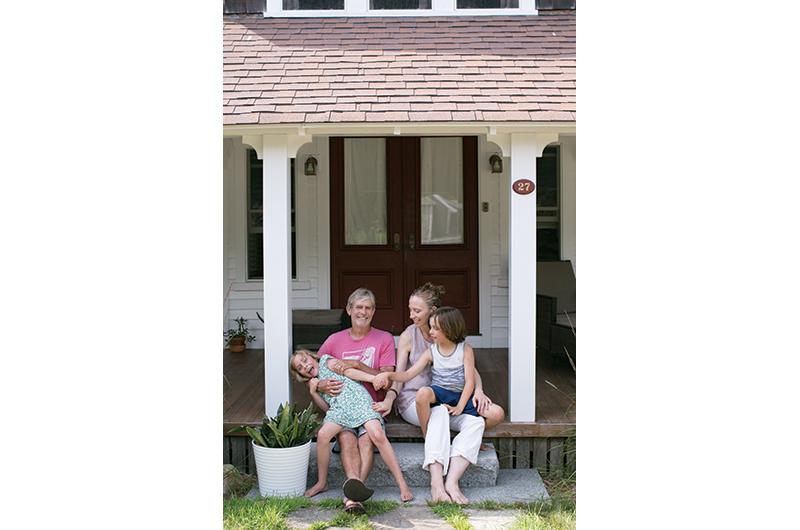

The term “zero waste” might be new, but the philosophy behind it is old and venerable – much like the solid early-1870s house in Oak Bluffs where Nina Carter Hitchen, her husband Peter, and their family manage to live their full lives while producing astonishingly little trash. Consider this: the average American produces about four pounds of garbage a day, but Hitchen’s family fills a mere one gallon glass jar of household trash once a month.

“Our culture just buys things off the shelf,” Hitchen says, “and then our waste removal system is so efficient; there’s so much that’s out of sight, out of mind. We typically don’t see things again, unless it’s street litter or washed up on the beach.” This insight, she says, “affects what I eat, what I wear, what furniture I buy, products I put on my skin, everything.”

Hitchen, an interior designer at Vineyard Decorators and founder of Plastic Free on MV, a group dedicated to reducing waste and consumption of plastics, has mastered the art and discipline of waste-free living. But the challenge to do more with less is endless. “I keep thinking of all the things I’m still not doing,” she says.

And yet she’s already doing a lot in a limited amount of time. In addition to her full-time job, Hitchen is mother to eight-year-old twins Dylan and Ondine. Days are spent helping them with homework, jumping in mud puddles, looking for wildflowers, or taking walks on the beach. “Life is crazy at the moment,” she says.

Hitchen’s waste-free homesteading approach has “all happened in stages. I was raised by hippies. My mom alerted me to the harmful health effects of plastics when I was pregnant and it has continued to snowball.…As an undergraduate, I started as a biology major at Brown University and then worked as a naturalist on a whale watching boat [for the Pacific Whale Foundation] in Hawaii. Back then, neither that organization nor I were thinking about plastic in the ocean. We both are now.…It’s all just come together.”

On the kitchen counter sits a stainless steel water filter that removes toxins, such as heavy metals and microplastics, providing water for their cooking and drinking. “We’re not millionaires. I asked for that for Christmas one year.” Next to the sink is a bar of castile soap in a dish with a wooden scrubbing brush. “Plastic-free versions are always prettier,” she notes. Underneath the kitchen sink, instead of the usual messy collection of cleaning products with questionable ingredients, is a glass bottle of vinegar that is used for everything from cleaning to gardening to home remedies.

Kitchen tools and utensils are all made of metal or wood so they can be recycled or biodegrade. “When a plastic bowl breaks, it will stay in the world for hundreds of years,” she says.

Her refrigerator serves as a shining example of how to feed your family with utmost ecological care. She buys milk in glass bottles (because paper cartons are lined with plastic), uses stainless steel leftover containers, and wraps a variety of vegetables in white flour sack cloths, which can be purchased from LeRoux at Home in Vineyard Haven. “My kale keeps for fourteen days like that,” she says, noting that simple cloths are also cheaper and more versatile than specialty cotton bulk bags. She makes her own yogurt and tortilla dough and stores deli cheese in Pyrex containers.

The pantry, meanwhile, is streamlined with matching glass jars of staples like flour, sugar, baking soda, and pasta, which she buys from bins or in bulk. Bagels for the week are bought loose at Cronig’s Market and stored in a pillowcase in the freezer. Sesame sticks, nuts, dried fruit, and other snacks are purchased in the bulk section and kept fresh in mason jars at home. She knows which butter is wrapped in compostable wax paper and which is not.

When following a recipe, Hitchen takes stock of whatever is in her pantry rather than running to the store for a specific item. “Why buy a long list of ingredients that I may only use once and will probably go bad?” she says. When

using a recipe, if she is missing something, she usually substitutes with an equivalent she has on hand. At the grocery store, this approach can mean saving money. According to internationally renowned zero waste expert Bea Johnson, author of Zero Waste Home: The Ultimate Guide to Simplifying Your Life by Reducing Your Waste (Scribner, 2013), packaging accounts for approximately 15 percent of what an item costs, and every time consumers buy something, they’re voting for the kind of world they want to live in. Hitchen, who credits Johnson with inspiring her own efforts, agrees. “When you buy something packaged, you’re saying that’s okay. More competition will bring prices down as it has with organic produce.

“Yes, some items like loose apples may be a little more expensive, but when I think of my approach, I save so much money on disposable things I no longer buy: coffee filters, paper towels, trash bags, art paper for my kids, gift wrap, greeting cards, Ziploc bags, Saran wrap. I don’t have excess money, and don’t want to waste it on things that will get thrown away.” Not to mention the reality of then having to pay to throw an item away at a landfill.

“I think about everything we bring in,” she says.

The result is a clean and simplistic approach to living. Wooden cutting boards, a houseplant, and a chalkboard are this kitchen’s décor highlights. Script writing on the tiny, old-fashioned chalkboard announces the family’s meal plan. This week it’s eggs on Monday. “I’m not really a cook. That just means a crust-less quiche with whatever unpackaged vegetables I find at the store. Maybe that’s called something else? A frittata?” she wonders, flashing her huge smile.

A mostly vegetarian diet helps with the waste reduction because meat packaging is often not recyclable or compostable. “I’m always thinking about what kind of waste a meal will create. We don’t like to rely on recycling, plastics especially. Most [plastics] can only be recycled once, if that.”

Friday is pizza night; Hitchen often makes three dough balls at once and freezes them. “It’s fast and easy,” she says, crediting Johnson for the recipe. “If you don’t want to make the dough yourself, most pizza shops will sell balls that you can transport in a reusable container.”

The meal plan is one of Johnson’s ideas as well. “Most people don’t schedule in a leftovers night, but that helps us be true to making the most of what we already have,” Hitchen explains.

Sometimes, she says, there’s no perfect solution, so it’s more about finding the best substitute. Since the twins beg for cereal, she buys a healthy kind that comes in extra-large bags without a cardboard box. The children help zero waste efforts in the afternoons by eating their lunchbox leftovers as after-school snacks. Anything left, like carrots or snap peas, are rinsed and put back into a jar of water to keep them fresh. Half-eaten apples are frozen for smoothies or applesauce making. The children enjoy feeding their apple cores to their new house rabbit.

All truly inedible food waste is composted, to be used on the lawn and a small kitchen garden. The secret to composting all food waste, including animal products, even bones? First, she stores the scraps in the freezer. When there is enough (about once a month), the collection is defrosted and placed in a bokashi compost bin where it is fermented, then added to the garden. Bonus: this leaves the Hitchens’ trash “clean” and easy to transport. No curb-side waste removal service or pickup truck needed.

No surprise, perhaps, her zero waste aesthetic extends beyond the kitchen. Everything from toothbrushes to toys are likely to be made of wood or other organic materials. And, of course, she loves giving zero waste decorating advice to her clients at work.

“If people ask me…I encourage them to choose natural fibers, organic textures. They are healthy, naturally beautiful, and work with the Vineyard aesthetic. They help with air quality and off-gassing. My same rules apply to décor: how and where was it made? How long will it last? What will happen to it when you’re done? Small actions matter and can have exponential effects.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)