In 1955 our family spent its first summer on Martha’s Vineyard, renting a tiny house on Dukes County Avenue in Oak Bluffs, next door to the home of an older man our folks called “Chief of the Tribe – and leave him ALONE!”

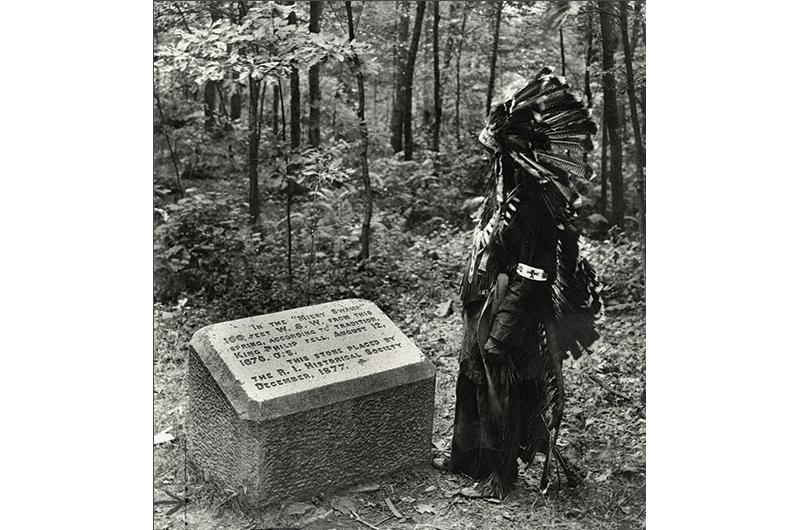

It’s only in magical places like Oak Bluffs that a child might find himself neighbors with a real Indian chief, let alone one who would don his feathered headdress when the folks weren’t around. Or even when they were around – the chief, seated in his white wicker rocking chair on the porch, would turn mischievous behind their backs and trade his normally dour expression for funny faces to make us children laugh. Not comprehending the lack of appropriateness then, I’d give him a palm-up greeting copied from television coupled with a solemn “How,” which was always met with two palms out, an “I don’t know,” a tilted head, a smile, and a wave.

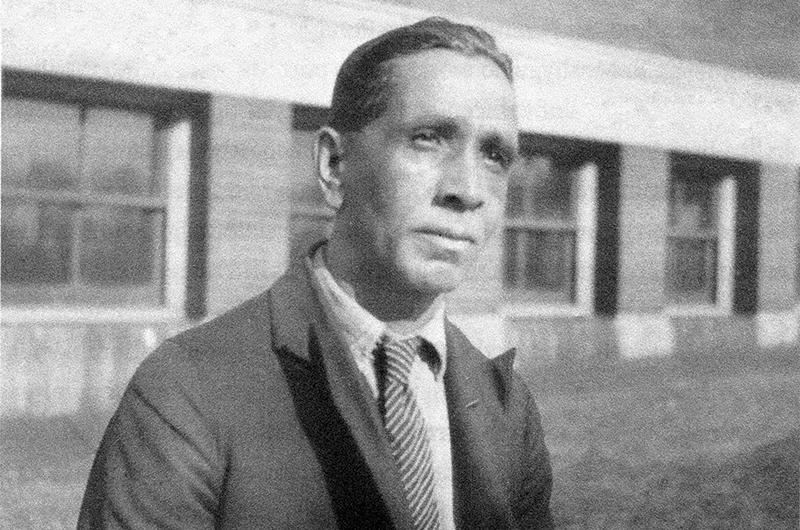

These were cherished memories indeed for a seven-year-old whose return to school at summer’s end would be marked by bragging about his friend the Indian chief. What I didn’t know then was that my neighbor LeRoy Perry was not just “Chief of the Tribe – and leave him alone.” He was Ousamequin, which means Yellow Feather, the first to hold the title of Massasoit, or supreme sachem, of the various bands of the Wampanoag nation in more than 250 years.

It was a position most famously held some ten generations earlier by one of his direct ancestors, who was also known as Ousamequin. Massasoit Ousamequin, of course, was the Wampanoag leader who made a fateful alliance with the Pilgrims at Manomet (Plymouth) in 1621. Following Massasoit Ousamequin’s death, and the death of his elder son Wamsutta, the position eventually passed to his younger son Metacomet. Metacomet tried to continue his father’s policy of alliance with the English colonizers, even taking the name King Philip, in part to show his faith in their friendship. By the 1670s, however, it had become obvious that the colonizers had no interest in abiding by previous agreements with the Native Americans, or in otherwise limiting their expansion. Metacomet led the bloody regional uprising that spread throughout New England and became known to history as King Philip’s War.

The outcome of King Philip’s War was not inevitable by any means; it was arguably the most successful Native American uprising in history. But the English ultimately prevailed, and Metacomet was assassinated by a fellow Wampanoag. The descendants of the Pilgrims that his father had helped survive displayed Metacomet’s severed head on a pike at the entrance to Plymouth colony for the next twenty-five years. His wife and most of his children were sold off as slaves to Bermuda.

In the wake of the war, the various Wampanoag communities of southeastern New England were left politically powerless, increasingly landless, and without any unified leadership. The Wampanoag of the Vineyard, or Noepe, did not actively participate in the war of resistance and were somewhat shielded from the immediate impact of the English retribution. But not entirely. Wampanoag everywhere were weakened by the nation’s destruction and dispersal. The People of the First Light, as they call themselves, had no supreme sachem. But the Wampanoag were never gone. And they never forgot who they were.

LeRoy C. Perry was born in Tiverton, Rhode Island, in 1874. His father, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, was a Black man originally from North Carolina who had made his way north in time to serve during the Civil War as a private in the famed 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. He married Rachel E. M. Crank, a Wampanoag, and it is through her that Perry traced his roots back to Massasoit. Rachel and Commodore raised Perry, his twin brother Royal, and younger brother Theodore in Fall River’s “Indian Town,” but relocated to Fall River proper after the family home burned in a fire. They were lean times, made more so by the usual and endemic racism toward anyone who wasn’t white. Rachel worked as a domestic, while ten-year-old Perry went to work at the Weetamoe textile mill and later took a position as the custodian at Calhoun Avenue School.

When he was about twenty, Perry felt the call to enter the ministry, but was told his sixth-grade education was inadequate. Undeterred, he began to study on his own, and when one of the masters at school where he worked found him after hours teaching himself Greek, German, French, and Latin, he offered to assist with his learning. Perry stayed at the school for another eight years, allowing him to continue an education that led eventually to Sunday school teaching, a role as exhorter, elder, deacon, and as a Methodist preacher. Perry practiced his religion as a minister to the Narragansett Indian Church in Charlestown, Rhode Island, and as pastor of the Indian Church in Westerly, Rhode Island.

During those years he also felt the call of love, marrying Sarah Collins in 1896, who died of tuberculosis when their two children, Nada and Earle, were still toddlers. He remarried in 1901 to Hattie Gross, who died in 1907 giving birth to their daughter, Kathitha (Hazel). Now with three young children, he remarried again in 1908 to Susie Gladding, who was six years his senior. Life at last appears to have settled down. By 1939 the couple were able to purchase a home on Dukes County Avenue in Oak Bluffs. The house, which is still standing, is across the street from the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association (MVCMA) and not far from the largely Black neighborhood that resulted from the MVCMA’s policy at the end of the nineteenth century to grant leases to persons of color only for lots located at the extreme north and west limits of the association grounds.

It’s not possible to know what drew Perry and his family to Oak Bluffs – the Wampanoag history of the Island, the town’s unusual openness to persons of color, its origins as a religious revival. Or all of the above. But fittingly, the couple bought the house from Bertha and Hezikiah Madison, the latter a Native American. It was sold in 1961 after Perry’s death to George Tankard, the scion of the well-known African American Tankard family on the Island.

While serving various congregations in Providence and preaching in the summer occasionally at Bradley Memorial Church in Oak Bluffs, Perry became increasingly interested in his Wampanoag heritage. In particular, he focused on learning the Algonquin language, studying Native American handicrafts, and attempting to enumerate the remaining Wampanoag. “I am very nearly the last of the Wampanoags of straight stock,” he remarked to an interviewer in 1927. It’s an interesting comment, given that his father was African American, one that perhaps reflects the matrilinear nature of tribal identity in many Native American cultures. Further confusing matters, the 1940 census lists his race as: “White [Indian (Native American)].”

He wasn’t alone in his pursuit of his heritage. During the 1920s, around the time of the 300th anniversary of the arrival of the English in their land, he and other leaders of various Wampanoag and related groups from Gay Head, Fall River, Mashpee, Dartmouth, and other locations around southeastern New England began to rebuild their national identity. He joined, and may have been involved in founding, the Algonquian Indian Association, which was dedicated to preserving the culture of the eastern tribes generally and the Wampanoag in particular. Over two days of meetings in 1928, they elected him over several other candidates to become both chief of the Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe and the supreme sachem, or Massasoit, of the wider Wampanoag nation.

His connections to the Vineyard grew after his election. In 1930 he presided over the first Gay Head powwow of the modern era, and in 1933 he became the pastor of the Gay Head Baptist Church. Established in 1693, it is the oldest Native American church in continual use in America. In October of that year, a profile in the Vineyard Gazette described him: “Self-educated, he has arisen from a lowly position to become an ordained minister of the Gospel and for a number of years has devoted his efforts to the improvement of conditions of Eastern Indians. Chief of the Wampanoags by election, his Indian name is Yellow Feather, and he is thoroughly versed in the old Indian language, traditions and tribal customs. It was Mr. Perry who laid the foundation for the formal organization of the present Gay Head tribe and others in this section of the country.”

Over the following decades Perry rarely turned down the opportunity to travel and speak – at schools, YMCAs, men’s clubs, powwows – about Wampanoag culture and the injustices faced by Native Americans across the country. “He was,” according to a Newport newspaper, “an outspoken champion of the rights of the American Indian, and a critic of conditions under which some of them lived on reservations.”

Though his own life was marked by tragedy – on New Year’s Eve of 1945, his wife Susie died at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital after a tragic fire at their home – he remarried and carried on in his mission of educating and advocating into his eighties. Looking back, even his cheerful “I don’t know” in response to a young Black neighbor’s solemn palm-raised “How” seems like a gentle refusal to submit to the common stereotypes of the day.

On Saturday, June 25, 1960, Perry died at age eighty-six at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, where he had been a patient since May of that year. Absent a little homework to locate Lot 81 on what is called Hemlock Avenue in Oak Bluffs’s Oak Grove Cemetery, you will likely not come across the plots where he and his third wife, Susie F. Perry, are interred, because there are no markers to indicate the burial of a Native American chief who was a direct descendant of the man who welcomed the Pilgrims to the land they ultimately stole.

But the elaborateness – or lack thereof – of a marker doesn’t always translate to the value of a life that may have been remarkable, like that of the Rev. LeRoy C. Perry; Ousamequin (Yellow Feather), chief of the Wampanoag from 1928 to 1960. Though he didn’t live to see it, thanks in part to groundwork laid by him and his generation of leaders, the federal government officially recognized the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) in 1987 and the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe in 2007.

Not too many years before he died, around the same period I as a youngster was warmed by an introduction with a smile and playful headdress from my older friend the “real” Indian chief, he wrote a letter to the Boston Herald.

“I am sorry that any group of so-called Americans assumes the right to classify the descendants of the ‘original aborigine’ called, unfortunately, by Christopher Columbus, ‘Indians,’” he wrote. “We are not and never were Indians. We, here, were Wampanoags...”

Looking back those seventy-some years now, I have learned to say in the Wôpanâak language he helped prevent from extinction, Kutaputush! Thank you, chief.

9 comments

9 comments

Comments (9)