Editor's Note: Hugh Newell Jacobsen died on March 4, 2021 at the age of ninety-one, shortly after this article was published in the Spring Home & Garden issue.

In the late 1970s, Hugh Newell Jacobsen was a sought-after modernist architect among the Washington, D.C., social elite, designing primary houses in the metropolitan area and second homes in Florida, the Caribbean, and beyond. Among his well-connected clients was Rachel “Bunny” Mellon, wife of Paul Mellon, heir to the Pittsburgh banking fortune. She was a well-known socialite, philanthropist, and good friend to former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy. Jacobsen claimed to have worked on no fewer than nine homes belonging to the Mellons, whom he described as personal friends of his own family and so wealthy that they “made Jackie look poor.”

It was not surprising, therefore, when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis hired Jacobsen to design a house and guest house for the much-needed refuge she decided to build on the Vineyard in 1979, after the death of her second husband, Aristotle Onassis. She also asked Bunny Mellon, who was a talented landscape designer who had created the now famous Rose Garden at the White House during the Kennedy administration, to design a series of gardens on her 340-acre Aquinnah site.

The houses on Red Gate Farm, as the Kennedy Onassis property is known, began as a series of conversations between Jacobsen and Kennedy Onassis, with memorable meetings held on the beach during which they discussed where and how to situate the main house on the large property. On one visit they drew a full-scaled plan of the home with their feet in the sand, which allowed them to walk through the proposed rooms and feel the relative size of the spaces. While Jacobsen valued these experiences with Kennedy Onassis, their collaboration was not entirely comfortable for either of them. Not only did Kennedy Onassis have strong ideas about what she wanted in her home, Jacobsen also had to adhere to certain aesthetic restrictions imposed by the town, requirements from two forces that he felt reined him in and adversely impacted his design.

“She wanted it to look like Nantucket. Nantucket is filled with nineteenth-century architecture, so she wanted a modern house that looked like a nineteenth-century house,” he told The Georgetown Dish in 2019, not long after the news broke that Red Gate Farm had been put up for sale by Kennedy Onassis’s daughter, Caroline Kennedy. Meanwhile, the town wanted “everything to have shingles and be built like little saltboxes with one story in the front and two in the back. I followed these rules laid out by the board so we could get the building permit. They don’t like modern architecture up there and that’s what I am….So, I did, made a plan, and I did it about nine times before it passed that board.”

By the time the project was finally under construction, Jacobsen and Kennedy Onassis had parted ways. Afterward, Jacobsen distanced himself from the final design. “As you may know, I have an ego the size of all the outdoors,” Jacobsen told The Georgetown Dish, “therefore I am going to sell my architecture to my client by saying the only way you can build that house is to build it the way I designed it. So, that’s why the house looks the way it does. Because I said, ‘If you don’t like my design, then you will have to do it yourself.’”

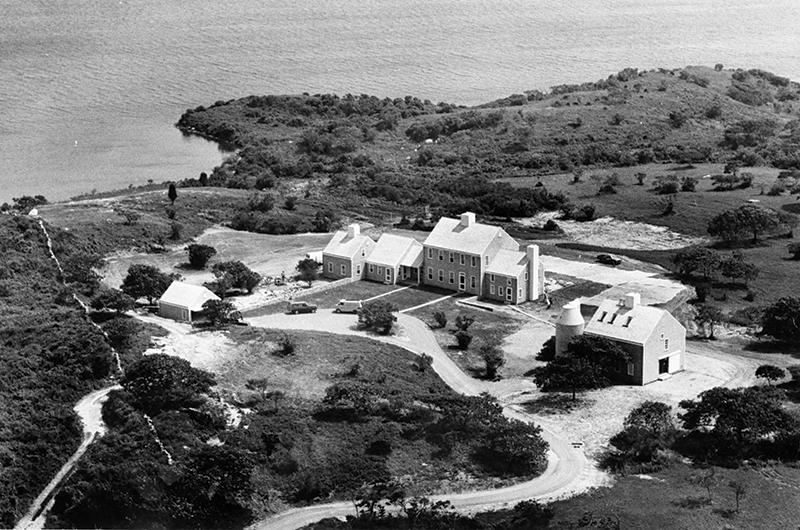

Nevertheless, the house that eventually emerged from their collaboration demonstrated a surprisingly easy hybrid of Jacobsen’s distinct modern aesthetics and Kennedy Onassis’s more traditional sensibilities, starting with its scale and discreet placement in its natural setting. The main house at Red Gate Farm was just over 3,000 square feet – a modest home compared with those owned by many of Kennedy Onassis’s societal peers. Jacobsen also designed a guest house as a simple two-bedroom, stripped-down Cape Cod cottage to which he added one distinguishable element, a tall silo-shaped tower. (The tower violated the town height restrictions and later had to be cropped by three feet.)

Jacobsen arranged the main house as a cluster of single-story saltboxes flanking a two-story colonial structure with a side-gabled pitched roof. He pierced the façades with traditional multi-paned windows, not typical in modern houses, but organized them in a decidedly asymmetric configuration, which enabled him to control natural light in the rooms inside and to direct views to the outdoors. A handful of large square picture windows framing extraordinary natural vistas substituted for Jacobsen’s preferred floor-to-ceiling modern glass walls. Stacking two stories was uncommon in modernist houses, but Kennedy Onassis wanted her bedroom to be on the second floor and the colonial prototype suited this configuration well.

The scale of the home suited Kennedy Onassis’s desire to spend the bulk of her Vineyard time outdoors in the property’s authentic natural setting, eschewing notions of undue formality. What’s more, her desire for complete privacy and isolation led Jacobsen to site her houses near the center of the property, invisible from the road and waterways, leaving the natural terrain intact. This was a relief to Islanders who had worried she might overdevelop the site, which then as now was one of the most unspoiled tracts of land on the Island: it has nearly one mile of Atlantic beachfront and encompasses the entire western shore of Squibnocket Pond.

Mellon did finish several gardens on the property, and for more than a decade after its completion in 1981, Kennedy Onassis and her adult children, Caroline and John, cherished the estate, as did Caroline Kennedy’s family after her mother died in 1994 and after her brother and sister in law’s tragic death in 1999. In 2000, Caroline Kennedy and her husband, Ed Schlossberg, replaced the house, which had not aged well, working with Deborah Berke, dean of the Yale School of Architecture.

The intensely private Kennedy Onassis apparently never spoke on the record about her opinion of the house itself. But when the Kennedy-Schlossbergs put the property up for sale in 2019, Caroline Kennedy wrote in an open letter to the Island that was published in the Vineyard Gazette that her mother “loved the old stone walls, the blue heron that lived in the pond behind the dunes, the hunting cabin that was the only thing on the property when she acquired it, the clay cliffs, the Wampanoag legends.…” Last year, in the most significant step forward for land conservation and public access on the Island in recent memory, the family sold most of those stone walls, dunes, beaches, and ponds to the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank and Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation – for far less than the original asking price.

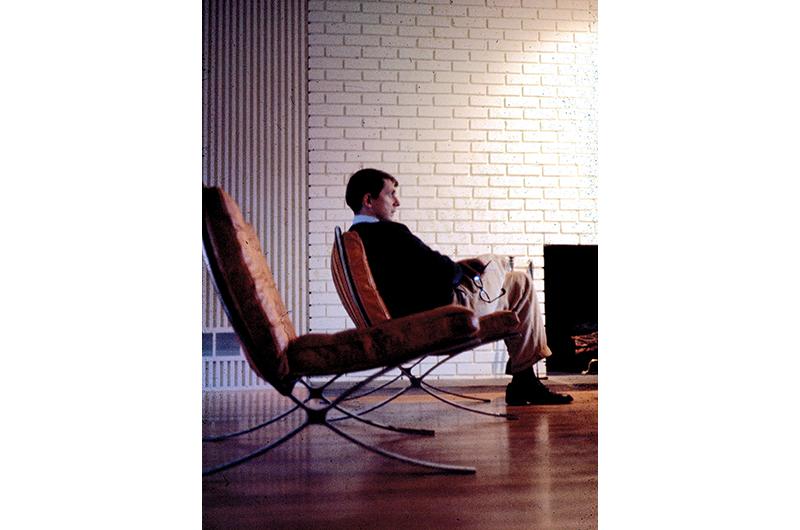

At some point during the design process for Red Gate Farm, Jacobsen brought Kennedy Onassis to another house on the Island that he had created nearly twenty years earlier. Though the visit did little to sway Kennedy Onassis’s design thinking at that time, Beech House, designed in 1963 for the Thoron family of West Tisbury, in many ways helped to launch Jacobsen’s illustrious Washington, D.C., and subsequent international career. Originally from Michigan, Jacobsen graduated in 1951 from the University of Maryland and went on to attend London’s Architectural Association School and Yale University, where he obtained a master’s in architecture in 1955 and studied under Louis Kahn. He then spent two years apprenticing under Philip Johnson in New Canaan, Connecticut, and a year in the modernist firm Keyes Lethbridge & Condon in Washington, D.C. In 1958 he hung out his own shingle in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., where his office remains to this day.

Emulating Johnson’s path, Jacobsen didn’t wait for a commission to get started, and built a small modern house in suburban Maryland that he completed in 1959. Designing a spec house as one of his first projects was a bold move, but one that enabled this unknown architect to showcase his style unfettered by the will of any client. The house was laid out on a bilaterally symmetric grid, minimal and clean, with an overt formality that was intended by modernists to elevate everyday living. The hillside site for the house allowed him to present the façade as a single story at street level, while the bulk of the two-story house descended down the hill, becoming ensconced by the surrounding forest, which he took advantage of by designing a long deck and walls of glass. This was intended to minimize any perceived barrier between inside and outside, another central goal of modernism.

If Jacobsen had a moment of uncertainty in his career, it may have been during the months the Maryland house sat on the market once completed. Eventually, however, it was purchased by a charismatic Naval Reserve officer, Christopher Thoron, and his wife, Janeth, who had returned that year after serving several tours in Europe, including three at the U.S. Embassy in Bonn, Germany.

Time in Europe had exposed the Thorons to some of the newest examples of modern architecture in the world, making them uniquely well suited to appreciate Jacobsen’s design.

“It was one of a kind, no modern houses in D.C. at the time, and it stood out like a gem,” Janeth recalled of finding the house. “Hugh thought we were the berries because we bought his house – we did not know it had been on the market for a while with no interest. Not a hot market for modern houses at the time. We loved it and were sorry to have to move.”

Acquiring one of the architect’s first houses marked the beginning of a long friendship between the Thorons and Jacobsen, one that extended beyond their time shared in D.C. After two years in their modern home, the Thorons moved to New York, where Christopher worked for the United Nations from 1960 to 1966 as a security council advisor. In 1962 the Thorons had their only child, daughter Elise, and asked Jacobsen to serve as her godfather. “Hugh was a magical and crazy godfather,” she remembered recently. “He had, really, a wry sense of humor and intelligence. I mean lots of fun, and my dad was the same.…I could see them being total peas in a pod.”

Christopher Thoron’s parents, Benjamin and Violet Thoron, had summered on the Vineyard since 1933, when Christopher was two. Benjamin, after working for an engineering firm in Boston, held several high-level positions in D.C. for the Public Works Administration before joining the Department of the Interior in 1941. He would later become business manager for the Washington National Cathedral from 1947 to 1951. He enjoyed the Vineyard, commuting to and fro around work, while Violet remained full time on the Island each summer with the children. She became an avid gardener like her close friend Polly Hill, namesake of the Island arboretum.

In 1946 they bought a nineteenth-century farmhouse they called High Hope, which sits on a beautiful wooded site with distant views of Cuttyhunk. There they raised Christopher and his siblings Ann and Samuel through the 1940s and 1950s. By early 1963, the clan had expanded to include several grandchildren and assorted spouses, and thanks in part to Christopher’s close friendship with Jacobsen, they hired him to design a home on a neighboring lot.

Beech House, which the Thorons named for a sprawling beech tree on the site, became Jacobsen’s first expression of his cluster-design buildings, which later became a staple in his design repertoire, especially for vacation homes where multiple adults would often be sharing the home while seeking privacy. He composed Beech House as a series of square pyramid volumes, each with a distinctive topknot and each intended to hold a different set of functions. In spite of inherent construction and cost inefficiencies, cluster buildings enjoyed some popularity in the 1960s because they offered internal separation and privacy while also allowing in more sunlight and air. Beech House was oriented on the site so that most rooms would have distant views of Vineyard Sound.

Jacobsen used the cluster concept, which directly emulated Louis Kahn’s breakthrough Trenton Bath House, to conjure up images of a New England fishing village. “Hugh was very inventive in his approach and in his work,” said his son, Simon Townsend Jacobsen, who is now a partner in the firm. “But he took examples from the very best before he came into his own. His greatest influences, particularly in the Thoron house(s) and the houses soon to follow, came directly from Philip Johnson and Louis Kahn. Then when you look at the detailing or the inside of the house, he switched from Kahn to Johnson and a little bit of Mies [van der Rohe]. He created for himself a kit of parts…not just using them but improving upon them.”

In addition to its distinctive pavilions, Beech House is defined on its exterior by an expansive four-foot-deep roof overhang that is held up by a surround of fifty-two slender cypress posts sunk into a perimeter bed of sea rocks used to capture runoff and protect the slab foundation. The overhang, requested by the client, protects the house from both summer sunlight and squalls. The house contains a sizable living space and four semiprivate bedrooms, but Jacobsen reduced the building’s perceived scale by placing it low on its wooded site and minimizing external details. The central hallway and entrance are a wall of glass, and every room has access to the outdoors via a pair of simple French doors glazed from floor to ceiling. The exterior cladding and interior trim is unfinished tidewater cypress, a material that holds up to the humid Vineyard climate, while the roof is a cement tile cast to look like cedar shake, a nod to vernacular building materials but updated in an effort to make a more enduring building.

The interiors demonstrated Jacobsen’s skill in manipulating natural and artificial light, particularly in the design of the dramatic skylight in the living room. Inside this space a coffered opening rising twenty feet above the floor and lined vertically with one-inch-square cypress guides the eye to a dramatic view of trees and sky. In the long hallway/gallery, recessed lighting washes the walls, making the interiors fully transparent from the outside in the evening hours, while softly illuminating art. Built-in furniture and functional details, such as a wall-spanning credenza and crate bookshelves, neatly conceal messy necessities, such as a firewood bin that could be conveniently loaded from the outside.

Jacobsen’s meticulous detailing and attention to craftsmanship was not lost on the younger Thorons. “We loved the house,” said Ann (Thoron) Hale’s son, Chris, who enjoyed Beech House with his cousins throughout the ’60s and ’70s. “It was a really cool place. It was all hand built in place by [contractor Donald] DeSorcy.” He remembered his Uncle Christopher, the architect’s friend, saying at one point, “I’ve looked all around this house.…It is FLAWLESS! There isn’t one mistake in the whole place!”

Beyond the family’s appreciation, Beech House won the highly coveted Architectural Record award of excellence in 1966, bringing Jacobsen critical recognition. That same year Christopher and Janeth Thoron hired him to design what would have been their dream summer home in Wainscott, New York. Their divorce in the next few years meant that house would never be built, but the two men remained friends and collaborators. In 1969 Christopher Thoron and his second wife, Luz Bustos, and their infant daughter, Amira, moved to Egypt, where Christopher had been named president of the American University in Cairo. Jacobsen soon became an architecture professor there, and was commissioned to design a new library for the institution.

“I had a memorable trip where Hugh was my escort to Cairo when I was about eight or nine,” Thoron’s older daughter, Elise, recalled. “We went through Rome, as you did on [Trans World Airlines] at that time to get to Egypt, and we had an amazing lunch with some engineering friend of his and another [colleague] from the American University…and these gentlemen left me sleeping on a bench in the Rome airport and went off to the bar.…I woke up and was like, ‘Where is everyone?’....I went to the Ambassador’s Club, where a woman there paged the gentlemen and she lit into them. And Hugh’s (unapologetic) response, ‘Well, there was an eighth of Scotch under the bench with our coats; of course we wouldn’t leave her!’”

Christopher Thoron died suddenly in 1974 at the age of forty-three, and the library was not completed until 1981. Nevertheless, it was one of the first large-scaled institutional commissions of Jacobsen’s career, one that showcased his ability to design monumental architecture. Inspired this time by the contemporary brutalist work of his former teacher Kahn, the building is composed of massive volumes of formed concrete, with floor-to-ceiling glass walls on an interior court that held a lush green garden and was protected from the Egyptian sun by a gridded concrete sunscreen that also shielded the interior rooms. As with Beech House, the library garnered international design acclaim that advanced Jacobsen’s career at home.

In 2012 the Thoron family sold Beech House to a longtime summer resident and his wife. By then it was showing its age, including mildew and dry rot, failings in the cork floors, and mid-century cabinet and mechanical systems that required attention. But the new owners were attracted to it for its architectural provenance. With the rise in popularity of mid-century modernism at the turn of the twenty-first century, it is not surprising that this house would attract an architecture connoisseur, especially on the Vineyard, where authentic mid-century homes are few and far between. Other than deferred maintenance, updating the hvac and plumbing, replacing the failed cork floor, and reconstructing a classic Jacobsen crated shelving wall, they managed to restore everything else to its original design.

They credit their success not just to Jacobsen’s detailed design, but also to the solid original construction by the renowned Island builder Donald DeSorcy.

“DeSorcy’s work was just exceptional,” said one of the new owners, who is a successful banking executive. “When I did the renovation, what I said to the guys who I hired was, ‘I’m not trying to change anything. I just want to fix the stuff that’s gotten damaged over the years.’ This is a 1964 construction where the most sophisticated piece of equipment was a twelve-foot level, (but) the house is just dead perfect.

“It’s a total time capsule,” he added. “In my view, Hugh did an incredible design.…[At the time I was buying the house], I had a brief telephone conversation with Hugh, and he was quite charming.…Hugh said, ‘I never worked so hard in my life and I loved that house’….He was charming and amazing.”

Nearly twenty years passed between the creation of Beech House for the Thorons and the designing of Red Gate Farm for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and nearly forty years have passed since. In the intervening years Jacobsen’s practice thrived, expanding both in scope and volume. Over time his son, Simon, also an architect, took on a greater role in the firm until he partnered with his father to form Jacobsen Architecture in 2007. Simon’s design approach built comfortably on his father’s brand, bringing in new building materials, up-to-date building processes, and even higher standards of craftsmanship to the endeavor. In 2012 a client who six years earlier had acquired the Jacobsen’s award-winning 1989 Patton House in Vero Beach, Florida, commissioned the firm to design a new home on the Vineyard.

The owner, a Washington, D.C., native and aficionado of Jacobsen’s oeuvre, loved the Patton House’s aesthetic, which was a much larger and exaggerated version of the clustered pavilion design Jacobsen first used on Beech House. (Post-Patton House, Jacobsen’s Florida houses clearly exhibited his design move toward postmodernism, the aesthetic movement that sought to fuse the abstract nature of modernism with classical and vernacular forms and details.) The client’s Vineyard house, known as the Aquinnah House, was completed in 2017 and captures the essence of Island vernacular as interpreted through Hugh Jacobsen’s pristine modern lens. It was the third and last house Jacobsen Architecture designed on the Vineyard.

“What Hugh did then,” his son said, “and what I do and the firm does together now, is abstract the vernacular – minimize it down.” The elder Jacobsen was by now well into his eighties, and although he did visit the site early to sketch out initial concepts, his son ultimately became its lead architect, collaborating seamlessly with his father as well as with project architect Richard Cho. Following Island precedent, the team chose a cluster composition to organize the Aquinnah House and garage buildings. In this case they clustered several gabled Cape Cod–style cottages, borrowing the most prolific historic form known on the Island.

Considering the trajectory of this design concept, it is somewhat ironic to recall how Jacobsen had balked at the idea of clustering New England saltboxes for Kennedy Onassis forty years earlier. Indeed, when Jacobsen walked the site early in the process with one of the clients, he shared his memories of the many months he spent on the Island designing Red Gate Farm, musing on how his ideas about modernism had clashed with Kennedy Onassis’s ideas about creating a traditional home.

For this latest house, the architects once again had to follow local building requirements restricting materials, form, and scale in an effort to preserve local aesthetics and the natural environment. The resulting buildings, built by Andrew A. Flake Inc. in Vineyard Haven, fit into a relatively modest building envelope with restrained elevations and are clad in cedar shake, the iconic Island material. The main house, which is 4,000 square feet, is a two-story building that reads as a single-story beach cottage on approach with a hidden side entrance on the top floor. The backside of the house, as seen from the privacy of the beach, is a glass-filled two-story façade that reveals the home’s rich interiors and how the rooms interact with the outdoors.

The house was designed as a slow reveal, understood only after approaching the building from a meandering road, walking along a long path toward an unseen coastline past three small shedlike units that house the garages and a utility room. The simple front door, painted a bright blue, belies the “wow” moment on entry that Jacobsen’s architecture promises. Directly inside the front door, a floating console bookshelf and glass bridge guides the visitor toward a precarious cantilevered glass staircase that leads down to the large central two-story living space. It’s the kind of architecture that demands a certain kind of careful procession through the space, requiring users to engage fully in the experience of the house.

But what animated the younger Jacobsen most in talking about the 2017 Aquinnah House when compared to past houses was how much better he felt the building was constructed, using state-of-the-art materials and methods that not only allowed them to sharpen the building’s appearance and improve on its design, but enhance its long-term durability.

“The [Aquinnah House] is put together so differently than a lot of our other work. It’s so tight and so trimmed. The thing is designed to defy the laws of physics when it comes to weather. It has to do with the building materials we use and the methods,” he said. The result is a house that sits easily and organically on its landscape, but promises for a very long time to stand as a testament to Hugh Newell Jacobsen’s near sixty-year relationship with the Island as well as to the firm’s ongoing exploration of the idea of modernism.

“Eloquence in the language of architecture is measured by how a building is put together,” said the younger Jacobsen. “We endeavor to design buildings that belong, make the site look better, and hopefully never shout.”