Some people collect antiques. Some collect vintage cars or paintings. And there are some who collect seeds. But the seeds aren’t what Thalia Scanlan, a West Tisbury resident and one such seed collector, values as much as the fruit: tomatoes, with histories and names like the ‘Earl of Edgecombe’.

She explains that this one is named for the Earl of Edgecombe, who was a sheep farmer in New Zealand who went to England to claim his earldom and took with him the seeds of a tomato he’d developed. She holds out the glowing orange-colored results.

“It’s so beautiful and terrific,” she says about the Earl’s tomato, also described by others as rich, sweet, and tart all at one time.

“Let me introduce you to ‘Opalka’.” She pulls another tomato from its vine, this time a red Roma-type, originating in Poland. “This is a terrific-tasting tomato. I have five of these, because I like them for sauces. I’d recommend it for anyone who cooks – it just makes a wonderful sauce.”

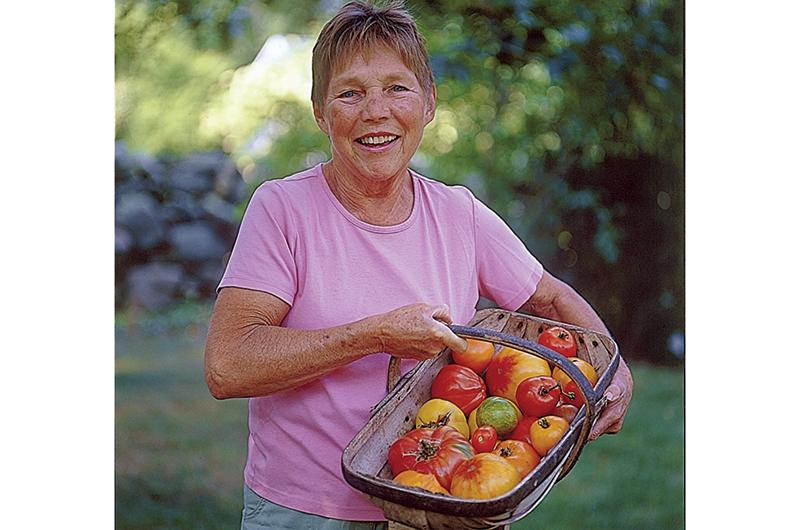

Welcome to Thalia’s garden – a slice of tomato heaven. Her collection, located in a seventy-square-foot garden plot in the backyard of her Lambert’s Cove home, includes eighty-five tomato plants with, at last count, forty-nine different tomato varieties. There are some other vegetables here – eggplant and peppers – but her interest clearly lies in the world of heirloom tomatoes, a world bigger than most of us would think.

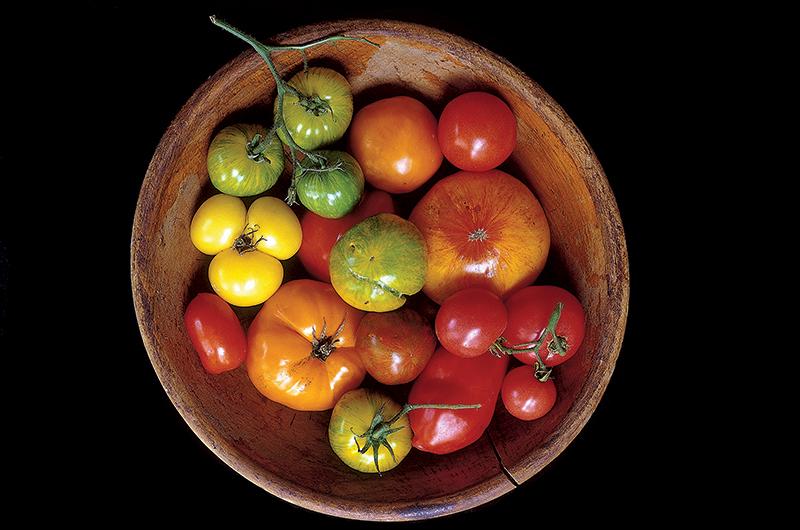

Held upright in cages, out here “in the jungle,” some of the tomato plants are taller than Thalia herself. She literally disappears and returns with sample after sample, some that are pink, green striped, mahogany, or simply a deep, deep red. The examples elicit lots of “wows,” some for the sheer size, one for its heart shape, and some for a jewel-like beauty, like ‘Big Rainbow’, with streaks of gold and red.

The flavors of Thalia’s tomatoes are spectacular as well. The taste of heirloom tomatoes is a prime reason why she and others grow them. Tomatoes can have up to thirty-one flavor components and, like wine, are described by growers with phrases like “intensely rich with sweet overtones” and “smoky and complex.” Nuances aside, they can be a welcome res-pite to today’s bland supermarket tomatoes – what Barbara Kingsolver described in her book Animal, Vegetable, Miracle as the “insipid vegetable-formerly-known-as-tomato.”

Heirloom tomatoes are just that, family heirlooms – grown from seeds saved over generations by families that grew or liked a particular tomato. They’re also now saved by gardeners like Thalia as well as seed companies (such as Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa) that act as clearinghouses, collecting these seeds from around the world to preserve biodiversity. “The whole principle is to have a seed bank of healthy, tried-and-true varieties of anything, including flowers and veggies of all sorts,” Thalia explains. “If something happens to a particular variety, we have healthy, productive seed to return to.”

Thalia’s tomato collection comes from a variety of sources, including European and American heirloom seed companies, other growers she shares with, and her travels abroad. She saves the seeds throughout the season from the best specimens and grows seedlings the next spring in her small greenhouse.

Some of Thalia’s most interesting tomatoes result from seeds she brings home from travels. She points to one row grown from “seeds that I, uh, smuggled from Greece last year.” Thalia was interested in the famous Greek ‘Santorini’ tomatoes known for their incredibly intense flavor. However, when she grew them on Martha’s Vineyard, she was a bit disappointed in the taste.

“If you’ve been to Santorini, it’s a volcanic island, and the soil is completely different,” she explains. “This is an interesting point. Because you grow it in your soil, in your environment, in your sun, it takes on an individualized flavor.”

Thalia’s own interest in tomatoes began early in life and has kept growing. “My mother grew them; I’ve always had tomatoes. I just love them.”

She grew her first tomato from seed while living in Manhattan, where she and her husband, Jack, lived for twenty years and raised three daughters (now in their thirties). At the time they lived in the city, they also owned a camp in the Adirondacks on Indian Lake, where there was a short growing season. So Thalia bought seeds of an ‘Early Girl’ hybrid and grew seedlings on a bookshelf with a fluorescent light to help them germinate. “I grew it in the apartment, which is the height of insanity.”

From New York City, the family moved to New Jersey – the “garden state” – where Thalia gardened in a ten-by-twelve-foot plot, and later to Illinois and Ohio. They eventually purchased a 28-acre, 225-year-old former sheep farm in Washington, Pennsylvania, where Thalia tended her largest garden to date. “The soil was fabulous,” she says. “Two hundred years of sheep doing their business.”

It was in Pennsylvania that she decided to take her gardening interest to the next level and become a “master gardener” (to complement her “other” career in advertising). In 1996, she attended the Pennsylvania State University Master Gardener Program, which includes training in many phases of gardening; in return participants dedicate volunteer time to horticultural community projects.

She also discovered heirlooms while living in Pennsylvania. “It’s right next door to West Virginia, fifteen miles to the line. There are a lot of old-time farmers and gardeners saving seed there, so that’s how I got hooked.”

In 1999, the Scanlans decided to downscale and sell the farm after their youngest daughter had left for college. The couple moved to Martha’s Vineyard, where they had rented for one or two weeks for each of the previous eight years. They bought an idyllic piece of property here, with a view of James Pond and a stone wall running along a section of a good-sized yard where the tomato garden would eventually grow.

Thalia does not market her tomatoes anywhere (she eats a lot of them in the summer, gives many away, and cans quite a lot for winter months), but you can buy heirloom tomato seedlings each year that she and others grow at COMSOG (Community Solar Greenhouse), a center in Oak Bluffs that holds gardening workshops, sells plants, and offers gardening space. Thalia discovered COMSOG when she first moved here. It was November, and since she was not yet established in her home that was under renovation, she needed a spot to start her seeds. COMSOG fit the bill. She eventually became president of the organization. Around 2001, she suggested COMSOG sell heirloom tomato seedlings on Mother’s Day as a fundraiser. It was an immediate success and every plant sold out. The sale is now held annually and has expanded to include thirty-seven heirloom varie-ties – the largest selection of heirloom tomato seedlings offered on the Island, she notes.

“People stop me in the street and ask, ‘Are you going to have ‘Cherokee Purple’ again this year?’ They’ll call off names. It astonishes me that they remember and they start to come looking for them.” She says COMSOG tries to have a tomato plant for every need, whether it’s tomatoes that can grow in pots for those without much room, or early producers for summer residents. “I have a Czech variety that produces in fifty-eight days, which is amazing.”

“I hear people say they are the best tomatoes they’ve ever had,” says Barbara Peckham, a COMSOG volunteer and secretary of the organization. “It’s one of the most popular things we’ve had. I don’t know what we would do without Thalia; she’s very knowledgeable, especially about tomatoes, but about most of the vegetables we grow. She has a wonderful sense of humor – and she never gets rattled, no matter how busy things get.”

Thalia says she and other heirloom growers often get caught up in the lore or story of a particular tomato, in addition to its specific producing qualities or taste. “It’s really kind of fun,” she says.

One of her favorite stories describes a tomato developed by a man during the 1930s. “I love Charlie,” she says as she picks up a hefty example. “Feel the weight of it.”

The tomato’s namesake, Charlie, had a radiator repair business in the hills of West Virginia, where heavy trucks hauling coal or timber would be driven up steep grades and often blow their radiators. His shop was located at the bottom of one of those hills, and the drivers would just coast to his shop. As a sideline, he started to cross several varie-ties of big-seeded tomatoes with a German Johnson tomato until he developed the one he then sold for $1 a plant. With the proceeds from his sales, he was able to pay off his $6,000 mortgage in six years during the 1940s. His prize tomato became known as Radiator Charlie’s ‘Mortgage Lifter’.

“I always grow Charlie for sentimental reasons, but I also love the tomato,” says Thalia. “It’s fabulous on a plate. My god, it fills the whole plate.”

In the last decade, Thalia has witnessed a burgeoning interest in heirloom tomatoes. “I have been amazed at the growth and interest and marketability. Nobody had heard of it. There were people who grew and loved them, but it was certainly not something you’d find at a farmer’s market, and now it’s all the hot thing.” Thalia discovered a similar interest on the Island organizing Tantalizing Tomatoes, a program that offered an afternoon of heirloom tomato tasting. Her last of three programs, held in 2006 at the Polly Hill Arboretum, drew an overflowing crowd of more than two hundred people.

With this growth, Thalia has found some mixed results. “I find that stuff that is sold as heirlooms hasn’t been tended to appropriately; the flavor isn’t where it should be. People are just cranking them out to sell quickly, it’s sort of like popcorn.”

From its origins in Chile and Peru, the tomato was initially spread around the world by Spanish Conquistadores who came across tomatoes in cultivation in Mexico during the sixteenth century and carried seeds to the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia. Many of these early tomatoes were in yellow, orange, and red hues now associated with heirloom varieties, according to one of Thalia’s reference books on the subject, 100 Heirloom Tomatoes for the American Garden by Carolyn J. Male (Workman Publishing Company, 1999). To write this book, Male collected and grew more than twelve hundred heirloom varieties at her farm in upstate New York.

One of the early pioneers of growing tomatoes here in the United States was Thomas Jefferson, who imported his seeds from France. Later, as Europeans immigrated to America, they brought seeds from their homelands; some of those are among the heirloom varieties being catalogued today. By the 1800s, American seed companies were selling these seeds by the packet.

In recent times, however, commercial tomato growers have increasingly narrowed the tomato pool to a limited number of hybrid tomatoes, developed for insect resistance or a longer shelf life. Seeds from a hybrid tomato – a cross of two varieties – are not saved, because they won’t produce the same tomato when planted. Heirlooms are open- pollinated and their seeds will produce a plant identical to the plant from which it came. Gardeners and farmers who grow heirloom tomatoes tend to showcase the more than five thousand tomato varieties; they want to ensure these varieties are not lost, as much as they want to experience the wide variety of colors, shapes, and flavors available today.

Thalia grows several hybrid varie-ties, for which she almost apologizes. The sweet ‘Sungold’ cherry tomatoes, for example, come up a winner in many taste tests, she says. “I do grow a few hybrids to keep track with what’s going on and to compare them with some of the others.”

Asking Thalia which tomato in her garden is her favorite is like asking her which child she favors, she says. But she will say one that she loves is a versatile red-pear tomato grown from seeds originating from Italy that she received three years ago from a woman working at Donaroma’s Nursery and Landscape Services in Edgartown. Not knowing the exact source of the tomato, Thalia says, “I call it my Parma.” She’s since grown and sampled three or four other red-pear tomatoes (good for both eating and cooking) sourced from the company Seeds of Italy in Harrow, England, to compare them to her red-pear Parma, which she still likes best. “If I grow it out over a period of years, it may change slightly; that’s how people get their own varieties, their own varietal names.”

She gives me a taste, and the flavor is rich and luscious. A tomato sauce made from these tomatoes would taste heavenly, as would any dish.

Thalia holds up a pink tomato called the ‘Rose de Berne’, from Switzerland, that came from another prolific heirloom tomato grower on the Island: Caitlin Jones of Mermaid Farm in Chilmark, who last year grew sixty heirloom tomato plants on land she farms with husband Allen Healy. Says Caitlin, “I’ve got the collection mentality. They’re being lost and this is my small part to preserve them.” Caitlin sells her heirlooms at her farm’s self-serve stand (off Middle Road) and at the Saturday Farmer’s Market in West Tisbury.

This September, Thalia and Jack will be heading to Lake Garda in Northern Italy. Thalia is looking forward to some more tomato research in the surrounding farming valley renowned for its wine and olive oil. Her love of tomatoes has recently led her to sample and collect olive oils as well.

She laughs and calls her interest in heirlooms a form of insanity. Thalia says she tells her husband, “‘It’s cheaper than diamonds,’ and he says, ‘Are you kidding, how many rings would you like?’ I say, ‘Never mind.’”

Saving seeds

This is Thalia’s method for saving seeds from an heirloom tomato:

First, she chooses a good tomato specimen she wants to save. She cuts it open and squeezes the seeds and fleshy part surrounding them into a Ball glass jar with an equal part water, then covers it with plastic. (She keeps each tomato variety separate.) The seeds ferment, then foam, in approximately five days. “It gets stinky,” Thalia notes. “The fermentation process cleanses the seed and helps get rid of any bacterium.”

Next, she pours the foamy liquid off and slowly adds water, which helps to separate the seeds from the fleshy gel. She continues to add water until the water becomes clear and the seeds settle at the bottom. Then she pours off the water and tomato solids, leaving the seeds. Thalia puts the seeds into a sieve and runs cool water over them. She puts the clean seeds on a plastic or paper plate and lets them dry for a week or more, depending on the humidity.

The dried seeds can be put in an airtight container, labeled, and stored in the refrigerator. Tomato seeds are viable for up to five to seven years, depending on the variety, she notes. She plants one seed per seedling and plants for more seedlings than she needs, to account for any seeds that don’t end up growing into plants.

Good reading

Thalia recommends two reference books on heirloom tomatoes and vegetables:

Heirloom Vegetable Gardening: A Master Gardener’s Guide to Planting, Seed Saving, and Cultural History by William Woys Weaver (Henry Holt and Company, 1997). Covers tomatoes and other heirloom vegetables.

100 Heirloom Tomatoes for the American Garden by Carolyn J. Male (Workman Publishing Company, 1999). Describes 100 favorite heirlooms and how to grown them.