Dump picking, an Island tradition still practiced today in more civilized form at the aptly named Dumptique in West Tisbury, once involved climbing through chest-high mounds of rotting garbage, broken glass, water-filled tires, and plastic tatters across a foul-smelling moonscape fiercely guarded by shrill seagulls. But that didn’t seem to stop many. Occasionally, genuine treasures could be found.

The late Basil Welch of Vineyard Haven, my childhood neighbor and a self-described dump picker, found lots of gems in the Island dumps – hand-cranked Victrolas, kerosene lanterns, silverware. But his most-prized discovery occurred when he was a young man trolling the dump in 1950.

“There was a man that lived in North Tisbury – Middletown – whose name was Ed Lee Luce, and he raised poultry and stuff, but he also was a photographer,” Welch told oral historian Linsey Lee of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in 2002. “He died eventually, his house was sold, and the people that bought the house cleaned everything out and they threw it in the dump in West Tisbury. I happened to be at the dump probably soon after they left and I picked up three or four hundred of those

old glass negatives.”

Decades passed before Welch dug the boxes out and began to develop the negatives with the help of my grandfather, Harold Stanton Lair, who lived with us across the street. Often still in his phone company work outfit, Welch would park himself in a chair in my grandfather’s room nearly every afternoon to light up a smoke, chew the fat, clown around, and then get serious about old Vineyard photos. He had a droll but merciless wit and that old Island accent, more down east than Harvard Yard. My grandfather referred to himself as Stan, but Welch used his other nickname, Hun, a gentle mocking of my long-dead grandmother’s slightly henpecky term of endearment for him. Welch gave me a homemade wooden nickel once – the ones you proverbially aren’t supposed to take – and nicknamed me Chunk after the swamp in the Oklahoma section of Tisbury, where my ancestors once lived. My family kept a darkroom in our cellar, into which Welch and my grandfather would eventually disappear for hours making black-and-white prints. I didn’t know it at the time, but many of the images they printed were made by Edward Lee Luce.

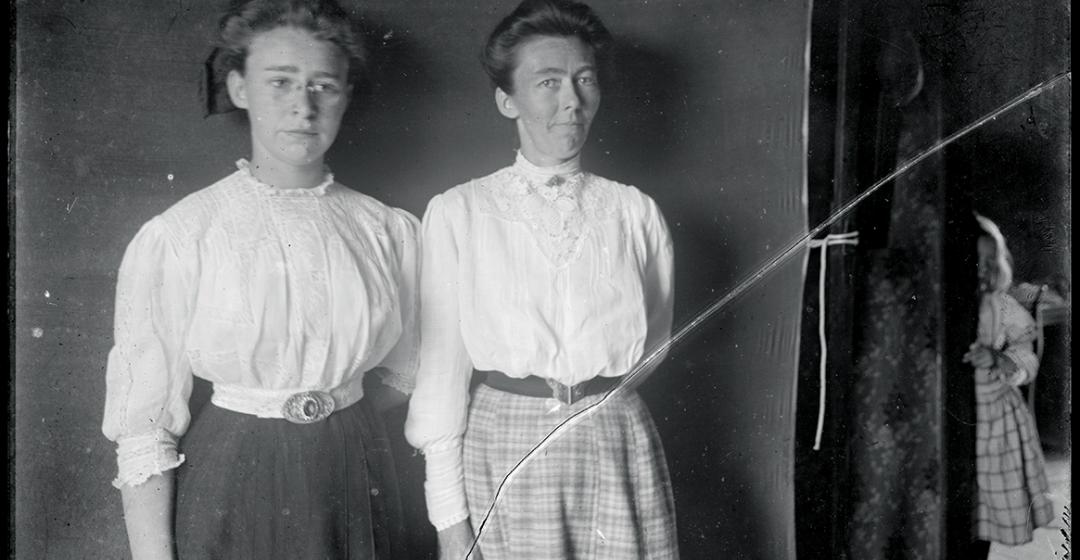

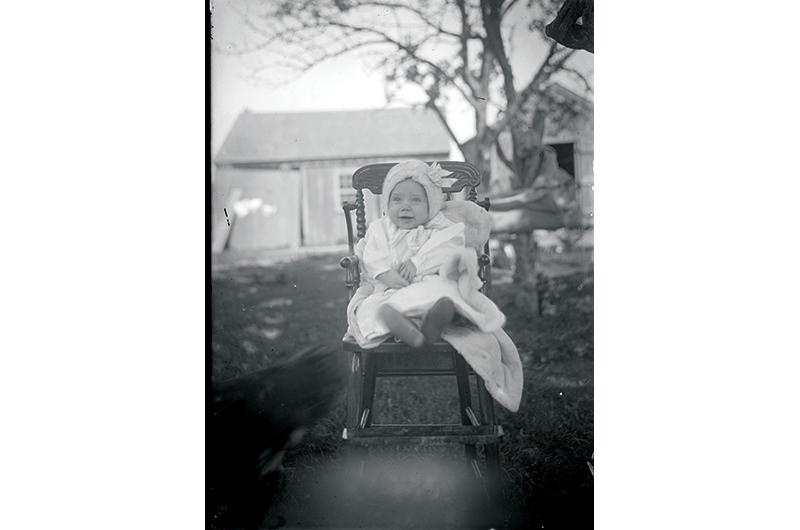

What slowly emerged from the basement was a mix of formal portraits, serene landscapes, documentary architecture, and playful observations of people and animals. Luce loved photographing children, workmen, babbling brooks, bicycles, and especially animals – cats most of all, but also dogs, chickens, oxen, goats, and horses. He photographed weddings and pageants, beaches and bridges, families, prize horses, the rich, and the poor. He photographed two dead men laid out in their caskets, one of whom may have been his father, bearded blacksmith Charles Henry Luce, who died in 1917 at the age of seventy-three.

Though some of the old prints Welch and my grandfather produced in the basement now belong to me, some ten years before his death in 2011 Welch donated the glass negatives to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, where the glass plates reside today. (Additional donations were made by his daughters in the following years.) With help from the online library Digital Commonwealth, last year the entire collection – more than one thousand images – was digitally scanned and made available to the public at digitalcommonwealth.org.

Looking at all the images together is like taking a trip through a lost world, and it made me wonder about the man who made them.

Edward Lee Luce was born on July 18, 1879, in West Tisbury, then still a part of Tisbury, although his birth went unrecorded by any town. He was named after his grandfather, who had been lost at sea off Virginia twenty years earlier with three other Tisbury mariners. Luce was the only child of Charles Henry Luce, a West Tisbury blacksmith and day laborer, and Sephrina West, a Chilmark-born dressmaker whose first marriage to Chilmark whaler James Hancock had ended in divorce.

Divorce was uncommon in the nineteenth century, but it was not the most unusual thing about West’s background. One of eight children, her next older sibling, Rebecca, had changed genders and become her brother William in 1850. Her next younger sibling, Mary, subsequently became her brother Luther.

Newspapers across the country reported William’s story. The Milwaukee Sentinel and Gazette wrote, “VERY STRANGE. – A petition was recently presented to the Legislature on the part of an individual in the town of Chilmark, stating that he has a child fifteen years old which was born a female (apparently) and christened Rebecca, but that recently it has manifested itself to be of the male sex. He therefore petitions that the name of this androgynous offspring may be changed to William. It is stated that this account is perfectly correct, and that the instance presents the most curious cases in physiology, Truth is stranger than fiction.”

The Massachusetts legislature accepted the petition, and Rebecca legally became William in April 1850. Mary’s transition to Luther, a few years later when she reached her teen years, was less formal; no legal petition was ever made. But in a 1939 affidavit recorded at the Registry of Deeds in Edgartown, Malvina Norton of Chilmark formally declared that she “well and truly knows that the said Luther B. West, as a child, was known as Mary A. West.... Luther B. West went to school with her older sisters, and was thought to be a girl and was named and called Mary A. West. When Mary A. West was in her teens her name was changed to Luther B. West and she was thereafter known as a male. Mary A. West and Luther B. West were one and the same person.”

Luce’s uncles, William and Luther, left the Island as young men at the close of the Civil War, and both married women, but remained childless. William became a Bridgewater farmer and wood dealer and later a successful real estate broker in Quincy. Luther moved to Taunton and founded a silver plating company, and later had a second-hand furniture business.

When Luce was ten years old, the family moved across the neighborhood into a house on what is now State Road in North Tisbury. Tradition holds that the home, which today belongs to Adam and Lisa Gross, was built in 1838, although like many homes of the era it may have been moved here from another site. The property had been purchased in 1863 by John Williams, a black man born in the Deep South who was presumably a former or fugitive slave and who had recently married Priscilla Bowes, a Wampanoag woman from Gay Head. In 1889 the family sold it to Sephrina West, Luce’s mother.

The Luces added a kitchen in 1896. (Neil Withers reports finding copies of the New Bedford Mercury of that year stuffed in the walls.) And below a room located just beyond the kitchen, the root cellar would have made an excellent darkroom.

Luce attended the Locust Grove School on Indian Hill as a child, and later the school in Vineyard Haven. According to his obituary, he was “one of the boys who hung around with his elders at mail time.” In those days the mail stages usually changed horses at what is now the Bananas clothing store in North Tisbury, which was then called Middletown. It was roughly a halfway point on the long drive down-Island in the morning and up-Island at night.

“Neighbors from miles around gathered at the post office, kept by Thomas Merry and later by Lillian Adams,” the obituary continued. “Many of the old people came through the ‘back road,’ which emerges at this point to join the present State Road, and others walked across lots and came through what was then the church yard. While waiting for the mail stage, the men and women would sit around and talk, and there were good tale-tellers in the group.”

Once out of school Luce held many occupations, all in North Tisbury. As a young man he worked as a baker, and later in life as a magazine salesman. He would occasionally pick up jobs as a laborer on village building projects, riding his motorcycle or bicycle across town. In the late 1920s Luce became the West Tisbury tax collector and was the envy of taxmen across the Island one year when he managed to collect all but $5 from the nearly $8,700 owed by West Tisbury residents.

Luce was also a talented fortune-teller. His obituary noted, “Mr. Luce for many years carried on the profession of palmistry and clairvoyance in one form or another, at first touring with fairs and similar public shows. He had a tent that he used for the purpose. But the present generation had known him at his home in North Tisbury and through his advertisement in the Vineyard Gazette which, over a long period, occasioned a good deal of comment.” One such ad in the Gazette in 1940 read: “Your Question Can Be Answered. Love, Business, travel, by Astrology, Card Reading, Palmistry. Instructions given. Edward Lee Luce, North Tisbury. Hours 1–5 p.m. and by appointment.”

Fortune-telling in 1940 was a booming business, not only in North Tisbury but nationwide. Usually but not exclusively performed by women with exotic stage-names such as Madame Zara inside tents decked with trappings suggestive of Gypsies, fortune-tellers made up a multi-million dollar national industry that included palmists, astrologists, card readers, psychics, numerologists, and other occult science entrepreneurs. Diana Hawthorne’s 1937 book The Complete Fortune Teller was a runaway hit as nervous Americans began studying horoscopes to predict a rising Hitler’s next moves. The practice was controversial, however, and astrology was outlawed in many of the larger cities. Swindling was rampant. A Massachusetts law still on the books requires fortune-tellers to be licensed by the town, and to be town residents for at least twelve months before applying, in the hope that actual Gypsies would be deterred from applying. Another extant law equates “pretended fortune telling” with larceny.

![A farmer poses with his cart and a yoke of oxen at the Ellsworth Norton Farm on [Old] Courthouse Road in West Tisbury.](https://mvmagazine.com/sites/mvmagazine/files/styles/mvg_large/public/article-assets/main-photos/2018/luce_photo_3.jpg?itok=cNpPtDz2)

Luce also raised poultry to the extent that he earned the nickname Chicken Luce. But the name didn’t last. As my grandfather, who was born in Vineyard Haven in 1902, once explained, “In those days, the night before the Fourth of July was a big event. We were allowed to stay out all night on that night, and people just raised the dickens. Tip over outhouses. In fact we tipped over one one night, and the guy was in it! Drag wagons around and put ’em on roofs, and all that sort of stuff. I recall one night before the Fourth, a couple of us put a barrel up on top of the schoolhouse flagpole.”

The night before one July Fourth, a group of rowdy Middletown kids turned over Luce’s outhouse. Afterward, as the outhouse needed shingling anyway, Luce decided it would be easier to work on it while it was still on its side. When he finished, after getting the help of a neighbor to stand it back up over its pit, it was discovered that Luce had nailed all the shingles on upside-down. From that day on he was known as Butts-Up Luce.

Only during the 1910s and early ’20s did Luce list his principal occupation as photographer. “Photographs,” read a 1919 ad he placed in The Vineyard News, a short-lived Vineyard Haven newspaper, “Taken at Your Home by an Experienced Photographer. Exterior and Interior Views / Marine and Landscape / Photographs of the Family. Appointments to any Part of the Island.”

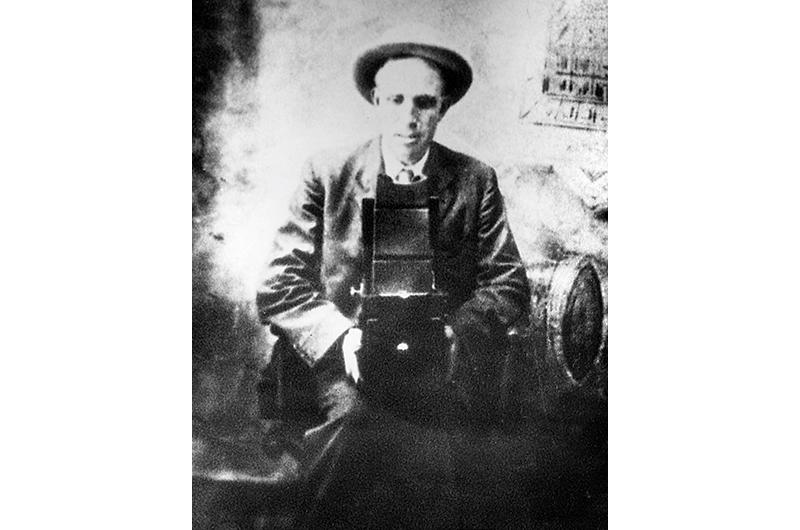

Luce’s collection – now in the hands of the museum – is about 60 percent 4 x 5 glass plates and 40 percent 5 x 7 glass plates. From the one undated selfie we have of Luce, with his camera in hand, it looks like he probably used a Graflex, sometimes referred to as the first single lens reflex (SLR), popular among both photojournalists and fine art photographers of the period for its light weight, ease of use, and ability to freeze action.

The process he used to develop his negatives has changed little in a century. In a darkroom he would have immersed his glass plates in a series of chemical baths: a developer (probably toxic pyrogallic acid, or pyro, tempered by sodium carbonate or “washing acid”) would make the latent image visible in metallic silver. After a rinse he would follow with a bath of fixer (hyposulfite of soda, or hypo) to remove the unexposed silver salts, followed by another wash, and then several hours of drying. Finally he would expose sensitized paper to light through his plates to make 4 x 5 and 5 x 7 prints, or in an enlarger to make bigger prints.

His photographic collection seems to peter out in the 1920s, but its earliest plates date to the early 1880s – before he could lift a camera, let alone produce professional photographs – suggesting that he may have been a collector as well as a photographer. His work was rarely attributed, when it left his clutches at all. His name doesn’t appear in any of the contemporary compilations of American photographers produced by the National Stereoscopic Association and others.

Luce eventually became one of the Middletown elders he hung around with in his youth, holding court at what was once the North Tisbury Post Office but had since become Maud Call’s general store. The fact that he was a fortune-telling, motorcycle-riding, chicken-loving, camera-wielding oddball didn’t lower his stature in the eyes of those who would inevitably gather there. Then as now, the Island was a relatively tolerant place. In an interview with the Dukes County Intelligencer, long-time summer resident Margot Wilkie remembered, “A man called Ollie Borgen lived ‘in sin’ with Mrs. Call. Nobody paid any attention to the fact that they weren’t married. I mean that was one of the nice things about the Island.... North Tisbury was a place of sin, we were told.”

Luce never married, but took care of his aging mother at home until her death at the age of eighty-seven in 1927. To make ends meet they took in boarders. Charlotte Henderson, a widowed Wampanoag octogenarian (listed as “black” in most censuses), boarded with the family at the turn of the century. William Luce, a divorced, middle-aged trap fisherman (not a close relation), lived with them next. Their longest-lodging and last boarder, living in Luce’s home long after his mother’s death, was Henry Norton.

Remembered with affection as “simple-minded” by his relatives today, Norton was a talented granite worker who was able to independently support himself through hard work. His stone craftsmanship can still be found throughout town.

The 1930 census lists the two fifty-something men living alone together in the old house on State Road, but when Norton eventually became infirm he moved off-Island to live his final months at the State Hospital in Taunton. Although Luce became close with his neighbor, carpenter Forrest Bosworth, he spent the rest of his years alone in the old house.

At the age of seventy-one, after a short stay at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, Luce died in October 1950. In a will he had written a few years before his death, he bequeathed his entire estate “to the Town of West Tisbury to be used as the voters of the Town shall determine.” He added pointedly, “I intentionally omit to provide for any of my relatives.”

Who were the relatives he chose to “intentionally omit” from his 1947 will? His parents and all his uncles and aunts were long gone. One of his first cousins, Arthur Dexter, had been lost at sea like their grandfather before Luce was born. He had a few surviving farflung first cousins living off-Island, relations he may have had little contact with. His probate lists only two living next-of-kin they could find – his first cousin Mabel Peckham, a never-married retired schoolteacher living on Long Island, and Walter Dexter, a colorful Mattapoisett marine mechanic who wasn’t even a blood relative (he was Luce’s aunt Katie’s nephew by marriage).

Walter Dexter was curiously like Luce, however. Almost exactly the same age, he, too, was a lifelong bachelor and talented artist. Photography had been his hobby from the age of sixteen and, according to the Boston Globe, he had “built up a priceless file of glass plate records of old Cape Cod before 1920.” So why would Luce choose not to bequeath his photographic collection to his relative in Mattapoisett who had such similar interests, and instead risk his plates being lost in the dump forever? Was it professional jealousy? A boyhood grudge? Or was it just that he felt closer to his friends and neighbors in North Tisbury than he did to any off-Island relations?

After Luce died, his house and its contents were sold at auction for $4,400, and after a vote at town meeting to accept the proceeds, the money was deposited in West Tisbury’s general fund. The irreplaceable glass negatives, on the other hand, went to the West Tisbury dump.

But thankfully, so did Basil Welch.

A link to the complete collection is at mvmuseum.org/photographs.php.