Voice of America bulletin to eastern Europe, Tuesday, November 24, 1970:

“Dispatches from Massachusetts report that a crewman of a Soviet fishing mother ship tried to defect while the vessel was tied up alongside a US Coast Guard cutter off Martha’s Vineyard island. The reports say the Soviet seaman got aboard the cutter but was returned to his own ship at the request of the Soviet captain. Details about the incident remain unclear. Dispatches said American and Soviet officials were conferring . . . about fishing rights in the North Atlantic.”

10:00 a.m., Monday, November 23, 1970

Skies over Vineyard Sound this late-autumn morning are gray. The air is mild. The Sovetskaya Litva, 5oo feet long, lies at anchor one mile west of the entrance to Menemsha harbor. She serves as a refrigerator, factory, and mother ship to the Soviet-controlled Lithuanian fishing fleet. She carries 170 officers and crew.

The Vigilant, a medium-range Coast Guard cutter based in New Bedford, approaches the Sovetskaya Litva from astern. The cutter, 210 feet long, is designed for offshore fishing patrols and rescues. She carries 10 officers and 61 crewmen. Her master is Commander Ralph W. Eustis, a 1955 graduate of the United States Coast Guard Academy in New London and one of the most admired Coast Guard captains in New England. This November morning, his job is to ferry a delegation of five officials from the New Bedford fishing industry and the federal government to meet officers in charge of the Lithuanian fleet. There will be a daylong conference aboard the Litva regarding the methods by which the Soviets catch yellowtail flounder, a staple of the New Bedford fleet, rapidly vanishing from Georges Bank. In 1970, foreign fleets may fish as close as twelve miles from the US coastline, and the Litva has been operating east of Nantucket, on Georges Bank.

Commander Eustis has been skipper of the Vigilant for sixteen months. He expected to meet the Litva nearer her own fleet, somewhere off Noman’s Land, just south of Gay Head. He is thus surprised to see her anchored in Vineyard Sound. But the weather has been foul for several days, and he thinks the decision of the Soviet ship to come inshore is wise. It will be easier to transfer the American conferees in the lee of Menemsha Bight. At the invitation of the Soviet vessel, he moors alongside her, his port side to her starboard side. The Vineyard shoreline is close enough to see the windows in the summer houses at Lobsterville and Gay Head.

Soviet seamen and Coast Guard crewmen crowd the rails, shout greetings, and throw cigarettes, coins, and caps to one another. Commander Eustis and the American delegation are lifted from the helicopter deck of the Vigilant on an old tire suspended from a boom aboard the Litva. According to Day of Shame, a 1973 book by Algis Ruksenas on the events of this day, Eustis turns to Lieutenant Commander Paul E. Pakos, his second in command, before he is taken from the deck of his ship.

“No cross-visiting at this time, Paul,” he says. “We’ll see how things are later.”

10:30 a.m.

On the third deck of the Sovetskaya Litva, a man watches the Soviet and American crew members laugh and talk. He is forty years old, a native of the village of Griskabudis, Lithuania. His name is Simonas (Simas) Kudirka. He is the illegitimate son of a woman born in Brooklyn, where her own father had emigrated and worked in a foundry for nine years before returning to Griskabudis. As a boy, Simas Kudirka heard stories of the United States from his grandfather. Now he is seeing America and Americans up close for the first time in his life.

Like most of his fellow citizens, his life has been hard, his teenage years bisected by invasion and occupation, first by the Nazis, then by the Soviets. According to For Those Still at Sea, an autobiography written with Larry Eichel in 1978, Kudirka refused in 1948 to turn in his cousin, a guerilla fighting the Soviets from the woodlands around his village. To escape the sadness of the fate of his country, and to see something of the world his grandfather described to him in his boyhood, Kudirka joined the Lithuanian fishing fleet as a radio technician and operator. It is a good job, when he is allowed to do it, but the punishment for his refusal to inform on his cousin never ends. Mostly he is given toilets to clean, and he is refused papers and a passport to go ashore when the Litva is in port.

Kudirka looks down to the deck below him and sees two young crew members pick up glossy magazines tossed over the rail from the Vigilant. They hide them under their jackets and scurry below. Four feet away from Kudirka, the political officer of the Litva has also seen the crewmen run off with the magazines. Kudirka hears him say to another officer, “Those two will never go to sea again.” In his autobiography, Kudirka will write: “I heard those words and inside I blew up. They would be booked on voyages and then taken off at the last minute by border police without ever knowing why. They would always be threatened with the loss of their right to work. And for what? In the instant they picked up those magazines, their lives melted into mine and mine melted into meaninglessness. We were victims – all of us. We were trapped on a floating jail. . . . The idea of jumping to the American ship flashed into my mind out of nowhere.” Kudirka has a wife, Genele, and two small children, a girl named Lolita and a boy named Evaldas. “I would work hard,” he will later write of his thoughts at this moment aboard the Litva. “I would get my family out of the Soviet Union. It wouldn’t be easy – I knew that – but in three or four years I could do it. I could pull them out into freedom, and any wound I had caused would be healed.

“My mind was set. I was going to jump.”

11:00 a.m.

Aboard the Vigilant, Lieutenant Douglas Lundberg, the operations officer, is leaning against the rail on the bridge wing. Only a few feet separate him from the main deck of the Litva. He turns and sees a short, dark-haired, youthful man, built like a middleweight wrestler. The man looks at him across the space between the two ships. He says quietly, “I want political asylum.” Then he looks left and right, sees no one near, and murmurs, “Gestapo. Gestapo.”

Lundberg stares at the man for a moment. He turns and walks into the bridge, finds Paul Pakos, the second in command, and says, “Mr. Pakos, you aren’t going to believe this, but this guy says he wants political asylum.” Pakos and Lundberg go out to the bridge wing. Quietly the man tells the two officers, “I will check.” He goes below, then returns. “Not too cold,” he says. “I swim.” He mimes swimming with his hands. He disappears again.

Pakos orders a ladder hung from the starboard bow, hoping the Soviets cannot see it. He sends a man over to the Litva and asks Commander Eustis to return to the Vigilant. While he waits for the captain to come back, he sends a coded message to Coast Guard offices in downtown Boston. “Estimate with 80 percent probability” that a crewman will attempt to defect from the Litva to the Vigilant, it says. “Same man later indicated to Executive Off. that water not too cold and he would swim. . . . If escape undetected, plan to recall entire delegation under false pretenses and depart. If escape detected, foresee major problems if delegation still aboard. Req. advise.” The message is sent at 12:43 p.m.

Commander Eustis is lifted back to the Vigilant. Pakos tells him of the would-be defector. Eustis gets a look at the man, who is milling around on the main deck of the Litva. Eustis thinks that “any man who would make a decision like this in his own mind must be going to do it.” He tells his officers to do nothing to entice the man and to say nothing to the Vigilant’s crew. He returns to the Sovetskaya Litva so as not to arouse suspicion.

1:05 p.m.

Captain Fletcher W. Brown Jr., chief of staff of the Coast Guard First District, returns from lunch to his office in the John F. Kennedy Federal Building at Government Center in Boston. He is handed the coded message from the Vigilant, which has just come in. Captain Brown is generally aware that the United States accepts refugees and asylum seekers from Cuba, the Soviet Union, eastern Europe, and Vietnam, but the State Department has never sent Coast Guard headquarters in Washington specific instructions about what to do with a defector, and no guidelines have ever been given to the First District. “Thank God, at least we’ve got Eustis down there,” Captain Brown says.

As chief of staff, Brown is second in command of the First District. But for twenty days, he has been acting district commander. His boss, Rear Admiral William B. Ellis, is at home in Beverly, recovering from a hernia operation. First, Captain Brown calls Coast Guard headquarters in Washington with the news of a possible defection during the fishing conference on Vineyard Sound, and relays the secret message from the Vigilant. He is told to keep headquarters informed of developments. Then he calls Admiral Ellis at home for his counsel – just as he has on other First District matters, great and small, during the admiral’s convalescence.

“Mentally, he was at work, merely as a result of continued briefings,” Brown will later tell Algis Ruksenas, the author of Day of Shame. “What happened this day is merely an extension of exactly the same thing I did every single day – except this was a beaut. I felt obligated – it was essential – that I call him as my immediate, designated superior.” In November 1970, he regards Admiral Ellis as one of the wisest and finest officers he has known in a twenty-two-year Coast Guard career. But the admiral, a 1936 graduate of the Coast Guard Academy, is a man schooled only in the subjects of engineering and seamanship. He knows little of history or world affairs – still less of the record of Soviet behavior toward its unsuccessful asylum seekers.

Admiral Ellis tells his chief of staff that if the defector reaches Vigilant, the Soviets should be told. And if they want him back, they should have him.

“If we allowed the Vigilant to be used as a haven under that circumstance, if we went on this way,” the admiral will tell a Coast Guard board of investigation two weeks later, “we would never be able to have meaningful meetings again with these people.” But he has a more personal, visceral reaction to the news of a possible defection – one he never reveals to official investigators. To Ellis, the man is a maritime lawbreaker, a villain.

“He’s a deserter no matter what he is,” he will tell Ruksenas, the author, ten months later. “And I don’t think I thought about the political overtones. . . . If he did get aboard, we were going to have to – under any rules of decency – send him back. . . . I figured that if one of my men had deserted to a foreign ship, and I had been asked – invited – to go aboard and get him, I would have sent some people to get him. If this guy said he wasn’t coming back, I’d have dragged him back.”

Ellis speaks forcefully to Captain Brown about the Coast Guard obligation to return the man, but would insist forever after that he was only offering advice as a superior officer on leave. Yet Captain Brown senses the conviction in Admiral Ellis’s voice and hears something more: “I did not feel that I had any authority to refuse Admiral Ellis’s orders on that day,” he will testify to the board of investigation. If he receives different instructions from Coast Guard headquarters or the State Department later in the day, he knows he will overrule Ellis as acting district commander. But if he receives inadequate instruction, or no instruction at all, he will feel compelled to obey his admiral, off-duty though he may be. He will later tell Ruksenas that he realized that, from this moment forward, there was “no way to come out of this situation clean.”

1:15 p.m.

Many men, in offices located farther and farther from the drama playing out off Menemsha Bight, begin to make disinterested, narrow, bureaucratic decisions that will profoundly affect the life of Simas Kudirka, who has not yet made his leap to freedom.

In his call to headquarters in Washington, Captain Brown does not ask how to handle a defector once aboard, but focuses instead on that part of the Vigilant’s message suggesting the man may swim between the two vessels.

He asks Rear Admiral Robert E. Hammond, the chief operations officer at Washington headquarters, how much force the Coast Guard may use to retrieve a Soviet seaman in territorial waters if the Soviets are trying to pick him up too. Captain Brown regards an attempted defection in American waters as an extraordinary event, and expects Admiral Hammond, an old friend from the academy, to take charge of the case personally in Washington. But Hammond delegates the responsibility. He calls Captain Wallace C. Dahlgren, the chief of intelligence, into his office and tells him to get direction from the State Department. Dahlgren has been at his post for just six weeks and knows almost nothing of State Department organization. It takes him four phone calls over the course of an hour and forty-five minutes to reach the right foreign-service officer, familiarize him with the outline of the problem, and get guidance about whether the Coast Guard is actually permitted to rescue a man swimming in American waters at the end of November.

2:00 p.m.

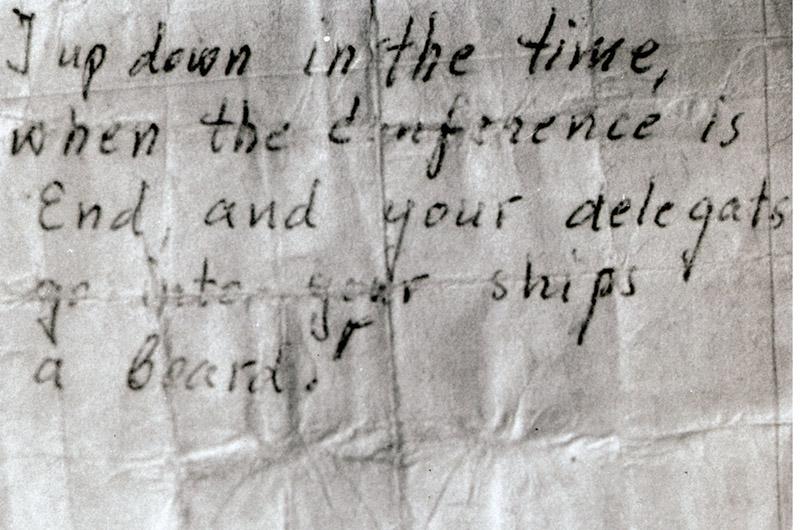

Aboard Vigilant, Lieutenant Lundberg is in the wheelhouse when the man appears opposite the bridge wing again. The man points to a small package in his hand. Lundberg goes to the end of the bridge wing. The man tosses the package. It barely clears the spray shield. Lundberg leans over the rail and catches it. It is a package of cigarettes. He says “Thanks” as nonchalantly as he can, removes a cigarette, lights it, and walks back inside the bridge. He feels something bulky in the bottom of the package. He tears at the cellophane. It is a note: “My dear comrade,” it says on one side, “I will up down of [jump from] russians ship and go with you together. If is a possible please give my signal. I keep a sharp lookout = Simas.” On the other side, it reads: “I up down in the time, when the conference is End, and your delegats go into your ships a board!”

For the second time that afternoon, Commander Eustis is recalled to his ship. The Vigilant has not yet heard back from the First District after sending its original message about a possible defection. Eustis orders a second message sent. It summarizes the note in the cigarette package and asks for a forty-four-foot lifeboat from the Menemsha Coast Guard station to stand by far off from the Vigilant, ready to sweep in and pick up a man in the water. The message is sent to Boston at 2:23 p.m., but the cryptographic machines aboard ship and at the First District do not work properly. It will take eight tries to get the message out. Boston does not receive it for another four hours and fifteen minutes. The forty-four-footer is never sent. Headquarters in Washington is never informed. The reason: by the time this new message reaches Boston, everyone in a position of authority will have gone home for the night.

Meantime, Kudirka goes below decks on the Litva, certain he has made himself clear. The Americans will be ready to receive and protect him after he jumps.

3:30 p.m.

Edward L. Killham, serving his third tour of duty in charge of bilateral matters in the office of Soviet Union affairs at the State Department, speaks with Captain Dahlgren, the intelligence officer at Coast Guard headquarters. He has read the Vigilant’s original message. Two hours have passed since the First District asked headquarters the procedural question about how hard it may compete with the Soviets to recover an asylum seeker from American waters.

Killham does not address this question immediately. To him, the obviousness of the overture – so public – is his first concern. It makes him think that the defection might be fake, a provocation designed to embarrass the United States on home waters. Killham knows that even if the defector is sincere, more than half of all asylum-seekers change their minds and go back within seventy-two hours. There is no point involving lawyers and superiors in this case while matters remain so hypothetical.

Killham answers the technical question Dahlgren relays about retrieving a defector from the water. He says that the Coast Guard ought to treat it as a regular search-and-rescue operation: “Don’t encourage him, but if he jumps in the water, you guys make a living of fishing people out of the water. You ought to beat the Soviets to him. Get him out and call us and we’ll decide what to do then.”

He does not make the larger point that the Coast Guard should, of course, hold on to the defector until notified otherwise. “I did not specifically discuss it with Captain Dahlgren,” he will tell the Coast Guard board of investigation, “because it seemed to me inconceivable that once a man had sought asylum on an American vessel that he could be returned. . . . However, in hindsight I might say that [I] was not imaginative enough. As I said, I couldn’t imagine that this thing could be permitted to develop the way . . . it did. In fact, I still find it hard to believe.”

4:30 p.m.

As darkness falls on Vineyard Sound, Simas Kudirka looks up and down the main deck of the Litva. He sees no one. He climbs over the railing. Then he jumps – probably close to ten feet – clearing the rail of the Vigilant. He lands beneath the portside lifeboat, rolls under it, then goes through a hatch, up a flight of stairs – and runs into Ivan Burkal, the acting commander of his own fishing fleet.

The conference is over, and the Americans are back aboard the Vigilant. Burkal is touring the cutter with two other Soviet officers. “Kudirka! What are you doing here?” Burkal says. “Excuse me, I don’t have time,” Kudirka says. He keeps going up the stairs and runs into the bridge. He sees Lundberg and says hello. The men in the wheelhouse are startled to see the man on their own ship. No one has seen him jump. They cheer, shake his hand, clap him on the back. Lundberg moves Kudirka down one deck to the watchstander’s head, a small bathroom with a toilet and wash basin. Lundberg goes to the captain’s cabin. “He’s aboard,” he tells Commander Eustis.

“Who?” asks Eustis.

“The defector,” says Lundberg.

Eustis goes down to the watchstander’s head. Kudirka is trembling. He throws his arms around the skipper. “Oh, captain, thank you!” he cries. Eustis will tell the board of investigation that Kudirka, in those first moments aboard the Vigilant, appeared to have put his whole life behind him. “It was the moment at hand that was [his] concern,” Eustis says. More than anything, Eustis now wants to send the three Soviet officers – the fleet commander, the political officer, and a Soviet translator – back to the Litva. He will then inform Boston, cast off from the Soviet ship, move away, and wait for instructions to come back from the State Department, via headquarters. Eustis goes to the bridge and looks down on the helicopter deck. The three Soviet officers stand there talking with one another. Instead of going back, they walk forward to his cabin and sit on a sofa, facing the American delegation, and say nothing.

4:35 p.m.

Five minutes after Kudirka jumps, Captain Brown, acting commander at the First District, gets permission from headquarters to go home for the night. It is dark and rainy in Boston. He reasons that if the man were going to leap into the water, he would have done so by the end of what, for Brown, is a normal working day.

He walks in the door of his home in Gloucester at 6 p.m. His wife tells him that there is an urgent message from the First District office. He doesn’t even remove his overcoat. He knows what the message will be. He calls Lieutenant Kenneth N. Ryan, the rescue coordination officer in Boston, and is told the defector is aboard. Commander Eustis – looking for guidance, finding no one who can help him in the Boston office, and unaware that Admiral Ellis is on leave – has called Ellis at home. The admiral has told Eustis what he told Brown earlier in the afternoon: the Soviets should be notified, and if they want him back, the defector should be returned.

Surprised by Ellis’s orders, Eustis has gone to the watchstander’s head. He has spoken with the defector for half an hour. Kudirka has given Eustis a packet of papers and small photographs of himself and his wife. “How could a man leave his family and his whole life so completely, as he would have to do?” Eustis will later ask Ruksenas, the author. “I was very impressed with him, that he had made a decision like this. . . .” With a sense of sadness, Eustis gives Kudirka the news that he must be returned. “No give me back!” Kudirka cries. “No give me back! They kill me! My life no good over there!”

Now Captain Brown speaks with Eustis via a public radiotelephone link. Hoping to navigate around Admiral Ellis, Brown advises Eustis to try to persuade the Soviet officers in his cabin to leave, in return for a promise that the Vigilant will not depart with the defector unless ordered to do so from Washington. “This is a matter that will have to be resolved by the State Department,” he tells Commander Eustis, who signs off.

Ryan, at the First District, now asks Captain Brown whether he should call headquarters in Washington with the news that the defection has occurred. Word will then be passed to the State Department, which will give guidance. “No. Hold on a minute,” says Brown. “I’ll get back to you shortly.” Once again he calls Admiral Ellis for advice.

5:30 p.m. – 8 p.m.

Kudirka sits in the watchstander’s head, his arms around his knees, feeling numb, wondering if he has somehow violated the rules of defection. “What was happening out there, beyond the door of this toilet,” he will write in his autobiography, “where men I could not see were debating my fate in a language I could not understand?”

During the course of the evening, Captain Brown speaks with Admiral Ellis three times. Ellis dismisses the idea that headquarters or the State Department

will offer any better guidance than they already have – that the Coast Guard may indeed rescue a man who jumps in the water. He also scoffs at the idea that the man has any reason to fear for his life. The Soviets “are not barbarians,” he tells his chief of staff. To the board of investigation, he will later say: “I think that any man in that circumstance would plead for his life.

I didn’t, and I still don’t, feel there [are] any facts that the Russians go around killing people.”

Aboard the Vigilant, Commander Eustis speaks with Brown four times that night. With each call, he hears Brown’s views harden, and his own options as master of the Vigilant diminish. The American conferees, aware now of the defection, are sharing a cabin with the three sullen Soviet officers, who refuse to leave. The Americans insist to Eustis and the Russians that this is a matter for the State Department to resolve. But the foreign policy of the United States no longer seems to be a part of Brown’s thinking, and Eustis doesn’t feel he can ask Brown whether the State Department has given instructions without appearing to question his orders.

At 8 p.m., the Soviet political officer hands Commander Eustis a note, sent from his ship. The Litva has overheard the radiotelephone conversations spelling out the instructions from Admiral Ellis that the Soviets must be officially notified of the defection, and formally request Kudirka’s return. The note declares that Kudirka has broken into the captain’s safe, stolen 3,000 rubles, and is now hiding aboard the American ship. The Soviets want him back. No one searches the defector for the money. No one sees that a charge of thievery gives the Coast Guard a new opportunity to take Kudirka ashore, with any willing accuser, on the pretext of filing a criminal complaint with the police, a district attorney, or a representative of the United States government – perhaps the State Department or Immigration and Naturalization.

“I had the formal note. I knew now that I must return him,” Eustis will tell the board of investigation. He goes to the watchstander’s head to speak with Kudirka. Kudirka despairs. He cannot understand why asylum is not being granted, and why the Americans do not understand the danger he is in. “Dear Captain, please not giving me again, again,” Kudirka pleads. “For me is Siberia. Siberia is death.”

8:24 p.m.

In Boston, Lieutenant Ryan is busy handling radiotelephone calls between the Vigilant and Captain Brown. He finally gets a few minutes to inform headquarters in Washington of the defection and the Soviet note requesting that the sailor be returned, which he learns of while listening in to a conversation between Commander Eustis and Captain Brown. He tells the duty officer at headquarters that the man “is being returned” at the written request of the Soviet master.

The duty officer at headquarters calls Admiral Hammond, the chief of operations, at home and tells him “the case has been resolved” with the return of the defector – which has not yet actually occurred. Admiral Hammond will say later: “I thought what had happened was that he had come aboard [and] either the ship or the district had urged him to go back and not cause an incident between the two vessels on a fisheries conference, and that the man had either agreed to go back or had been led back. I just felt that he had gone back really of his own free will. Practically so.”

The duty officer at headquarters now calls the State Department. Four hours have passed since Kudirka’s jump. The news of the defection and the return reaches Edward A. Mainland at home. Mainland is an assistant to Edward Killham, the Soviet bilateral affairs specialist at the State Department, who had left work at 7 p.m., assured by Captain Dahlgren at headquarters that a defection will not occur after night falls in southeastern New England. Mainland is perplexed by the news of the return – he will place a call of his own to Coast Guard headquarters three hours later to check again what few facts headquarters has – but he does not try to stop what might still be happening on or between the two ships. And he does not call Killham, his boss, with a report.

Killham will not find out about what is still to transpire on the decks of the Vigilant until he returns to work the next day. “I spent most of the morning trying to find out what had happened,” he will tell the board of investigation. “And everything I found out kept getting worse and worse.”

8:50 p.m.

The Soviet officers want Eustis to order his own men to force Kudirka back to the Litva. Eustis insists that the Russians do it themselves. “I thought he was a guy that was in fear of his life, and he was going to put up an awful struggle either way,” Ralph Eustis will say later. “I just felt that if somebody had to use that much force to subdue somebody, let them do it. Why make my guys do it?”

The Soviets seem reluctant. In this hesitation, Eustis sees a last chance to save Kudirka. At 10:14 p.m. he places a final call to Captain Brown at his home. The skipper says that the Soviets do not want to force their own man off the Vigilant. Eustis starts to suggest that he order the Russian officers back to the Litva. He will then transport Kudirka to New Bedford and let the State Department take it from there. Captain Brown cuts him off. “Commander Eustis, you have your orders, you have no discretion,” he declares. “Use whatever force is necessary.” Never before has Captain Brown given him so direct and forceful an order. Dismayed, Eustis goes to the Soviet officers. “He’s all yours,” he says.

“When I hung up the phone, why, well, I guess I totally broke down in this house with my wife,” Captain Brown will tell Ruksenas many months later. “And I can just see it right now. I told my wife – I said: ‘I spent all my life saving people, and I finally had to give an order, and I think it’s for a man to be killed.’”

10:30 p.m. – 11:50 p.m.

With the three Soviet officers, three additional crewmen from the Litva force their way into the watchstander’s head. They hit Kudirka and kick him, driving him to the floor. He breaks free and runs down a passageway to the door of the captain’s cabin. The door is open. “Help me! Oh, God, help me!” he cries to the Americans inside. The Russians grab him. He clutches the doorknob. They pull, striking his arms and hands. Robert Brieze, a Latvian refugee who escaped his country, sailed to Boston in 1944, and is now president of the New Bedford Seafood Producers Association, leaps to his feet and tries to push the Soviets away. “No, no, you cannot do this!” he yells. But he is pulled back by William Gordon, head of the delegation, who tells him matters have gone too far to stop. The Soviets close the door on Kudirka’s hands. But the Russians lose their grip, and Kudirka flies out the portside hatch, where he tumbles under the same lifeboat he’d landed under six hours earlier. He crawls under the railing and rolls over the side. Lundberg, the lieutenant to whom Kudirka had tossed his note in the cigarette pack early in the afternoon, is standing near the lifeboat. He sees the defector’s fingertips clutch the lip of the deck for a moment. Then the fingers let go. “Man overboard!” Lundberg cries. Life jackets are dropped into the narrow space between the Vigilant and the Sovetskaya Litva. On the bridge, Paul Pakos shines the port signal lamp down on the water between the two ships. Commander Eustis orders his men to unmoor the cutter, cutting the lines with axes if necessary. He orders his vessel to back away from the Litva to avoid crushing the man. The turbines rumble.

But from the lip of the deck, Kudirka has swung himself onto a covered deck below. From the Litva, his fellow sailors see him run toward the stern of the Vigilant. They run along the deck of the mother ship, shouting to the Soviet officers and crewmen in pursuit that the escapee is one deck below them, heading aft.

On the fantail, Joseph Jabour, commissaryman third class, is wearing a telephone apparatus on his chest. He is temporarily assigned the duty to call the bridge when the stern lines are cast off. Kudirka, shirtless, runs toward him, climbs the .50 caliber gun mount on the fantail, and tries to go over the

side. Jabour and a boatswain’s mate grab his wrists. Kudirka speaks to them gently, trying to tell them a boat is supposed to be waiting for him out there in the darkness. But the Russians come running across the deck, leap onto the backs of the Americans, and haul Kudirka back onto the fantail. One tries to snare the wire on Jabour’s telephone to choke Kudirka. Jabour pulls it back. Kudirka “was screaming,” one of the Americans will tell the board of investigation. “I don’t know what he was saying. It was in Russian. He made screaming sounds of pain.”

The Russians drag Kudirka feet first to the ladder up to the helicopter deck. One has Kudirka in a headlock and cracks his head into the stanchions of the ladder as they climb it. Jabour knows orders have been passed not to get involved, but he does not know from whom they came. He does not use his telephone to call the bridge about the beating he witnesses.

The Soviets, carrying blankets and a rope, tie Kudirka to a lifeboat winch. As the Vigilant begins to back away from the Litva, at least two mooring lines snap. The Litva’s cargo boom tears away several antennas and a signal light atop the bridge of the Vigilant. As the Vigilant backs away, a Soviet sailor notices the movement. He wraps a line around Kudirka’s neck and tries to throw it to his mother ship. Ensign John Hughes, gunnery officer aboard the Vigilant, runs up to the bridge and says the Soviet sailors are beating and trying to strangle the defector. Pakos orders him to stop it if he can. Hughes returns to the flight deck and unwraps the line from around Kudirka’s neck. He orders the Soviets to stop hitting their captive.

Kudirka, bound in the blanket, is hauled into a tool shack on the helicopter deck. The crewmen hit him again. When the Vigilant stops, they carry him from the shack to the cutter’s lifeboat, which has been lowered to the level of the helicopter deck.

Commander Eustis comes down from the bridge. He sees Kudirka tied in the blanket from feet to neck, lying on the deck. Kudirka is conscious. He looks up at Eustis as the captain approaches him, but to Eustis, his eyes appear blank, at least at first. Eustis will tell the board of investigation, “I approached this man, tried to speak to him and indicated that I was sorry for what was going to happen to him, and was personally, as a man, concerned for him. He said nothing to me at the time, but he did indicate he knew who I was and attempted to let me know, ‘That’s the way it was.’” It is 11:30 p.m.

Kudirka, still bound, is dropped two or three feet into the Vigilant’s lifeboat, landing head first on the engine hatch. The boat, manned by Vigilant sailors and filled with the Soviet assailants, motors a mile across Vineyard Sound with one Russian sitting on Kudirka’s head, another occasionally chopping at his neck and body with the knife-edge of his hands. It is unclear whether Kudirka is conscious. “If he is not dead now,” the Soviet political officer tells the Americans, “he will be dead in a few minutes.”

At the Sovetskaya Litva, the tire is lowered and Kudirka is hauled onto it. The Soviets climb on top of him, and the crew is raised to the deck of the mother ship. The Soviet captain sends down a bottle of Scotch, a gift for Commander Eustis.

It is a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red Label. To this day, the skipper of the Vigilant cannot remember what he did with it.

Aftermath

A brief story about the attempted defection in Vineyard Sound appears the next morning in the New Bedford Standard-Times. It is picked up by the wire services. Lithuanian Americans protest in Boston, Washington, and Cleveland. The story makes the front pages of The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune. The Washington Post says in an editorial: “No more sickening and humiliating an episode in international relations has taken place within memory than the American government’s knowing return of a would-be Soviet defector to Soviet authorities on an American ship in American waters . . . . [T]he heart clogs in contemplation of this fantastic parable of our times.”

President Richard M. Nixon declares himself outraged by the return of the defector. He orders an investigation at the State Department. Guidelines on defection cases are swiftly handed down to Coast Guard headquarters and passed to all Coast Guard districts: no defector is to be returned without specific instructions from the State Department. A subcommittee of the House of Representatives holds hearings. At the conclusion of the Coast Guard investigation, Admiral Ellis and Captain Brown are forced into retirement. They will remain friends, play bridge weekly with their wives, and attend Coast Guard functions together. But they will never again discuss the incident. Captain Brown dies in Easton, Maryland, in 1981 at the age of sixty-one, Admiral Ellis in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, in 2001 at the age of eighty-seven.

For permitting foreign nationals to use force on a Coast Guard vessel, Commander Eustis loses his command of the Vigilant and is reassigned to shore duty as second in command at Governor’s Island, New York, the largest Coast Guard base in the world. Passed over for promotion to captain, he will retire from the Coast Guard in 1975. He will spend the next twenty-three years in business, much of it working with the Department of Defense on antisubmarine warfare matters. Today he lives in Mattapoisett with his wife Merry. This year, he is the co-chairman of the fiftieth reunion of his class at the Coast Guard Academy in New London.

Protesters gather at the State Department, demanding the head of Ed Killham, the Soviet specialist, for telling the Coast Guard that it could fish a defector from the water, but failing to add that it should keep him afterward. He is quickly transferred to the diplomatic wilderness of Copenhagen. In 1976 he is invited to work as a Soviet expert at the Strategic Arms Reduction talks in Geneva. He is appointed deputy chief of missions, the number two man, at the American embassy in Brussels, and retires as the head of the State Department’s office of Central African Affairs in 1987. With his wife Lucy, he now lives in Georgetown, where he is working on a book about the nineteenth-century Russian statesman Mikhail Speransky.

Fate of Simas Kudirka

Simas Kudirka is sent first to the Potma prison in the province of Moldova, 225 miles southeast of Moscow. There he engages in a series of protests, hunger strikes, work stoppages, and attempts to alert the West to conditions in Soviet prisons. For his transgressions, he is sent to Camp No. 36, Special Correctional Work Institution, in the Perm region. In winter, on early mornings, the temperature falls to 70 degrees below zero, and birds freeze to death in mid-air if they try to fly.

In September 1973, a Lithuanian émigré living in New York learns that Kudirka’s mother had been born in the United States and that the defector, born out of wedlock, might be able to claim American citizenship. The State Department takes up the case and requests Kudirka’s release. At first the Soviets balk. But senators and congressmen demand his return, and Henry Kissinger intervenes personally with the Soviet embassy and the Soviet leadership. On August 23, 1974, Kudirka is taken from prison and granted citizenship at the US embassy in Moscow. With his family, he flies out of the Soviet Union on November 5, 1974. He settles first in Brooklyn, the place of his mother’s birth, where he becomes a janitor. Eventually he moves to Los Angeles, where he manages a building in Santa Monica. In 2002, he returns to live in a liberated Lithuania, the land from which he tried to escape thirty-five years ago, finding instead seven hours of freedom in the watchstander’s head of a Coast Guard cutter named Vigilant, moored one mile west of the shoreline of Menemsha Bight.

6 comments

6 comments

Comments (6)