“What you mought call me? You mought call me captain.” -- Robert Louis Stevenson

Those of us who know him, know him as “the captain.” You go down to the Black Dog Tavern in Vineyard Haven and ask around, “Hey, you see the captain?” And everyone you ask knows who you mean.

We know him as “Cap,” as in a chance encounter, “Hey, Cap,” to which the reply might come, “Cookity!” which could easily be followed by a bear hug. Or we know him as “Bob,” when we stop by his farm and find him under one of his old vehicles and ask, “Hey, Bob, what’s the new snafu?” The reply would come back, expletives deleted here, regarding the poor quality of the engineering of the particular part of the vehicle he was trying to access.

Then there is the title used when running into one of his sons, a.k.a. “the boys,” and we ask, “Hey, where’s your pop?”

Finally, there is the term reserved for his wife, Charlene, when she admonishes him: “Robert!”

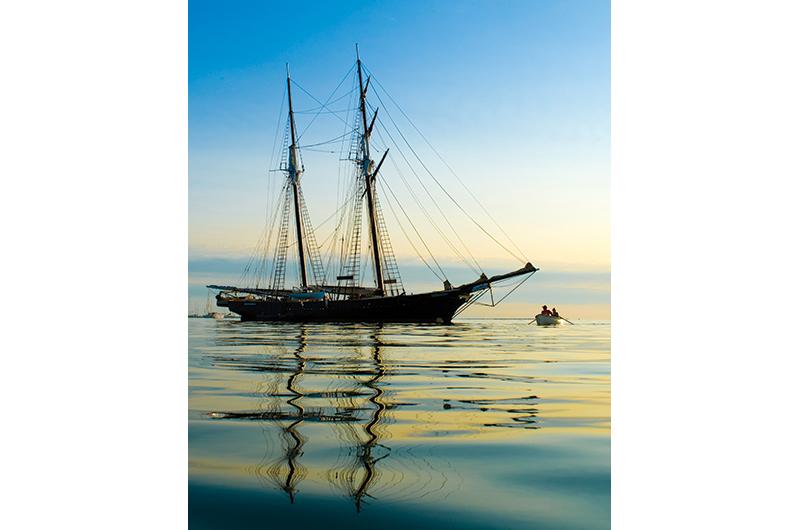

The first time I met Captain Robert Douglas was on the beach in front of the Coastwise Packet Company, next door to the Black Dog Tavern. I was there to meet the captain about the job of cook on the Black Dog Tall Ship Shenandoah. We got there at six in the morning to meet him, after a night of revelry at a campsite in the West Tisbury woods. I had never cooked on a tall ship before, hadn’t even seen the Shenandoah, and it wasn’t in the harbor yet. I had some experience on fishing boats, but most importantly I had some inside information: I knew his cook was jumping ship. I got the tip at the campfire the night before, as stories of the sea and boats were being passed around, among other things. After a summer of hitchhiking and playing music on the street, it sounded like the respite I was looking for. What I found was unexpected.

It was all sort of will-o’-the-wisp. “Hey, there’s a boat needs a cook.”

“Really? Cool, I’ll check it out.”

Maybe the fates were involved, because all of a sudden there I was, on the beach, and there’s the captain. I had no idea how much my life was about to change. As I approached him my first impression was, “This guy looks like an old Yankee type,” and I was glad. The last interview I’d had was with a fishing boat captain who barked at me when I met him, “Let me see your hands!” and grabbed said paws to feel for calluses, and who later, while we were out dragging, grabbed me by the throat and threatened to cut me up in pieces. Long story.

Captain Douglas didn’t come across as that kind of guy, and after we shook hands and looked each other in the eye, the interview proceeded: “So, can you cook?” and my reply, “I had better be able to, I got the job, don’t I?” Our eyes met again, he squinted a bit and then laughed. “Well, you have a point, let’s see how you do....”

Something transpired with those eye-to-eye glances. Something was awakened in me. I was rarely that cocky with an elder; it was like one of those times when you meet someone and you feel like you have known them forever, or in a past lifetime. After twenty-odd years of contemplation, and many miles at sea, it occurs to me that something else, something deeper, had occurred. He recognized the sailor in me. Maybe he saw something in my eyes, a similar glint that he had – or maybe he sensed my hangover.

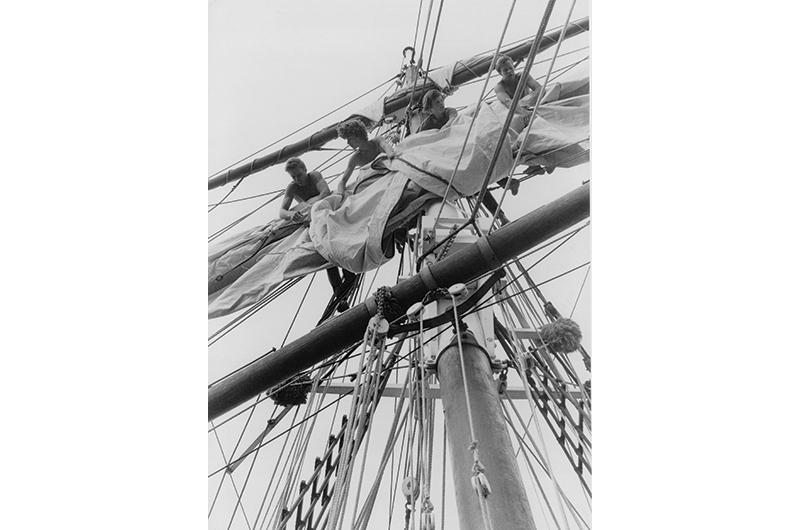

There are people who sail and then there are sailors. The former go out on boats, ships, what have you, for recreation now and again. The latter are different. They have the sea embedded in their DNA. Theirs is an odd mix of wanderlust and the need for a home, seemingly contradictory conditions that are simultaneously met when one has a berth on a tall ship. They board a vessel and they are home. They are happier on a ship than on land, and they can’t wait to get out into deep water and stay there as long as they can. Like so many callings, a sailor is something you are born to be, and all you need is a good midwife to get you started, or a good kick and a little serendipity. This is what happened to me when I met Captain Douglas. He pulled my “sailor’s soul” to the fore. I was far from the first. So many of the young men and women that have had the good fortune to crew or just sail aboard one of the Black Dog Tall Ships have gone on to careers on the water, or close enough to it to smell the salt air.

Life aboard ship is so different than life on shore, and that is perhaps one of the greatest lessons that Captain Douglas shared in his long tenure as master of the Shenandoah. Not only has he conjured the souls of sailors out to the light of day, but he has offered the world a lesson that becomes more and more valuable as time passes: relax!

That’s what sailors do best, after all. There is a title for particular jobs on board a ship: the cook, the carpenter, and the electrician are all referred to as “idlers,” primarily because they don’t stand watches, so when their work is done they are free to loaf. A good sailor is a good loafer. There are bursts of excitement followed by longer periods of just hanging around. On a long passage, even when there is wind, the course is set and if conditions are good nothing really happens...for days. Perhaps that’s why sailors are some of the best-read people you will have the chance to meet. I recall a friend of mine telling me of how he sailed from Long Island to Nantucket, or some such short trip, and he couldn’t stop talking about how boring it was. He, it turns out, was not a sailor.

After my first stint on the Shenandoah, in the fall of the year, I had thoroughly taken to idling about on the beach in Vineyard Haven. I eventually found a berth on a smallish boat for delivery to the Caribbean, ending up in Antigua, but a big part of me couldn’t wait to get back to the Shenandoah when she started her season in the spring. It was the magic of it all. The pure magic of sailing when conditions are good and the ship rips through the water – the power is immense. The captain at the wheel, the crew in the rig, and the cook in the galley cursing the captain for burying the rail, again.

When the sounds of the crockery flying around and smashing up in the galley subside, accompanied by commensurate oaths from the cook, the captain gives the mate the wheel and goes forward to the galley companionway: “How you doin’, cookity cook? Better clean that up...got any of the roast beef lying around?” Pure magic.

By building and sailing the Shenandoah, Captain Douglas has not simply recreated the past. He has made the past the present. He has not just offered people an experience that is slowly dwindling – that of sailing on tall ships – he has done something that comes from his own calling: he has preserved “the sailor.” In other words, the effect that “the Cap,” “Captain Bob,” the boys’ “Pop,” just plain “Bob,” or in some cases “Robert!” has had on the Island community, on myself, and so many other sailors can not be overstated.

Now after nearly five decades, talk of his selling the Shenandoah causes many of us to reminisce about all the incredible days aboard the queen of the harbor. Some of the most memorable times were spent in the main salon, in the dim glow of kerosene lamps, after the passengers retired to their racks. Then the crew sat around the massive gimbaled tables with the captain and often with his wife, Charlene, who on occasion would regale us with jokes only a sailor could tell. When the conversation would turn to the fate of the vessel, the captain would pause and ponder and then exclaim, “What I think I’ll do is just sail in one day, forget the hook, and just park her up on the beach next to the Black Dog!”

Those of us present at the gam, who know the captain’s tenacity and great spark of life, wouldn’t be at all surprised if that actually was to occur. If it does come to pass, however, I wouldn’t be surprised if on that day there would be a sound heard far and wide: “ROBERT!”

10 comments

10 comments

Comments (10)