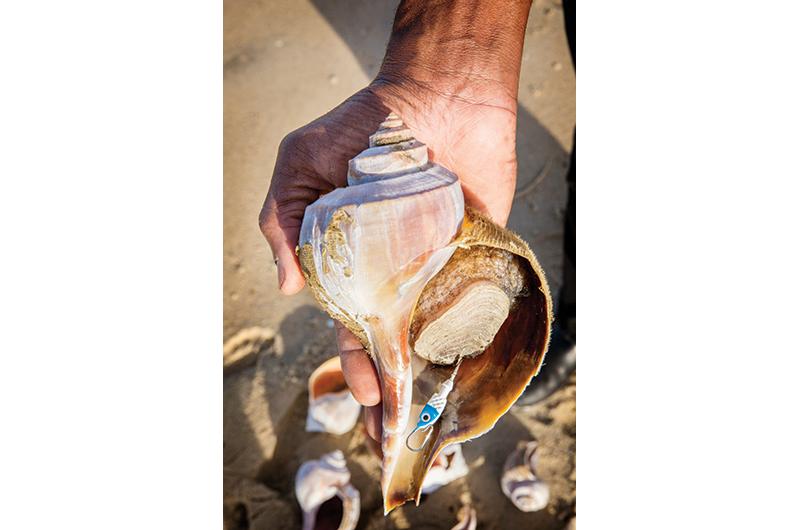

As a child, back in the days when the Inkwell was still an insider locution and not a T-shirt proclamation, I would occasionally happen upon a spiral shell that when held up to an ear seemed to echo the water’s roar. All too often it was broken or incomplete, but it was always intriguing; indeed, a complete one was a rare treasure. I called them conchs.

Many years later I would cross paths with similar shells, this time in Nassau in the Bahamas where I learned more about the marine gastropod mollusks. The Caribbean shells were from the queen conch, and while akin to the ones I’d found on Vineyard beaches in my youth, they are actually distant relatives. The local ones, it turns out, are whelks. With the queen conch listed as an endangered species, however, high demand for the meat spawned a Vineyard “conch” fishery for the whelks that appeared in a 2011 article in this magazine by Rebecca Busselle.

Conchs are used internationally in a variety of ways: culinarily, musically, and ritually. With some trepidation, given a shellfish allergy, I was persuaded in the Bahamas to try some in the days before the mollusk became endangered. Several men were engaged daily in preparing conch for tourists and locals alike, though given the mollusk’s reputation as an aphrodisiac a majority of the customers were local men. I watched as they carefully extracted the large, unattractive snail-like creature from its shell through a hole. (This allowed the shell to be sold as a souvenir, doubling the profits!) There was pounding, mincing, adding hot chilis, lime juice, and a dash of “secret” ingredients, depending on the individual’s recipe.

Over the years, I’d learn that the conch is so much a part of Caribbean history that there is an entire repertoire of regional conch recipes and lore. The distinctive honk when the shell is blown is a part of the traditional Bahamian winter festival known as Junkanoo. The shell horn, called lambi in Haiti, may have been used to signal forces during the Haitian Revolution. And a Port-au-Prince suburb that is named for the mollusk housed a hopping open-air nightclub in the Baby Doc era. In Jamaica, meanwhile, a conch horn is blown by islanders as an alarm. Conch pearls are rare and appear in finely wrought jewelry throughout the region.

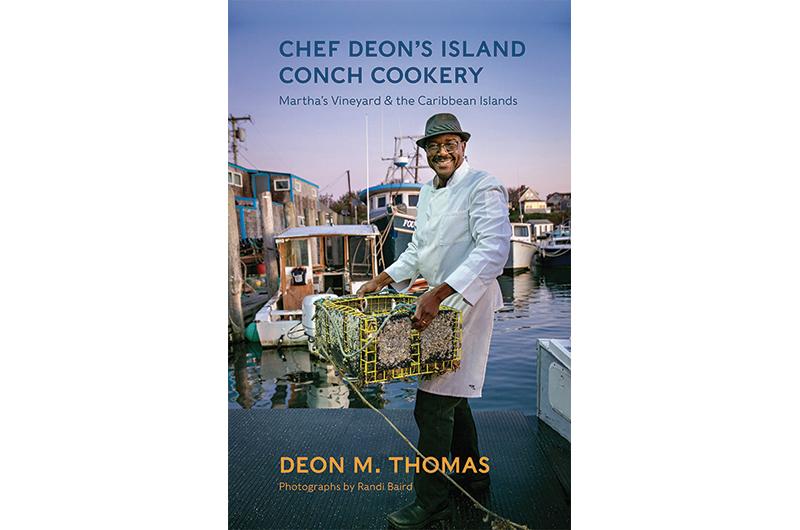

Imagine my surprise when years later, back on the Vineyard, I heard that chef Deon Thomas was serving conch at The Cornerway Restaurant in Chilmark. A Jamaican by birth, Chef Deon, as he is known, made the connection between the Caribbean queen conch of his birth and the similar mollusks on the Vineyard, his adopted island. Having built a clientele that loved his various conch dishes, he turned to using the local varieties when the depleted status of the queen conch made importing the meat impossible.

At first, even his crew of cooks were incredulous: “They took to berating the local fishermen in absentia for trapping the baby ‘conchs,’ as this would be a crime back in their island home of Anguilla,” he writes in his new cookbook Chef Deon’s Island Conch Cookery (self-published).

“I explained to my team the differences between the two gastropod species,” he continues. “Queen conchs (Strombus gigas) are herbivores; they are much bigger and found in tropical waters. Channeled whelks (Busycotypus canaliculatus) and knobbed whelks (Busycon carica), locally called smoothies and knobbys, are predatory marine gastropods that prey on bivalves (scallops, oysters, mussels and clams). These whelks, indigenous to the Atlantic Coast from New England down to Florida, are much smaller than queen conchs and are not dived for, but caught in baited traps.”

Chef Deon’s familiarity with all three species, as well as his culinary ingenuity, has allowed him to adapt Caribbean methods and recipes to the Vineyard product. In the book, he presents a range of preparations, from traditional ones like conch water, the allegedly aphrodisiac broth that has begun many a Caribbean Saturday night ramble, to innovative novelties like a conch cocktail with passion fruit marinade, to New England–inspired ones like Martha’s Vineyard conch chowder with cornmeal spinners. In addition to the recipes he explains the taxonomy and history of the mollusk, gives instruction on how to prepare it, and offers personal glimpses into his world on his islands north and south.

At first approach Chef Deon’s Island Conch Cookery may appear to be a slim tome, but it is full of wisdom, anecdotes, Island lore, and more. Once you crack its covers, you’ll never think the same way about those spiral shells you may find on the beach.

Shell Business

Adapted from Chef Deon’s Island Conch Cookery.

Though northern channeled whelks, also known as local conchs, are not typically stocked at Island fish markets, most of them are happy to procure some live whelks for a customer who requests it. To get the perfect yield, I freeze the conchs for a minimum of forty-eight hours before usage. I do not recommend crushing the shells to extract the whelks, as it can be a danger to someone not familiar with the process. After thawing, I use an oyster knife and gently tug at the meat to break the muscle and free it from its shell housing; with a counterclockwise pull it comes out with its stomach and viscera attached. Likewise for conch salad, cocktail, or ceviche, freezing is ideal.

The operculum (horny foot) is the hard covering at the tip of the conch foot muscle. The creature uses this part to get around on the ocean floor and to protect itself from predators when it retracts its body into its housing. I use the operculum to scrape clean the discolored outer skin of the conch foot. The horny foot comes off easily by applying pressure with your thumb and first finger. Once the conch is thawed and free from its shell, I remove the stomach and viscera. Then, gently rubbing the conch meat with my fingers or scraping by using the horny foot to remove the black skin spots and smelly mud, the white flesh reveals itself.

Cleaning this way eliminates the need to cook outdoors, which was necessary when people used to boil the whelk in their shell, mud and all, to remove the meat. The clean conch may be poached, thinly sliced, chopped, or tenderized with a mallet and finished by cooking in a stew.

The following recipes were originally published along with this article:

Buttermilk Deep-Fried Cracked Conch & Pepper

Conch Cake with Root Ginger Scalion Pesto

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)