Bill Roman stood in his temporary office, gazing across the waterfront to a renovated Edgartown Yacht Club, whose walls and roof seemed to glisten with new shingles, even on this overcast spring day. Jutting 190 feet into the harbor, the venerable club had the look of vessel that had been spruced up and refitted for its next voyage – which, in effect, it had.

But something else was in Roman’s line of sight, something that served as a graphic reminder of the need for the $7.5 million project, which he has supervised as the club’s general manager. It was just past high tide and the harbor’s surging waters had lapped over portions of the waterfront and into the parking lot alongside the club, pooling three or four inches deep in places.

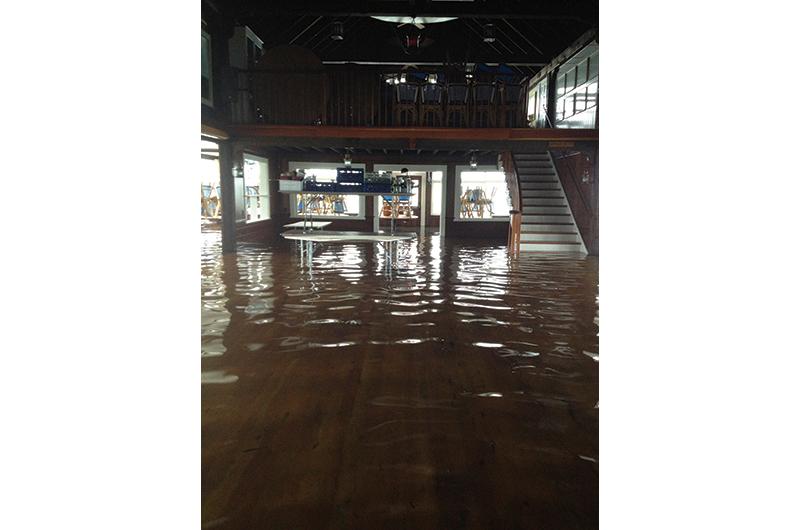

He’s not exactly Noah nervously trying to finish the ark, but over the years Roman has nonetheless had to develop a keen interest in tide charts, storm forecasts, and sea levels. It so happens that he celebrates his thirtieth year as the club’s general manager this year, and rare is a season when harbor water hasn’t flooded the clubhouse. Not to mention the two hurricanes in 1991 (Bob and Grace) and another in 1998 that merited small plaques on the wall noting high water marks.

“We might get a foot of water a couple times a year,” he said. “A few inches of water? Not unusual for it to happen four, five times a year. Some years you get absolutely nothing, then the following year, twelve to fifteen times you get flooded.”

That hopefully won’t be the case this year. The renovation project, completed by the yacht club’s traditional Memorial Day commissioning, also lifted the deck of the clubhouse, its kitchen, and other facilities two feet higher above the harbor.

It’s a scenario that is playing out in various ways and places elsewhere on the Island as encroaching water has forced residents, businesses, and municipalities to scramble, usually confronting the same calculation: float it, raise it, or move it. At the Island’s margins – from the Gay Head Light at the western end to the Schifter family’s 8,300-square-foot house on Chappaquiddick’s southeastern corner – expensive projects have dragged large structures away from eroding coastlines in recent years. But now it seems the number of projects (or planned projects) has proliferated, perhaps as scientific projections of coastal flooding become graver, not rosier.

Just down the harbor from the yacht club, the iconic, privately owned Vose boathouse had its deck raised another foot above the water. In the other direction, the town’s historic memorial wharf, alongside the Chappy Ferry landing, is targeted for a project that will reinforce its base and lift the structure by eighteen inches. Ultimately, the town may raise the entire parking lot alongside it.

At the Five Corners intersection in Vineyard Haven, perhaps the busiest and most prone to flooding on the Island, the Black Dog Bakery was closed during the winter for renovations that included raising its floor a foot. There’s talk of raising the town dock at Owen Park a foot or two as well. Meanwhile, up Beach Road, the developers of the old Hinckley’s lumber yard discussed building their project eight feet above the road with parking underneath. In fact, all of Beach Road is up for debate; the town and state are haggling about redoing the road and raising it to protect against flooding. It’s an ironic image of the future: the more than $41 million Lagoon Pond drawbridge, which was built several feet higher than the old one, is surrounded by road on either side that potentially will be under water.

Similarly, the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital sits on high ground, but its access roads will be seriously jeopardized by rising sea levels. (In other words, rest easy in the hospital – if you can get there.)

All along the waterfront in Oak Bluffs, sea level rise has impacted homes, businesses, and infrastructure. A portion of East Chop Drive already has been closed because of erosion, while the North Bluff, near the Lookout Tavern, got a new, higher seawall (with a popular pedestrian walkway on top). The permitting process is underway to enlarge and put a water gate in the Farm Pond culvert, mostly to improve water quality, but also to provide an outlet for storms and rising seas. The town is pushing the state for help on vulnerable roads, especially Seaview Avenue by Farm Pond and Beach Road by the hospital.

Up-Island, Menemsha Harbor has attracted attention, especially since the town’s only gas station is alongside the harbor in a vulnerable spot. “Seems like the water is over the dock more this year than most,” said selectman Bill Rossi at a meeting this spring as selectmen sought help through state grants. “It used to be people would take pictures of it,” added chairman Jim Malkin. “Now they don’t bother anymore.”

Growing accustomed to seeing water over wharves and in the parking lots is one thing. Processing the level of coastal transformation and the dire economic and public safety consequences should projections of sea level rise for the

coming decades prove accurate is something else altogether. The Vineyard’s economic base – tourism – could be decimated, business districts jeopardized, and electrical, sewer, water, and transportation systems compromised.

“My personal feeling is people are overwhelmed. They don’t know what to do; they can’t grasp the impact so they just ignore it,” said Elizabeth Durkee, conservation agent for the town of Oak Bluffs and one of the best informed Island officials on the issue. She has been a longtime advocate for more leadership and planning, a sort of watery wake-up call to engage all Islanders. “If ever there was an issue we need to look at long term,

this is it.”

Even if one ignored all the warnings of climate change in recent decades, the fact of the matter is the sea’s advance should not come as a surprise. It’s been rising for thousands of years, but certainly at an increased rate over the last century. The evidence is right there in the historic mean tide charts from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for Woods Hole or Boston, an incremental rise each year, amounting to about a foot over the last century.

“For as long as we have any record of it, we have proof that there has been a gradual rise in sea level,” said Dr. Graham Giese, an oceanographer and scientist emeritus at the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown.

For Giese, the present-day work on waterfronts is less about getting ahead of the rising tides to come and more about coastal communities catching up to the last fifty years of sea rise after realizing that twentieth century attempts to harden or manipulate the shoreline by moving sand around or armoring the coast with abutments and stone rip-rap ended up being temporary measures. It wasn’t always so. Before World War II, he explained, people who came to the region generally didn’t choose to live on the water. Look at Wellfleet, for example, where the main part of town is distant from the waterfront, or even in Provincetown, where houses tended to be built on the land side of the road, not the water side.

“It was never a good idea,” he said. “It wasn’t a good idea then. It isn’t a good idea now. People knew that.”

People, at least those looking to purchase real estate, apparently know it again. Earlier this year, data scientists from the nonprofit First Street Foundation and Columbia University released some troubling findings from a study of 2.5 million coastal properties in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Maine. Tidal flooding from sea level rise has eroded relative home values by more than $403 million during a twelve-year period ending in 2017. Massachusetts was hit hardest, with coastal homes losing $273 million in value over that period. Barnstable, on the Cape, was among the top five hardest hit towns, losing about $16.5 million. Two Island towns were also in the searchable database: Vineyard Haven, which it said has lost nearly $990,000 in home values, and Edgartown, about $651,000.

No question, said Giese, there is real reason to worry about accelerating sea level rise in the coming years. But referring to the NOAA charts, Giese said: “You should keep that in front of you and realize it’s nothing new.”

It’s certainly not new to Steve Ewing. He has worked in and on Island waters for fifty years, most of them through his own business, Aquamarine Dockbuilders, tending to almost all of the piers in Edgartown as well as many others around the Island. That includes the Edgartown Yacht Club, which he has helped maintain over the years, and where he acted as a consultant for the recent renovations.

“I don’t think anyone has seen sea levels go down,” he said recently, in a typical piece of understatement.

Just down the harbor from the yacht club is the Vose boathouse, an iconic wharf and building that has stood sentry for 120 years. This spring Ewing’s company and a few other contractors raised the boathouse’s deck a foot higher. It was an involved process that included shifting the entire building onto the beach’s edge while the pilings were replaced.

“It’s not rocket science – water’s coming up, you know?” said Ewing. “You don’t have to read a book or anything. You don’t have to listen to the news to see what’s going on.”

For the man who has worked on the waterfront virtually his entire adult life, it all comes down to a calculation informed by his experience and data about sea levels. Ewing also happens to serve as Edgartown’s poet laureate and is the kind of person who pays attention to the details of nature around him. In particular, over the decades he has kept a watchful eye on where the barnacles choose to call home.

They will latch onto piers, pilings, and sea walls just under the mean water line, he explained, and they have been slowly, relentlessly moving up higher over the years. “I swear by it,”

he said. “It’s right there in front of your face.

“I didn’t see ice caps melting, the friggin’ polar bears becoming extinct, and all that shit,” he said, laughing. “But I saw – just common sense – things had to be higher in exposed areas. I started with that, and as we rebuilt all the piers in the harbor, I watched where the barnacles were.…”

More than once he had to persuade customers to build higher than they wanted, but he’s glad he did. If he hadn’t, he said, “where they wanted me to build would be under water.”

Throughout last fall, winter, and into the spring, the yacht club work attracted gawkers intrigued by the sights and sounds of demolition, pile-driving, and the grunts of a five-story crane wrestling giant steel pilings.

After a series of hydraulic lifts had jacked up the cavernous clubhouse (including its interior walls), work progressed below. Approximately 110 old wood pilings were replaced with forty steel “pipe” pilings, half of which are eighteen inches in diameter, the other half twelve-and-three-quarter inches. For each, a fifty-foot-long section was driven into the harbor bed, then another fifty-foot section was welded on top of it, and finally the whole thing was driven down to a so-called “point of refusal” – about seventy-five feet below the harbor bottom. Steel I-beams were laid on top of the pilings, length- and crosswise, to create the foundation of the new, improved Edgartown Yacht Club resting atop a slightly higher perch. Finally, the old dining room was dropped ever so gently back down on top of the higher deck. New, polished ipe (pronounced ee-pay) wooden floors were laid down, the old bar was reinstalled, and the silver service cabinet moved back into the building.

Truth be told, the place was due for a renovation, and the new building includes a new kitchen and office spaces. It would have been senseless, however, to upgrade in situ. “Okay, while we’re at it, we know there’s greater issues that we have to address too,” said Roman. “We knew we’re going to raise it. I’ve been here thirty years; it’s been flooding for thirty years. And what could we do to mitigate it?”

As it has in the past, the club will doubtless still have to weather massive storms and floods, such as the 1938 hurricane when the club was said to have water splashing against its roofline. Or the one in 1944, when the wind gauge broke at the Naval air station (now Martha’s Vineyard Airport) and the 116-foot yawl Manxman tore from its mooring, crashed into the dragger Priscilla V, and ended up wedged onto the finger piers between the Coal Wharf (present-day site of The Seafood Shanty restaurant) and Osborn’s Wharf (the yacht club’s location).

Among the most destructive storms was Carol in 1954, which, according to the club’s official history, saw two employees barely escape injury, working in knee-deep water when the windows came crashing in and the doors were blown off. The club’s upright piano washed up on Lighthouse Beach, the old oak bar and blue deck chairs floated up Main Street.

But as for the future of inexorably rising seas, Roman is now guardedly optimistic. “We challenged the engineers here,” he said. “We’re going up two feet now. What happens if we want to go up another two feet fifty, sixty, seventy years from now? How does that work?”

In the case of the yacht club, the I-beams can be cut from the pilings and moved up.

The parking lot, however, may well be quite damp.