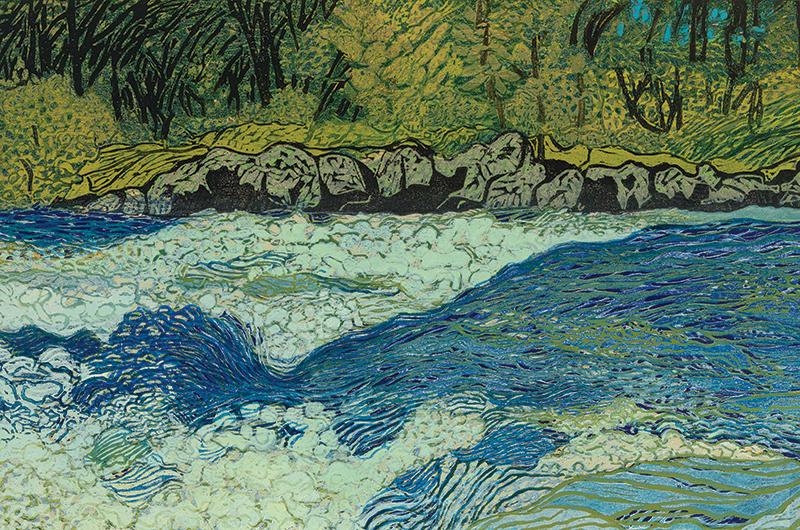

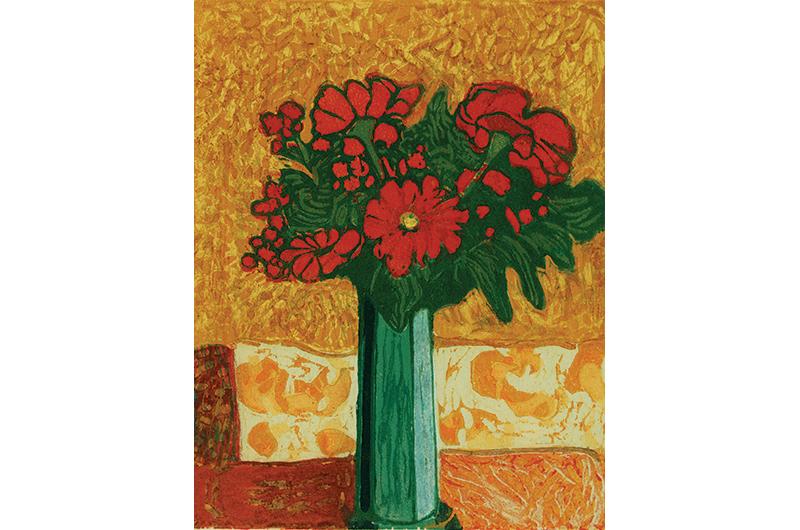

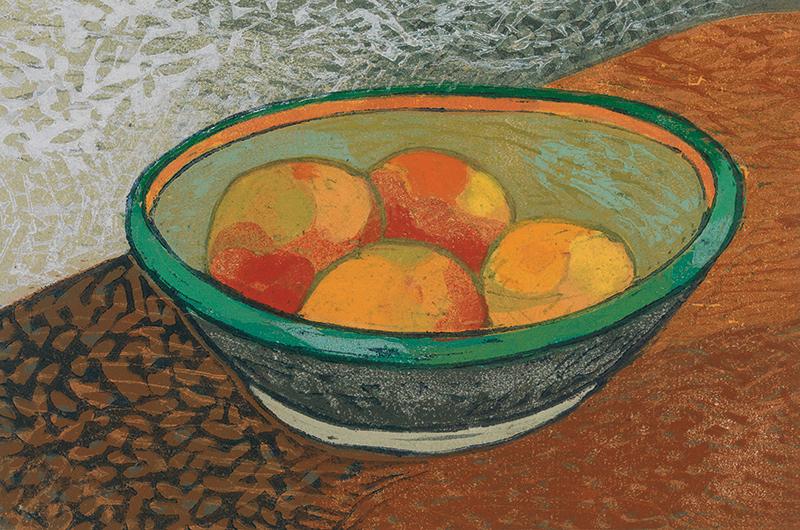

I begin with a drawing on tracing paper,” said Ruth Kirchmeier in her West Tisbury studio. The space is upstairs in what was once a goat shed, and the walls are lined with completed woodcuts from years and decades past. “The drawing is transferred to a block of wood – ideally basswood because it’s easy to cut. But I use fruitwood – apple or cherry – when I am carving something small like a portrait, because on fruitwood, a hardwood, I can get more detail,” she explained of the many steps required to make each work of art. “This first block I carve is called the master block. Using knives and gouges, I carve away the portion of the wood that I don’t want printed, leaving a raised drawing.

“Next, I roll ink on the finished carving and print it – usually on Japanese paper – using rollers and rubbing with a wooden spoon. While the ink on this master print is still wet, I transfer – again using the wooden spoon – the drawing on it to a new block of wood. Each color requires a separate block with unwanted details from the master block cut away. For example, if a barn is in the original drawing, and I want it to be the only red in the finished print, all except the barn is cut away on the block for that color. During the entire process the paper remains in place on a printing frame to ensure perfect registration of the successive colors and is brought down on each new block, printed, then lifted out of the way, clearing the decks for the next color.”

In other words, creation is a long process, incrementally achieved. It is meticulous, painstaking, often exasperating.

But then again, as Kirchmeier, who turned eighty-four this past December, will tell you, so is a full life. When she isn’t gouging wood for a woodcut or applying ink for a print, she is likely nurturing plants, baking a pie, or taking long woodland walks. And when she is doing none of those things, she revels in recounting the fully lived lives of her German-born parents, starting with the 1922 arrival in America of her mother, Theresia Birner.

Seventeen-year-old Theresia, a native of Bavaria, was invited to move to America and stay with her eldest sister and her husband, who had previously emigrated. But when she arrived at their Manhattan apartment without the singing canary from the old country that her brother in law had requested, he refused to let her move in. She tearfully explained that the bird had escaped on the steamer and was somewhere over the Atlantic, but to no avail. Turned away, and knowing no English, she quickly found a job as a live-in maid with a wealthy family on Park Avenue and set to learning English and acquiring friends.

“I think she was something of a libertine,” Kirchmeier said. “She had boyfriends aplenty and was thoroughly enjoying social life in New York. She loved to dance and party and have a thoroughly good time.” In her late twenties, she met Heinrich Kirchmeier, a fellow Bavarian with no escaped canary in his past, but whose arrival in America had also been interesting. A cabinetmaker by trade, he had left his small hometown and gone to Hamburg, where he lived in a commune for a time. When he tired of that he built himself a folding kayaklike boat and set off down the Danube River. By the time he got to Romania, he was long haired and bedraggled and was promptly thrown in jail.

Happily, though, he was as good with cards as he was with wood and talked his guards into a game. Once their money was in his pocket, he grandly suggested that they all go out on the town for a drink, and after a few he managed to give them the slip to head back to Germany. There he joined the merchant marine and set sail on a vessel bound for New Zealand, only the ship’s plans changed en route and it docked instead in Newark, New Jersey.

“My father liked what he saw of Newark through a porthole,” Kirchmeier recalled. “He didn’t want to return to Germany, so he jumped ship.” He quickly disposed of the wooden shoes all crew members had been issued to identify them as German merchant seamen and spent nights, for a while at least, hiding away in Penn Station. He eventually found a small, largely German-speaking rural community in the foothills of the Ramapo Mountains in northeastern New Jersey where he built himself a rustic camp. “A short time later, on a visit to New York with a German cabinetmaker friend,” Kirchmeier said, “he also found my mother to be.”

Theresia added this fellow Bavarian to the list of young men she was seeing, but in time it was clear he was different from the others. He was intellectual. He was artistic. He was charismatic. The first time he proposed, however, Kirchmeier’s mother wasn’t sure that she wanted to be married. By the time she was thirty-two she agreed, and they honeymooned on an old Indian motorcycle with a sidecar on which they went to Florida and camped for several months. When they returned (with a dog sharing the sidecar with Theresia) they moved into Heinrich’s camp. It was a simple structure of cinder blocks and wood, with an outdoor staircase to the bedrooms. There was no running water and an outhouse. It was there that Kirchmeier, who was born in 1935, and her three sisters and a brother grew up.

During the war years, refugees from Germany and Austria – many writers and artists among them – became frequent and inspiring visitors of the Kirchmeiers. “I remember how my sister and I had to give up our beds for them sometimes. There were important people among them. One was the German painter Josef Scharl; another was Oskar Maria Graf, a well-known Bavarian writer of that day. Growing up with such people around me, I felt as if I were among Olympians! And I wanted oh so badly to go to art school,” she remembered.

After high school, she took an exam to enter The Cooper Union art school in Manhattan but failed to get in. Her second choice was the Pratt Institute, also in New York, but which at that time trained its students largely for commercial art. It was fine art – like that of her parents’ friend Josef Scharl – that she wanted to do, and after two years at Pratt, she reapplied to Cooper Union and was accepted. Soon she was studying art history, architecture, painting, and the making of woodcuts.

“And it was woodcuts, I found out, that were what I really wanted to do.” At Cooper Union she also met her future husband, German-born Rolf Ohlhausen, who was a student of architecture. Before earning her own degree she went with him to Cambridge where she worked in advertising while he pursued his master’s at Harvard. Then to Portland, Oregon, where he taught at the University of Oregon. Periodically, she would try her hand at woodcuts, but knew she needed both more time and more training to succeed in doing them. After the couple returned to the East and settled in a Brooklyn brownstone, she was kept busy being a mother of two sons, Eli and Jacob. But she also turned one room in the house into a studio for her artwork, and finally managed to complete her degree at Cooper Union.

During those years the Brooklyn Botanic Garden was within walking distance of her home and she would visit it with artist friends for inspiration. She tried her hand at painting oils, “but I had known for a long time that my medium was the woodcut, and I taught myself how to do color ones. Sometimes,” she said, “there are as many as 100 colors in one of my woodcuts. The Japanese did woodcuts with many colors, after all.”

Among her New York friends were Selina Trieff and Bob Henry, who were well-known artists in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, at that time but had begun to summer on the Vineyard. They invited the Ohlhausens to visit them at Lambert’s Cove, where they were renting Lloyd Merry’s chicken coop. The Ohlhausens pitched a tent nearby, and Kirchmeier soon found herself enraptured by the Island. In ensuing summers, she and her family stayed at Highmark on Middle Road in Chilmark and at the Stein house, also in Chilmark. When they heard that the renovated goat shed behind Olga Bryant’s house on the Edgartown–West Tisbury Road in West Tisbury was for sale, they bought it and Rolf made additions to it.

In 1988, she and Rolf separated and Kirchmeier and her younger son, Jacob, moved year-round into their former summer dwelling. She had become good friends by then with her neighbor, Olga. Olga’s son, Nelson – hunter, fisherman, and writer of The New York Times’ Field and Stream column – kept an office at his mother’s for use when he was on the Island. He and Kirchmeier met and became companions, sharing the former goat shed for more than three decades until his death at the age of ninety-eight earlier this year.

Many of Kirchmeier’s woodcuts feature Island and New Hampshire ponds and woods she has explored with Bryant. Others are of flowers and family. Virtually every day she is in her studio at the top of the old goat shed – a setting not unlike the bedroom she reached by outdoor stairs when she was a child in New Jersey.

As the day ends, however, she is likely to be in the kitchen cutting apples and rhubarb for a pie, or roasting a loin of pork with cranberries and honey and garlic. On holidays, or if there are special guests, all may gather in the living/dining room. There they will sit below a portrait of Albert Einstein painted by Josef Scharl, who inspired Kirchmeier in her dedication to art.

The portrait hangs above the fireplace in a frame hand-carved by her father, Heinrich, and though she doesn’t think she chose wood as her medium because her father was a woodworker, she said, “when I am doing a woodcut today, I know I am still trying to please my father.”

Heinrich also fashioned the mantel below the painting out of an eighteenth-century hope chest brought long ago from his and Theresia’s Bavarian homeland. It seems to fit in perfectly with their daughter’s more recent woodcuts. In her art and her life, the old world and the new are, somehow, gracefully joined.

4 comments

4 comments

Comments (4)