Imagine entering a Race Machine. Once inside, it is assumed by nearly everyone, year-rounder to summer resident, that you are visiting your second home. By default, ownership of a second home implies a reasonable level of financial success. People speak to you as a perceived equal, do not racially profile you in stores or restaurants, and no one assumes you are poor or uneducated because said qualities are associated with Brown skin. Almost every summer I go inside this machine, as do so many other Black visitors once they step foot on a ferry to the Island.

At least, that’s how I explain it to those who haven’t been to the Vineyard before, who wonder what’s so special about the Island and why it’s become something of a safe haven from the mindset of an increasingly polarized mainland U.S.

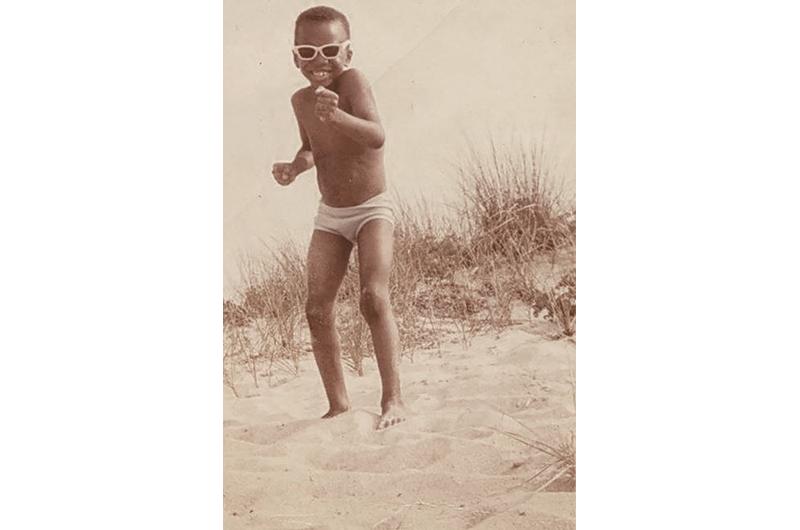

I first visited the Island as a child in the 1960s, staying in the cottage of my father’s late grandmother, Mattie Jones. She had bought the house in the Highlands section of Oak Bluffs in 1943 after seeing an ad in a Boston newspaper. Our story was just one of many in the long history of Black residents and visitors. By the time my great-grandmother settled in the Highlands, it was an established Black summer community: home to Shearer Cottage – the first guest house to welcome Black visitors on the Island – and many distinguished residents, including Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the writer Dorothy West, and Ralf Meshack Coleman, known as the dean of Boston’s Black theater.

As Dr. Phil Hart – former professor at the University of Massachusetts, former director of the Federation for Boston Community Schools, and longtime Vineyard vacationer – told me, “Black Americans found an accepting home in Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard over a century ago. They were able to buy homes and create a community defined by culture and social equality across the water from a more challenging social environment.”

Although the Vineyard did then, and continues today, to attract distinguished members of the Black community, not all early Black summer visitors to the Island were wealthy. Many were the families of late nineteenth-century laundresses and hairstylists, who accompanied their white Bostonian employers to the Island in the summer. Over time, some of these thrifty folks saved enough to purchase their employers’ guest cottages.

Those early summer residents invited their friends – chauffeurs, doormen, butlers – to stay with them. Blue-collar workers, merchant marines, schoolteachers, housewives, itinerant artists, and part-time actors mingled, their children and grandchildren becoming lifelong friends. As the community took hold, they were joined by doctors, lawyers, and other high achievers. In time, Black Bostonians, and to a lesser extent, New Yorkers, from all walks of life bought property in Oak Bluffs.

By the 1970s, when Boston made national headlines for violent attacks on Black students who participated in Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr.’s plan to force busing between predominantly white and Black areas of the city, Oak Bluffs was a well-established refuge. It was a place where I didn’t have to think about my complexion every day, and where my friends were far less likely to be judged by theirs.

In those days, people like me would come for the whole summer, staying with our grandmothers or mothers while some of our fathers stayed in the city during the week to work. (The Friday evening boat, which was typically filled with fathers arriving for the weekend, was known as the “Daddy Boat.”) With so much time on their hands, vacationers and neighbors got to know one another, and oftentimes became lifelong friends. It felt as if everyone in Oak Bluffs knew at least one member of every family. Small parties and cookouts hosted by Roxbury natives, such as my parents, were common. As were quiet evenings at home playing Sorry! or Scrabble. Unlike on the mainland, my parents never had to worry about my Island whereabouts from sunup to dark. My bike and the safety and quietness of the community afforded me freedom.

As I grew older, I spent much of my time at State Beach, house parties, small restaurants, or on the tennis and basketball courts at Niantic Park, the latter of which played an important role in the summer scene. Many of us, especially Baby Boomers, met both summer and local children, white and Black, through the summer basketball league in Oak Bluffs, which featured players of all genders ages seven through adulthood. I have friends who tell me they know 200 people from their years playing at Niantic Park in that league.

There wasn’t a go-go-go pace then, just long, leisurely summers from late June to Labor Day. But by the 1990s that began to change. As the number of nationally known Black vacationers increased – including Harvard Law professor Charles Ogletree, Harvard DuBois Institute founder and professor Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Clinton administration cabinet members and staff – organized conferences, panels, arts events, and book signings became commonplace.

Much to my mom’s chagrin, Oak Bluffs grew to be less of a place to relax, read at home, or entertain the company of longtime friends than to check the events calendar in the newspaper to ensure one wasn’t “missing anything.” Summers of forgetting what day and month it was gave way to marking one’s calendar for plays and author appearances. Of bringing dressier clothing to the cottage. Networking, hobnobbing, and marketing one’s services as a consultant, yoga instructor, or painter.

Films, such as The Inkwell (1994), and books, such as Dorothy West’s The Wedding (Anchor, 1995) and Lawrence Otis Graham’s Our Kind of People (Harper Perennial, 1999), furthered this perception, introducing a new generation of Black people to Martha’s Vineyard.

Some were drawn by the Island’s reputation for racial tolerance and safety; others by the opportunity to interact with their professional peers and to expose their children to that stratum of accomplished Black people. Still others came to check out the scenery: the Ocean Park bandstand, the rainbow-hued Camp Ground cottages, the Flying Horses, all of which have a long history of inclusivity. The Flying Horses, after all – the oldest continually operating carousel in the country – was a welcoming destination for Black visitors long before the Island’s reputation grew, back when jaws were a part of the face, not a blockbuster filmed on the Island.

Regardless of what drew them here, many felt the effects of the magic Race Machine once they arrived. As progressive as New York, D.C., and Boston are supposed to be today, I’ve heard Black Vineyard vacationers say summering here, in a place they’re not constantly focused on their complexion, adds “five years to my life.” I’ve witnessed Black people of all generations appear stress-free and relaxed in a manner I can’t really compare to anywhere else – perhaps it’s similar to the way Black expats have stated they felt living in Europe as jazz musicians, or Latin America as Negro League ballplayers.

The Vineyard isn’t a magical place free of racism. Slavery, though abolished relatively early, did exist here – as did, and perhaps does, housing discrimination. The Island bears many of the same scars and ills as the rest of the country. It has avoided the stigma associated with those scars, I believe, because of multigenerational Black vacation homeownership on this Island. Underneath the veneer of inclusion is the assumption that a Black stranger who is a Vineyard summer resident is a high achiever in business, education, or government.

Has the Island traded racism for classism? Perhaps – certainly to some extent. Dorothy West often stated, when interviewed about The Wedding, “Color is important, but class is more important.” Still, the lesson in all this for the rest of the U.S. is that if income and education levels were assumed equal between Blacks and others, ethnic stereotyping and profiling would be far less prevalent. If we could export the assumptions of Martha’s Vineyard elsewhere, Brown skin or African descent would not automatically signify poverty, inferior intellect, or criminality.

Of course, there is no way to “bottle” Martha’s Vineyard and force the mainland to drink it. Nor should we have to. That’s all the more reason I feel so unburdened once I disembark the ferry to the Island. I’m back inside the Race Machine. Others still notice I’m Black, but the sociocultural baggage that accompanies most of our U.S. experience since our transport on ships where we were enslaved is absent. The second I walk or drive or bicycle off the Steamship, onlookers think, “That guy is en route to his summer home.” Or, at the very least, a $600-$800 per night hotel, pricey dinners, and a week off from a professional occupation.

Whatever the positive stereotypes, I welcome them, given the alternative on too much of the mainland.

Bijan C. Bayne is a lifelong summer resident, author, screenwriter, and media consultant.

9 comments

9 comments

Comments (9)