Bundled in orange survival suits against the mid-April wind, members of the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) right whale team were scanning Cape Cod Bay. The sun had broken through to the west after a day of clouds, and the three women shaded their eyes. There was no land in sight. To a layperson, every small wave looked like it could be the head of a grazing whale. Every ripple suggested a flipper.

A North Atlantic right whale had been seen straight ahead but had disappeared. “How long’s it been since we first saw him?” research associate Christy Hudak asked. Eight minutes, someone responded. “Two more minutes and then we’ve got to move on,” Hudak said.

Someone else looked toward the stern and there he was, feeding on copepods a few yards behind where the research vessel Shearwater was idling.

“Son of a gun, he was behind us the whole time,” said Hudak as everyone turned to look at the grazing whale, just the top of his calloused black head visible. “You trickster!” intern Lauren Goodwin said. “Keep skimming!” Lauri Leach, another intern, pleaded as she took pictures for identification.

Right whale No. 1227, a male called Sliver who was first seen as a juvenile back in 1981, had been successfully documented as one of 249 North Atlantic right whales to visit Cape Cod Bay during the 2018 season. This is more than half the entire population of one of the most critically endangered marine mammals in the world.

People have looked for whales in New England waters for hundreds of years: to hunt them, to see them, and, like the team on the Shearwater, to try to save them. CCS, which has been studying right whales in Cape Cod Bay for more than thirty years, is based in Provincetown, the small town at the tip of Cape Cod. The modern town was built in part by commercial whaling during the 1800s, and today whale watching is a key part of the tourist economy.

Right whales have long been in trouble, their population severely depleted by the hunt and slow to come back. Endangered species recovery is a matter of math: births need to outnumber deaths. And in 2017 the equation for right whales took an alarming turn that made headlines: seventeen whales found dead in the United States and Canada.

The following year didn’t start out any better. A ten-year-old female right whale, a frequent visitor to Cape Cod Bay, was found dead off the coast of Virginia in mid-January. (While the number of deaths may appear to be down compared with the previous year – it remains at a single whale as of press time – experts point out that of the seventeen whales found dead in 2017, only one was reported before June 7.)

Worse, the winter calving season came to a close without a single right whale calf sighting, another unprecedented piece of bad news. Right whale researchers started to talk about extinction. If things continue on the current trend, scientists said last fall, North Atlantic right whales could be extinct in the next twenty-five years.

“It’s very unsettling,” Dr. Charles “Stormy” Mayo III, co-founder and leader of the right whale ecology program at CCS, said this spring. Mayo, the go-to right whale expert on Cape Cod, started field work at sea in 1984 and began aerial surveys in 1998, researching what he calls the “life and lifestyle” of North Atlantic right whales.

“I think the future right now looks a little grim, to tell you the truth,” he said. “It appears they’ve been in a decline since 2010. And there’s always hope that we’re just in a bad period, and maybe a cycle; maybe we’re seeing low numbers now, and give us a few years and there will be more calves. But right now it’s very disquieting. I never used to use the term extinct, and I think now we can at least offer the possibility that the population could go extinct if we do not find a way

to intervene.”

The path forward involves trying to reconcile two major parts of New England’s ecology and economy: whales and the lobster industry. Gear entanglements have been identified as a main threat to right whales along the eastern coast. While food, environmental changes, or other factors might contribute to the problem, scientists say, human actions can more easily change. Fishing areas can be closed, speed limits enforced, and whale-friendly lobster gear developed.

And it seems a reckoning is coming, whether the catalyst is right whales or not.

Humans have made it clear that whales are valued, including protecting them through legislation like the Marine Mammal Protection Act, said Sean Hayes, protected species branch chief at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NFSC) in Woods Hole. Lines have to be drawn when charismatic endangered species come in conflict with another resource we value, he said.

“In this instance it’s commercial fishing for lobster, a highly prized crop….We keep growing and expanding our resource consumption and they almost are a check on ourselves.”

“I think all of us have to recognize that we’re really all working for the same thing, for our own good,” Mayo said. “And that is to make sure no more right whales die, or as few as possible, because such a rare animal as a dead right whale caught in fishing gear is really a problem not only for the whales, but for a fishermen. A right whale killed by a boat is a problem for the industry that uses the boat. None of us can afford to have more right whales die.”

Protecting them, he said, “ultimately protects us.”

The North Atlantic right whale is the state mammal of Massachusetts. Adults are fifty to sixty feet long and weigh as much as eighty tons. They have black skin, no dorsal fin, and twin blowholes that look a bit like a horse’s snout. Their heads are often covered by rough white patches of calcified skin called callosities. These patterns are unique to each whale and allow researchers to tell them apart; the New England Aquarium manages a right whale catalogue of the entire known population.

The whales have long, downturned mouths and eat by grazing through the water, filtering plankton through eight-foot sheets of baleen. Their Latin name is Eubalaena glacialis, meaning true whale of the ice. Their common name, on the other hand, comes from being considered the right whale to hunt.

Because they are slow, feed near the surface and often close to shore, and tend to float after they die, they were the earliest and easiest whales to be hunted extensively by New Englanders. Like sperm whales, humpbacks, and other whales native to New England waters, right whales were hunted to dangerously low levels by whalers during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Before the invention of kerosene and other petroleum-based products, the oil rendered from whales’ thick insulating layers of blubber was used in lamps and candle making, as well as for lubricating the increasingly complicated machinery of the Industrial Revolution. The plastic-like rows of baleen from their jaws, meanwhile, were prized for use when flexibility and strength were important, such as buggy whips and corset stays.

Most commercial whaling tapered off in the early twentieth century with the rise of petroleum and the collapse of global whale populations – though it wasn’t officially banned in most countries until 1986. The hunting of right whales, specifically, has been illegal since 1935, when the League of Nations passed a resolution.

With protection, many global whale populations started to rebound. Most populations of humpback whales were recently taken off the endangered species list, with about 80,000 of that species in existence. Sperm and blue whales are still federally listed as endangered species, but their numbers range from tens to hundreds of thousands. Yet the North Atlantic right whale has lagged behind. In 1992 the North Atlantic right whale population was estimated at just 295 whales. That climbed over the next twenty years to about 500, leading to optimism that the trend was moving in the right direction. But starting around 2010 the recent decline began: last year an estimated 450 animals were alive.

According to Peter Corkeron, an Australian who has led the large whale program at the NFSC since 2011, the effects of whaling are still playing out. Joining Hayes in his office in Woods Hole, a papier-mâché right whale created by an intern on the table behind him, Corkeron explained that the rate of reproduction for rights is slower than other whales: humpbacks tend to increase at a rate of 10 percent per year, while right whales increase at 6 to 7 percent when all goes well. “So inherently they can’t come back as fast,” he said.

Further complicating things are right whales’ territorial habits. “They’re very coastal. Inshore animals are more likely to encounter things that we’re doing. They feed on the surface.”

In other words, Corkeron joked, “they kind of planned it out really badly.”

Globally there are three species of right whales, and while all were decimated by whaling, their divergent fates since the commercial hunt ended show both the legacy of whale hunting and the continuing role humans play in the story. The Pacific right whale, found in the North Pacific off Alaska, Canada, Japan, and Russia, is in even more dire straits than the North Atlantic right whale, in part because it was further depleted by Soviet whaling that continued through the 1960s. Scientists on the West Coast are struggling to rescue the Pacific whales, said Hayes, but with considerably less funding.

On the other hand the third species, the Southern right whale, is doing well in its habitat in the southern hemisphere, off Australia, South America, South Africa, and in Antarctic waters. The Southern right whales are similar to their northern relatives; in parts of Australia, Corkeron said, they linger so close to shore that you can camp on the beach and go to sleep listening to right whales blowing just thirty yards away. But their populations are growing. At the Head of the Bight, a main calving area “in the middle of nowhere” off the southern coast of Australia, Corkeron said, eighty right whales gave birth last year. The population is spilling down the coast, toward an abandoned whaling camp from where Australians once left to hunt whales.

The difference, said Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) senior scientist Michael Moore, is how humans are using the ocean. In his studies of human and whale interactions, he found that in the south “there’s far less shipping and fixed gear for traps, especially in Antarctica, than there is in the Northern Hemisphere.” North Atlantic right whales have “major problems because of the urbanization and industrialization of their waters, and therein lies the problem the Southern right whale doesn’t have.”

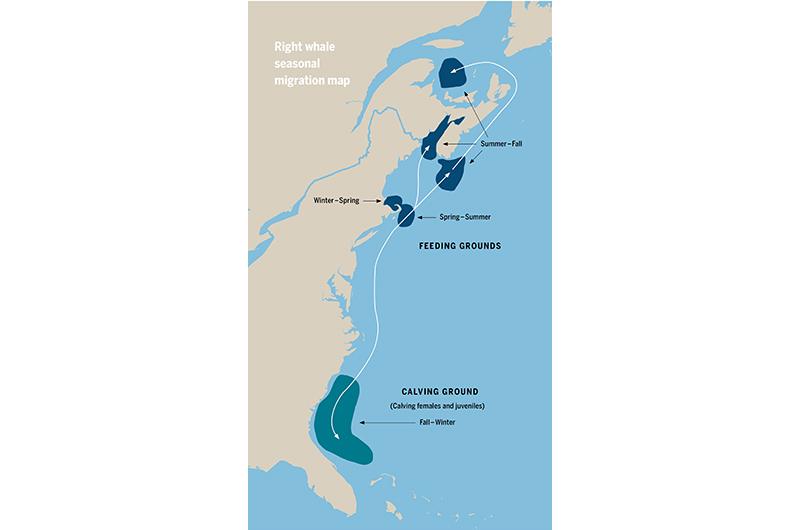

North Atlantic right whales migrate up and down the East Coast of the United States and Canada. They spend the late winter and early spring feeding in Cape Cod Bay and around the Cape and Islands, arriving as early as January and departing by May. The whales then follow their food north, traditionally to the Bay of Fundy in Canada. More recently, whales have been discovered in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence farther north, an area with heavy fishing activity. With the arrival of fall, female whales and some juveniles travel south, where calves are born off Georgia and Florida. Males and non-calving females don’t make the southern migration, but scientists aren’t sure where they spend their winters.

Throughout the range, researchers say, the whales are threatened by fixed gear from the lobster industry and snow crab harvest. Fishermen attach ropes from traps at the bottom of the ocean to a buoy above, so they can find their trap at a later time and have something to grab onto. Those vertical lines in the water, say scientists, are the main threat to whales. A secondary concern is ground line, or the rope that connects a string of cages. Hayes said a back-of-the-envelope calculation shows there are at least a million vertical fishing lines in the water along the eastern seaboard from Georgia to Nova Scotia.

“Their entire range,” he said. “Some areas are denser than others, but there’s no place, there’s no haven, and they have to swim through all that to carry out their life history.”

Scientists say about 85 percent of right whales have entanglement scars. Entanglement also takes a toll on whales that aren’t killed immediately. “Those that don’t die suffer from the drag and other stresses during the period of entanglement,” Moore said. And female whales need to be in robust health to bear calves.

By the end of 2017, the right whale death toll was striking. Twelve whales were found dead in Canada and another five in the United States, including three found on or near the Vineyard: one on Chappaquiddick, another in the opening of Edgartown Great Pond, and one on Nashawena Island. Another five whales in Canada were saved from entanglement in fishing gear. Hayes and Corkeron said the high level of Canadian mortalities might have resulted, in part, from whales moving into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, an area heavily used for the snow crab and lobster fishery that was previously unregulated for whale activity. For the first time last year, Corkeron sent NFSC’s aerial team up to survey the area, so it’s also possible the high number of dead whales were found because people were looking for the first time.

Population models had long accounted for a declining population, “but there was a missing body count, so to speak,” Hayes said.

It should be pointed out that entanglement in trap lines are not the only human-caused deaths of right whales. Of the twelve whales found dead in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, necropsies were conducted on seven. Five of the whales had signs of acute blunt force trauma, indicating a boat strike. One had “acute internal hemorrhage compatible with blunt trauma”; another had a skull fracture.

As bad as that sounds, it may not tell the full story. Scientists say that entanglement deaths are often gruesome and slow as a whale drags around heavy gear, burning extra calories. The rope eventually cuts through the skin down to the bone, sometimes wrapping around appendages and causing partial amputations, said Moore, who performed necropsies on whales for years.

“You rapidly get over the physical side,” Moore said of working with dead behemoths. “What never leaves you is the impact that it has on the animals from an animal welfare point of view.”

The effort to save the right whales from extinction is being fought on several fronts. There are some seasonal closures to boat traffic in areas like Cape Cod Bay when whales are there, and the U.S. Coast Guard announces vessel speed reduction zones whenever whales are detected feeding or transiting through inshore waters. Cape Cod Bay is also subject to trap gear closures to protect the whales, and this year the Canadian government has enacted closures as well. Better known to the general public, as they turn up in the news, are the efforts by trained teams to disentangle living whales when they are found. While this undoubtedly raises awareness of the problem and may help individual whales, it’s also a costly option that only helps one whale at a time. “It’s a treatment,” said Moore, “not a cure for the problem.”

Efforts are also focused on the way fishermen access their gear. Scientists say one solution might include weaker rope, to make it easier for whales to break free. And so-called rope-less technology, being developed by researchers at WHOI and elsewhere, is in the works. These systems aim to use acoustic technology as the means of communication between fishermen and their underwater traps, getting rid of the ropes that bedevil the whales. For example, a device on a fishing boat could communicate with a matching device on the fishing gear, releasing a spooled rope for the fisherman to grab.

It’s an expensive proposition, however, and Moore believes it will require government investment and support for fishermen if it’s to have a chance of being adopted in time to make a difference.

In early June several U.S. senators introduced the Scientific Assistance for Very Endangered North Atlantic Right Whales Act of 2018, or the SAVE Right Whales Act, legislation that would create a grant program for states, non-governmental organizations, and the fishing and shipping industries to work together to reduce impacts on right whales. The Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance has endorsed the bill, noting that cooperation with fishermen would be a priority for funding.

While that bill works through Congress, scientists are also focusing on factors like public awareness. “The idea of ethical conservation – if that becomes a priority then the seafood consumer, like wanting to know where your salmon is from, you want to know whether lobsters were caught in a whale-friendly way,” Moore said. “There’s going to be a premium to pay, a premium to have whale-friendly lobster.

“The rub is that unlike terrestrial industries, it’s out of sight, out of mind,” he said. “You aren’t thinking about whether or not a right whale swam by that trap and got entangled.”

The unthinkable question is increasingly being asked: is there enough time to save the North Atlantic right whale? On the Vineyard in the early 1900s, conservationists were focused on saving the heath hen, the grouselike bird with a distinctive mating dance that by then existed solely in the Vineyard’s sandplain grasslands. The state forest was established as a heath hen habitat, hunting was banned, predators eliminated. But the heath hen was in a so-called extinction vortex, with too few animals and too little genetic diversity for the species to survive. By 1928 there was one left, a male named Booming Ben, who returned, heartbreakingly, to the breeding grounds to utter an unanswered mating call. He was last seen in 1932 and the species was declared extinct.

Other stories have played out more recently: the last of the white rhinoceroses is being monitored in Kenya. The black-footed ferret, the only ferret native to North America, dwindled to just eighteen individuals, all living in captivity. The species is now slowly making a comeback.

But for right whales, large ocean-dwelling animals with life cycles tied to eating millions of tiny organisms, conservation options are limited. The species that offers the most analogous cautionary lessons, Hayes and Corkeron said, might be the vaquita (“little cow”), a small porpoise that lives in the northern Gulf of California. It is one of the most endangered marine mammals on earth, largely because of entanglement in gill nets. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the vaquita’s population was estimated at 567 animals in 1997 and 245 in 2008. Today there are less than 30.

“At that point, it will take a miracle to solve that,” Corkeron said.

“There’s a lot of different conditions, a lot of lessons learned,” Hayes added. He pointed to a top-down approach, like actor Leonardo DiCaprio reaching out to the president of Mexico to secure a commitment to save the vaquita. “One of the things repeatedly learned in conservation biology, you often have to fix these problems from the bottom-up,” he said. “The stakeholders are going to figure out how to save the right whale...it’s going to be the fishermen figuring out how to manage, harvest. With the vaquita there wasn’t engagement with the community on that.”

Captive breeding programs, like the ones used for the black-footed ferret, are usually last-ditch [efforts] and known as “condor time,” he said, a nod to the program to put the last California condors in captivity, breed them, and successfully reintroduce them to the wild.

Species respond unpredictably to those kinds of programs. Even if right whales could be confined to a safe area of ocean, which nobody has suggested is possible or a good idea, the vaquita offers another cautionary tale. A conservation attempt to put them in a managed enclosure went awry when the animals reacted poorly. A female vaquita died.

“The vaquita was a wake-up call for that,” Corkeron added. “They tried to catch them; it turns out that porpoises are very skittish and they just freaked out. It actually led to a really healthy conversation in the whale conservation world. You know, there are sort of inshore whales that you could keep, you probably could captive breed and save, and well, the question becomes, ‘Is that something that’s tolerable, and how?’

“What are you going to do, block off here?” he said, gesturing out the window to Vineyard Sound.

“You can feed dolphin fish out of a bucket,” Hayes pointed out. “You can’t feed Calanus to a whale.”

“It’s not an option, so we’ve just got to save them,” Corkeron said.

Down all the roads of the right whale future, one of them leads to the possibility that one day none will be left. It’s not clear what that would mean for the ocean. Whales contribute to the ocean ecosystem: they eat food, and they put nutrients back into the water. Whale poop, high in iron, has been studied as an ecosystem engineer. Whale placentas contribute nutrients and energy to the ocean – great white sharks hang around humpback whale birthing areas off Australia not to get at the baby whales, but to eat the placentas. And dead whales, too, eventually fall to the bottom and provide nutrients for an entirely different ecosystem.

At such low numbers, right whales have basically already been removed from the environment, Corkeron said, so the issue might be what is missing already that right whales once provided. Here in New England, “we don’t really know what it could have been,” he said. But like the vaquita, the right whale’s plight is a warning for other species.

“We could lose in this effort to recover right whales,” Hayes said. “Even if we do that the challenges for the fishery aren’t over. The story is on right whales right now, but the reality is there are just as many or more entanglements happening with humpback whales and minkes. And it’s not like if right whales are gone that it will just be, ‘Game on, fish however you want.’ We’re still going to have to manage to protect those species unless we just want to give up on them, too.”

Not that anyone is suggesting surrender. “They’re not at the point of no return,” Moore said. “There’ve been half as many forty years ago; they have the potential to recover. We need to let them do that. We have to back off, especially on the fishing gear. Vessel strikes as well.”

Back on board the Shearwater on Cape Cod Bay that day in mid-April the right whale team recorded three right whales and collected plankton and water samples. As the boat started to head back toward Provincetown, research associate Hudak sounded a note of optimism.

“The whales we’ve been seeing are robust,” she said. “That gives us hope. The last couple years, they’ve been lean. Not really healthy. This year they’re starting to look really healthy.”

Coming back around Race Point, the sun setting behind the lighthouse and a thick line of cormorants standing sentry along the jetty, it was hard not to think about whaling ships sailing out of Provincetown, lobster fishermen hauling up traps and selling their catch up and down the Cape, whale watchers boarding a boat to try to get a glimpse of the leviathan, the idea of drifting off to sleep listening to right whales blow offshore. It was hard not to wonder about a time when boats might leave Provincetown looking for right whales and never find one; what that would mean for the ocean, and for us.

Follow the Food

To figure out where right whales go, scientists follow their food: tiny cold-water copepods about the size of a grain of rice. Right whales mostly eat Calanus finmarchicus, which are high in protein, contain omega-3 fatty acids, and are most prevalent in the North Atlantic.

Dr. Charles “Stormy” Mayo III, leader of the right whale ecology program at the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS), estimates that a right whale feeding in Cape Cod Bay eats about 125 pounds of plankton in an hour, and may feed for eighteen hours a day.

Studying plankton is a key part of the CCS fieldwork on Cape Cod Bay. Once a whale has been seen feeding in an area, the right whale team gets to work dropping tow lines in the water to take samples of the right whale food.

On the April trip one of the researchers held a container of what looked like a watermelon slushie. The plankton even smells like watermelon, research associate Christy Hudak said. Samples are taken from different depths and the plankton preserved in small jars for analysis. Finding out more about what right whales eat, and where it is found, will help identify areas to monitor. “It’s pretty clear that these right whales are depending on the food to guide them to various places,” said Mayo.

Because of their right whale connection, Calanus finmarchius has been studied so much that scientists know the plankton “almost as well as the right whales do,” Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s Peter Corkeron quipped.