If you’ve been to the West Tisbury Farmers’ Market in the last forty-five years, you’ve seen Robert “Bob” Daniels. You know the stand: a makeshift table of boards and milk crates curved under a shady tree near State Road, an elderly gentleman and his daughter presiding over cans of flowers and various vegetables. And, most of all, potatoes – large crates of all shapes and sizes, still dusty from the earth. Next time you’re there wish him a happy birthday – he’s about to turn ninety-five.

Of course, that’s not the only reason Daniels is kind of the dean of the place. Or even the main reason. Along with his wife, Lois Tilton Daniels, and other Island farmers, Daniels helped revive the farmers’ market in 1974. What’s more, he and his family pretty much invented the iconic bunch of flowers in a tin can business. “We were the first to grow and sell cosmos, and actually the first to sell zinnias at the market too,” his daughter Lynne says. “For years we had a black-eyed Susan that was seven-inches across. Everyone thought it was a sunflower, but it wasn’t. A friend in the Berkshires saved the seed for us every year.”

For his part, Daniels has always favored gladiolus. “People say, ‘Oh, glads are for funerals,’ but I like them,” he says. “I had one guy come every summer and buy a dozen every week.”

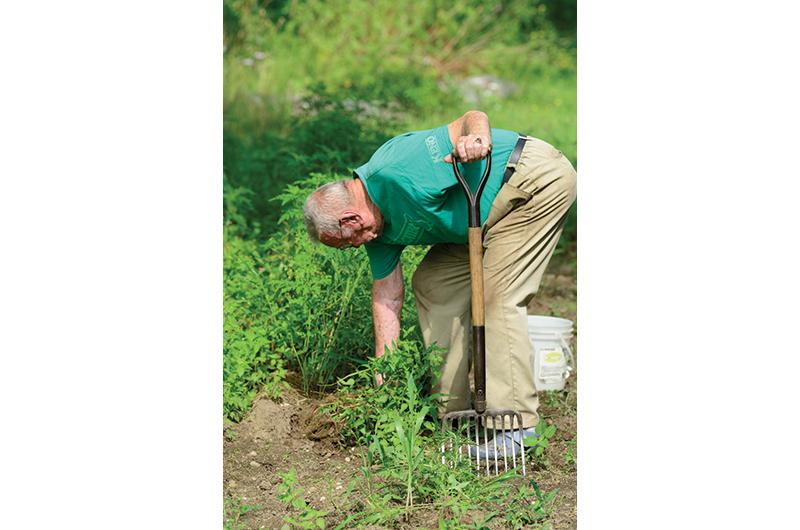

And yet it’s really the potatoes he’s known best for. Why potatoes? “I always liked to dig potatoes. I’d stop at my father’s. He always had a garden. I’d go out and dig potatoes and he’d come out and say, ‘I wish you’d quit, because I’d like to dig some!’

“We used to put in about 1,200 pounds. Now, not that many. And you can’t get all the potatoes now,” he says. At one point he estimates they grew about twenty different varieties. “But you can’t get the seed today. And if you can get it, it’s so darn expensive. You can’t afford to pay $27 for a pound of seed.”

People at the market aren’t buying as many potatoes, either. “A lot of our old customers have passed on too,” he says matter-of-factly.

As for digging, he’s never used a harvesting machine. It’s always been hand digging – something Daniels can’t do a lot of these days. His nephew helps; his son, Mark, does some.

Robert Sherman Daniels weighed twelve and a half pounds when he was born at home in Cheshire, Massachusetts, in 1924.

“I had a good start on most kids; I was bigger. But it took me a long time to figure out that not everyone was as strong as I was. I thought everyone should be able to do what I did,” he remembers. “That was one reason why no one ever gave me any trouble; they saw the things I did.”

Starting as a teenager he worked for his grandfather, a contractor in the Berkshires, for a dollar a day, mixing up cement in buckets and hauling it up to dump in the forms created for barn floors. In 1943, when he was eighteen, he was the youngest from his town to be drafted. He went into the Army Air Forces medical services, where he was trained to do dental repairs. He built full uppers and lowers.

After the war he went back to the Berkshires to work for a builder who specialized in the kind of outsized barns that weren’t uncommon in the agricultural area. One day he was offered his own gig, the opportunity to build a 50-by-200-foot barn.

“My boss says to me, ‘I’ll kick your ass if you don’t go take that job. What you know, you shouldn’t be working for me,’” he remembers. “You know, it’s not like that today. Nobody would do that.”

He took that job, and went home to tell his wife of two weeks that he had quit one job but taken another. It wouldn’t be the last time he surprised Lois over the next fifty-plus years of marriage. One day in 1969 he came home and told Lois, who grew up in Menemsha, that he had bought a farm on Martha’s Vineyard.

Despite her teaching career in the Berkshires, Lois had always hoped they’d have their own place on the Island. They’d spent summers on the Vineyard with their three kids, Lynne, Mark, and Becky, at a camp on Indian Hill in West Tisbury, and the idea of owning a little piece of land, maybe doing a little farming, appealed to them. Growing food was not anathema to the couple. After all, everybody had tended a garden in wartime and most of their neighbors and relatives kept them going in the ensuing years.

The only problem was that Daniels hadn’t bought the particular farm that Lois had her eye on, and she wasn’t too happy about it. “She didn’t talk to me for five weeks,” he remembers.

He paid $12,000 for the twenty-two-acre parcel in Edgartown that would become Old Town Gardens. He could have gone for a much bigger parcel for only $8,500. But this one had a shack he figured he could live in while getting the place in shape. He also didn’t have enough cash for the standard down payment. But times were different; a friend was the son of a local banker, and somehow the bank signed on for the full loan.

Daniels moved down to the Island full-time, took building jobs, and set to work on the farm, erecting a home and preparing the land while Lois and the kids spent the winters in the Berkshires until Lois retired in 1980. The property had previously belonged to Walter Averill, who grew a few flowers here and there, but also used his land to house his collection of junk cars and other treasures from the dump. It was quite a clean-up job, therefore, but soon raspberries, wineberries, blueberries, strawberries, and perennial flowers were flourishing, followed by fields of potatoes, squash, beets, onions, carrots, and annual flowers.

And at the starting bell of the farmers’ market every summer, Lois was there, adding her jams, jellies, breads, cakes, cookies, and pickles to the mix of fruits, vegetables, and flowers they harvested every week. “My mother was a hell of a baker,” says Lynne, who even as a girl enjoyed helping her mother at the market. “The best oatmeal bread you’ll ever have my mother made.”

Lois died in 2005 while suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. She was a lifelong lover of books, and her collection, along with her Beethoven records, still line the walls of the “catch-all” light-filled workspace Daniels built that’s attached to the kitchen of their house at the farm.

All around the room are rustic but orderly shelves lined with mason jars full of saved seeds, tins of nails and screws, baskets, buckets, boxes, tools, and all the various time capsules that collect during a half-century of farming and living in one place. Attached to that room is another greenhouselike space, where these days Daniels perches atop a stool to sort potatoes or onion sets or flower bulbs. It’s not hard to imagine how he added on to the core of the house as he found materials he could recycle from jobs or picked up some extra timbers from builder friends in the Berkshires. He is proud of how he pieced it all together.

But while the outer rooms are purely functional, you can tell from the handmade cherry cabinets that Daniels wanted Lois to have a warm and homey kitchen in which she would enjoy spending time. In conversations about her he hits one note again and again: “She was so smart. I never realized just how smart she was. I don’t think you do until they’re gone.”

These days Lynne is making jams and jellies like her mother did. She also harvests and arranges flowers, picks fruit and vegetables, and accompanies her father to the market every Wednesday and Saturday in summer, and to the Saturday market at the Agricultural Hall in winter as well.

“I like it,” she says of the farm work. But whether or not the farm will stay in the family is difficult to say at this point. It’s hard enough just to keep the farm afloat; leasing land to Donaroma’s for greenhouses, in addition to the market income, has made it possible to keep the farm going and Daniels in the home he’s lived in for fifty years. But with the exponential rise in property values, the reality of real estate taxes makes selling the farm almost inevitable.

Not surprisingly, Daniels is not at all happy about this. “But what are you going to do?” he says. “These days it’s all about money, money, money,” he laments. “The way it was, it was neighbor help neighbor. Now it’s neighbor screw neighbor.”

The good news for the dwindling population of potato lovers is that for the short term, at least, he has no intention of stopping what he’s doing.

“It keeps me out of trouble,” he says. “It’s something to do and it keeps you active. Too many people think retirement means you sit on your ass and do nothing. And they’re not here for very long afterwards.

“I had a friend who worked for GE for fifty-five years. He came home after retiring, sat on the porch in a rocking chair, and in six months he was gone.”

Daniels has no plans to sit down then, or, for that matter, to quit expressing his opinions. But see for yourself. Stop by his stand at the market and say hello. And be sure to wish him a happy birthday.

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)