In the shack on the Edgartown side of the Chappaquiddick ferry, Roy Hayes has posted a notice asking his captains and deckhands to suggest ways he might improve on the aging ferries he owns, the On Time II and III. (We’ll get to the myth-busting reason behind the name On Time in just a little while.) He plans to build two new boats, the first starting as early as this summer. The suggestions include recessing the vehicle tracks and engine covers so passengers don’t trip over them, installing engines that can readily use biodiesel, and angling the windows in the wheelhouses to prevent glare at night. One of the crew also suggests an all-expense-paid field trip to the San Juan Islands to “gather boat-building ideas.”

Which underscores what you might expect – it takes a sense of humor to run a ferry that sails just 527 feet each way and makes a trip every five minutes during the busiest hours of the summer. In the course of driving the ferry and taking tickets, a skipper and deckhand may travel over the same narrow and furiously tide-swept entranceway to the harbor seventy times or more during a regular six-hour stint. They run a pair of three-car ferries at right angles to recreational boat traffic that can be as heavy and heedless of others as anything you’ll behold on the Cross-Bronx Expressway. And they do it in a crisscrossing, back-and-forth ballet that might tempt a skipper and ticket taker, by the end of the day, to lapse into a kind of trance – but of course they never, ever can.

How deep a sense of humor? Peter Wells, a Chappaquiddicker who’s skippered the ferry since September 1974, remembers the days when he and another captain, Kenny Grant, would run the boats with the pilothouses as close to each other as possible. “You get this real feeling of speed,” he says. “We’d go by and slap hands and have water-balloon fights that you would not dare do now. I threw a water balloon at Kenny and it went right into a car. ‘Oh, you boys,’ the driver said.”

So a sense of humor, yes, but running the Chappy ferry seems to call on something else too, a borderless capacity to be amazed by the world above, ahead, and below – to notice the first time a bonito jumps in the harbor in summer, to remember the last time the ferry plowed her way through ice in winter. Skipper Robert Gilkes shows photographs of dawn moving through the seasons from north of Starbuck Neck in June to right between the gantries of the Chappy slip in December. Maddie LeCoq looks forward to a moon that will rise in a coppery total eclipse on a late-winter evening. Brad Fligor talks about how spring comes late to Edgartown, still later to Chappy, and latest of all to the narrows between them. It’ll be 60 degrees at noon on an early June day, he says, and “all of a sudden the sea breeze kicks in. You can see it coming up the harbor. And you just think, ‘Oh, it’s going to be 15 degrees colder in about twenty minutes.’ And sure enough, it comes right in, and you’ve got to put on another layer.”

But isn’t the job boring? People ask that all the time. Never, says Charlie Ross, who’s been skippering the ferry since 1985 and is now the senior full-time captain. “Every trip is different. Whether it’s the current or the weather or the people. A lot of people, they work in a store behind a counter all day,” he says, leaving that idea floating in the air as if it needs no elaboration. You get the impression that many captains on this short-haul run are in it for life, whether full-time or part-time. And even as castles begin to rise and sprawl on Chappy; even as the lines of cars and landscaping trucks have lengthened on the Edgartown side and the garbage and effluent trucks stack up coming back; even as the burden on the boats grows heavier and the wait to cross grows more unpredictable at either end, neither the skippers nor most anyone else who’s thought very much about the ferry can imagine how the service will ever change or move or expand in any meaningful way. We’ll get to the reasons behind that in just a little while too.

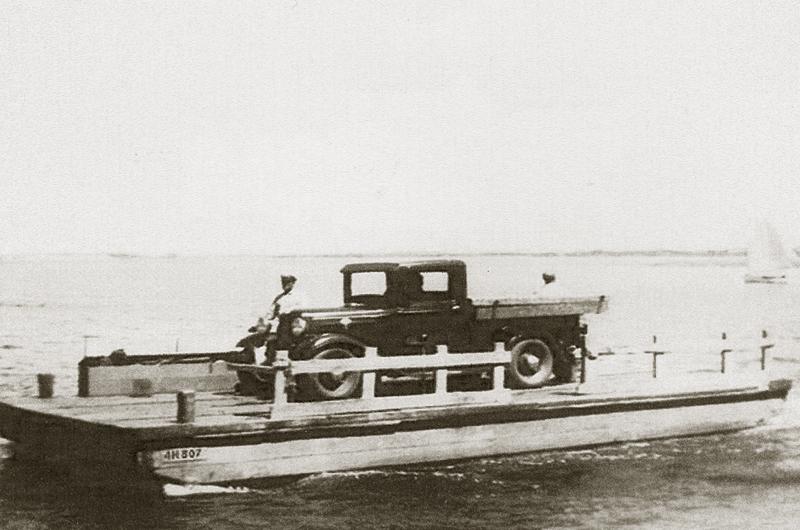

It’s fair to argue that the beginning of the end for rural Chappaquiddick came on July 17, 1912. On that clear and nearly windless Wednesday, a scow – possibly pulled by a nearly sightless but strong and well-practiced ferryman in a rowboat – carried the first automobile over to Chappy. It was rolled down a pair of wooden planks onto the beach at the Point and went “careering over hill and dale,” reported the Vineyard Gazette. The car belonged to Dr. Frank L. Marshall of Boston, a summer resident of Chappy, whose behavior at the wheel suggests he had no idea how portentous his little caper really was. “We are told the frequent honks as it proceeded to the Doctor’s place so aroused some of the staid inhabitants that Gov. Handy” – a Chappy figure who delivered goods by horse and wagon – “came to town to see what it was all about.”

We know that some sort of ferry was in service at least a hundred years before that first, fateful car bounced across the island. Dr. James Freeman, a founder of Unitarianism making a tour of the Vineyard, notes a ferry in an 1807 essay. But Chappy was rolling, grassy wilderness then, the few native Wampanoags long since edged off the loamiest hills so that the white settlers of the village could swim their cattle over to the 3,750-acre island and pasture them free-range in summer without fear of theft or predation. So little demand was there for a ferry that when Chappaquiddickers rose to ask for a licensed operation in March of 1885, the county commissioners decided that official sanction of such an ephemeral service was ridiculous and turned them down just eight weeks later.

But in November of that year, George Huxford, a Chappaquiddick boat-builder, began work on a skiff for the service. Charles B. Osborn, the son of a whaling master and himself an expert rigger, built a “stage” or pier just south of what is now North Wharf and Edgartown Marine and took charge of the new boat. Osborn had wanted to go a-whaling as his father had, but he would seldom, if ever, take a vessel farther from shore than the route between his ferry house and Chappaquiddick Point. For Charles Osborn had developed cataracts in both eyes when he was fourteen, and for the next thirty-five years, he would row back and forth to Chappy with his passengers, sometimes towing cattle that swam over to the summer pasturelands or pulling a raft laden with a Model T.

The fact that he was functionally blind seems to have troubled no one. The route was short and repetitive, and the years of his service were almost depressively quiet for Edgartown and the waters around it. The village had lost its whaling industry but not yet established itself as a summer resort. And Chappaquiddick was a Newfoundland-like frontier. “The most striking thing about those days was how little we had to go to town,” said the late William Pinney Sr., who first summered on the island in 1898 and whose story appears in a book of oral histories called Chappaquiddick, That Sometimes Separated But Never Equaled Island (Chappaquiddick Island Association, 1981). “Old Mr. Handy had a beautiful farm down near the dump back of Foster [Silva’s] and he came once a week from Edgartown with supplies. But most of the supplies we brought with us at the start of the summer. We had a barrel of flour and, of course, we had cooks and maids. I see no reason why people can’t still make bread. There is no reason to go to town every time you turn around.”

Frontier living delighted those early summer residents, but as the twentieth century rolled in, the conflicting sense of proximity and remoteness antagonized the twenty or so year-rounders who were trying to make a go of it on Chappy. In 1921, Osborn and his son Walstein (also practically blind, and “slow,” as they put it back then) yielded their skiff to James H. Yates, an affable oarsman who wore a vest, bow tie, and a blue yachting cap given to him by summer residents and inscribed Edgartown Ferryman 241 – the 241 apparently suggesting that he repay his benefactors by giving them two nickel rides for the price of one. But Chappy had lost its church and its school. The roads were still dirt tracks and sand. There was no electricity. And despite Dr. Marshall’s escapade with his car back in 1912, the ferry was still a rowboat.

So on January 25, 1925, the sixteen voting residents of the island asked the town to do a startling thing – build them a bridge.

It would be laid out at a narrow place down-harbor, landing just south of the entrance to Caleb’s Pond on the Chappy shore. It would be built of steel and cement in three spans, each 208 feet long and rising to 50 feet over the harbor. It would cost $100,000 to construct, $200 a year to maintain, and last 400 years. The investment would be entirely paid for by an instantaneous, exponential rise in the value of land on Chappaquiddick and the property taxes that this increase would generate. Would not a car ferry be simpler, the petitioners asked rhetorically in a petition to the town. Such a service would require at least two men “who will not become intoxicated or sick, and will attend, without failure, to their duties – there may be many such men,” wrote the islanders, but paying for them and the rest of the operation would “charge close to $10,000 a year.”

At town meeting that February, the vote to indefinitely postpone the whole question passed, 99 to 58.

Fine, said the islanders: We want out. In 1926, fifteen of the sixteen voters began filing paperwork to secede from Edgartown and establish a Town of Chappaquiddick Inc. “If it wasn’t for the $100,000 yearly shellfish catch, the grounds of which are mostly in Chappaquiddick waters,” said Benjamin G. Collins of the main village at a town meeting on the subject, “I would say, ‘Go and God bless you.’” A committee of state legislators came down from Boston to inspect what they recognized to be a unique situation – “an island dependency cut off from its parent town.” Jimmy Yates rowed the committee over to the island. Representative Josiah Babcock of Milton stepped over the side of the skiff onto what he thought was Chappaquiddick Point. But it was foggy, and he found himself standing in water up to his waist. The legislators returned to Beacon Hill and invited the Chappaquiddickers to rescind their petition. This they did – in return for an inferred county promise of a licensed ferry service they could live with, and perhaps even thrive on.

Sometime in the first week of April 1935 – the precise date is lost to us – a low-slung, bargelike craft, thirty feet long with a sharply cutaway bow and stern, was lifted from Chappaquiddick Point by a steam-powered lighter and set down gently on the water at the entrance to the harbor. A few weeks later, as Anthony Bettencourt got ready to fire up her rebuilt Chrysler Ace ninety-horse gasoline engine for the first time, Dr. William Andrews, a Chappy summer resident standing on the Point, offered a morale-boosting $20 bet that the new craft, which Tony had spent a frigid winter building, would never work. “Doc,” said Tony, “I wouldn’t dare to bet. I don’t know if it will work or not myself. This is sort of a little invention of my own.” Tony pressed the starter and put the engine in gear. “Oh, boy!” he remembered years later. “I sailed around the harbor with everybody tooting their horns. I had a horn on her and tooted it too.”

“Tony Midge” Bettencourt – the nickname came from his height – really had invented something brand new: a barge that did not require a tug, but drove itself. So unimaginable was this self-propelled, car-carrying little slab that Tony Midge had to make a special trip to the Custom House in Boston with a picture of the ferry in operation to prove that it actually worked. It took the commonwealth a year to create the category of “motor scow” to register her. Joseph Chase Allen, waterfront correspondent for the Gazette, suggested that the ferry be called the City of Chappaquiddick, a sly nod to the would-be secessionists of 1926. The name stuck.

On Chappy and in many parts of Edgartown, Tony Midge – he was born December 31, 1899, on the island of Graciosa in the Azores, moved to the Vineyard when he was two, and died in 1970, thirty-five years to the month after the maiden voyage of his extraordinary, self-driving little scow – is remembered in almost saintly terms (even though his time as owner would end in conflict). “I never got to meet him,” says his daughter-in-law Nancy Bettencourt, who with her husband Skip lives on Chappy. “But I think he just loved people. The stories that we hear from people are all about the interaction and the social part of it.” There were only five families on the island in the 1930s, but Tony Midge would keep track of the Chappy summer kids who’d crossed over to town during the day and failed to come home at night. “He would go down at midnight and pick up the kids from the yacht club. They’d all tell stories about that, how he’d watch for them and take care of them. ‘C’mon, children. Come aboard, children,’ he would say. He called everybody children.”

The service remained essentially a ferry to wilderness, but in the late 1930s there came a trifecta of dis-asters that might have made everyone wonder, in retrospect, whether a bridge was such a bad idea. In the Hurricane of 1938, the City of Chappaquiddick was deliberately sunk in its slip to save it from the onrushing wreckage of boats and piers and buildings (it was raised and returned to service a few days later). On an August night in 1939, an auxiliary passenger ferry caught fire as it crossed to Chappy, forcing everybody on board to jump into the channel. But the most symphonic calamity occurred at 7:25 on the evening of July 23, 1937. In those days it was still quiet enough for seaplanes to land inside Edgartown harbor – even on the Friday of the yacht club regatta.

The plane, piloted by a man named Alfred R. Leckshied, who had held his license since 1918 and logged more than seven thousand hours in the air, touched down just inside the lighthouse. Moving at a good clip as Leckshied fought the current and a crosswind, the plane bore down on Memorial Wharf, where the City of Chappaquiddick was pulling out of a slip built for it by the county. Foster B. Silva, nephew of Tony Midge and skipper of the ferry that day, saw the plane trying to turn away. “It was an awful sight to see that propeller grinding toward us,” he said. A wing clipped a laundry truck on the ferry, tipping it over onto a railing and sweeping a passenger, Charles Johnson, into the water with “serious injuries,” according to the Gazette account. The skipper of the ferry, the driver of the van, and another passenger jumped as the plane struck. They swam to shore near the slip.

The plane pitched forward and floated, tail up, against a Coast Guard vessel tied to the wharf. Two civilians and a boatswain’s mate leaped from the pier and pulled the pilot and three passengers through a submerged window. Another passenger, James T. Baldwin, seated behind the pilot, could not undo his seat belt. Finally freeing himself, Baldwin “worked his way up into the tail of the plane where there was an air pocket,” said the Gazette. “He gave considerable help to Mrs. [Johnfritz] Achelis, pushing her ahead of him into the tail, and telling her there was no danger as long as she kept her head in the air.” A Coast Guardsman and a civilian had dropped down onto the tail and hacked away at the fuselage with an axe and a knife. They pulled Baldwin and Mrs. Achelis out through the hole.

The grandeur of this catastrophe overshadowed a symbolic point overlooked at the time but worth noting seventy Julys later: A laundry truck was heading to Chappaquiddick that day. In two years, a single, self-propelled, car-carrying, thirty-foot raft had swept away the whole sense of independence you had to have if you wanted to live on Chappaquiddick for any length of time. Folks who used a laundry service had no need to store flour by the barrel or have their cooks bake bread if it could be delivered. And Chappaquiddickers of all types could now go to town – every time they turned around – by car as easily as on foot. The wicked, suburbanizing promise of Dr. Marshall’s 1912 automotive stunt was now entirely fulfilled.

Except Chappaquiddickers couldn’t really go to town every time they turned around. Not quite. Not yet.

In the middle of February 1948, the county commissioners, who in those days licensed the ferryman and set the rates (duties performed by the Edgartown selectmen today), met with townspeople to consider Tony Bettencourt’s request that fares be raised from a round-trip rate of 12 cents to 20 cents per passenger and $1 to $1.50 per car (equivalent to $1.70 and $12.80 today, as compared to the current round-trip prices of $3 and $10). Year-round Chappy residents groused that rates that high would make dinner in town or a night at the theater impossible. Several complained of the service they were now getting from Bettencourt.

In the winter, one woman pointed out, the ferry stops running from noon to three while the ferryman “goes on a shopping tour or is gunning, eating, or feeding his livestock.” Nighttime service, she added, depended “on his whims and temperament.” Bettencourt felt that everything he had done to revolutionize the ferry and link Chappy to town was now being taken for granted. At the meeting, he was heard to murmur an uncharacteristic threat: “You know now what kind of service you’ll get.” The rate increase was turned down. A report criticized everything from the shelters at the slips to the condition of the City of Chappaquiddick itself. On June 30, 1948, Tony Bettencourt resigned,

effective four weeks later.

“I think he provided a good service for a lot of years,” says his son Skip. “And then I think he got tired. Running people back and forth – it wasn’t a regular schedule; they would call him. Then the town politics came into it. I’m sure it changed his whole attitude and made things even tougher. He just wanted out.”

When the county commissioners asked him whether he would lease or sell his ferry to a newly licensed operator, Bettencourt had a surprising answer: Nope. Effective August 2, he was going to use the City of Chappaquiddick to go scalloping, repair piers, and take charter parties to picnic on remote Chappy beaches. Foster B. Silva, his nephew, was chosen to take over the service on July 16. He had sixteen days to find a replacement ferry. But there was no self-propelled scow anything like the City of Chappaquiddick on the whole of the eastern seaboard. What to do?

It became the waterfront equivalent of a barn-raising. Captain Samuel B. Norton, a renowned Edgartown sailor, builder, and house mover, took charge of the whole project. Assisting him was Manuel Swartz Roberts, a famous boat builder who worked out of what is now the Old Sculpin Gallery. The craftsmen set up shop outdoors by Memorial Wharf, and the race was on. “There will be eleven days from the time the lumber arrives [to] the commissioning of the finished craft, and this means putting a lot of old time Vineyard resourcefulness to work,” Captain Norton told the Gazette. “There won’t be eight hour days.”

His son Floyd, who was nineteen that summer and helped to build the scow, recalls Edgartonians flocking around every day to watch the new ferry take shape upside down in the parking lot. They brought coffee and food to the shipwrights and cheered them on. “People were excited to see all the activity, and they wanted to be part of it, I guess,” says Floyd, who would serve as a captain of the ferry later in life. “And they would help. They’d come and they’d saw the planks and they’d carry them over. Even people that weren’t part of the building crew.”

Because the lumber had arrived a few hours late the first day, the boat builders missed the morning tide on August 2 and were forced to launch the boxy new ferry that evening. Tony Bettencourt agreed to keep the City of Chappaquiddick in service the extra day so the new boat could begin her service with the morning light. And her name? Take note, tour-bus drivers and arrivistes: It’s emphatically not because she has no schedule, but because she made that very tight launching deadline of Sunday, August 2, 1948, that the new boat – and both of her successors – have been called On Time.

In the early morning hours of Saturday, July 19, 1969, Jared N. Grant, who’d bought the ferry in 1966, was sitting on the porch of the ferry house on the Edgartown side after skippering the On Time to 12:00 a.m. “I sat down on the dock until after two o’clock splicing ropes, because you closed at midnight,” he says. But that night “it was so hot, and I was so wound up. When you worked the night shift, I never could go home and just go to sleep.” Around six o’clock the previous evening, one of his captains, the late Dick Hewitt, had pointed out Senator Edward M. Kennedy in a group of men who were headed over to the island on foot. In the darkness of the porch eight hours later, Jerry Grant felt his nerves begin to settle down. When he rose to go home, everything was quiet on the Edgartown side, the Chappy side, and the water in between.

It would never be quite that way again.

The accident at the Dike Bridge – wags sometimes call it the most consequential car accident in world history – made Chappaquiddick a byword in the political lexicon. And it upended the private little ferry service forever. The business had passed from Foster B. Silva to a former harbor master named George T. Silva at the end of 1953 and thence to Laurence A. Mercier, who purchased it in 1962 at the age of twenty-one, the youngest owner on record. Jerry Grant, himself only twenty-nine that summer of 1969, found himself serving as the only gatekeeper to a horde of newsmen and oglers from all around the planet.

“I just remember we went absolutely bonkers,” says Jerry. “About three days after the Kennedy thing, something happened to the On Time. I’ve forgotten what; something broke down on it.” George T. Silva had bought the old City of Chappaquiddick to use as a spare ferry, and now it was Jerry’s resilient but rickety backup boat. “And I remember one night, something went wrong on the City of Chappaquiddick. We had them both down. And we figured we could do the City of Chappaquiddick quicker than the On Time. John Ahlbum and I” – Ahlbum owned the Depot Corner Service Station in town – “we went down there, we worked until three in the morning on the engine on that one. So we’d have it for the next day.” What saved Chappy from being entirely overrun that summer was that, despite the pleading of the public and the offers of payola from the press, Jerry refused to run his ferry a minute longer than regular hours. “If I wasn’t going to do it for the residents, I wasn’t going to do it for them. I didn’t even start it. We had hours and that’s what we’re going to run,” he says.

That summer Jerry Grant was building a new ferry in his backyard on the road to Katama. The On Time II measured fifty-two feet, could carry three cars rather than two (as the original did) and unlike its predecessors, had propellers at either end so that it did not have to back out of its slip, turn around, and unload cars by backing them off the boat. But even these efficiencies were not enough to carry the throngs who now wanted to see the bridge, loll on the golden ribbon of East Beach, or cast into the bluefish-laden rips that strung seaward from the elbow of Wasque Point. In 1975, he built the On Time III, sixty-two feet long, selling the original On Time to Edgartown Marine to serve as a stationary barge supplying fresh water to yachtsmen. And still, at the height of the high season, the two double-enders could not always get everyone where they wanted to go when they wanted to get there.

In early August 1985, Chief George Searle of the Edgartown police reported to the selectmen that he and a patrolman were struggling to manage a line of cars that stretched from the ferry slip up the length of Daggett Street to North Water, and then along Simpson’s Lane halfway back to North Summer. “It’s been like this every day for three weeks,” Chief Searle said. “We’re having to use two men for this problem. It’s terrible, a waste.”

The lines would keep growing after that, sometimes reaching Pease’s Point Way in Edgartown and three-tenths of a mile back to the beach club on Chappy. Residents of the island learned that it was no longer possible to go to Edgartown every time they turned around. If they wanted to run errands in a car, some afternoons they couldn’t go at all.

Despite the fact that Chappy is thought of as an island, most of the time it isn’t – a barrier beach links it to Katama and protects down-harbor from the Atlantic. But no longer. This past April, the wind and tides of a great three-day northeaster busted through South Beach, severing Chappy from the Vineyard for the first time since the winter of 1976. Traffic to and from the newly re-separated island, which for the last three years has held steady in July and August at about 80,000 passengers and 32,000 cars round-trip per month, looked like it might increase markedly this summer as fishermen and beachgoers in four-wheel-drive vehicles added themselves to the queue on either side. For the first time in a generation, and for as long as nature keeps the cut open, the ferry is now the only way anyone without a boat can reach Chappaquiddick.

Which leads to a question asked fitfully over the years as the lines lengthen each spring and shorten in late fall: What is to be done to accommodate all this traffic? At press time, the town was considering purchasing lots at North Water Street and Simpson’s Lane to help move traffic off of Simpson’s Lane. But the consensus among those who work on the boats, and many others who have considered the whole problem:

Nothing big.

With Debbie Grant, his wife at the time, Roy Hayes – a native of the Bronx who worked in classic car–restoration shops, ran a set-building plant for the Broadway impresario David Merrick, worked above the Philippine Trench on a research vessel, and built furniture and houses before moving to the Island in June 1969 – bought the ferry from Jerry Grant in January 1988. (Debbie is Jerry’s daughter and the first woman ever licensed to skipper the ferry.) When Roy and Debbie divorced in 1997, Roy took sole ownership. He’s about to turn sixty-two and expects to sell the ferry in the next four to six years. Before he does, he wants to build two boats to replace the ferries he has now.

He plans to duplicate the On Time III in almost every respect: no more capacity for people, cars, or trucks.

“There’s a lot of discussion,” says Roy of the folks he serves on Chappy, “and it’s from new people. They want two six-car boats because they want to move the cars faster. And I’ve always said, ‘Well, wait a minute. If you move all the cars faster, all you’re going to do is make Chappaquiddick more attractive. We’re already worried about how many houses are going to be built over there. If people can get in line and zip over there, you’re just going to fill that ferry line right back up again with more people trying to go to the beach on Chappaquiddick.’”

Well, what about moving it someplace down-harbor during the high season, away from traffic ashore and afloat – a suggestion discussed from time to time? No, argues Roy: Downtown would lose the revenue the ferry traffic brings. You’d have to build more or bigger boats to compensate for the greater distance. Neighbors living in waterfront homes worth tens of millions of dollars would fight to the death to keep from having the ferry move next door.

Charlie Ross, the senior captain, just smiles at the whole idea: “Neither you or I would live long enough to see all the permits go in,” he says. “I just can’t see a lot of changes.”

So the ferry service that the county licensed as a private service between downtown Edgartown and Chappaquiddick Point so long ago is the ferry service we’ll almost certainly have until the waters rise and the dry land turns to shoal water. Roger Becker, a builder who moved to Chappy in 1985 and lives off a dirt road with his wife Claire Thacher, agrees that with respect to the Chappy ferry, what has always been will always be. He mulls over the implications for those who have chosen to live what some might still call the frontier life:

“You would think that having lived here steadily for twenty years and more that we’d have it all settled in our minds. But we still say, ‘Jeez, wouldn’t it be nice to live over in Katama, and we could just drive to the hockey game or anywhere we wanted and then drive home without waiting in the ferry line.’ On the other hand, you can walk down the road a mile before a car will pass you. Knowing the neighbors. Having this island in common. I think this question is alive for a lot of people over here,” he says.

It’s just like the Vineyard as a whole: If Chappy residents didn’t find themselves thinking about ferries, bottlenecks, and lines, everyone else would want to live there too. “It would be Katama,” Roger agrees. “Lovely, but in a different way.”

How Hard Can it Be to Drive the Chappy Ferry?

I actually got kind of good at it. A dozen times this winter, skippers Brad Fligor and Maddie LeCoq let me drive the Chappy ferry. The rules were obvious: No other passengers on board, no cars, no boat traffic coming either way. They gave me a few pointers: Figure out which way the tide is running and steer a parabolic course against it. Give ’er gas all the way into the slip – with the On Time III (or the Three, as the captains call it), if you coast, you lose steering. You don’t want to lose steering.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)