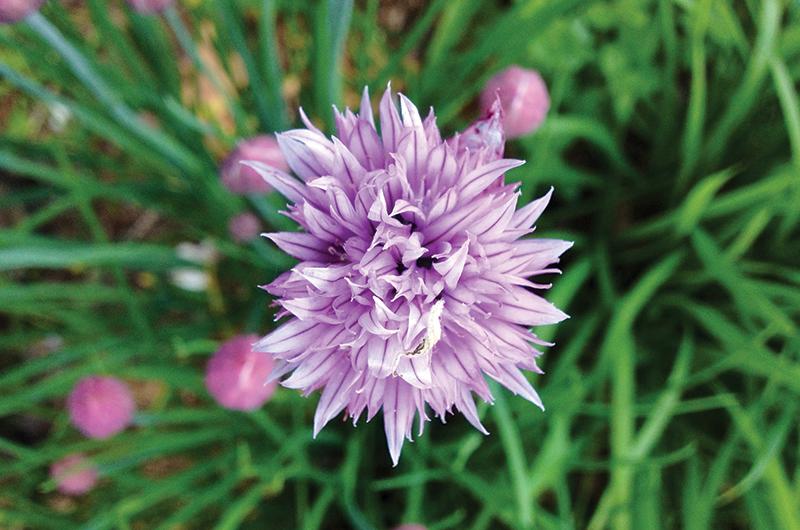

Chives and garlic chives. The cheery purple pompoms of flowering chives are one of the first edible flowers to appear in the garden in late spring and early summer. The beautiful white globes of garlic chives show up later in the summer. You’ll want to pick garlic chive flowers both to enjoy their pungent flavor and to prevent rampant self-sowing when the flowers produce heavy black seeds. To gather allium blossoms, use your thumb to pinch the cluster of tiny stems under the pompom, and you’ll have dozens of tiny flowerets. Discard the tough main stem. Chives and garlic chives both have strong onion-y flavors; I use them to perk up scrambled eggs, frittatas, quiches, savory tarts, and other egg dishes.

Basil, Thai basil, and other specialty basils. I admit that I’m fond of basil varieties that flower prolifically (Mrs. Burns lemon basil, cinnamon basil, aromatto basil, and certain varieties of Thai basil) as I use them not only in the kitchen, but also for flower arrangements. But I truly love the tiny buds that form up and down the flowering stems before the flowers open – they are spicy little flavor bombs. I strip them off right into the salad bowl, over sliced ripe tomatoes, or into a vinaigrette. All summer long I throw whole basil leaves and flowers of every variety into weeknight veggie stir-fries, and I miss them terribly in the winter. If you’re not growing basil, stop by Ghost Island Farm in West Tisbury for farmer Rusty Gordon’s robust basil, which often has some flowering stems with it.

Mustard, kale, and arugula flowers. Here’s another case where folks go crazy when the lovely greens they’ve tended in the spring garden suddenly bolt, shooting up stems covered with small yellow (or white) flowers. Sure, you’d rather have big, tender leaves, but the flowers are bright hits of summer, lovely to add to quick pickles, salads, and creamy spreads made with goat cheese or fromage. The stems will also continue to sprout smaller leaves you can harvest. Some of these will be spicier, so be aware. Bolted arugula leaves can be quite bitter, but the cross-shaped white flowers are mild.

Nasturtiums. It would truly be a shame if you thought of nasturtiums as just a pretty, colorful flower. The entire nasturtium plant is edible – leaves, flowers, and seeds – and it provides Vitamin A and Vitamin C, as well as many benefits as a companion plant in the garden. Nasturtiums attract beneficial insects, act as a trap for pests that bother tomatoes and other vegetables, and pollinators love them. I always plant dozens of nasturtiums in my vegetable beds. They aren’t related to watercress, but they sure taste like they are. All summer long I harvest the leaves and flowers for salads – especially warm salads with grilled meat. I use them as a grilled pizza topping and with Asian noodle dishes too.

And many more. You’ve got a true bouquet of choices when it comes to plants that offer edible flowers. Some of my other favorites are pineapple sage, borage, calendula, dill, rosemary, thyme and oregano blossoms, lavender, scented geraniums, gem marigolds, dianthus (pinks), squash blossoms, and more. In years when my peas go crazy, I also help myself to pea blossoms before they set fruit – or even when they have a tiny pea attached to them.

While eating the flowers raw in salads and as a garnish is lovely, I encourage you to coax out their flavor by allowing them to infuse other ingredients. This is why I recommend adding flowers to any kind of egg-based custard (like the savory pancake batter in the recipe at right) or creamy, spreadable cheese. But flowers can also infuse sugar, vinegar, oil, alcohol, or tea. Use them in salsas and marinades. You don’t need to treat them with kid gloves. Like your best china, they should be used every day.