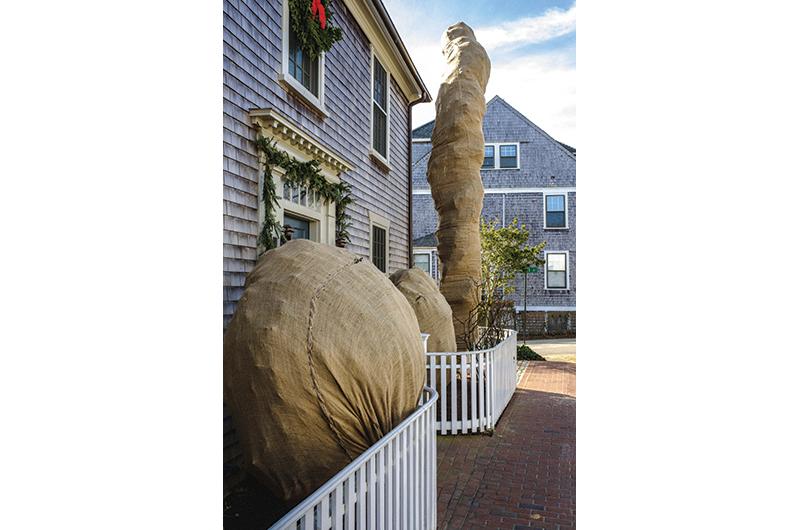

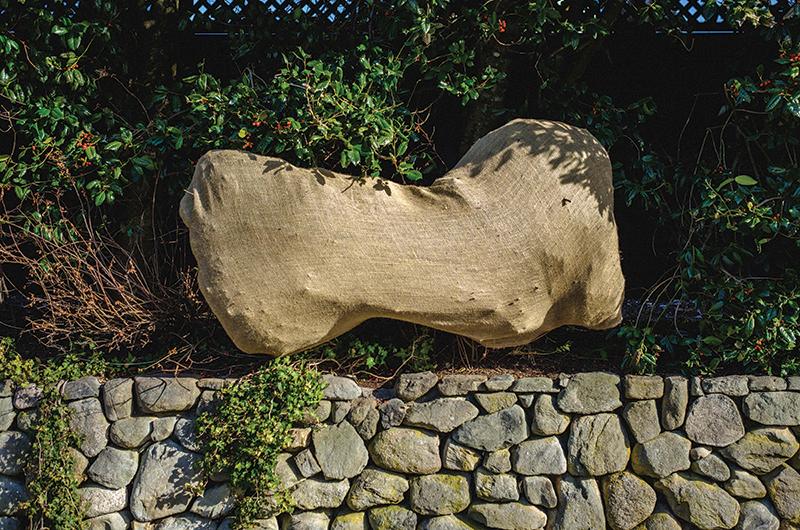

Drive through the still streets of downtown Edgartown on a winter morning and you’ll see them: dozens of shrubs and trees wrapped in burlap. Here, running along Simpson’s Lane, is a formidable flat-topped barricade, high as a moat’s wall. There, on Summer Street, flush against the façade of a handsome clapboard house, is what looks like an enormous dog bone, or a barbell; on closer inspection it’s three short shrubs, side by side, wrapped as one bundle. Next to it, an enormous sarcophagus (a holly tree, it turns out) leans against the house. And there, a high hedge, made up of shrubs that have been individually tucked in at the bottom, looks like a row of giant molars. Huge caterpillars -– low-lying rows of covered-up dwarf boxwood – are everywhere. More billowy, freestanding evergreen bushes look like lumpy, clumsily wrapped Christmas presents.

Hello, why are the plants all wrapped up? What’s going on here? Has a Christo acolyte – or who knows, Christo himself – made a stealth trip to the Vineyard? Why didn’t anyone tell us he was here? Or is there something wrong with the plants? Is the burlap a giant Band-Aid, swaddling them because they’re sick?

No, they’re not sick at all. In fact, keeping them from getting sick is what wrapping these evergreens is all about. Off-Island, the practice of burlapping evergreens is becoming increasingly popular: in the Hamptons landscapers seem to have run amok, wrapping every evergreen in sight; and Martha Stewart battens down virtually every tree and shrub on her Bedford, New York, estate. (Take a look at her blog if you doubt it.) Here on the Vineyard, however, some experts and landscapers feel that wrapping trees and shrubs is over-coddling. Others say that if a client can afford it, and if the trees and shrubs are particularly vulnerable, wrapping can be a good way to go.

“There’s no right or wrong,” says ecologist Todd Rounsaville, who serves as curator at the Polly Hill Arboretum in West Tisbury. “We don’t have the time or resources to baby things here, but if it’s a high-dollar client, I’d probably be doing the same thing.”

Many of those clients live in Edgartown, and many favor boxwood. The dense, dainty-leaved evergreen shrub is ubiquitous in that town, where fastidious lawns and gardens often feature it trimmed into plump, shapely spheres or planted in tall orderly rows or as low-lying borders and frames for gardens. English gardens abound in boxwood, and Donaroma’s, the forty-one-year-old Edgartown nursery and landscaping company, whose garden designers specialize in an English “look,” design and tend to many of them. (Not all boxwood planted by the nursery is, technically speaking, English boxwood; other varieties include American and Korean boxwood.) Donaroma’s wraps for clients elsewhere as well – downtown Vineyard Haven has plentiful boxwood plantings, and Chilmark has some – but boxwood is used less beyond Edgartown, particularly up-Island. Edgartown is the boxwood epicenter of Martha’s Vineyard.

“They’re an important part of the landscape,” says Kate DeVane, landscape designer and maintenance coordinator at the nursery, “but they can be fragile. That’s where the wrapping comes in.”

On a chilly December morning, DeVane, who has worked at the nursery for twenty-two years (and in her off-work hours runs the Island Autism Group), visits a handsome Greek revival house on Fuller Street. There, a Donaroma’s crew of three is finishing wrapping several rows of trimmed, rounded boxwood that rim a small front courtyard.

The experienced crew works deftly, using staple guns and thick staples to fasten together the seams of the burlap, making sure that they are in the back of the plants, facing the house, rather than the street. They’ve wrapped single layers of the burlap tautly and snugly – but not so snugly that branches will rub against the burlap, which damages the fabric, or so loosely that the burlap will flap around in the wind. Several crews do the wrapping for about sixty-five customers every late fall or early winter, after other fall landscaping chores are finished. (Some seasonal clients who come for the holidays request that the wrapping not be done until they’ve left.)

“Burlapping is really an art,” says DeVane, who later drives by a house outside the village where the seams of the burlap on shrubs have been secured with notched plastic trash bag ties; the homeowner isn’t a Donaroma’s client. “They look like Chucky,” from that horror movie, she says. (At the other extreme are labor, and cost-intensive, hand-stitched seams, the sort that Martha Stewart insists upon.)

One reason to burlap is to prevent the damage caused by snow loads. Here at the Fuller Street house, for example, some of the boxwood shrubs are in the line of possible mini-avalanches – snow that slides off the roof after a serious snowfall. The wood in boxwood isn’t particularly strong. “All the snow off the roof splits them right open,” says DeVane.

Snow kicked off by snowplows, or simply a heavy snowfall that dumps heaps of wet snow on top of the shrubs, can also hurt boxwood – particularly young or recently transplanted shrubs, but also ones that have been in place for years. “A row like this,” says DeVane, pointing to a boxwood border on the Fuller Street property, “that’s been in for five to ten years, you want to make sure one [shrub] doesn’t die.” One dead shrub in the row would be as appealing as a missing tooth in a grin, and boxwood are slow-growing, not easily replaced.

“If one boxwood in the row dies, it can take years to grow and prune it to perfectly match the ones that have been there for years,” says DeVane. “And boxwoods are really expensive – it’s not like replacing a rose bush.”

Burlap bundling keeps the boxwood from splitting, but the fabric also provides a kind of ongoing moisture delivery system. “The snow falls onto the wrap and then the snow leaks through the burlap,” says DeVane. The loose weave of the burlap and the fact that burlap is a natural fabric (it’s made from the fibers of the jute plant) allows it to “breathe” and creates “the perfect scenario,” says DeVane. “The snow is able to sort of drip through as it’s thawing – you’re getting more moisture and preventing [the plant] from getting dehydrated.”

But the threat of crushing snow loads isn’t the only reason Donaroma’s wraps evergreens, says DeVane, or even the main one. Stiff winter winds encourage evergreens to release, or transpire, moisture from their leaves faster than their roots, way down

in the frozen soil, can replenish it.

And winter winds here on the Vineyard carry an additional drying – or, in botanical language, “desiccating” – agent. “The wind dries everything out,” says DeVane, “and then of course the wind brings in salt spray. It’s pretty amazing how far from the water you can be and still get salt spray; some of the in-town houses in Edgartown can get it. If you’ve been here after a hurricane, you can see some of the damage way in-Island.”

“The salt is particularly drying,” says Mike Donaroma, owner of the nursery. “It’ll pull the moisture out of the leaf.” Salt used to maintain winter streets can also find its way onto plants. Dried-out leaves won’t kill a plant, but they look bad come spring and take years to grow back.

“The main reason we’re wrapping is to prevent salt spray and dehydration,” says DeVane. Evergreens with needles are less susceptible to this desiccation, at least here on the Vineyard, but boxwood and holly, both leaved evergreens, are particularly vulnerable. “The leaves of evergreens get really, really dry, and boxwood leaves are little,” she says.

Wrapping is “really important with the hollies,” says Donaroma, notably first-year ones with their new, still-developing root system. “They have a big flat leaf, and if the ground is frozen the roots will have difficulty pulling up moisture to the leaves.” (The wild American holly trees native to the Vineyard are a different matter, Rounsaville points out. “If they’ve seeded themselves, they’re pretty tough.”)

Other leafy evergreens on the Vineyard don’t seem to require special protection. “Rhododendron and azaleas do beautifully on M.V.,” says DeVane, as do arborvitae. “They don’t need to be wrapped.” But deer love nibbling arborvitae leaves and yew needles, so Donaroma’s often uses netting to dissuade deer from eating these trees, which the company otherwise doesn’t habitually wrap. “The yews and arborvitae are tough,” says Donaroma, “but they don’t like deer chomping on them.”

Burlapping is often recommended to shield evergreens against winter sun damage, known as winter burn or winter scorch. Like salt spray, a combination of bright sun and cold, dry, windy weather can make foliage transpire faster than its roots can draw moisture from the frozen ground. But DeVane and Donaroma say that winter sun damage isn’t a problem here for most evergreens, with a few exceptions. “People are using cherry laurel; they have a big fat leaf and tend to scorch a lot,” says Donorama. He feels that the plant, which is native to southwestern Asia and southeastern Europe, is too sensitive for the Northeast climate, but clients like its glossy leaves and sweet-smelling white flowers in spring. “If somebody requests cherry laurels, I’ll insist on wrapping them” – and not just when they’re young or newly planted. “I’ll wrap them forever,” he says.

Generally, “it’s the wind that’s going to burn the foliage,” not the winter sun, says Tim Boland, executive director of Polly Hill, “but that does happen, particularly with plants that are fully exposed.”

When they’re out in the full sun, the leaves themselves become softened, especially in the morning. They lose more moisture as the winds pick up. “It doesn’t always kill the tree, but it looks like hell. It browns completely, like it’s been hit with a blowtorch.”

Boland and his team will sometimes shroud new or rare trees and shrubs – ones accustomed to lower latitudes, for example – with a burlap “house,” a bamboo and burlap structure, or shield them from buffeting winds with a burlap “wall” to see them through the first two or three winters. “Once they’re established they’re left to go on their own,” he says. “They seem to adapt better that way.”

Paul Mahoney, owner of Jardin Mahoney in Oak Bluffs, shares Boland’s outlook. “My personal feeling is if you’re planting something that requires extra attention for the first year or two, then maybe you want to help it,” he says. “If you’re planting something that’s marginal for hardiness or very exposed wind-wise, sometimes it’s a good thing to do.”

Botanist and landscaper Alicia Lesnikowski agrees. “I can see people thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I’m not burlapping my evergreens.’ In general people shouldn’t worry about that on the Vineyard…but if you’ve got a lot of wind, if you’ve got salt spray, you might consider it.”

Peggy Schwier, who has been designing gardens on the Vineyard for more than thirty years, will also use occasional burlap protection – a tepee made from stakes and burlap, or a burlap wall – but says she doesn’t use many evergreens in the first place.“I don’t plant a lot because they’re not really native,” she says, admitting that she prefers a natural look. Occasionally she’ll use varieties that she feels are sturdier, among them inkberry, Ilex crenata, and white pine. She also will use deciduous trees and shrubs suitable to a specific site and to the Vineyard’s climate. She quotes a gardening adage: “The right plant for the right place.”

For those not inclined to wrap, proactive planting is the best idea. Ideally, plants at risk of winter damage should be planted in areas not buffeted by wind or subjected to too much direct sun; the north and east sides of buildings, for example, can be best. And newly planted or transplanted plants should be well watered as they head into winter.

One reason experts are wary about wrapping is a certain trickiness about when to remove the burlap. If you leave it on too long “you can get mice or voles,” says Boland. “This is a nice condominium for them, particularly at the base of the plant. They eat the bark of the plant, and sometimes the root stems as well.”

Plants also can overheat if the burlap is left on too long or pulled off too soon, which DeVane readily acknowledges. “We have winter and summer, we don’t really have spring here,” she says. “You have to be very careful, a plant can bake inside its burlap. But if you take it off too soon and then you get a winter storm, the thing you’ve been preventing all winter long with the wrapping can occur in March.”

DeVane feels that wrapping is worth it, and that Donaroma’s doesn’t wrap indiscriminately. “Certainly there are some shrubs that have been in Edgartown for fifty years that don’t need to be wrapped because they’re fully acclimated,” she says. “We wrap things depending on how delicate they are, how long they’ve been there, and where the site is. So last year, for example, we had a site on Edgartown Bay Road that was all newly planted. That site” – next to the ocean’s stiff, salty winter winds – “is extremely tough. When you plant anything right on the water like that, you have to either wrap it or you have to be prepared for some Dr. Seuss-ing of the plant material. It develops weird shapes.”

To illustrate her point, DeVane drives to the site. The large, newly renovated house has a commanding view of Katama Bay. Large holly shrubs, trimmed into giant gumdrop shapes, and Hinoki, a slow-growing, expensive cypress, surround the house. All were planted only last summer; all are carefully wrapped. Other recent plantings, like several Hollywood juniper trees, are not. “These don’t need to be wrapped,” she says. “They’re really tough.”