The minute Rick Bausman parks his white Ford van at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, he’s surrounded by eager students. Bausman, fifty-six, bounds out of the driver’s seat. His athletic build appears to corroborate tales of rock climbing and spearfishing. His outfit, a T-shirt and flip-flops on a chilly – actually, straight-up cold – day, speaks subtly to his independent streak. He slips his keys into a pocket in his hiking vest and hitches up his well-loved jeans.

“M, how are ya doing? Great kicks, I like the blue! Grab a drum!” he says, making connections with each student. Bausman has been working with many of these teenagers, all of whom are on the autism spectrum, since kindergarten. R wears earphones to mute intense sounds. O is accompanied by a full-time assistant. J directs his gaze fiercely at the ground. (For privacy reasons, the school asked that their full names not be published, so they will be referred to by first initials.) Bausman, who is married to third grade teacher Jennifer Bausman, with whom he has raised four now grown children in a “blended family,” appears to form a natural connection with all his students. One boy lays his head on Bausman’s shoulder.

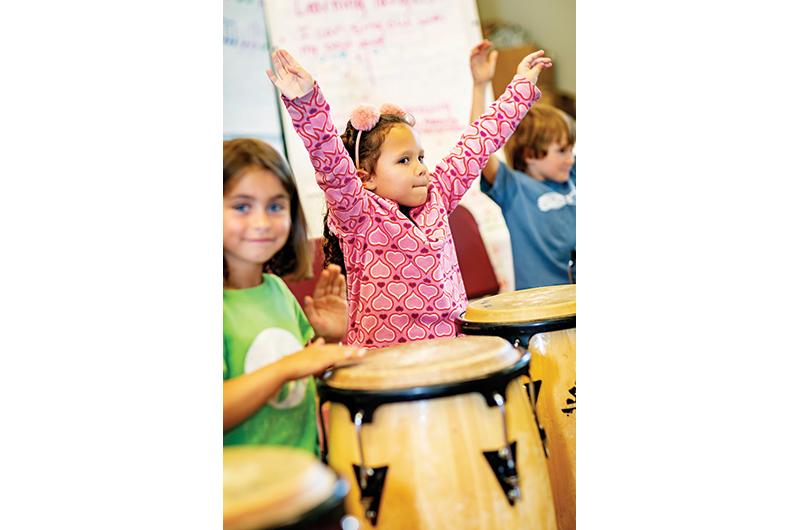

Though his curriculum meets the state mandated framework for working with students on the autism spectrum, no one’s thinking about checking boxes today. As with all of his classes, there is more going on than just a groovy beat: the group is about to experience songs, stories, and cultures contained within rhythms. Bausman takes his seat and the class forms a circle, a drum in front of each student. It’s time for the now

familiar rhythms from Nigeria, Cuba, and Haiti. And for humor.

“Ooh, there’s goo, it’s stuck to my shoe,” Bausman sings in a low voice, softened with flat New England vowels. His eyes crinkle mischievously and he drinks in the students’ laughter. “Da, da-da, da, da-da-da, da,” he taps with a calloused thumb and stick on his three-foot-tall, well-worn conga and then circulates among the group, meeting students face to face, encouraging them to drum along.

Several more take up the beat. R, the boy with the earphones, holds back. Bausman enlists help from W: “Would you be my assistant?” She nods and together they coax R into moving his hands across the smooth skin of the drum.

Sometimes Bausman pushes the group after a song, asking, “How was that? Have we ever done it better? Remember, we watch ourselves and see our hands come down.” The next round is tighter. Forty-five minutes later class ends with a slow fading of the drum, down to a mere rub. It’s clear many have experienced stress relief, felt a confidence boost, and had some much needed fun.

“There’s so much I want to teach people through drumming,” he said afterward. There’s the value of community, of listening to each other, of self-regulation, of embracing diversity, of working through challenges and taking risks. And, perhaps most of all, the value of self-knowledge. “People don’t always remember they are important. Who you are is important to your community.”

This love for music made him something of an anomaly as few people in his family or community were musically inclined. “I remember the first time I played “Sweet Home Alabama.” I was like, ‘Whoa, this is it!’ I got to come in after the famous first few notes, which felt like an airplane taking off. Very exciting!”

Bausman’s father was a Baptist minister and the family moved often, which may help explain not only the zeal with which he shares his love of music, but also his ease with new people from all walks of life. “I liked seeing new places. It was sad to leave friends, but I had the sense I was always going to make new friends,” he explained.

Drawing on his experiences as a church youth group assistant, lifeguard, and swimming instructor, Bausman first came to the Vineyard in 1980 as a seventeen-year-old counselor for Camp Jabberwocky, a camp for people with disabilities. Madeline Way, who is now the director of Project Headway Preschool at the West Tisbury School, was a fellow counselor and remembers meeting him at the ferry. “I picked up a curly, long-haired boy who had come straight from Mexico,” she said. “Rick was immediately a really, really, really great counselor. He became part of the camp community and understood it right away.”

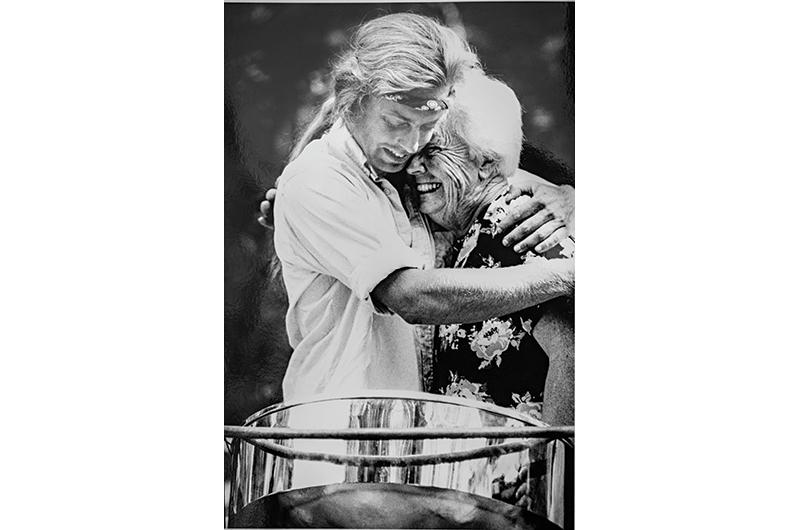

From the very beginning, she said, Bausman had a way of making performing accessible to almost anyone. She recalled in particular a Jabberwocky performance of Music Through the Ages, which involved a camper with a visual impairment, R.G., who also couldn’t stand and slumped when sitting. Bausman and the camp director fashioned a stand for the camper, who happened to love Elvis, so he could be comfortable on stage. “During the play, when it was Elvis’s turn to be on stage…all of a sudden R.G. was in the stand in a sparkly white Elvis costume with his head up high clapping and singing. It was amazing.”

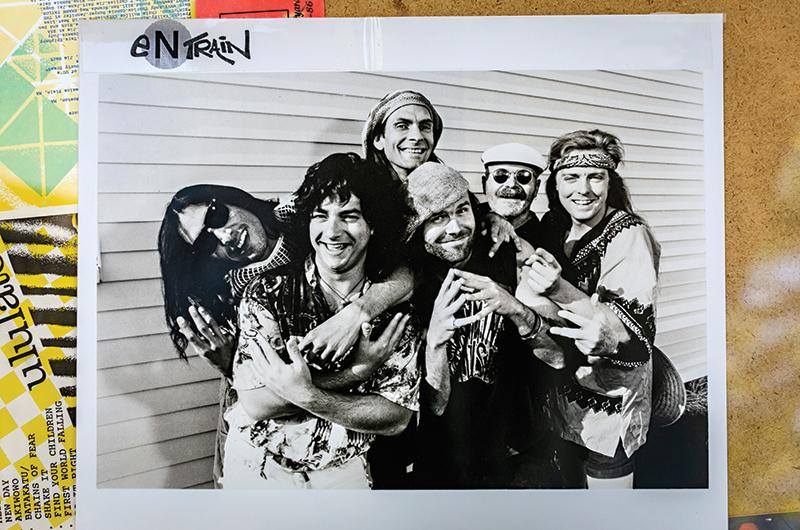

For the next twelve seasons Bausman worked as a Jabberwocky counselor, devoting himself to helping those with disabilities and pursuing his dream of rock and roll fame. The Island music scene was relatively vibrant at the time, and at the old Wintertide Coffeehouse at Five Corners in Vineyard Haven he connected with a group of drummers known as Die Kunst Der Drum (German for “The Art of Drum”). Today many of its members are still a part of a popular beach drumming cohort that Bausman organizes; in the warmer months they perform Tuesday nights at Joseph A. Sylvia State Beach in Oak Bluffs. He also played regularly with the popular drumming-focused band Entrain and with the Ululators, both of which he helped found.

Though Bausman enjoyed performing as much as teaching, when Entrain invited him to join their national tour he realized he had a major decision to make: either pursue his dream of becoming a rock star or devote himself to helping others as a drumming instructor. “It was a lot like jumping into a pool without knowing how much water was in there,” he remembered. “How hard could I hit the bottom? I was young, twenty-five, living in a tent for most of the year, crashing on a couch for the coldest months….Still, it was time to put my ego aside and prioritize being of service.”

He took a job as a full-time employee of the state of Massachusetts where he was responsible for setting up infrastructure for adults with disabilities. “It was a great time for me to be here and help get some things started for this population through MV Community Services,” he said. But he never lost his desire to use music as a vector to teach, and in 1986 he gave up the job and founded The Drum Workshop (now Rhythm of Life), a nonprofit that supports his workshops and outreach. He hasn’t looked back.

“Don’t joke around with me,” Bausman likes to warn others. “I say yes.”

One big “yes” he gave was to a preschool teacher who invited him into her classroom back in 1986. This expanded into the implementation of his drumming curriculum at every Island school. “He understands the nature of schools so well and is full of possibilities,” said recently retired Edgartown School principal John Stevens. “During last year’s MCAS, we asked him to do a quiet activity. He worked with his classes on re-skinning a drum from Haiti, which I find significant. It’s bringing back to life an instrument.”

In addition to teaching in all of the Island schools, Bausman often teaches at Windemere Nursing & Rehabilitation Center and at the various Island councils on aging. Elsewhere he’s hosted all night drum-a-thons with teenagers. He has worked with gang members in Boston, with Palestinian youths, and with wheelchair-bound adults in Providence, as well as in various jails and orphanages around the globe. “I sense where the bar should be and what style of drumming is called for,” he said when asked how he navigates among so many varied groups. “It’s challenging, but it wouldn’t be much fun if you aren’t challenged. Kind of like mountain climbing.”

A curriculum he developed for Parkinson’s patients is today used in other locations, including an agency in Springfield, Missouri. It’s a hands-on program, he said, that offers a form of therapy that isn’t boring or painful and has profound anecdotal results; many drummers report having better mind-body awareness, walking and feeling abilities, even better coordination of hands. “They want to make good music and over time their physio-neuro pathways are improved.”

In the winter of 2017, Bausman put on a concert in Zambia after designing a program for village children there with special needs. He recruited drummers from nearby Makuni village and played with them every day, asking them to continue the program after he left. They taught him southeastern African styles and he taught them the Haitian styles that he learned from master drummer and instructor John Amira twenty-five years ago. In 110-degree heat, under a huge tree, they put on a concert for the community complete with dancers.

“What an honor,” recalled Bausman.

Then, in a Zen-like way: “Everything’s bursting right now. I may row a certain direction, but I also know when it’s time to change course….And I try to stay focused on one thing at a time.”

What Bausman is currently focused on is his newest project, which he calls Repercussions, and which has its roots in Kai Kok, Haiti, an off-the-grid village that he was introduced to by Islanders Pam and Nat Benjamin. The Benjamins have been periodically sailing supplies to the small village in their fifty-foot wooden schooner Charlotte. In January of 2018, Bausman went along and taught at Kai Kok’s community center and also played with a renowned Haitian drummer, Aristille “Doudou” Sonnelle.

“[There] I discovered I really do know what’s what. Which surprised me a little bit. I hadn’t had that kind of context for what I’m doing,” said Bausman.

“The kids love him,” said Pam Benjamin. “During our last visit [to Kai Kok] one night, some kids were playing instruments we donated and others were dancing with Rick. Eight kids were holding on to some part of him. It was amazing!” She noted that some people from Kai Kok are now earning an income by performing at hotels using the musical skills that Bausman helped them develop. Earlier this summer Bausman returned to Haiti at the invitation of Sonnelle and others, including the minister of vodou for southern Haiti, on a twenty-five-stop teaching and drumming tour.

“One of the most powerful things I do is just show up. I let people know the world hasn’t forgotten about them,” said Bausman. The Haitians are especially generous with sharing their culture, he said, and were surprised he knew as much as he did musically. After playing a familiar Haitian rhythm for the village called Yanvalou, and in particular the break called kasé, they said, “Whoa, how do you know that?”

“I’d changed the rhythm. It made them laugh. It made them extremely happy that someone showed up and had taken the time to learn about them and their culture. It’s a real partnership. They offer me so much. I don’t know who is getting more out of it.

“Drumming is a living entity,” Bausman said. Since it changes over generations and because their culture has been oppressed, Haitian drummers appear to have lost some of the intricacies Bausman knows to be part of the sacred rhythms. “I’m an outsider,” he said of bringing some of the old Haitian techniques he learned decades ago back to their home island. “I’m teaching them stuff that belongs to them. It’s a process of sharing, which comes full circle.”

Circles, one senses, like the surface of drums, mean a lot to Bausman, who sees this endeavor also as enriching the Vineyard. “I can bring knowledge, joy, and spirit back to the Island. It fits really well with the whole idea of ‘tracing infinity,’” he said while tracing an infinity symbol with his finger over and over on a table. Tracing Infinity is also the name of his band, which recently released an album called Shadows of My Innocence.

“Everything in my life has led me to and prepared me for this moment and I didn’t exactly see it coming,” he said, beaming.

Although Bausman has never been arrested, he has been told not to bring his drum to Menemsha again. One night in the early 1990s, Bausman and his friends from Die Kunst Der Drum put on a free concert at the popular sunset beach. The chief of police for Chilmark missed the show because he spent the night writing 850 parking tickets.

The next morning, the chief called Bausman to ask him to leave his drum at home next time he came up-Island. Die Kunst then began rotating beaches and keeping the location a secret; in those days, Camp Jabberwocky headquarters sometimes received 100 calls a day to ask where they were going to play that night.

Bausman’s sunset drumming scene continues, though it has changed over the decades. Instead of carrying a case of beer, the crowd now is more likely to be carrying their kids. “It’s not the frenetic energy it was at one point, and that’s fine,” said Bausman. Now anchored at state beach, the sessions remain open to all music lovers, but are hosted in honor of Camp Jabberwocky. “It’s a scene. People are dancing in the waves!”

Still, it remains a performance, as opposed to a participatory, drum circle, said Bausman. It’s a place where this advanced group of drummers feels, “It’s our time to have some fun….In most of these ensembles someone is soloing around the rhythm.”

All grown up with adult children of his own now, Bausman is long past the days of living in a tent and beach drumming until the wee hours of the morning, but not entirely past the point of wondering how close the bottom is to falling out. During the summer, he offsets his mortgage by playing gigs with the Beetlebung Steel Band, Miracle Cure dance band, Ululators, and Entrain.

“I love what I do,” he said, “but it doesn’t afford me any savings or retirement. I have accepted I have to fundraise. And that’s a lot of hard work.” While Bausman is the “heart, soul, and dishwasher of his operation,” his board helps by writing grants. Rhythm of Life does not hold a formal fundraiser, but donations trickle in; some donors have been committed for decades.

Bausman credits the Vineyard for being a super supportive, open-minded place. “Some other parts of the country are skeptical whether the elderly, young children, people with disabilities can do this….There’s a curiosity here and

variety of people who continue to help me. I always find new populations and ideas here.”

Having been invited to share those ideas all over the world, he explains that it’s all a product of the Vineyard. “Our Island has no raw materials or produce we export. We export a certain kind of vibe, and I do this through drumming.

It developed here and grew here and everyone should take some credit here.”

He pauses, thinking about the people he has worked with over the years. “Most people don’t get to be in a band. I want to help [drum workshop participants] experience that feeling I had when I started to play.”