Wind is a persistent natural phenomenon on the Vineyard, seemingly ever-present and strong enough to attract the nation’s most powerful offshore wind farm, sixty-two soaring towers with blades longer than the wingspan of the largest airliner, soon to rise out of the sea fifteen miles south of the Island. The breezes diminish not a smidge after they sweep onshore. It’s enough to make you wish you could find shelter in a bunker. Even better, a bunker with a dry sauna, a shower, and generous teak lounge chairs in which to recline in a plush cotton robe and gaze at the sky.

The space doesn’t need to be big; actually, small would be more like it: a cozy place where you feel embraced and the wind can’t get past the velvet rope.

“It’s, like, the size of a Volkswagen bus,” said Michael Van Valkenburgh, who designed and led construction of this rarefied hideout. “And I decided to put thirty or forty thousand tons of rocks in there and a few trees.”

The comment is classic Van Valkenburgh, founder and creative lead of Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), which has offices in Brooklyn, Denver, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. MVVA is renowned for its large parks –notably Brooklyn Bridge Park (eighty-five acres spanning 1.3 miles of East River waterfront and New York Harbor), which won the 2021 Rosa Barba International Landscape Prize; Rotterdam’s upcoming fifty-four-acre Rijnhavenpark; and the CityArchRiver Project, which overhauled Gateway Arch National Park to (among other things) greatly enhance the connection between downtown St. Louis and the ninety-one-acre site of Eero Saarinen’s iconic Gateway Arch.

As to why the quote is “classic Van Valkenburgh,” it’s a funny humblebrag about a playfully perverse little garden.

Just 350 square feet, the Sauna Garden stands – or rather, sits – as his smallest design. It is perverse to pile huge boulders into a tiny subterranean vault. It is funny to cite a Volkswagen bus as the metaphor for the garden’s dimensions. And it is a humblebrag because after forty years of creating works of often astounding beauty and technical achievement, Van Valkenburgh has gained ample self-awareness and -assuredness to dispense with modesty. If he were modest, it would be falsely so, because the landscape architect whose stature is routinely compared to that of Frederick Law Olmsted – and who is the Charles Eliot professor in practice of landscape architecture, emeritus, at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design – cannot be a paragon of his profession and genuinely self-effacing at once.

This is not to suggest that Van Valkenburgh, who is a seasonal resident of Chilmark and has designed projects on the Island since 1984, is a braggart. On the contrary, he refuses to be cornered into lengthy conversations about his work. Those who know him well will tell you that instead of blabbing about his great parks he’s more apt to speak glowingly about his family, especially his grandchildren, and to discuss his favorite avocations: cooking, baking, and painting. (He also loves to go on about the beauty and unique attributes of trees.) And when he does talk about his professional creations, he is quick to credit his collaborators – artists, architects, engineers, and other landscape architects – and to deflect the notion of sole authorship, also doling out praise for his partners and associates at MVVA.

It’s both fascinating and quirky that someone capable of envisioning and realizing massive public green spaces would dabble in a sliver of a place like the Sauna Garden. On the other hand, it is unsurprising for two primary reasons:

One, Van Valkenburgh takes pride in his small works, including Teardrop Park, which covers just 1.8 acres on Manhattan’s Lower West Side, and the Monk’s Garden at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, a 7,500-square-foot maze of curvilinear brick paths lined by dense, highly textured planting. Van Valkenburgh likes to say that Monk’s Garden is a place to “get lost.” It is a refuge that invites wandering, introspection, and a sense of inner calmness. It is also an antidote to the museum’s wildly diverse art collection and chockablock presentation. The museum takes your breath away. Monk’s Garden allows you to breathe. It is the epitome of shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, the Japanese practice of spending time in nature to promote emotional well-being. The Sauna Garden takes this to the next level, not only because it is tiny but also because it combines shinrin-yoku with actual bathing, in the heat of the sauna as well as in the shower of water spilling out of the fieldstone wall.

And two, the project came about because of a long-standing relationship, something in which Van Valkenburgh places a lot of stock. He had worked on other parts of the client’s site; the idea to build this garden came years later, after the sauna and adjacent pool complex were complete. “This is a rather extensive residential project,” he said. “We were not asked to work on it until the whole thing was pretty far along.”

When the client sensed that the timing was right, Van Valkenburgh got the call to start working. “She’s intuitive about who she trusts,” he said. “Making a garden for somebody, you have a kind of connection and there’s a trust there. I can’t remember her exact words, but essentially, she said, ‘I know you’ll make something beautiful. Can you come up with a plan?’”

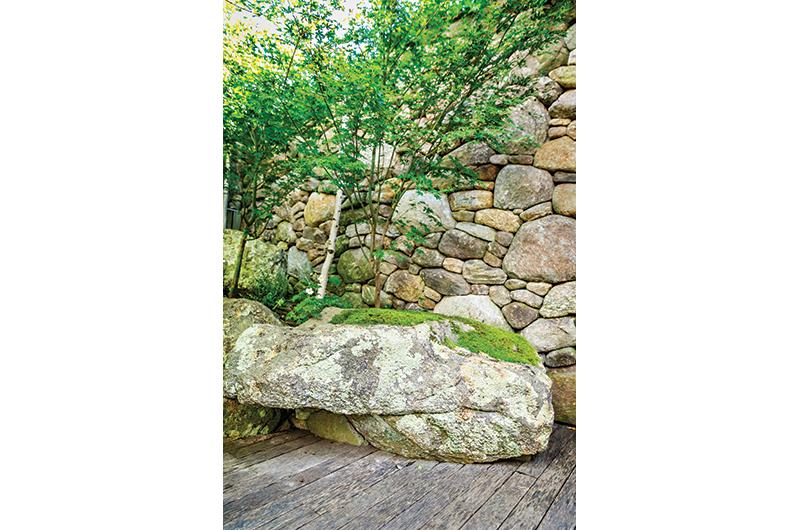

As with every project that Van Valkenburgh takes on, the Sauna Garden presented existing conditions, namely, the sauna, a sunken rectangular space, a stone wall, and a staircase beside that wall providing access from ground level.

“The site is in a flat part of the Island quite near the water, and it’s exceptionally windy,” he said. “It’s a very important thing in extremely windy sites to recognize microclimates. This is a place that’s wind protected. You wouldn’t normally think of trees and boulders, or mosses and ground covers, but they are all in the space. It’s an abrupt shift from the environment above ground. That’s just something I’m really into, abrupt shifts.”

While the garden’s atmospheric change may be abrupt, it’s not jarring. That was part of his intent.

“You go down these stairs and it’s like a whole other thing,” Van Valkenburgh said. “Taking off your clothes, going into an interior space that’s very hot and moist – it’s part of what’s magical about going to a sauna or bath. You escape the elements and become attuned to your feelings and senses. Being alive is all about that, isn’t it?”

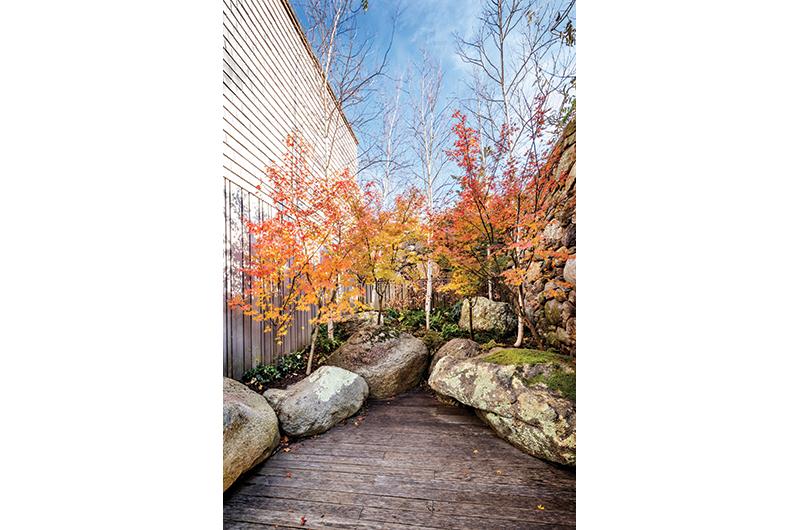

As a landscape design, the Sauna Garden bears a few of Van Valkenburgh’s hallmarks. Importantly, it feels at once natural and artificial. The artifice smacks you in the face. Without human intervention, there is simply no way that a perfectly rectangular subterranean garden with a deposit of glacial boulders, Technicolor dwarf Japanese maples, wispy birch trees, ground cover including rock-cap ferns, and three types of mosses could come into being. At the same time, the composition of the garden’s elements feels like something you might stumble upon during a hike in a lush forest. The vertical staging of ground-cover plants, the understory of Japanese maples, and the canopy of birches is distinctly naturalistic, mirroring a woodland habitat.

This idea, which Van Valkenburgh sometimes calls “constructed nature,” is contradictory on its face. If his gardens weren’t so inviting, invigorating, beguiling, lovely to look at, and untethered from convention, they would generate dissonance. Therefore his work, in general, and creations like the Sauna Garden, in particular, is sort of perverse, not at all in a creepy or suggestive way, but rather because they possess a harmless kind of impossibility.

Consider this: a ruin is not built but rather occurs naturally as a building or buildings decay over time, often overtaken by vegetation. But at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Van Valkenburgh designed what is sometimes referred to as the ruin garden (proper name: Elizabeth Scholtz Woodland Garden). It consists of a single-story concrete shell that fits the footprint of a Brooklyn brownstone and has rectangular voids in the walls, suggesting doors and window frames. Out of a bushy layer of ground cover grow vines such as Virginia Creeper, clinging to the concrete’s brutalist surface. Trees sprout up into the open “roof,” which is sheltered by a towering canopy of decades-old oak limbs. Through the glassless “windows” one sees more vegetation in the foreground, middle distance, and background. It’s clear that time and the elements did not produce this carefully staged landscape, and yet it feels eerily natural.

More evidence of Van Valkenburgh’s hand in the Sauna Garden can be seen in its seasonal changeability and scale. “There is a thing going on in that garden that I really like, which is a double order of canopy,” Van Valkenburgh said, referring to the dwarf Japanese maples, which are no more than six feet tall, and the gray birch trees, whose upper branches pierce the plane at ground level. “One layer stands up tall and is subject to the wind, and another layer is tucked in [below].” Gradual seasonal changes present themselves, in part, because the birches drop their leaves first and then the maples follow suit. In the spring, the maple leaves are bright green, but in time they put on a colorful show. One specimen, the Murasaki kiyohime maple, begins the growing season with lime-green foliage, which in summer becomes dark green with purplish-red borders. In the fall the leaves take on a golden hue tinged with orange and red.

It’s safe to say that nothing like the Sauna Garden exists elsewhere. Its reason for being and the person who dreamed it up are unique to the Vineyard. It’s even more likely that few people will lay eyes upon this hidden gem. And yet it’s one more example of the man who is known best for big statement parks throughout the world leaving his unique mark on the Vineyard.

As Van Valkenburgh said: “It’s a little bit of the Island moved to somewhere it’s not really supposed to be, but with a wink and a smile.”