I generally do my best to avoid situations where I might encounter creatures that are mean and have the potential to inflict bodily harm – hunting Cape Buffalo or shopping in a mall the day before Christmas. The exception is fishing for bluefish.

Pomatomus saltatrix, which is Latin for Cuisinart with fins, is as ornery as anything that swims in Island waters. Combine the attitude of a Mad Max biker and the blue’s notorious appetite – it didn’t acquire the nickname “chopper” by accident – and you have a species that provides sheer action for anglers of every skill level in a variety of circumstances.

The striped bass is the premier game fish of the Island, but big bass feed most actively at night and a serious pursuit requires a degree of skill and a dedication to prowling the beaches at hours when sane people are in bed. Blues, on the other hand, are inclined to hit a lure when the sun is up, which is convenient for less dedicated fishermen who like to sleep late.

Schools of bluefish migrate up the East Coast in the spring, following herring, mackerel, squid, and sand eels. In Island waters the major catalyst is the schools of squid that move into Nantucket Sound in order to lay their eggs.

The first bluefish generally arrive on the Vineyard by early May – Mother’s Day is my benchmark date – and continue to arrive in what is known as the spring run throughout June. They reveal their presence to sharp-eyed fishermen by the oily slicks that rise to the surface of the water when they are feeding. A slick may be the size of a putting green or a football field, depending on the number of fish. Discounting a false positive attributable to a human swimmer basted in suntan lotion (or buttered popcorn tossed into the water to attract gulls and create a sheen as a joke to throw off the friends following you down the beach), a slick within range is a sign that announces: cast here.

One June afternoon I was driving from Edgartown to Vineyard Haven along State Beach when I spotted a small slick just past Bend in the Road Beach. I parked and rigged up an eight-foot spinning rod that I consider essential seasonal vehicle equipment. As I retrieved a small popping plug, a bluefish of about three pounds attacked it with such vengeance that lure and fish went sailing into the air.

The first fish I landed disgorged a belly full of squid. It was a wonder it could even move. The action continued unabated for forty-five more minutes until the tide slowed and the fish disappeared.

A discerning eye is not required to spot blues when they are engaged in a blitz, the term used to describe the feeding frenzy that occurs when a school of fish encounters a school of bait. The signs are a surface froth of fins, bait, terns, and gulls that skim morsels off the surface but have the good sense not to enter the water. For a fisherman the excitement is infectious.

Many years ago I was a guest at a nice cocktail reception at a home overlooking Duxbury Bay. I was standing on the porch enjoying the view when I saw a dark mass taking shape a few hundred yards off the lawn that was bordered by a salt marsh.

It only took a few moments to realize what was happening. I ran to my vehicle to fetch my waders and a fishing rod.

The dark mass materialized into a school of menhaden, also known as bunker, that were being penned up against the salt marsh by a school of bluefish in excess of fifteen pounds. Suddenly, frantic bunker were jumping onto the marsh grass

in an effort to escape the feeding blues.

I hooked one fish after another. I took one blue and ran back up the hill to the party to describe what was happening and to enlist rookie fishermen. Someone snapped a photo of that moment. I am in waders holding a surf rod and pointing at the beach with a wild expression as my roommate, Bill Stevens, holding a cocktail, speaks to me wearing a look that suggests he thinks I may be completely mad.

The party ended with a pile of big blues in the kitchen sink of the party hostess, who was greatly amused by the turn of events – several guests had pulled in bluefish for the first time in their lives – and my girlfriend in tears over my behavior. On the positive side, I moved to the Vineyard and married an Island woman who accepts and even understands FDS (fishing derangement syndrome).

A cast into a school of feeding blues will almost always produce a strike. Some lures may outperform others, but it is the blue’s aggressiveness that makes it a prime target for fishermen of any age and skill level.

Blues will snap like savage dogs at a quickly retrieved surface lure right up to the beach or boat – the ferocity is enough to give a mailman nightmares. When hooked, expect a fish to catapult into the air, particularly if the water is shallow. It all makes for a great show.

Bluefish can be caught from the shore most anywhere on the Island where there is a confluence of bait and current. Even if your ex got the $300,000 gate key to Quansoo Beach in Chilmark, don’t despair. Go to Wasque Point on Chappaquiddick on a falling tide where more blues are caught per yard of sand than any other spot.

At its height, the falling tide runs very strong along the southeast corner of the Island. The combination of currents and change in depth creates a noticeable seam of churning water that attracts game fish of all stripes looking for an easy meal in the turbulent waters.

The action is often shoulder to shoulder. When fishing among a picket fence line of fishermen during a blitz it is helpful to know the steps to the Wasque minuet. Hook a fish, do-si-do walk the fish with the current, land it, and return to your original spot, which by protocol and custom still belongs to you. Likewise, allow a fisherman with a fish on to walk in front of you while you pause your casting.

If you are a poor dancer and want more space, travel north along East Beach on Chappaquiddick and look for telltale slicks. The area off Dike Bridge is another popular location that is easily reached by foot. Other than a wire leader, there is no need for specialized tackle beyond what the fishing circumstances require. For example, a nine-foot surf rod capable of handling a strong fish would be a good choice for Wasque in order to cast a popping plug such as the Robert’s Ranger, an Island-made beach favorite. A light seven-foot rod is more than adequate when the fish are in Cape Pogue Pond, or when you’re cruising the flats off Eel Pond in Edgartown and have plenty of space to play the fish without annoying fishermen up and down the beach.

Or when you find a nice stretch of South Beach to bottom-fish. Place a fresh piece of squid on a hook attached to a sinker, cast out, and relax in a beach chair. Just be sure the rod is secure in a deeply anchored sand spike or it may disappear in the ocean.

My preferred light tackle casting plug is a green one-ounce needlefish with all trebles removed and a single hook on the end. It is easy to cast into the wind and safe to grasp when attached to a bluefish.

A single hook reduces the risk of one of several things occurring when you attempt to release a fish, all of which will ruin your day: the bluefish clamps down on your finger; the bluefish jumps and you hook yourself on the lure; the bluefish bites you and you hook yourself – ouch.

An orthopedic surgeon I met told me he had treated a fisherman who lost a toe to a big bluefish. I do not know the gory details, but any blue over fifteen pounds would certainly seem to have the strength to do some damage. And how’s this for a tabloid headline, only it appeared on April 10, 1976, in The New York Times: “Ravenous Bluefish Attack Swimmers at Florida Beaches.”

Fish in the twenty pound range were chasing mullet. Christine Schult, eighteen years old, of New Canaan, Connecticut, who suffered severe hand cuts, told The Times: “I really felt I was in Jaws. I was riding the waves at Pompano Beach when suddenly I was surrounded by fish. I was going to run for it but I fell. Right then, a big fish at least two feet long grabbed me and I grabbed him with my other hand and whacked him. It was his eyes. He was looking at me so meanly.”

Mean or not, blues deserve respect for table qualities. Bluefish readily absorb the smoky flavor of a charcoal grill. They are also perfect for putting in a home smoker, such as a Lil Chief or Masterbuilt. Bluefish often get a bad rap, which I think is attributable to poor handling the moment the fish leaves the water.

If I keep a blue for the table, I cut its gills to bleed it and get the fish on ice as soon as possible. If on a beach with no ice available, I place the fish in a moist trench and cover it with damp seaweed to keep it cool.

Respect for the fish encompasses those fish we plan to release. Blues may be tough, but they are not indestructible.

One day at Wasque Rip I watched a visiting fisherman pull a bluefish up on the sand. His kids started dancing and jumping around him in a frenzy, shouting, “Whack it, Daddy, whack it!”

Honestly? There is no need to treat a bluefish like a member of Congress. Hold a fish under the belly and toss it into the water or nudge it into the wash with your wader boot (not your bare foot). The goal is to not injure the internal organs of the fish and preserve your toes.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) manages fish species along the East Coast through state-specific quotas. Recreational anglers account for approximately 80 percent of the bluefish catch, according to the ASMFC.

The ASMFC does not consider bluefish to be overfished, but the data do show an overall decline in abundance. “Total recreational removals peaked in 1986 at 104 million pounds, declined to a low of 13.1 million pounds in 1999, and rebounded somewhat after that to an average of 20 million pounds over the last five years,” according to a 2015 ASMFC stock assessment.

On a positive note, the total numbers and the proportion of fish released alive by anglers has increased over this time period, according to the ASMFC, which states that recreational releases are assumed to have a 15 percent mortality rate.

In the 1980s I took the schools of bluefish I regularly encountered along East Beach in June for granted. I just accepted that I could drive along the beach until I spotted a slick, stop and cast, and catch a bluefish. I was greatly disappointed when that ended. But historically, the size and number of bluefish have always fluctuated.

The Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass and Bluefish Derby, the classic five-week tournament that begins in early September and ends one week after Columbus Day, provides a local benchmark. In 1948, the winning bluefish weighed 4.68 pounds. In 1949 and 1950, five-pounders won the bluefish category, and it was 1955 before a blue exceeded eleven pounds. In 2017, the heaviest bluefish caught in the seventy-second Derby weighed 18.81 pounds.

Fall fishing for bluefish is generally hit or miss when compared to the spring. I suspect it is because bait is more scattered and on the move. I have fished many Derbies when a bluefish of any size from the shore proved elusive, and I have witnessed fishing fortunes change in an afternoon.

In 1992, on the last afternoon of the Derby, a school of big bluefish blitzed about the length of beach from Norton Point to Wasque and East Beach. Even in an age when a text message was something created with a piece of paper and Scotch Tape and stuck to a refrigerator, word got around the Island. When I arrived on a hunch, every third person it seemed was hanging on to a bent rod as fifteen- and sixteen-pounders came thrashing up out of the surf.

That night, when the weigh station opened for the last time in the forty-seventh Derby, big blues were piled up on the fillet station table. Fourteen of fifty-four award positions changed that evening. And Larry Mercier of Edgartown, the town’s highway superintendent and a wonderful gentleman, weighed in a 17.35-pound bluefish to take the shore grand leader spot in a down to the wire finish.

In 1995 Lori Vanderlaske took the shore grand leader spot with an 18.69-pound shore bluefish she caught in Lake Tashmoo. It was quite an achievement, made more notable because she caught the fish on a fly rod and was inspired to try a spot not known for producing big blues by a dream she’d had the night before.

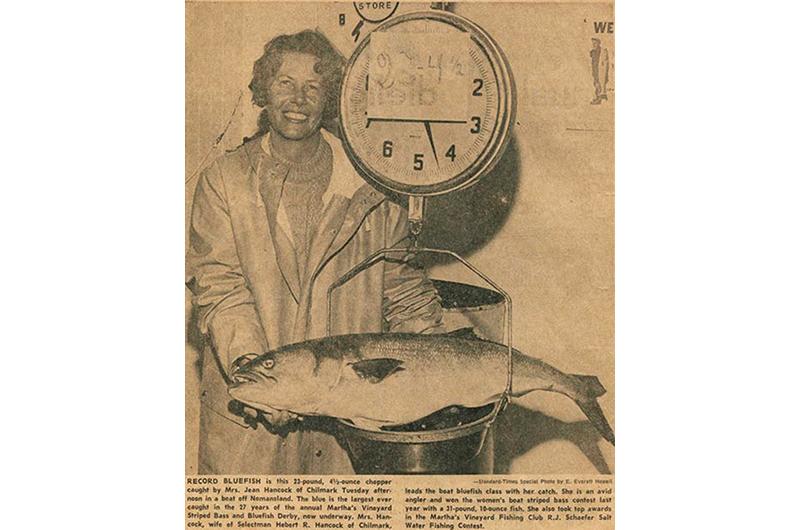

The biggest bluefish ever taken in the Derby was caught by Jean Hancock of Chilmark, who in 1972 caught a 23.28-pound monster from a boat.

If fishing glory is the goal, bear in mind that the Massachusetts state record blue is a 27.25-pound fish caught on September 11, 1982, by Louis Gordon outside Boston Harbor by Graves Light. And the International Game Fish Association record is a 31.75-pound blue James Hussey caught on January 30, 1972, at Hatteras, North Carolina.

This season Island fishermen will pursue bluefish. And dedicated striped bass fishermen, who eschew the use of wire leaders, will rue the bluefish’s presence with grudging respect. In that sense little will have changed in more than a century.

In 1883 writer and fisherman Francis Endicott traveled to the Cuttyhunk Club, just across Vineyard Sound. It was one of many private striped bass clubs, including the Squibnocket Club, on the Island, where men of wealth and privilege caught big striped bass that regularly exceeded forty pounds from bass stands – walkways from which to cast, erected over large boulders along the shoreline.

A local known as the chummer would ladle bits of menhaden into the water to attract the bass. The chummer was also responsible for breaking up the lobster the fishermen used as bait.

“It is true that chumming attracts other less desirable fish,” Endicott wrote of his experience fishing at the club. “Your bluefish has an insatiable appetite and a keen nose for a free lunch. We say this ruefully, as we reel in and put on a fresh hook to replace the one just carried away. Egad! That fellow struck like a forty-pound bass, and cut the line as clean as though he had carried a pair of scissors! What a game fish he is! He fights to the very last and only comes in when he hears that the struggle is becoming monotonous.”