If your idea of what it means to be an artist on Martha’s Vineyard is a rose-colored-glasses vision of an easygoing life, being inspired by nature, and the time to make art, then you haven’t met Terry Crimmen.

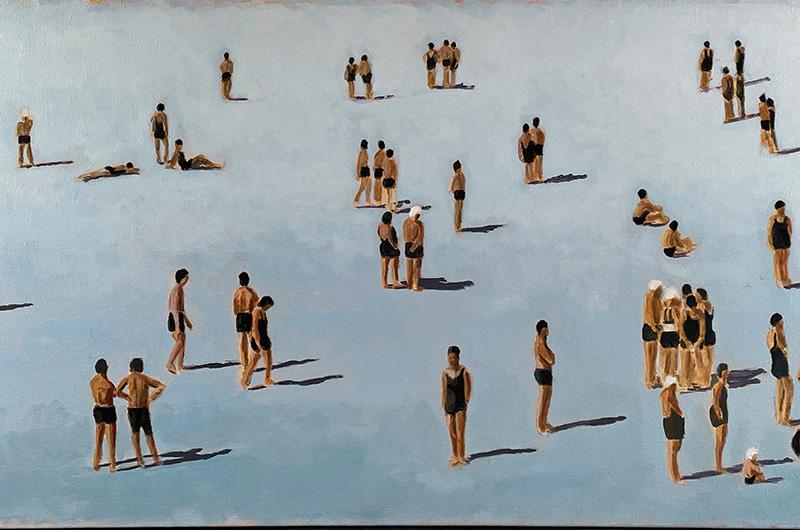

The painter – known for his large, light-inflected, shadow-filled still lifes of life vests, postage stamps, street signs, and sepia-tinted beach scenes based on vintage photographs – begins his day at 4:30 a.m. to get in a few hours of painting before a full day of work as a caretaker. He doesn’t relax at home in the evening: he’s back in his studio until 11 p.m.

As Fourth of July weekend 2021 approached, Crimmen’s artistic and professional lives were at full tilt. On a hot Thursday morning, he was preparing for the 3 p.m. arrival of a homeowner and had just finished moving an inflatable trampoline to a mooring at one of the five houses that he oversees.

Equally pressing, if not more, was the deadline to complete paintings for his annual exhibit at the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury. Crimmen was fast approaching the day on which he would take his new work to Chris Morse, who owns the gallery and represents Crimmen, to select which fourteen paintings would be featured in the exhibit. And he was behind on some commissions.

But the West Tisbury resident was not complaining. Crimmen feels fortunate to live, work, and be painting on an Island that instantly felt like home when he arrived here in October 1994. “You know how everybody complains about the inconvenience? You’ve got to wait two weeks for an air conditioner repair? I love that,” he said with a laugh. “Fine, whatever. You put up with it. It’s the cost of living here.”

Crimmen, born in Buffalo, New York, was raised in two opposing climates: Canada and Florida. His family moved to a cottage in Thunder Bay, Ontario, on Lake Superior – large enough to house his parents and their twelve children – when he was four years old. By the time Crimmen’s father sent him to finish high school in Winter Park, Florida, he had to take American history four times: the history that the artist was familiar with was Canadian.

Crimmen remained in Florida until he was twenty-nine, living in Fort Lauderdale and working for a company that created large-scale visual displays for department stores such as Macy’s. He also tended bar at a high-end venue and made more money in one night than in a whole week at his “day job.” The bartending experience came in handy when the visual display company went under after an employee committed bank fraud.

Throughout these times, Crimmen drew. “I drew all the time, for as long as I can remember. I had people around who encouraged me. My dad owned a bunch of businesses, including five nightclubs, and he drew all of his own logos freehand.” One of his brothers and a sister also painted. And like many artists, he was imprinted early by a teacher’s encouragement. For Crimmen, it was Mr. Dickerson, his first-grade art teacher. “Think of the most eccentric, crazy artist you can ever imagine. That was him….He winked, gave me a thumbs up, and said, ‘Good job.’”

At age four, he made his first visit to Buffalo’s legendary Albright-Knox Museum. Any time that his family returned to Buffalo from Canada, he visited the museum. He feels that he grew up wandering its galleries, amazed by the scale of the works there. He dreamed of one day creating something like them. Although he no longer lives near the museum, his loyalty is such that he remains an Albright-Knox member.

Crimmen’s artistry, combined with a practical experience in industrial display, parlayed into a busy life working as a decorative painter once he moved to the Vineyard. He worked for a company of twenty-five to thirty employees that handled everything from exterior house painting to interior finishes, and decorative painting to furniture repair.

He was successful at it because he knew colors and understood color mixing. To achieve a faux mahogany finish, he’d first paint the wood bright pink, then go over it with purple, followed by crimson to bring out the mahogany. “You have to understand about the color underneath and where you start from,” Crimmen explained. “Otherwise, the finish would come out just flat black.”

Painting in layers is what you’ll see in any of Crimmen’s works that hang on the walls of the Granary Gallery now – as well as what he has shown at Seaworthy Gallery and The Workshop, both in Vineyard Haven. From the bright primary reds and blues of his series depicting buoys floating in water to the more delicate, almost ghost-like figures walking beach shores in a series he created with vintage photographs as a visual cue, he layers his paint to emphasize light, create shadow, and foreground the objects he wants the viewer to focus on.

The results are sometimes reminiscent of Jasper Johns or David Hockney, two painters whom he admires. Critics, gallerists, and buyers also have likened his work to Edward Hopper. Yet the works don’t fall solidly into any categories that are used to label an artist’s work. “Terry is an original. I don’t know that there’s an ‘ism’ for him; his work doesn’t fit into a box,” Granary Gallery owner Morse enthused. “There is variety in

what he’s creating; he’s using so many different styles and voices. He’s trying everything. It’s great.”

Crimmen began making paintings approximately ten years ago on a lark. “My sister and I walked into a gallery in downtown Edgartown. She said, ‘I want that painting.’ It cost $4,000. I said, ‘I’ll make you one at home.’ Someone had bought me a set of paints a year or two before that, so I went into the basement and painted it for her. It was a landscape. She still has it on her mantel at her house.” Shortly after, Crimmen “tagged along” when his longtime partner Tara Kenny took a three-day seminar with Bob Murphy at Cape Cod Art. He was having fun, painting just for his own joy.

“When people ask, ‘How do you start painting?’ I say, ‘Just Google it,’” Crimmen advised. “One of the places I looked up said you have to make 100 paintings before you’re a painter. By the time you get to 100, you should know how to paint. So, I knocked out 100 paintings in the basement. They were rip-offs of every artist on this Island!”

Many of those artists are now his friends and the people he counts on for critique, support, and the occasional art supply. Crimmen and Kenny commit to attending all of the Island’s gallery shows each summer. That’s a full-time job in and of itself.

His generosity of spirit toward other artists is noted by those around him. “Terry has genuine appreciation of those he is working in concert with,” Morse said. “He doesn’t have an air of competitiveness; he cares about other artists and their growth as well as his own ability to learn and grow.” That camaraderie was manifested when Morse grouped Crimmen with his friends and fellow painters Kenneth Vincent and Dan VanLandingham, who are known for their landscapes, for the 2021 Granary exhibit. Leading up to it, Crimmen playfully joked that he felt pressure to include seascapes in his portion of the show.

Crimmen met and bought a painting from VanLandingham when the latter was eighteen; in 2013, the two would go on, with Kenny and Lauren Coggins-Tuttle, to open The Workshop on Beach Road in Vineyard Haven. Crimmen remembers his days at The Workshop as a mostly happy time. He had his own studio space there; he enjoyed giving people a chance to show their work; and Simone DeSorcy was a great landlady. Gina Stanley – owner of the ArtCliff Diner across the street – supported many of the artists who worked and showed there, buying works shown and created at The Workshop.

But after four years, Crimmen decided to give up his role there. “Sitting in a gallery is the worst thing in the world,” he said with a smile. “It should be put on the CIA’s list of tortures.” An eleven-and-a-half-by-twenty-four-foot bike shed in his backyard was repurposed to become his painting studio – but the size of the shed meant finding a different scale for his work compared to the space at The Workshop.

He also faced the challenge of finding Island representation and knew well how hard it was for Island artists to find places to show and sell work. This was when Crimmen set his sights on being represented by Morse at the Granary. “At the time, he was painting objects like propellers,” Morse remembered. “I thought the way he was composing them was really effective. He would give a little dignity to something that was maybe being discarded elsewhere.” After a month of persuasion, Morse agreed to take ten paintings to show and sell. Crimmen has been represented by the Granary ever since.

Morse and a bevy of clients who buy his work on Instagram keep Crimmen busy. Each year, he chooses a theme to depict and doesn’t paint the theme again once he has completed a series of paintings on it.

There’s an exception to that rule: life jackets have proved extremely popular. Crimmen is still busy filling orders for them beyond the fourteen commissioned paintings he has already completed this year. He recently set a new challenge for himself with the series: painting them in the style of other artists he admires. Recent additions include life jackets reminiscent of works by Jasper Johns and Damien Hirst. “I still paint for fun. But now I’m making paintings to sell them.”

He chose the working waterfront as his 2021 theme. But he didn’t paint the “pretty” Edgartown Harbor, with its sailboats and flags. Instead, Crimmen focused on the industrial waterfront in Vineyard Haven.

“It never got the attention that it needed,” Crimmen explained. “This year is about honoring the people who actually live here. When we were at The Workshop, our gallery was right there, so I’ve been thinking about this for about six or seven years. I’ve done some paintings of the Martha’s Vineyard Shipyard and of the DeSorcy and Gannon and Benjamin buildings. I have a video standing there the day before Memorial Day [in 2021] and the day after. The difference in the harbor is so funny; what a difference a day makes.” Morse praised these new works for the “grit and grime,” noting that Crimmen didn’t “sterilize” the look on canvas. It proved popular with art lovers; the paintings drew admirers at the gallery and sold well to collectors.

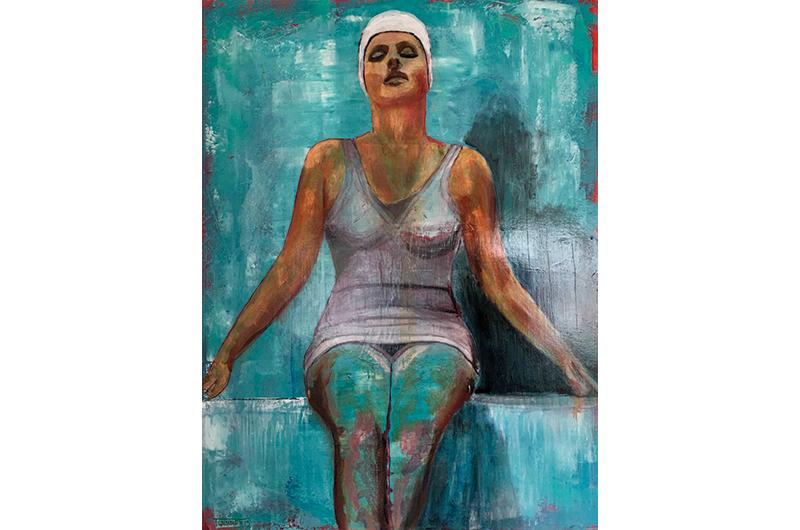

Over the winter, Crimmen began preparing for his 2022 exhibit at the Granary. He has been working from images and phrases in vintage advertisements found in National Geographic magazines owned by his friend and fellow artist Traeger di Pietro. He has been particularly intrigued by a series of ads for wool bathing suits from the late 1940s. “The ads reads that the bathing suits were 100% wool and priced from $1.49 to $2.69. I thought ‘Wow, that sounds comfortable,’” the artist explained with laughter. The exhibit will open on July 17, and Crimmen’s new paintings will be shown along with work by Steve Datz and VanLandingham.

Despite the commissions, exhibits, the camaraderie, the rounds made of gallery openings, and the hours spent painting in his shed/studio, Crimmen bristles at being called an artist. “Artist is a very strong word. I’m a painter. I paint stuff,” he said assertively. “I don’t know what kind of artist I am. I didn’t go to art college like a lot of my friends. But I’m more than happy to steal every idea they have. And I’ll tell them so.”