Hidden off a dusty Chilmark road, two modern houses sit on shared land, separated by a thicket of scrub and trees. One is a clean two-story shingled pavilion with vast expanses of floor-to-ceiling jalousie glass; the other, an almost entirely glass enclosure with a roof poised on slender umbrella-topped columns. When they appeared in the early 1960s, Islanders viewed the second house in particular with skepticism: “Looks like a goddamn mackerel trap to me,” fishermen at the Menemsha General Store were overheard saying as the house neared completion. “We should take it out to sea and sink it.”

Fortunately for the young architect who designed it, his girlfriend had a different opinion when she first saw it in 1962. “It was a fabulous experience. It was probably why I married the man,” Lois Wisniewski recalled recently. “It was on our third date, we flew up there and saw that house on the Vineyard and it was just amazing. It blew my mind.”

Like the mid-century homes designed by Eliot Noyes in the previous Home & Garden issue of Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, the two buildings are classics of mid-century modern architecture by influential masters of the craft. Longtime friends and business partners Chester (Chet) Wisniewski and Samuel (Sam) Brody designed the escapes to reflect their deepest aesthetic and social values, and to encourage these values in daily living.

In spite of their overt visual differences, both homes are designed on disciplined grids with flexible open floor plans and abundant use of glass, and both are built of raw, unadorned materials with a carefully exposed structure. The houses work in remarkably similar ways, too, especially in how they promote family connectivity and engagement with the outdoors. Both exemplify the humanism of this second generation of modern architects who were as concerned with their social impact on the world as they were with distinctive form-giving.

Brody and Wisniewski became business partners in 1952, but their paths to practice were quite different. Like many architecture students of his period, Wisniewski educated himself about modern design because it was not taught at his university. Born to working class parents in 1921 in Syracuse, New York, he attended Syracuse University, which had a long tradition of teaching architecture according to beaux arts, neoclassical principles. When World War II broke out, he interrupted his studies to enlist in the Army Air Corps. During those years he read Frank Lloyd Wright’s autobiography and visited Wright’s modern concrete masterwork, the Imperial Hotel in Japan.

By war’s end he knew he wanted to pursue a modern practice, but expediency led him back to Syracuse, where he graduated in 1946. He dreamed of going to Paris to intern with Europe’s foremost modern master, Le Corbusier, but it was financially impossible. He also considered approaching two up-and-coming American modernists who were Wright disciples: the iconoclast Bruce Goff or minimalist Antonin Raymond. In the end he went to the source, traveling to Taliesin West in Arizona to seek an apprenticeship with Wright himself. Arriving uninvited and with an as-yet unremarkable resume, Wisniewski somehow wrangled an interview with the maestro and won the job.

The seven months at Taliesin West turned out to be a pivotal experience – a time when he absorbed Wright’s ideas about organic architecture and how to design expressively with structure and raw materials. He saw his mentor’s rational approach to design, attention to detail, and strict adherence to a grid. He also learned the value of experimentation in the building process: for hours in the Arizona heat, he and his fellow apprentices poured concrete into precast forms for a full-scale structural test model for a theatre Wright was designing. The experiment failed.

In 1949 Wisniewski and three of his Taliesin West colleagues traveled to Redwood City, California, to design and build a spec house of concrete blocks in a veritable homage to Wright. Cantilevered on a two-acre hillside and constructed around a live oak tree, the house they called Midglen required 6,000 hand-poured concrete blocks that the beatniks, as the town folk called them, produced at a rate of 150 per day. Midglen was completed in eighteen months and cost $31,000, which included $1,500 for the land and a $5 per week salary for each designer.

Turning from Wright’s footsteps, Wisniewski briefly pursued Le Corbusier’s, taking a position in Bogota, Colombia, as a draftsman for the new socialist government’s National Buildings Commission. The city had garnered a strong modern identity since 1947, when it commissioned Le Corbusier to design its urban center, a project that took a decade. Wisniewski’s stint was cut short, however. Due to visa complications he returned in 1951 to New York to work for Mayer & Whittlesey, a firm known for massive low income housing projects. One of its principals, Albert Mayer, had recently been chosen to be the master planner for a new town in Chandigarh, India, where Le Corbusier was the lead architect.

Bogota and New York allowed Wisniewski to see the possibilities of modernism at a grand urban scale, but he never lost interest in designing everyday buildings based on the skills he took from Wright’s American studio. In 1952 he formed a new partnership with two other young architects, one of whom was his future Vineyard neighbor Sam Brody.

Brody’s own road to modern practice was more conventional. Born in 1926, he grew up in Toledo, Ohio, and after serving in World War II attended Dartmouth College. In 1950 he graduated from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). In the late ’40s the GSD was in its modernist heyday, with a curriculum taught by a cadre of European Bauhaus masters including Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, who believed a universal approach to design would naturally yield rational, international-style buildings that could function anywhere.

Their approach and style was different from the regional, more eclectic designs promoted by Wright and other American modernists. Still, Europeans and Americans did share certain architectural values, including expressing the connection between nature and building and experimenting with technology and materials. They both believed that modern architecture, in its efficiency and ingenuity (and in the right hands), could solve many societal problems at both the individual and urban scale.

After graduating, Brody worked for Kelly + Gruzen, another New York firm associated with urban renewal. Early on, however, he began to question their approach. “Public housing, as an enterprise introduced following the Depression and the War, was generally accepted as an important social activity,” he wrote many years later. “But, in terms of planning, public housing had become identified with the [European] Modernist view of the tower in the park. And this had been degraded into ‘project’ housing. That meant slum clearance, with the attendant disruption of existing neighborhoods, and then the plunking down of eighteen-story blocks with no reference to their context.”

The intentions were altruistic, but the early buildings lacked solid social or aesthetic innovation. Moreover, as urban renewal schemes they failed, and as a result actually worsened their communities. In this context Brody began to think about better ways to design social housing to improve the lives of their residents. After working with a third like-minded colleague, Lewis Davis, and meeting Wisniewski, the architectural partnership of Davis, Brody, and Wisniewski (DBW) was born.

The DBW partnership lasted nearly thirteen years: an exciting period both in terms of experimentation and public recognition. The partners were all design architects first and foremost, but Davis became the firm’s frontman in pursuit of urban projects, while Brody took on the role of the firm’s most thoughtful and practical planner. Wisniewski, meanwhile, was the artist and experimental craftsman.

Without the political connections needed to work in the public housing arena, their early commissions consisted of houses, schools, and architectural competitions. In time these were joined by larger commissions, such as synagogues and other community-based buildings. DBW’s early work demonstrated the partners’ collective thinking that they could use modern design as a practical, cost effective, humanistic, and aesthetically pleasing way to address their clients’ everyday needs. An open floor plan design for the Green Acres School in Rockville, Maryland, in 1958 featured a generous courtyard enclosed only by walls of glass and a pleated roofline that flooded it with natural light. The design earned them a first prize from the American Institute of Architects Potomac Valley Chapter in school design.

Other awards followed. Their design for the Congregation Beth El in West Orange, New Jersey, completed in 1958, with its dramatic sanctuary created by rising enclosures of glass framed by an intersecting A-framed roofline, won best in its category in the prestigious Patron Church exhibition, sponsored by New York’s Museum of Contemporary Craft. Ironically, it beat out the work of Brody’s former employers Kelly + Gruzen. The Beth El synagogue exhibit was displayed in New York for six months and went on to tour museums across the country for two more years.

The houses DBW designed, meanwhile, were as interesting as their institutional work and even more widely publicized. An environmentally friendly house designed for a large international competition was included in an industry-wide book called Living with the Sun. The Sterling House in Peekskill, New York, 1958, was chosen as one of Architectural Record’s “Record Houses of 1959,” while House & Garden featured it with the headline: “Tree-top living with an ingenious plan.”

“The work of Davis, Brody and Wisniewski habitually rises to the top,” the journal Progressive Architecture said in awarding their 1962 design prize to a home in West Orange, New Jersey. “The jury…invariably comments on the outstanding clarity of the work, the craftsman-like presentations, and particularly the ingenuity and originality of the structural systems. Most of the success of this partnership is due to fine teamwork….”

In 1962 Davis and Brody got the entrée into urban planning they had long sought, garnering the commission for a massive housing project in East Harlem called Riverbend. As was their goal from the beginning of their partnership, the design upended the Le Corbusier model for public housing. A mixed-use complex that incorporated retail at the street level, services as needed, and diverse apartment units, Riverbend established a new standard that integrated rather than separated its residents from their urban context, thereby eliminating the ghettoization of public housing that earlier urban renewal had imposed.

The future of the firm was by no means clear, but by that time the young partners had felt enough success to branch out in their personal and professional lives. They took on teaching positions at various architecture programs, including Cooper Union, Harvard, and Yale, both to supplement income and keep up with colleagues and design trends. They also carried on in their personal lives, married, began families, and in short order started thinking about designing their own houses as a way to explore their many personal ideas about architecture.

Wisniewski discovered Martha’s Vineyard through fellow architect Richard Brigham, who had built a small modern house in Menemsha in the late 1950s. Brigham, another Harvard GSD graduate, knew Cape Cod for its summer enclave of European modernists, including GSD leaders Gropius and Breuer. But while the Cape became the summer residence for the old school, the affordability and remoteness of the Vineyard attracted the next generation of modernists.

Wisniewski instantly fell in love with the Island. He bought more than seven acres of land in Chilmark with financial backing from his sister, Dr. Harriet Wisniewski, a successful New York radiologist and his faithful architectural patron. Aware that the well-known designer Eliot Noyes had a home near his site, and with visions of a new summer architectural enclave, he divided his parcel into three lots, selling one to Brody, and the other to Richard Stein, another GSD grad and New York–based architect who was friends with both Brody and Noyes. In short order all three were designing their respective getaways.

Wisniewski’s Glass House was, from the onset, a never-ending laboratory of design where he could take his preferred approach to experimenting with problems and seeking out new technological solutions. He came up with the overall idea for the design in just one night and engineered the home to be prefabricated, with parts made by a carpenter near his New York office and transported for easy assembly by relatively unskilled laborers. With help from his two brothers, Ray, also an architect, and Ed, plus a few Vineyarders, he assembled the original structure, consisting of thirty-eight support columns and roof panels, in less than two days. It took several subsequent trips to install the large glass panels, the flooring, decking, the various infrastructures, and to finish the interior.

By September 1962, when Wisniewski took his future wife, Lois, on their aforementioned date to the Island, the house was nearly complete. One year earlier it had garnered Progressive

Architecture’s design citation, when it was still basically an enclosed shell with only the most basic electricity and plumbing but still without modern conveniences like a washing machine or radio. Lois, an administrative assistant in the New York architecture and planning firm Oppenheimer, Brady, and Lehrecke, found the place exhilarating. In spite of its highbrow design, they both considered the experience of the house to be a kind of glorified camping and took pride in using its most rustic amenities such as oil lamps and its exposed open courtyard shower. Wisniewski also designed a second building for the site that was supposed to hide plumbing units and create storage. He finally got around to assembling it in 1965, two years after he and Lois had married and had children.

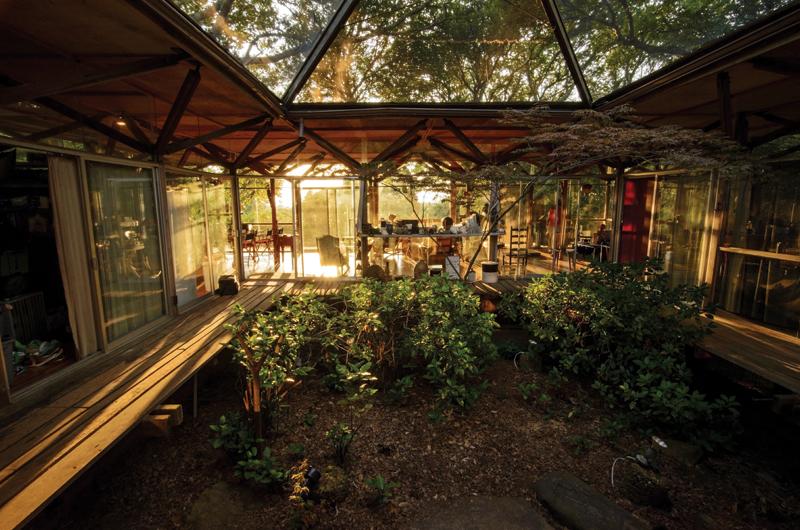

Although the Glass House is transparent from all vistas, it provides space for private activity as is required by family life. The overall building plan is a squared-off donut, with the hole becoming an open courtyard covered by a filmy screen to keep out animals and insects. The house has two sliding screen doors opening to the outside, one allowing entry to the house and one leading to a raised wooden deck that extends the inside rooms and wraps around the entire house. The circulation to the interior rooms is provided by a narrow deck on the inside of the donut that opens onto each room.

Set on a platform over the natural woodland, the home’s inset walls of glass are supported by thirty-eight slender wooden umbrella-shaped columns. The resulting uniformity and lightness of the structure, combined with the transparency of the glass, fulfilled Wisniewski’s aesthetic goal of dematerializing the building as much as possible, thereby fusing the house as shelter with the experience of living in the surrounding woods. The effect is transparency during the day and by night: when the interiors are softly illuminated, the splaying columns appear as though the forest’s trees have moved inside.

“It was one of those places where people just felt free,” is how Lois described it. “We could move around and see people moving through the space through the glass – quite beautiful. It was like living outside, only we were on the inside.”

With no walls or partitions in the interiors, privacy happens through a system of floor-to-ceiling curtains that can be pulled to separate rooms as needed or provide privacy from the outside. Adding to the sense of collective creativity and family togetherness, Lois and Harriet Wisniewski had the daunting task of hand-sewing the yards and yards of fabric and inserting thousands of grommets required to fabricate the intricate interior curtain system.

With its raw materials, exposed structures, and furnishings gathered from Island consignment shops, the Glass House defies pretense. Although intended for summer use, Wisniewski’s first design included a formidable stone fireplace. Finding that the weight of the stone grounded his otherwise light aesthetic, he decided against it and installed a wood-burning stove to stave off occasional cool weather.

The home thrilled and challenged the Wisniewski family, for it lived up to its “experimental” moniker and required unending maintenance. For the most part, the family accepted the mandate because they understood that this was the building’s raison d’être. Over the years Wisniewski constantly upgraded materials, rethought details, and taught his children how to fix inevitable leaks among a myriad of problems. Lois recalled a time in the early years when the walls of glass chipped, splintered, and flew around the house during a torrential storm. She had to run to the car for cover, small children in tow. Over time, however, the house worked better and better.

“Of course it was a lot of work,” said Lois. “One or two people cleaning the windows on a glass house, inside and out. Very intensive labor.

“The house was not always easy,” she summed up, “but…it was always exceptional.”

While less transparent than its neighboring Glass House, the house that Brody built next door in 1962 just as clearly revealed the architecture he was exploring at the time. With this project Brody studied the idea of a house as a container for living: architecture that was flexible enough to enable the activities of typical family life without restricting activities yet undetermined. Designing the house, his son David recalled, was for his father “about creating an aesthetic environment as well as a functional environment.

“The house,” he went on, “gives you a certain kind of pleasure being able to perform in it. Good architecture is a collaboration with the people who use it.”

Considering the variety of ways in which people would actually use his buildings remained paramount in all of Brody’s work, whether in the massive urban projects the firm in New York was increasingly producing or in his own summer retreat. The design for the Vineyard house therefore disposed of any notion of traditional rooms with their inherent preconceived restrictions. Rather, Brody designed the house to be the most essential shelter required in the context of Chilmark: an empty volume that allowed his family to continually redefine it. “The principle requirement was that it have a large, open space where three children – and parents as well – could explode after a winter in cramped city quarters,” he told Progressive Architecture in 1963.

“Sam really didn’t care about showiness, or possessions for that matter,” said his wife, fine artist Sally Brody. “He just wanted to create a good environment for his family to enjoy. A place that was inexpensive, functional, and in all ways beautiful, where architecture would just speak for itself.”

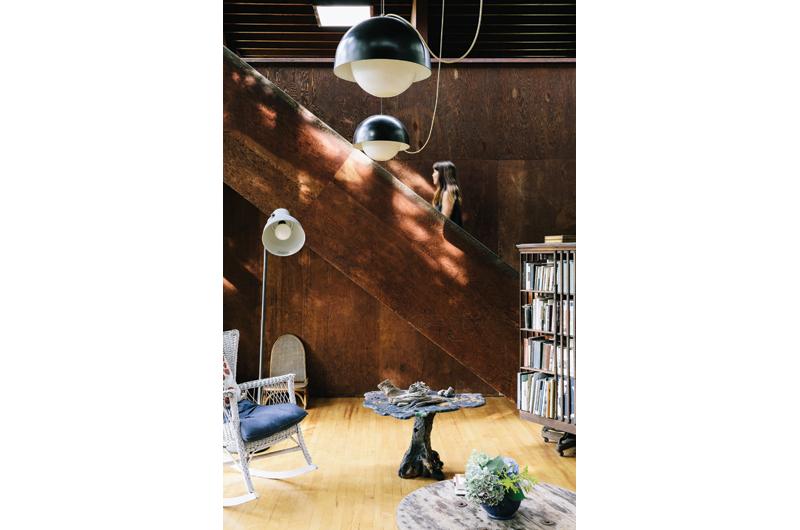

The house is a clean two-story rectilinear Miesian box. The central portion of the interior volume opens up through both stories with the ends of the box broken into two floors that provide secluded alcoves to house the kitchen, bedrooms, and baths. Like the Glass House, there is ample transparency across the open plan, in this case with half walls and lofts that open onto each other. The one exception to the open plan is the downstairs guest quarters, the only room that has a working door. The house eliminates the front door, allowing flow from one side to the other through large sliding glass panels.

The defining feature of the house is its floor-to-roofline jalousie windows that, along with large transverse skylights, allow the sun to flood the rooms while still catching available winds to control indoor temperatures. A perforated bridge connects the second story lofts over the main entry and provides the best view from the house to distant Menemsha Pond.

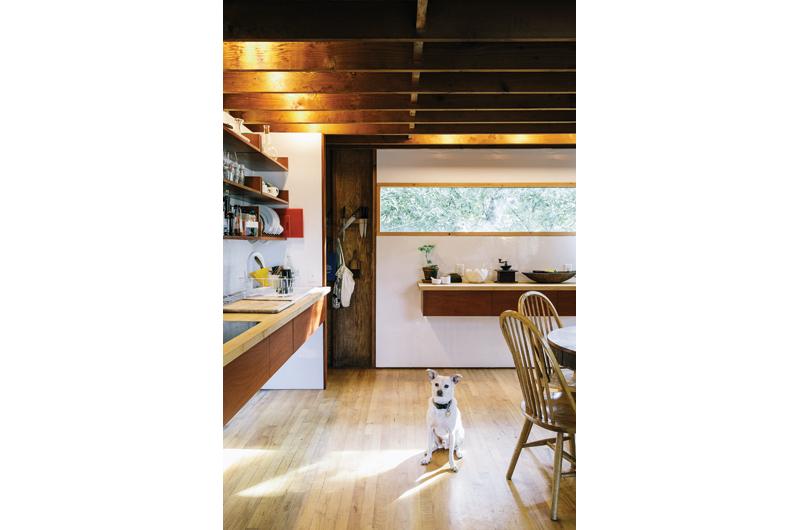

Like the Glass House, the Brody house eschews posturing – not only in its extensive design simplicity but in how it was actually built and its respect for vernacular buildings in Chilmark. Determined to use Vineyard builders and craftsmen exclusively and to be cost effective, Brody designed the house to use conventional post-and-beam construction with materials readily available on the Island. The exterior cedar shingles are a reference to the shingled cottages that define the Vineyard’s architectural identity.

The entire house, with furnishings and site work, cost $14,000, a budget so tight that the interiors were left unfinished with surfaces of exposed plywood, double milled to reduce splintering. But in the spirit of easy summer living, Brody decided that his unfussy interiors suited his original design intent: to promote freedom of use. As he happily described it in a 1965 Progressive Architecture article: “If you feel like driving a nail in the wall to hang a picture, kite, or fish, there is nothing, nothing at all to inhibit you.”

In the 1960s and ’70s the lives of the Brody and Wisniewski families were enriched by their connection to the informal architecture community in their corner of Chilmark. The Wisniewski family often came up in May after Chet finished teaching and stayed as long as they could through July when they often gave up their house for August income rental. Lois recalled her long friendships with the Steins, Brighams, and Brodys, defined by cocktail parties and dinners, sleepovers among the kids, and shared gardening with her fellow wives. Sally Brody recalled the weekdays when she, like many women, facilitated the children’s activities while their husbands were off-Island working, in her case trying to fit in time to pursue her own career as a painter.

The children from both families described their Vineyard experiences as unfettered, free, and delightfully isolated – not from each other but from the responsibilities of the off-Island world. Careening without helmets on bikes down to Menemsha, rainy-day art projects, and annual sandcastle competitions on Lucy Vincent Beach provided years of summer memories. For the most part they remembered their modern houses not so much as buildings that they would retreat into, but rather as places they could pass through on their way to explore the Island.

In the mid-’60s DBW began its inevitable transformation, building on the success of Riverbend and going on to great acclaim in low-income housing in New York. All the while the owners were assembling one of the most socially progressive firms in the city, hiring not only men but talented female architects and architects of color, a practice that was extraordinary in this era.

Wisniewski, who had become less interested in DBW’s urban planning work, left the partnership in the mid-’60s while he was designing Temple Beth Shalom in Livingston, New Jersey, a modern synagogue with an unprecedented stained glass sanctuary crafted by sculptor Samuel Wiener. Although the temple was a critical success, Wisniewski found the overall experience of

designing it on his own unsatisfying. He went on to do a number of interesting projects in private practice, but for the most part focused on teaching full time at Cooper Union, spending more time on the Island to care for the Glass House, painting, and continuing to explore his architecture.

Although their professional paths took them in different directions, Wisniewski and Brody remained close friends, a relationship strengthened by a mutual respect for one another’s architectural achievements. Nowhere was this more evident than in a 2005 video interview of Wisniewski, then eighty-three, taken by Brody’s son David, himself an artist and writer and now primary steward of the family’s Island house. Talking about the design history of the Glass House, Wisniewski made a point of reflecting on the different sort of beauty Brody achieved next door, as well as the impact Brody had on housing in the city.

Though not as famous as their forefathers Wright and Le Corbusier, Wisniewski and Brody were among the last of the true modernists: practical at every turn, eschewing self-aggrandizement, concerned only with producing beautiful, socially responsible work. As Brody noted in a 1988 Architectural Record article: “We [Davis & Brody] have been rather eclipsed as architectural figures – partly because we aren’t interested in creating signature buildings in housing. [M]ost of the buildings today have nothing to do with the continuity of the city’s fabric – in fact they destroy it. I think architects must develop a sense of personal security about who they are and what they are really trying to do, remembering that they (the buildings, not the architects) are likely to be around for 50–100 years.”

In 1992, just a few years after that interview, Brody died at the age of sixty-five. Wisniewski continued to come to the Island, eventually living there full time until he died in 2015 at the age of ninety-three. Their Chilmark homes are still thoughtfully maintained and enjoyed by their children and grandchildren, who use the houses much in the same way and spirit in which they were conceived. The families have made minor upgrades to the houses, including sensitive kitchen remodels, both clearly deferential to their original designs.

The houses remain in great form after fifty-plus years, serving not only as unique reminders of the idealism that was the theoretical underpinning of modernism in the postwar years, but of the exceptional friendship between the architects, wives, and families that built them.

For part one of our exploration of the mid-century modern heritage on the Vineyard, read Beth Edwards Harris's piece on Eliot Noyes: From Bauhaus to...Chilmark?

4 comments

4 comments

Comments (4)