Seventy-three years ago, Ralph W. Dexter, a biology professor from Kent State University in Ohio, traveled to Martha’s Vineyard in August to survey eelgrass beds in Menemsha Pond. His boat guide was Linus Jeffers of Gay Head (now Aquinnah), a member of the Wampanoag Tribe who, according to Dexter, “had made observations on eelgrass in that body of water while engaged in fishing for quahogs and scallops.”

In his report, Dexter noted that he identified among the eelgrass meadows various shellfish: gem shells, scallops, mussels, and various periwinkles. The seemingly healthy beds were a welcome sight to the professor, though he reported that Jeffers remembered an earlier time when the eelgrass was far more abundant, so much so that it “choked the marginal waters of the pond to the extent that it was extremely difficult to force a boat through the water.”

Indeed, eelgrass was once so common it was widely used for a variety of purposes along the East Coast by Native American cultures and early European arrivals. As recently as the early 1900s eelgrass was collected from intertidal zones with a scythe for use as packing material, mattress stuffing, bedding for domestic animals, insulation for homes, and compost for fertilizer.

But over the intervening decades since Dexter’s visit, the once-lush meadows of eelgrass – their long, slender blades swaying in unison to the rhythm of the tidal currents – have dramatically shrunk even further in size, leaving areas of Martha’s Vineyard’s bays, salt ponds, and harbors bare of marine vegetation. The absence of sheltering seagrass leaves valued marine species, including the delicate bay scallop and once abundant winter flounder, easy prey at their earliest stage of life.

“These habitats support many commercial species,” said Phil Colarusso, a marine biologist in the Coastal and Ocean Protection Section of the New England office of the Environmental Protection Agency who has been studying eelgrass for almost three decades. What’s more, he said, “if you’re worried about sea level rise, these habitats sequester carbon, so they’re taking carbon out of the environment that would otherwise go into the atmosphere and further perpetuate climate change.”

Eelgrass (Zostera marina) is just one of many varieties of seagrass around the world that are a vital part of the marine environment. But according to the best estimates, globally around two football fields of seagrass are disappearing every hour. Among the culprits are disease, coastal development, and poor water quality. The loss, mostly hidden from view – unseen and unnoticed except by fishermen, boaters, and researchers – affects the health of recreational and commercial fisheries and migratory waterfowl worldwide.

Eelgrass is used by scientists as an indicator species. Blades of eelgrass waving in the currents like a field of wheat in a breeze is evidence that water quality in that location is good. It’s also beautiful. Colarusso, a veteran diver, said the Cape and Islands’ protected coves and sandy shallows provide opportunities for people to see eelgrass beds on their own. “You really need to experience it yourself to appreciate it,” he said.

So what happened? In 1931 and 1932 a wasting disease of then-unknown origin struck eelgrass beds in higher salinity areas along the Atlantic coasts of North America and Europe. The result was “catastrophic,” Lisa K. Muehlstein, a University of Georgia researcher, wrote in a 1989 paper on the subject. The first signs of a problem were reports of declines in waterfowl populations in Nova Scotia in 1932, which at first no one connected to seagrass. “Subsequent reports of the extreme devastation of eelgrass populations in North America and Europe were soon to follow,” Muehlstein wrote, and within just a few years more than 90 percent of the eelgrass populations disappeared, “resulting in dramatic changes within the coastal ecosystem.”

Brant, a species of goose commonly seen in Oak Bluffs’ Ocean Park in the winter months, relies on a diet of eelgrass. According to Muehlstein, in 1934 it was estimated that “probably not more than 20% of the east coast brant populations survived the disappearance of eelgrass.” And it wasn’t only waterfowl. Clams, lobsters, crabs, scallops, cod, and flounder also noticeably declined.

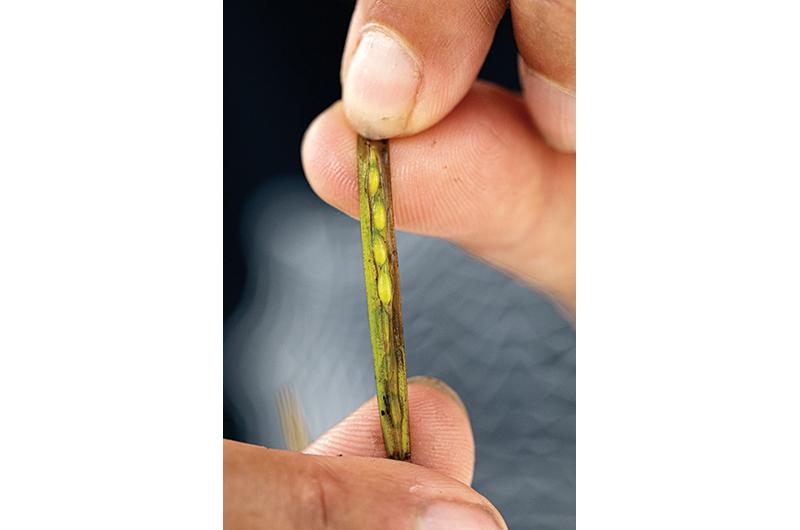

For years, the exact cause of the disease remained a mystery. At various points in time researchers suggested that bacteria, fungi, crude oil waste from ships, water temperature, and even phases of the moon were responsible. There is now general agreement that the culprit was Labyrinthula, a type of marine slime mold, and that the disease was spread by leaf-to-leaf contact. The symptoms begin with small dark spots and streaks on the blades of grass that grow larger and ultimately interfere with photosynthesis, leading to the death of the plant.

In the decades that followed the wasting disease of 1931–32, eelgrass beds began to recover. By the early 1950s, they had almost completely returned in most areas. Over the years eelgrass wasting disease has recurred periodically, but not to the extent seen in the 1930s. According to Colarusso, the disease is present in all meadows, but why it triggers a pandemic, per se, is still a mystery. Unfortunately, even in the absence of disease the overall picture of eelgrass health is not good. “I’ve been sampling out on the Vineyard since the early to mid-nineties, and some of the populations in the coastal ponds have declined dramatically,” Colarusso said.

Beginning in 1994 and continuing in stages until 2013, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) mapped seagrass beds in forty-six embayments along the coast of Massachusetts, including fifteen sites on Martha’s Vineyard. The results are sobering. In 1995, the DEP found 1,067.8 acres of eelgrass in Cape Pogue, which declined by 2001 to 512.2 acres, a 52 percent loss. By 2013 it was down to 480.19 acres of eelgrass. Menemsha Pond appears to have maintained a healthy set of eelgrass, though it declined by nearly a quarter, from 428 to 322.55 acres by the end of the survey period. A bleak report from Sengekontacket Pond, which could ill afford a drop, revealed that its 46.7 acres of eelgrass had been reduced to 28.82 acres, while West Chop went from 164.9 acres of eelgrass in 1995 to 11.46.

The results for Lagoon Pond were equally dismal: 178.5 acres in 1995 had been reduced to 65.31 acres in the 2010–13 report. According to Colarusso, vegetation is now almost completely absent in the pond. One factor was the construction of the new Lagoon Pond drawbridge, which led to the deposit of sand over an eelgrass meadow inside the entrance of the Lagoon. “There’s still eelgrass growing outside of the pond and hopefully some seed source from that meadow will make its way back into the pond and start colonizing it,” he said.

But the drawbridge can’t explain the Island-wide decline. And while there is some evidence that wasting disease was a contributing factor in Sengekontacket, it’s likely that old scourge is not the leading culprit either. Or even that there is a single leading culprit. Emma Green-Beach, executive director of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, a nonprofit organization supported by the six Island towns and dedicated to the health and sustainability of the Island’s shellfishery, attributes the decline to multiple stressors – a rise in water temperature, algae blooms linked to nitrogen loading, water clarity, crabs, boating activities – any one of which can lead to a tipping point.

Eelgrass beds expand in one of two ways: by an expansion of the root system called rhizomes, which send up new shoots, and by the dispersal of seeds, which can float many miles before they settle to the soft seafloor and germinate to form a new plant. In order to survive and thrive, the plants need essentially two things: clean water and an undisturbed seafloor.

Water clarity is critical to the growth and health of eelgrass beds. The most persistent and important cause of degraded water quality on the Island is excess nitrogen, which leads to algae blooms and eutrophication, or a lack of dissolved oxygen. A hopeful sign, Colarusso said, is that coastal communities that have been able to reduce nitrogen loading, often through centralized sewering, have seen a resurgence of eelgrass beds. On the Vineyard, that would entail enhanced septic systems, expanded public sewage systems and, he said, “probably more effective, reducing the use of fertilizers on people’s homes and gardens, because those are a significant potential source of nitrogen.”

As for protecting the seafloor, anchoring boats is known to disturb eelgrass root structures and is prohibited in many areas where eelgrass is present. For instance, this year the Edgartown selectmen voted to restrict anchoring to a limited area of Cape Pogue. There is also a push to modify conventional boat moorings, which rely on a heavy chain attached to a weight, often a cement block or mushroom anchor. As the attached vessel pivots in the current and wind, its mooring chain drags across the seafloor bottom, scouring vegetation in a circular pattern and generating suspended sediment that can inhibit nearby grass.

In recent years there has been an effort to educate boaters and communities on the advantages of “conservation moorings,” which are common in the Florida Keys and elsewhere. These sometimes rely on a helical or screw anchor instead of a block, but most of the benefit comes from replacing the heavy chains with a retractable elastic band system or placing internal floats on the chains to prevent them from contacting the bottom. Tisbury officials have debated for years the benefits and drawbacks, including cost and holding strength, of “low impact moorings.” Installation is currently subject to the approval of the harbor master.

The relationship between seafloor disturbance and eelgrass habitat also underpins a three-year study by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) on the impact of fishing with conventional scallop drags. It’s a method common to the Vineyard, where a shellfisherman tows a net basket built around a rectangular metal frame, the bottom of which is made up of large chain rings to keep it riding along the contour of the seafloor. A bar at the mouth acts like a spatula to scrape scallops off the bottom and into the basket.

In the study, now in its final year, drags were towed a set number of times over a predetermined area of eelgrass in the waters off Fairhaven during the fall–winter scallop seasons. Researchers then compared the health of the spring and summer eelgrass growth in that area against a corresponding plot that was left untouched. This summer, they will monitor the area for the third and final time.

The good news, according to DMF environmental analyst John Logan, is that based on preliminary results there’s no detectable loss of eelgrass attributable to the use of scallop drags. When fished properly, drags tend to clip the eelgrass as they skim the bottom but do not for the most part uproot the rhizomes, which are the source of new growth. “There’s sort of cautious optimism in terms of the sustainability of the fishery with regards to the habitat,” he said.

Colarusso is familiar with the DMF study. Speaking about his experience on the Vineyard during scalloping season, he said there is definitely individual shoot loss, but the extent of that loss and its overall effect on the health of the meadow varies by a couple of factors. These include the care and the skill of the fisherman and sediment type.

For example, Tashmoo, where dragging is not allowed, has a soft, silty bottom in which plants would be very easily uprooted. “What the seafloor is like makes a huge difference whether the impact is going to be trivial or be very significant,” he said.

In 1998, Martha’s Vineyard Commission water resource planners experimented with transplanting eelgrass. They harvested plants from off Eel Pond in Edgartown, tied them to small bamboo pins, and inserted them in the bottom of Sengekontacket Pond in two twenty-foot square plots. It didn’t work.

As if disease, water quality, and disturbances to the seafloor aren’t enough challenges, green crabs can also threaten eelgrass. An invasive species that arrived from Europe in the 1800s, green crabs are numerous in Island ponds and bays and can uproot eelgrass rhizomes and clip off eelgrass shoots when searching for food, which includes the clams and bay scallops that rely on the grass. They pose a problem for established beds, but are probably more detrimental to new beds, which are still sparse and less likely to recover from such disruption.

According to the 2003 final report from the commission’s experiment, “the eelgrass plantings were immediately damaged by crabs and, despite the use of exclusion fencing, over 90 percent of the plantings were gone within one month.” The report further noted that “the process was very labor-intensive.”

In 2016, following a die off of eelgrass in Nashaquitsa Pond in Chilmark, shellfish constable Isaiah Scheffer began the challenging project of eelgrass restoration with funding from an Edey Foundation grant. All of the transplanted shoots died within two weeks, according to a report on the project. High summer water temperatures at the time of the transplants and sediment suspension (in part attributable to the loss of eelgrass) were thought to be the main cause.

More recently, Scheffer tried growing transplants in small peat pots set into sand on submerged rafts. The eelgrass survived all summer, but did not survive the winter. A corresponding effort to plant eelgrass seed has met with limited success. In a recent conversation, he spoke like a man who learns from failure and is not about to give up anytime soon.

He said timing transplant efforts to when the water is cooler may be more productive. “We’re learning as we go along,” he said.

Narrowing of the channel that connects Nashaquitsa Pond to Menemsha Pond restricts water flow and may affect water clarity and temperature. Bank erosion is also a contributing factor. Some areas of the small pond may eventually be too shallow to support eelgrass, though Scheffer said he has seen eelgrass survive in six to eight inches of water at low tide.

The focus of both the seeding and transplanting are those areas that have traditionally supported eelgrass, and he is hopeful Nashaquitsa has not “reached the point of no return.”

Noting that scallop production is best when eelgrass is present in Nashaquitsa, he added, “If we want more bay scallops, we’ve got to figure out what is going on with eelgrass. That’s what it comes down to.”

Scheffer and Colarusso aren’t alone in trying to give the plants a boost in an effort to foster a healthier and more sustainable shellfishery. In 2019 and 2020 the shellfish group began experimenting with various methods and techniques of growing eelgrass in outdoor and indoor nurseries. One method is replanting dislodged, floating shoots of eelgrass in sand-filled wooden rafts suspended in the water column. The idea is to then sink the rafts and allow them to decompose even as the plants take root. It’s unlikely that the shellfish group would be able to scale up to replant entire meadows, Green-Beach said. But small, hard-won victories are welcome.

“I’m hoping that we can successfully establish small patches that will persist and reproduce. With time, it could accumulate to significant improvements, if all goes well. Which it usually does not.”

In a report published by the shellfish group on December 31, 2020, Green-Beach described the recent experiments and challenges in trying to reverse the impacts of development. “It is a frustrating realization,” she wrote, “but many of our efforts are really hindered by the detrimental effects of excess nitrogen and eutrophication.”

She said the shellfish group will continue to work with the towns, the Tribe, and, per the report, “the many pond associations to develop and promote nitrogen mitigation tools for our community.” She is optimistic that “if people know something is wrong or something is amiss and they’re given ways to help, most people will support the efforts that are going to help us in the long run.”

Colarusso agrees that transplanting is challenging, labor-intensive, and has a poor track record. “There are so many factors, many beyond our ability to control,” he said. He was part of an effort in Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island where he and a team of divers spent the better part of twenty hours underwater over the course of a week harvesting and moving sixteen thousand shoots one at a time. “Three weeks after the transplanting, a large storm came up the coast and everything was lost,” he said.

“This illustrates why we need to do everything we can to conserve the healthy meadows we have, because restoring them is so difficult.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)