On a bone-chilling, gray morning last year, Jo Douglas drove her mud-splattered pickup down a dirt road that heavy rains had turned into a slough. She was headed for a three-acre parcel of woodland off the Edgartown–Vineyard Haven Road in Tisbury, rented from the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission, where she was keeping the piggery for her business, Fork to Pork.

The sight of her truck sparked a hubbub among the herd – they knew that cuisine from some of the finest eateries and markets on Martha’s Vineyard was being DoorDash-ed their way. Today, the offerings were from Alchemy, Deon’s Kitchen, Beach Road, The Port Hunter, Back Door Donuts, Vineyard Grocer, and Reliable Market. Also included on the menu was a crowd favorite – scrambled eggs and oatmeal from the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital cafeteria.

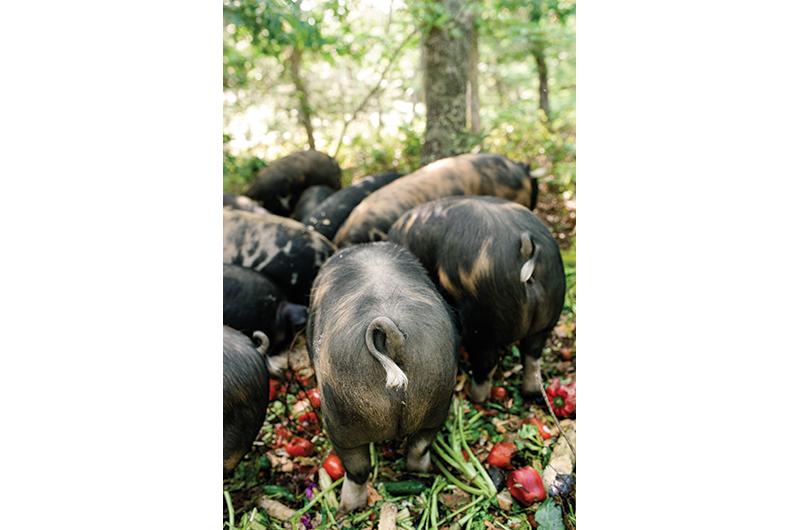

This is a twice-a-day ritual for Douglas, who is twenty-eight, from early spring through late autumn. Her pigs aren’t kept in pens. They roam the woods and forage for roots and bugs, which makes up about 30 percent of their diet. The rest is food scraps that would most likely have otherwise been shipped off-Island to a landfill.

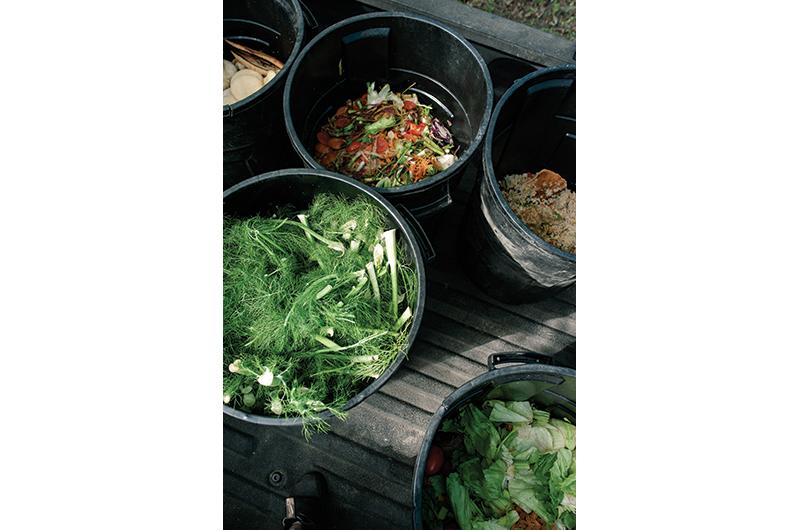

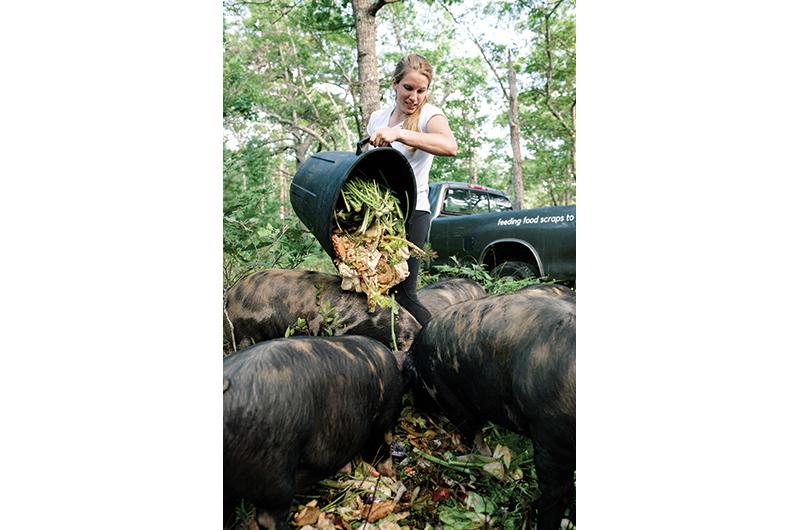

“Carrot tops are a big favorite, so are avocados, lettuce, beet greens, papaya, and tomatoes,” she said, hoisting a thirty-two-gallon trash bin over her shoulder with ease.

She carried the mélange into the woods, surrounded by an adoring crowd. Some pigs demanded to be petted and Douglas happily complied, greeting them all with maternal affection. Olive, an American guinea hog, appeared to talk back to her.

“I usually don’t name them, but Olive is special,” Douglas said, petting the 200-pound pig leaning into her.

The pigs and piglets were a diverse group: a mixture of Yorkshire, Hampshire, Tamworth, American guinea hog, Gloucestershire old spots, and Duroc. Normally, Douglas doesn’t raise piglets, but Olive was apparently pregnant when Douglas bought her. Most of the pigs came from three farms in Carver, Massachusetts, but Douglas found Olive on Craigslist, in a nearby town, and it turned out to be a mission of mercy.

“When I got there, she was shoulder-deep in muck,” she said. “The guy didn’t even know they were American guinea hogs, which is a very desirable breed. He really didn’t know what he was doing.”

Douglas dumped the barrel and a raucous party ensued – the woods echoed with loud snorting and grunting, and an occasional squeal of a piglet being put in its place. The biggest swine initially dominated the buffet, but eventually all got their turn.

Piglets ran off their ensuing food rush, darting among the trees with remarkable speed. Two of them scratched their hindquarters on the same sapling in a comical twerk. The adults, meanwhile, settled into their food coma on a fluffy mattress of wood shavings, courtesy of South Mountain Company. The piglets soon piled on.

Calm descended. The woods went quiet. Hog heaven.

“Most commercially raised pigs eat soy and corn feed and the only surface they know is cement,” Douglas said. “My animals have a good life.”

Douglas got the farming bug when she was a teenager going to farm school in Athol, Massachusetts. “I loved it right away. I knew it was what I wanted to do. I was hooked,” she said. After getting a degree in sustainable agriculture and food production at Green Mountain College in Vermont, she went on to work on numerous small-scale farms around New England. She was caretaking a farm in Connecticut when she began Fork to Pork LLC, but had to shut down unexpectedly when the owners cut short their planned year abroad.

Convinced she had proof of concept, however, in December 2018 she bought a one-way ferry ticket to the Vineyard, moved into her family’s seasonal home in Oak Bluffs, and started anew. “I had no idea if I’d find land, or get restaurants interested, or if they’d want my pork,” she said. “But I always knew I wanted to end up on the Vineyard. I spent my summers here growing up and I love it here. This feels like home.”

Since then she and her brood have bounced around a bit – a quarter-acre on Island Grown Initiative’s Thimble Farm at the Oak Bluffs–Vineyard Haven border, a short stint at Beetlebung Farm in Chilmark where there was rooting to be done, the three acres rented from the land bank. And this past spring she moved operations again, this time to Gretta Hill Farm in Oak Bluffs, owned by Mark McGlynn and Pat Ingalls.

“Last August, I was in the parking lot at NAPA and Mark saw my truck and said if I ever wanted more land to farm he’d be happy to help,” she said. “It’s a beautiful spot. I have an acre of woods and there’s also a barn, which came in handy in April when it was so cold. It also has a water source close by so I don’t have to haul water by hand, which is a huge help.”

Although her business plan went out the window in March thanks to the pandemic, Douglas was determined to keep Fork to Pork going in some capacity. “I made a lot of progress the first year. People really responded to the concept. I had to maintain a presence of some kind,” she said. To make up for the lack of food scraps in the early spring, she purchased grain with a grant from the American Farmland Trust Covid fund. Knowing she’d be getting fewer leftovers from restaurants, she also reduced the herd by over half for 2020.

“I also kept the number down because if I got Covid it would have been hard to find someone to manage thirty pigs,” she said.

As she spoke she turned on the hose and gently showered this year’s thirteen Idaho pasture pigs. The din of their delight was so loud it drowned out all conversation. An eighteen-inch high, solar-powered electric fence keeps the pigs from straying. “People always ask how this little fence can contain them, but it works really well,” she said. “They’re very content and they get to romp around and root all day, so they’re entertained. They have no desire to leave.”

When she entered the pen, they sidled up to her, tails wagging. “They like to have their belly rubbed, like dogs,” she said, petting and patting the brood surrounding her. “A lot of breeds are skittish around humans, but Idaho pasture pigs are known for being affectionate. I love these guys.”

Noticeably absent is the ambrosial bouquet of a typical pig farm. Only the musk of damp understory hangs in the air.

“They’re clean animals; they spread their manure out and they go away from where they eat and sleep,” Douglas said. “I’ve seen a day-old piglet detach from her mother to go pee. They’re incredibly smart. Pigs rank fourth in animal intelligence behind chimpanzees, dolphins, and elephants.

“They have a reputation for being dirty, but they roll in the mud because it cools them off. They also use it as sunscreen. They can get sunburned the same as us.”

Fork to Pork is built on a simple premise – feed pigs a healthy diet of food scraps that would otherwise be shipped to a landfill, and give them healthy lives in the open air. And while most commercially raised pigs in the United States receive ractopamine, a drug that promotes muscle instead of fat, which hasn’t been approved in the European Union, Russia, or even China, Fork to Pork pigs are completely drug free.

“I’ve been a big environmentalist my whole life,” she said. “Americans waste 40 percent of the food we produce. These pigs can eat waste that would have been shipped off-Island to a landfill and they provide top-quality meat. It’s a full-cycle connection. Composting is a step in the right direction. But feeding food waste to pigs is a full two places higher up on the EPA’s [Environmental Protection Agency’s] Food Recovery Hierarchy. Feeding food waste to livestock is right after feeding it to humans.”

Douglas estimates her pigs consume about 300 gallons of food scraps each day in the height of summer. She provides buckets to participating victualers and food markets, with a list of dos and don’ts (meat, bones, fish, and onions are off the menu). Pigs can eat between three and seven pounds of food in a day. Feeding thirteen of them requires a lot of bucketfuls. Put another way: when she gets her weaned pigs they average around forty pounds; when full grown they average 250 pounds.

When it’s harvest time, the pigs are taken to an abattoir in Westport, Massachusetts, that implements the methods of storied animal welfare activist Temple Grandin. All the pork comes back to the Island – mostly to the restaurants that supplied food scraps, and a few to caterers. The pigs come back whole. Some end up at pig roasts, including at Nomans and Coop de Ville, both in Oak Bluffs. Some also end up at The Larder in Tisbury, the only retail store that carries the Island-raised pork.

Being the sole Fork to Pork employee, in normal years Douglas puts in eight- to twelve-hour days, seven days a week. She does a lot of heavy lifting – collecting twice a day, making fifty stops, and covering sixty miles a day in peak season. To relax, she works out at CrossFit MV on her lunch break.

Athletics are a big part of her life. She’s the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School girls’ varsity lacrosse coach and assistant coach of the JV girls’ hockey team. She also teaches CrossFit classes and drives the Zamboni at the Martha’s Vineyard Ice Arena. “I’m the first woman to have the job,” she said, with a hint of pride.

Indeed, the one possible upside of the current situation is fewer mouths to feed has allowed her more flexibility. Instead of spending eight to twelve hours a day collecting food scraps, she spends three to four hours making the rounds. “It’s a little sad because I don’t get to spend time with the chefs, but it also gives me time to do other things,” she said. “I’m teaching twelve CrossFit classes a week. Last year I could only do three.”

In other words, Douglas exudes vitality. She talks about her mission with the zeal you’d expect from someone who relaxes by working out at lunch during her twelve-hour workday.

“Sometimes people see me on my rounds and say, ‘There’s the garbage lady.’ I love it,” she said. “One of the great things about this job is that I get to interact with people all day. I get to talk to them about what I’m doing. People really respond to the concept. It’s win-win-win.”

Initially, though, Fork to Pork wasn’t an easy sell.

“At first I was a little hesitant. I had farmers ask me for scraps before, but they didn’t stay with it,” chef Deon Thomas, owner of Deon’s Kitchen in Oak Bluffs, said. “Jo comes in here with a big smile and positive energy, how could I say no to this kid? My staff was sad when she stopped picking up in November.”

“It seemed like she had it really well thought out,” chef Frank Williams, of Beach Road in Tisbury, said. “We tried it with local farmers before, but it didn’t work out that well. Jo’s got it down. She’s reliable and organized and really passionate about what she’s doing.”

“I had just moved to the Vineyard from New York [City] when Jo proposed the idea,” chef Christopher Stam, of Alchemy in Edgartown, said. “It’s not something you think of in New York. My [general manager] was skeptical because it hadn’t worked out in the past, but she made a great first impression. You could tell she was on her game.

“The quality of the meat is fantastic,” Stam continued. “It’s clean, pure, flavorful pork. There’s really good fat layering, just enough to keep the pork moist.” Stam said his first dish with Fork to Pork pork was a grilled pork loin over polenta with escarole. “It flew off the shelf, people loved it,” he said. “People really respond to the story. They don’t expect to see ‘Tisbury raised pork’ on the menu.”

Beach Road’s Williams was equally enthusiastic. “I’d eat a lot of our scraps myself, so I know her pigs are eating good food,” he said. “I like doing the butchering; you can utilize every part of the animal. It’s great for me because I can make fifteen different dishes from one pig. My customers loved it.” In addition to chops, Williams made rillettes, pot au feu, prosciutto, and head cheese, to name a few.

“One day Jo came in to try several of the dishes,” he said. “The people at the bar didn’t know who she was, and she got to hear them rave about her product.”

Ironically, perhaps, Douglas was a strict vegetarian for eleven years and only began eating meat again in her senior year of college after taking an animal proteins class taught by a chef who was an avid hunter.

“From an environmental standpoint, it can be more ethical to eat locally sourced meat than tofu that was shipped from California,” she said. “When you eat meat that was humanely raised and don’t waste any of it, you honor the animal. I love them, but we do need to eat.”

Still, the cycle of life can be emotionally taxing. Four months after our first meeting, I asked Douglas about Olive. She took an uncharacteristically long pause.

“Olive is gone,” she said with a slight quaver. “That was definitely hard. I have a great photo of the two of us, it’s one of my all-time favorites. I framed it and gave it to my mom for Christmas.”