At a time when it seems that everyone and their little sister has a conspiracy theory, not to mention during an ongoing global pandemic, a title like Bitten: The Secret

History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons might tempt you to  pass by with a smug shrug. But that would be a mistake, and not just for readers on tick-infested

islands such as ours. There is plenty of Cold War kookiness to keep pages turning – lone star ticks laced with radioactive material, strange bacteria with code names such as “the Swiss Agent” that mysteriously disappear from the research records just when they appear to be important, mild-mannered biologists who happen to have secret Swiss bank accounts.

pass by with a smug shrug. But that would be a mistake, and not just for readers on tick-infested

islands such as ours. There is plenty of Cold War kookiness to keep pages turning – lone star ticks laced with radioactive material, strange bacteria with code names such as “the Swiss Agent” that mysteriously disappear from the research records just when they appear to be important, mild-mannered biologists who happen to have secret Swiss bank accounts.

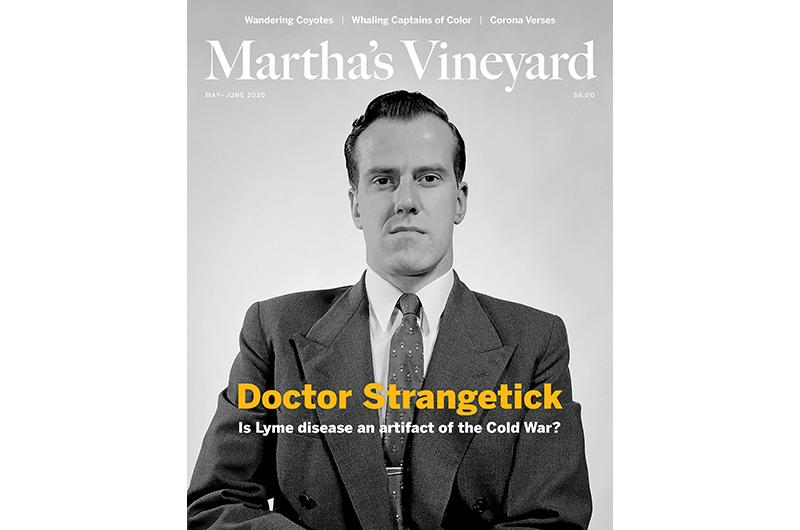

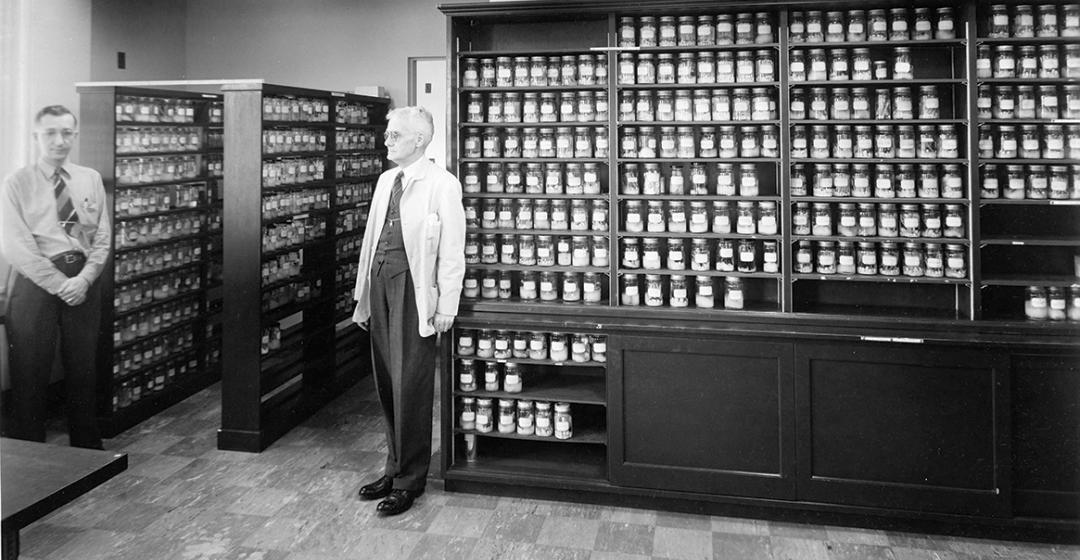

The book, which is coming out in paperback in June from Harper Wave, is essentially a biography of Wilhelm “Willy” Burgdorfer, a U.S. government biological weapons researcher. In the 1960s he developed methods of “weaponizing” ticks to carry various diseases and aided colleagues with experiments involving the release of thousands of lone star and other types of ticks into previously uninfested areas in order to study how fast they spread. He later discovered the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, which was named Borrelia burgdorferi in his honor, and late in life implied that he believed the Lyme epidemic was probably caused by a military experiment gone wrong.

It’s all meticulously documented by author Kris Newby, an award-winning science writer at Stanford University and documentary filmmaker. We caught up with her by telephone from California for the following edited conversation:

Martha’s Vineyard Magazine: Before we get started talking about your book and about tick-borne illnesses, it goes without saying that we hope you and your family are doing as well as can be expected given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. How are you faring?

Kris Newby: So far my family is doing well, but it’s challenging living under California’s draconian “shelter in place” rules. I do, however, appreciate having the time to think deeply about the flaws in our public health institutions that led to the runaway Lyme disease and COVID-19 epidemics. In both cases, we’ve fallen short of aggressively and accurately testing, such that we know where the diseases are spreading. Without this data, we can’t promptly diagnose, treat, and mitigate human disease.

MVM: Your own journey with tick-borne illnesses started during an ill-fated vacation here on the Vineyard, correct? You write about how difficult it was to get diagnosed in the book.

KN: It all started on Martha’s Vineyard in 2002. We were staying with my best friend in Chilmark, and we took a sailboat ride over to Nashawena, which is where I am fairly certain both my husband, Paul, and I were bitten. It took a year, ten doctors, and $60,000 to get diagnosed, because, really, the doctors in California aren’t familiar with tick-borne diseases.

About eight months into it we felt we were on our way to a death or worse than death. It was very serious, and we had Lyme disease and babesiosis. You know, I had to shut down my business, I could barely function, and we sort of had latchkey kids. We would feed our kids and then go to bed at about seven, and they were in middle school at the time and they would have to fend for themselves.

MVM: How are you and your family doing now?

KN: I feel like I’m fully recovered. The thing that finally kicked it was that it was hard for oral antibiotics to work, but I went on a course of intravenous antibiotics and that finally kicked it. And then my husband relapsed a couple times until he had an intravenous antibiotic and now he seems really good.

MVM: Is it your sense that had you been diagnosed earlier and put right on doxycycline, the way many are here, you might have had a different experience?

KN: I feel like for most people, if you got a normal course of antibiotics in the first month, I think you would never know the bullet that you dodged. You would go on and live a normal life and never think anything of it. I think the compounding factor with Lyme disease is that we don’t have a test that works in the first month. We haven’t given physicians license to treat based on clinical symptoms or travel history. The first eight doctors I went to, I said, “We just came back from Martha’s Vineyard. We both have the same symptoms. We got sick on the same day. We think we have Lyme disease – would you test for it?” The first eight doctors refused to test for it because they said it’s such a rare disease.

MVM: Before writing this book you were one of the principal producers of the 2008 documentary about Lyme disease Under Our Skin. So you’ve obviously been on the trail of tick-borne diseases for a long time. When did you first suspect that there might be more to the story than what you might call a “natural” course of tick transmission? What was the first clue that made you say, “Wait a minute.…”?

KN: It was during an interview with Willy Burgdorfer [a retired U.S. government researcher] in 2007 for the documentary. The director, Andy Wilson, and I were in Hamilton, Montana, setting up for the interview, and all of a sudden there’s a pounding on the door and it was a scientist from the lab who said, “I’ve been asked to sit in on this interview.” And Andy Wilson says, “No, Willy Burgdorfer discovered Lyme disease, he’s retired, he’s a private citizen, you cannot sit in on this interview.” So there was a very tense standoff.

I was very frightened. And then we did the interview and Willy told us things that we had never heard from a government official, which is that [the National Institutes of Health] knows that Lyme disease can be chronic and disabling, especially for young children with developing neurological systems. He said Lyme disease is a shameful affair because all the money goes to the same scientists who know the results of their experiments before they conduct them. So all that was pretty shocking, and then when we turned off the camera Willy Burgdorfer said, “I didn’t tell you everything.”

And we knew from the way the government wasn’t open about the disease in so many ways that something was up. But we’d been filming for three years at that point; we had to get the film out. And the rumors were always swirling about something getting out at Plum Island [the federal animal disease research facility in Long Island Sound]. But we finished the film, it did really well, and I was going to let that be and pass the torch to other activists. I got a really good job at Stanford as a science writer.

But then a documentary friend of mine sent me what was basically a confession tape from Willy Burgdorfer, saying he thought that the outbreak around Lyme, Connecticut, was caused by a bioweapon. That was the starting point for my book.

MVM: Willy Burgdorfer is the central player of the story, and if he could be explained in one or two sentences you wouldn’t have needed to write a book. But is he a tragic figure in your mind? Or is he evil? How would you describe him as a character?

KN: One thing that made me want to focus on him is that he’s very complicated, and, like everybody, he’s got a lot of gray area. Some people end up thinking he’s a bad guy, and some people end up thinking he’s a good guy. So, you know, he obviously started out idealistic. He was very excited to come to America [from Switzerland] and do research. He fell in love with Montana, which has soaring mountains on either side, a little bit like Switzerland without all the rules. He married a local girl. He loved his work. But then he slowly got sucked into the biological weapons program, which was really as big, almost, as the Manhattan Project [that developed the nuclear bomb].

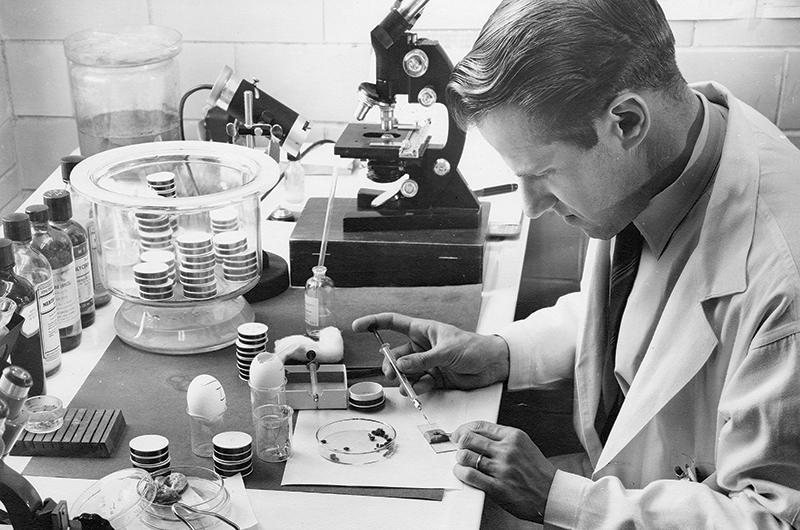

I think that the bioweapons program was very compartmentalized and most of the scientists who were working on it didn’t see the whole picture. But Willy decided to contract with Fort Detrick [in Frederick, Maryland], which was the headquarters of the bioweapons programs. So I think he had a wider view, and very soon after he got here he realized that he was working on weapons instead of researching and trying to cure insect-borne diseases. He was trying to make ticks into eight-legged soldiers, weaponizing them, so I think he for a while kept it compartmentalized.

He had a young family, he needed a job, he didn’t want to go back to Europe. But then toward the end of his life he was suffering from the disease that was named after him. I think he had more empathy toward the patients who were suffering, and he thought the epidemic was just really causing suffering of millions, so he had a change of heart at the end. Which is why he had left all these journals.

I think readers will have to make up their mind about what they think of him, but certainly he’s a very interesting character, and when I ran across the story I thought, “Well, this is the story of a lifetime. It doesn’t get more interesting than this.”

MVM: You imply in the book he may have been a double agent.

KN: He seemed to have had at the time of his death a lot of money, and none of his relatives knew about it until after he was dead. And as a public servant we have open access to his salary, and the amount of money he had at the time of his death considering he wasn’t a very sophisticated investor is suspicious. Also, after 9/11, he had had several visits from “men in black” from the government to question him about missing material and biological agents from his freezers.

And in the mid-1970s he had, you know, a lot of money pressures. He had two kids in college. He had a wife who had a lot of health problems. And he had a very low government salary. And then he was going to Europe a lot. He went to this one conference with a whole lot of people from behind the Iron Curtain, and all of a sudden he opened a Swiss bank account right after that and left the passbook in Switzerland. There was just a lot of suspicious behavior. And when he came back from that conference, he was buying new cars and doubling the size of his house with several additions. So.…

MVM: Do you think that was a part of why he didn’t want to give up the whole story? His “confession tape” is more of a nondenial than an outright admission, right?

KN: At no time when I was questioning him about biological weapons did he say, “Absolutely not, that’s outrageous.” He would detail some of his experiments. He said he was asked to put plague in fleas. He said he was asked to see if he could get ticks to reproduce faster so that they could be used as weapons of war. But in my discussions with him he was never 100 percent fully disclosing, so there was always something that was hidden there.

MVM: You do a great job of saying, “This is how far we can say we know, and you have to draw your own conclusions.”

KN: A lot of people have written off my book as conspiracy theory. I tried very hard to hinge everything on facts and documentation and eyewitness testimonies, and I think I was very careful about saying what we know and what we don’t know. But this isn’t that hard to believe if you look at this Fort Detrick division that did the tick-borne weapons. They also did the LSD experiments, the Manchurian candidate experiments, the Castro assassination plot. So it’s not that radical.

The last chapter I really make a call to action, because I went as far as I could go as a journalist. But to the scientists, I say that if what Willy said is true – that there is an organism related to the diseases that was a biological weapon – the scientists can genetically sequence that now and figure out where it came from.

And also, I’m sure it will pique the interests of investigators within the government to say, “Hey, we were really vulnerable here.” And they may drill down into Willy’s background. Certainly I tried very hard, but I wasn’t able to get any documentation on surveillance of Willy by the FBI or the state or the CIA. All those documents are buried deep.

MVM: Even if you don’t have the smoking gun of documents, what makes the way this cluster broke out look suspicious?

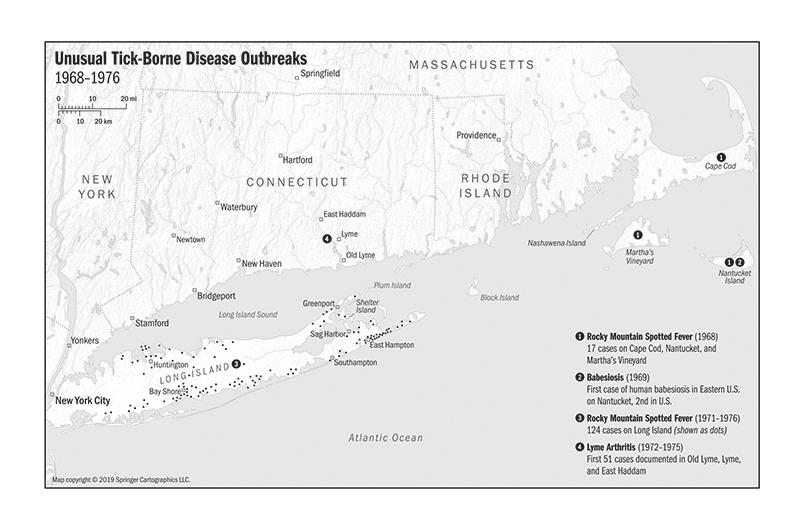

KN: The thing that was suspicious is that around 1968 three highly unusual tick-borne diseases suddenly appeared around the states surrounding Long Island Sound. So in ’68 you had the first cases of human babesiosis in the U.S. around Nantucket. In ’68 you had the first case of what seemed like Lyme arthritis in Connecticut. And during that time you also had this outbreak of a rickettsia, very close to Rocky Mountain spotted fever, but it didn’t test positive for spotted fever and it was fairly fatal. It put a lot of people in the hospital.

If you look at the documentation for when the government is looking for a suspicious outbreak, what you see is that there are eight guidelines for saying, “Hmm, is this unnatural or natural?” And it hit on almost all of those eight guidelines for unnatural. A lot of animals dying first. Then you have the sudden appearance of highly unusual diseases with high mortality, and that certainly was the case with babesiosis and spotted fever. Not so much Lyme.

And then it’s unusual that these three diseases appear that are all tick borne and they coincided with the government use of ticks as weapons and tick-borne disease. We know the government put dangerous germs in ticks and dropped them on Cuba for sure – we don’t know where else. There was a lot of open-air tests of those ticks too.

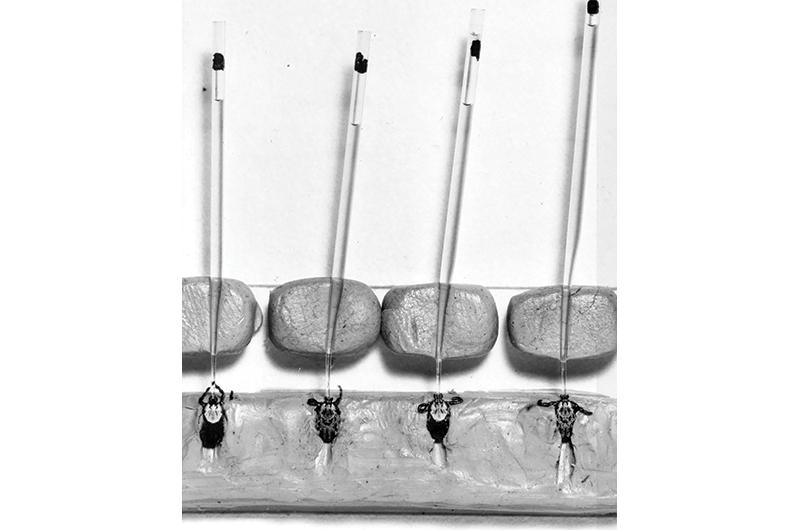

MVM: Those open-air tick drops you document in the book are almost as astounding as the images of Willy Burgdorfer force-feeding ticks with diseases!

KN: There was open-air release of hundreds of thousands of ticks around Norfolk, Virginia, and these ticks they made radioactive so they could trace their spread over years with Geiger counters. And the ticks that they released there, in part, were lone star ticks, which are very aggressive. And before those experiments lone stars were not really found above the Mason–Dixon Line. But shortly after those open-air experiments, those ticks showed up for the first time established on Long Island.

MVM: We on the Vineyard are unfortunately well aware of the arrival of lone star ticks. Is it your opinion that if they hadn’t released them, they wouldn’t be as far north as they are today?

KN: In my opinion, it’s highly likely. I talked to some experts, two experts in ticks, and when I told them about those open-air experiments, they were aghast. And they said, “No, they didn’t do that.” I said, “Yeah, they did.” They said, “You’d never be able to do that now.”

Obviously releasing hundreds of thousands of non-native ticks can move the dial on changing an ecosystem, and we are now seeing that lone stars are displacing the deer tick. And any time you release a non-native species in a new area, there’s going to be a disruption. The problem with the lone star is it’s super aggressive. They swarm. Unlike the deer tick, they have eyes they can use to stalk their prey. They also carry the rickettsia [Rocky Mountain spotted fever, etc. bacteria], which can be deadly. So in my opinion it’s had an environmental impact.

MVM: Those qualities of the lone star, they are presumably what the biological weapons people liked?

KN: Yeah, they were so aggressive, and they would spread more rapidly. And we have the complicating factors now all of a sudden. These lone stars are causing this red-meat allergy. Someone can be bitten by a lone star and something in their saliva triggers this red meat allergy that all these diseased people have for life. It can cause anaphylactic shock and disrupt lives in a major way.

MVM: In your opinion, what is the biggest problem regarding the current strategies toward treating these diseases?

KN: My takeaway is that we oversimplified the problem when Lyme was discovered in [1981] and we are not really, from the medical and scientific view, taking into account mixed tick-borne infections [having multiple infections, such as babesiosis or Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Lyme at the same time], which can be much more serious than Lyme infection alone.

I don’t think there is any one bad guy. I think what has made this tick-borne disease epidemic much worse are mostly incentives in our profit-driven medical system. So we know the cure for these tick-borne diseases is an early dose of antibiotics, but all those antibiotics are off patent, so there is no incentive for big pharma to develop an expensive new blockbuster drug. Pharma is often a force for good in curing new diseases, but they sort of ignore the tick-borne diseases.

Then we have the medical insurance companies. Denying that chronic Lyme exists helps their bottom line. They are more than happy to say chronic Lyme doesn’t exist because it’s truly expensive to treat, and if you say it isn’t a disease then you don’t have to pay for it.

Even if you take off the table that something might be bioweaponized, our medical institutions aren’t treating these seriously enough. We need to invest in rapid tests. We need to educate frontline medical people on the symptoms of mixed infections, which are very different than Lyme alone. And then we need to be more aggressive about treating up front, because if you let tick-borne diseases linger, they ruin lives, destroy families.

MVM: The need for tests brings us back around to the tragic and sad irony that we are having this conversation about the history of biological warfare and treating tick-borne disease in the context of the greatest pandemic in recent memory. How, if at all, has the current situation changed or informed the way you think about the story you tell so well in Bitten?

KN: I can’t help viewing the COVID-19 situation through the lens of the history of biological weapons. While this viral strain was probably caused by a random genetic mutation, it’s possible that some scientist was manipulating this bat virus genome and it escaped from the lab. History shows us that if humans are exposed to a completely new virulent pathogen, lots of people will die before the population develops “herd immunity.” My book is really a cautionary tale on what happens when we mess with nature without carefully considering unintended consequences. It’s also a reminder that humans aren’t really at the top of the food chain – microbes and bugs have had a lot more time to develop survival strategies.

It’s a wake-up call for our species.

19 comments

19 comments

Comments (19)