It had been a long, dry winter for the dinosaurs of Massachusetts. The forest was parched and pools of standing water – draped in greenery and hosting plant-eating giants – had long since dried up. The river ran low. But the arid season was over, and the distant rumble of thunder announced the New England monsoon. The air swirled, the sky filled with shadows, and the throbbing midday drone of insects hushed as the gloom approached.

One tree had stood there for decades under the ancient sun, indifferent to the menace of passing carnosaurs, when a blinding flash suddenly splintered the conifer and, in Cretaceous air drenched with oxygen, the thunderstruck forest exploded in flames. The killers scattered for shelter. The sagging charcoal clouds suddenly gave up their ballast, adding torrents that did little to dampen the blaze. The rain carried the fallen tree – smoldering and blackened – into a river now roaring with storm water that poured off the distant Appalachian highlands. Dinosaurs crossing the floods fought panic as fire towered over the riverbanks. A baby duckbill washed away. The muddy, meandering river – on its way to the plesiosaur-haunted Atlantic – surged over its banks, and a thicket of branches and logs washed over the levee, coming to rest in a backswamp. The wood was quickly covered with silt. It kept raining and raining.

The storm subsided. An eternity passed. The hunk of the tree emerged from the clay to a brush of salty air, and the warmth of a sun it hadn’t felt in eighty-eight million years. The old wood tumbled to the bottom of a cliff at the edge of the sea. I took out my iPhone and took a picture of it.

“People walking on the beach don’t realize what it is,” says Indiana University Southeast paleobotanist David Winship Taylor, Ph.D., about the ancient charcoal – chunks of which spill from the dark lignite layers of Aquinnah and Chilmark. “They think, ‘Oh, there’s a piece of charcoal, throw it on the grill!’ But you know, that’s ninety-million-year-old charcoal! You’re burning fossils.”

Fossils forged in the supercharged forest fires of dinosaur times.

The Vineyard is typically thought to be the handiwork of ice age glaciers from around twenty thousand years ago, a relative eye blink in geological terms. And this is true: the Island was, in fact, bulldozed and sculpted by pulsing ice sheets at the edge of the tundra relatively recently. But the clays pushed up from under the earth by these glaciers – deposits that make up the Gay Head Cliffs of Aquinnah, that poke out in Chilmark, and that account for a good part of the western moraine of the Island – were originally laid down inconceivably deeper in time. Much of the deposits in the Gay Head Cliffs are from the height of the Mesozoic – the so-called Age of Reptiles. They’re part of a story five thousand times older than the rest of the Island.

All geologists have mental tricks for understanding (if only dimly) the abyss of deep geological time. The most illuminating one I’ve heard assumes that each footstep you take represents one hundred years. Now, starting in the present at – let’s say – the waterfront next to the Edgartown Yacht Club, and walking back across the parking lot toward Main Street, you would pass from AD into BC in twenty steps – or after only a few parking spaces. Sixty steps farther, or roughly at the other end of the parking lot, all of civilization would be behind you. By now woolly mammoths would still live on planet earth, clinging to remote island refuges. In the next few steps, mastodons and giant sloths would live on the dry land of Georges Bank, one hundred miles east of Cape Cod.

Picking up your pace, approaching Sundog and Edgartown Books, you would finally reach the height of the last ice age, more than twenty-thousand years ago. Most scientists agree there are no humans in North America (though there are camels and lions) and Boston is in perpetual darkness under the weight of almost a mile of ice – ice that a little farther south is reaching its maximum advance, pushing up old sediments and dumping out a ridge of rocks, boulders, and assorted till collected from points north that will eventually build up the necklace of islands from Staten Island to Nantucket.

So you’re now halfway up Main Street in Edgartown and the world is locked in ice and the bulk of Martha’s Vineyard is in the very act of its creation. But to get back to the age when the clays and sands of Gay Head were first laid down, in a Cretaceous river delta trammeled by dinosaurs, you’d have to walk not just a few dozen, or even a few hundred, more steps up Main Street. You’d have to keep walking across the entire Island to Vineyard Haven.

Then you’d have to get on a ferry to Woods Hole.

Then you’d have to walk to Washington, D.C.

Having done so, though now comfortably in dinosaur times, you would have covered only 5 percent of earth’s history.

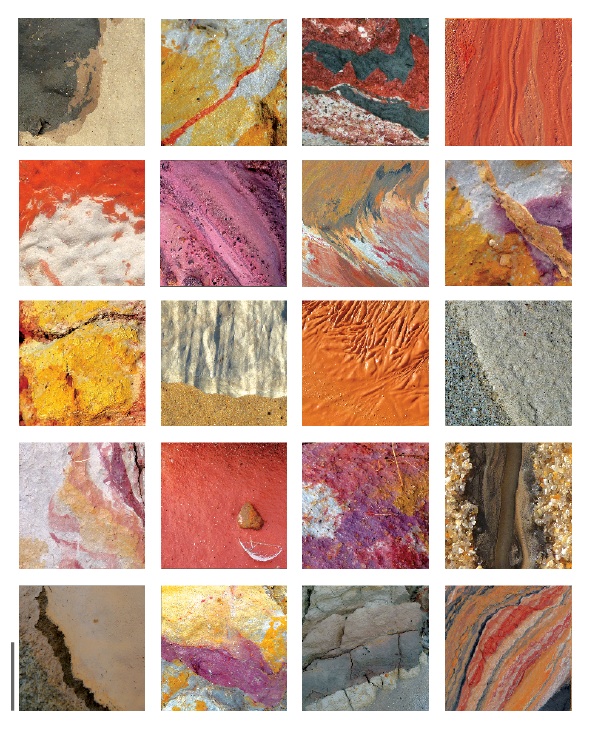

The Gay Head Cliffs, then, provide a window into the Mesozoic planet – a world far older than that shaped by the relatively recent advance and retreat of the ice. It’s a period of earth’s history that calls to mind the candy-striped canyons of the Southwest, or the banded badlands etched out of the Great Plains. On the leafy suburbanized East Coast, such exposures are rare, plowed over by strip malls and subdivisions, or concealed by woods and marshes. But here at the Cliffs, unique to eastern New England, the book is open, and the chapters of the ancient earth can be read.

Walking around the westernmost tip of the Island, the dazzling maroons and whites – and even ochre and lavender clays – in the Cliffs speak to a giant prehistoric river delta writhing

and emptying into what was then the young Atlantic Ocean somewhere nearby. In the shadow of the lighthouse, the huge faces of crumbling white sand are thought to be the point bars that formed by the accretion of sand along the inner edge of great bends in the ancient

river system.

Where these sands give way to clays – and the palette switches to darker, more brilliant iron and organic-rich reds – the ancient river spilled over its banks and settled out onto swampy floodplains patrolled by ferocious theropods. The candy-colored splendor of the clay speaks to the intense climate of the late Cretaceous. Today, red soils are only found near the tropics, but ninety million years ago carbon dioxide was much higher and it was 5 degrees Celsius warmer. Consequently, the ancient granite peaks of New Hampshire and Vermont were ceaselessly attacked by monsoons and subtropical heat – spilling their guts out onto the coastal plain. The Appalachian range, by then, was already in its senescence, a pale shade of its Himalaya-sized Paleozoic glory in the hundreds of millions of years before dinosaurs. Today, after at least two hundred and fifty million years of bad weather, their height has been ground down and spread sideways to the point that much of what remains of this once soaring mountain range is the vast, flat coastal plain that finally falls away at the edge

of the Atlantic continental shelf. As a geologist once told me, “The entire history of the earth is a competition between gravity and tectonics. And in the end gravity always wins.”

In places where this ancient coastal plain hasn’t been bulldozed up by monumental ice sheets, as it has been in Aquinnah (and under much of Chilmark), this older strata rests far beneath the surface. In 1976 the U.S. Geological Survey’s Raymond Hall drilled a borehole in Martha’s Vineyard’s state forest and hit the same layers exposed at Aquinnah, only four hundred to seven hundred feet underground. In the middle of these clays and sands Hall found an interruption of much darker coals – the same that swirl through the Gay Head Cliffs, where a poorly drained Cretaceous swamp was sealed up in the sediment and preserved for the ages. The scorched monkey puzzle trees that washed into these ancient swamps, like the charcoal found in late Cretaceous layers throughout the world, are what remains of fast-moving forest fires in the supercharged atmosphere.

“Oxygen levels were considerably higher than today, and we now know

for sure from the paleobotanical records that there were more forest fires,” says the paleobotanist Winship Taylor, who for as long as he can remember has been coming to a small camp on Chilmark Pond built in the 1920s. For him, the Cliffs and the ancient world entombed in them have offered an invitation to turn a childhood curiosity into a professional obsession.

“I’ve been going to the Gay Head Cliffs for almost sixty years,” he says. “We used to have a tradition of going down to the beach and grilling steaks for breakfast. In retrospect, the funny thing is that if you do go along there you’ll find this charcoal.”

It wasn’t until decades later, while pursuing a post-doctorate degree in paleobotany at Yale and studying the work of colleague Bruce Tiffney, that Winship Taylor realized that this same flash-fried debris in the Cliffs of his childhood provided a unique window into the early evolution of flowering plants. Remarkably, the same raging fires that turned this ancient forest to char also preserved even the most delicate flower parts. Today, Winship Taylor studies material from the Cliffs long stowed away in museum collections – including bits as fragile as eighty-eight-million-year-old petals, pistils, stamens, and seeds. The specimens are washed through sieves and painstakingly pulled apart with dissecting scopes.

“So this is a great project for grad students,” he says laughing. And lucky for him, the fruits and flowers of the Gay Head Cliffs are from one of the great transitional periods in the history of plants.

“This period in the Cretaceous is fascinating – it’s when flowers are going berserk,” he says. As paleontologist Loren Eiseley once wrote, “After a long period of hesitant evolutionary groping, [flowers] exploded upon the world with truly revolutionary violence.”

“By, say, one hundred and twenty million years ago we’re seeing a good diversity of them, but then they just go berserk in terms of species lineages and dominance of the environment into the late Cretaceous. So by ninety million years ago [the age of the Cliff deposits], we’re finding flowering plants basically coming out of the equator and going to each pole. We’re talking about, if you get a floristic sample, over half the species would be flowering plants. So it’s an age of rapid radiation.”

Polly Hill would be proud.

With the explosion of flowers came the co-evolution of strange new forms to pollinate and feed on them. Bees from these same layers have been found in New Jersey amber (think Jurassic Park). And though the awareness of rare moths on the Vineyard is a relatively recent development – the town of Chilmark has a “moth superintendent”– the oldest fossil moth egg ever found was pulled from the Cliffs. Not exactly a wash-ashore.

But the novel plants these insects evolved with were not quite like any found today. Winship Taylor and colleagues have described strange flowering plants from the Cliffs, seemingly related to oaks, but herblike and shrubby at best, growing in the shadows of the evergreens. There were no great stands of oak trees on earth, or of any other tree we’d recognize from today’s deciduous forests. Just as the world was dominated by dinosaurs and giant marine reptiles until catastrophe struck, in the forest it was dominated by conifers.

Though Winship Taylor, as an expert on ancient plants, was perhaps mildly annoyed that all my questions inevitably led back to dinosaurs, I couldn’t resist: were dinosaurs eating these strange new flowers and fruits at the Gay Head Cliffs?

“That’s really interesting, actually,” he says. “As you go from this period toward the [mass extinction twenty million years later], you see that two of the lineages are really diversifying. The duckbilled dinosaurs and the triceratops types – the ceratopsids. They’re actually radiating. And there’s one neat study that looked at triceratopsid coprolites – so, dung – and they pulled out this [flowering plant] biomarker. So I think we can pretty much say we know that some of these guys who were part of these radiating groups were eating these flowering plants.”

Unfortunately, the fossil record of dinosaurs in the eastern part of the country is notoriously spare. And at the Gay Head Cliffs, so far, it’s nonexistent. But that’s not because they weren’t here. It turns out that the same environments that are good for preserving flowers aren’t good for preserving giant skeletons – and vice versa. And there most certainly were dinosaurs in New England. In the early Jurassic, in Turner Falls, Massachusetts, and just outside of Hartford, Connecticut, large prowling theropods similar to dilophosaurs left their footsteps in lakeside flats, most famously at Dinosaur State Park in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, one of the largest dinosaur trackways in North America. But these footsteps were left more than one hundred million years earlier than the clays of Gay Head, a greater timespan than lies between ourselves and T. Rex. And after the early Jurassic – because of the quirks of tectonics – the rock record all but disappears in New England for eons. But, in fact, the dinosaurs do show up again – and in the very same layers as at the Gay Head Cliffs. You just have to go a little farther west.

Just as the Cretaceous layers of Aquinnah dive down under the rest of the Vineyard to the east (eventually thinning out somewhere deep under the Atlantic Ocean), so too do these dinosaur-age deposits dive down to the west, sneaking under the glacial dump heap of Long Island, only to poke out in rare outcrops, like one I visited at Caumsett State Park, an hour from New York City. There, where waves tear at the ragged bluffs of Great Gatsby’s Gold Coast, the same kind of red-daubed white sands of a Cretaceous river delta poke out from under the ice age till (just like on the Vineyard). And to the south, boreholes drilled on Fire Island have produced the same Gay Head strata as well, only remarkably thick. Even under Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a borehole struck this ninety-million-year-old clay, buried under glacial garbage and a top layer of insufferable coffee shops. But the mother lode for the red rocks etched on Aquinnah postcards – and held sacred by the Wampanoag for millennia – is in New Jersey.

In Chilmark, Vineyarders mined these dinosaur-age clays intermittently for more than two hundred years – a fossil chimney from a bustling brickmaking industry still rises from the bayberry and poison ivy below the Menemsha highlands. But just across Raritan Bay from Staten Island, in South Amboy, New Jersey, this same clay launched an entire clay-mining industry and built New York City. In fact, Aquinnah’s world-famous red clay is known to geologists as the South Amboy Fire Clay.

“These units were originally named by people mining the clay for brick,” says Rutgers geologist Kenneth Miller about the fire clay, which is part of a larger geological “unit” known as the Raritan formation. “We had three fabulous pits in Sayreville, New Jersey – the Sayre and Fisher pits. I’ve even got a brick on my desk that says S&F bricks.” But while on the Vineyard the exposed clay is protected, in New Jersey’s clay country, urban sprawl has swallowed the dinosaurs’ old haunts. “Eventually the exposures just got scuttled and turned into condos,” Miller says. “There’s very little left to take students out to.”

Now when he encounters the vivid reds of the South Amboy Fire Clay, it’s mostly in boreholes, through which he’s been able to map out big source rivers for the clays. One was “a sort of proto-Hudson to the north, and one through the central part of the state.

But there’s even a bigger source around Fire Island, so there had to be a paleo-Connecticut river that was huge. What the source is for Gay Head, though, I have no idea,” he says, laughing.

Martha’s Vineyard’s clays haven’t revealed any dinosaurs yet, but Rider University paleontologist William Gallagher, Ph.D., brought my attention to a site in northern New Jersey where the same layers have turned up the only Cretaceous dinosaur footprints east of the Mississippi. Ninety million years ago a menacing carnivore called Megalosauropus pressed its feet into the delta muck, leaving behind footsteps twenty inches long, spaced four feet apart. As for plant-eaters, though my opening sketch of a duckbilled dinosaur drowning in Massachusetts floods was speculative, one such Hadrosaurus is found slightly later in New Jersey and slightly earlier in Texas, and there’s no reason to suspect it wasn’t a part of the local ecology here as well.

There’s far more to the Gay Head Cliffs, and the Chilmark outcrops as well, than just a snapshot of life in the Mesozoic age of peaceful duckbilled dinosaurs and killer tyrannosaurs. A thin crumbling ribbon of green sand that cuts through the Cliffs is what’s known as – what else – “greensand.” It’s green from ancient fish crap that has been transmuted to glauconite by the ages, and it’s produced some of the more unusual fossil finds in New England.

The fragmentary nature of the rock record often produces huge jumps in time between layers, offering only tantalizing glimpses into deep time (the Grand Canyon famously sports a one-and-a-half-billion year intermission in its strata). Between the clays and the greensands of Aquinnah one such “unconformity” means that above the whites, reds, and blacks of the Cretaceous and their legendary inhabitants, we then rocket eighty million years forward in time to the greensands and the bottom of a shallow sea that invaded the coast during the Miocene Epoch, which lasted from about twenty-three million years ago to about five million years ago. And though the white shark in Jaws might have terrorized the Vineyard on film, it would have been positively bullied by its Miocene big brothers.

By ten million years ago T. Rex was long dead, but the sea now hosted an animal that perhaps rivaled it in sublime terror. This was Megalodon, a shark that once patrolled the continental shelf with almost unspeakable fearsomeness, topping sixty feet and feeding on whales. Sharks shed teeth like golden retrievers shed fur, and Megalodon shed its dental daggers all over the sea floor, from here to Maryland. When storms pummel the Island bluffs, these pearly talismans poke out of the greensands, still as sharply serrated as the day they dropped out of Megalodon’s man-sized maw. They dwarf the teeth of any known living shark. (It has to be stressed that digging for fossils in the Gay Head Cliffs or in Chilmark is strictly prohibited by both the Wampanoag Tribe and the town of Chilmark.)

But even without Megalodon these Miocene seas would have been filled with dread. Another shark represented in the Gay Head dental record is Otodus. Stretching well over thirty feet, this predator similarly would have dwarfed today’s pathetic great whites. Its teeth tumble out alongside those of giant rays, the vertebrae of primitive whales, and more familiar clams and crabs. Many of these fossils were described by the “father of geology” himself, British geologist Charles Lyell, who visited the Island in 1842 and, in his words, “collected many fossils here assisted by some resident Indians, who are very intelligent.”

Lyell’s condescension aside, thousands of years of stewardship of – and reverence for – the Cliffs have brought the Wampanoag more familiarity with the Island’s geology and paleontology than anyone. The clays, and the strange artifacts in them, are part of the Tribe’s very creation story of the Island by a benevolent giant, who lived on the Cliffs and wrestled with these prehistoric monsters.

“From near the entrance to his den on the Aquinnah Cliffs, Moshup would wade into the ocean, pick up a whale, fling it against the Cliffs to kill it, and then cook it over the fire that burned continually,” goes the Tribe’s official account of the legend of Moshup. “The blood from these whales stained the clay banks of the Cliffs dark red. The coals of the largest trees (which Moshup plucked up by the roots), the bones of the whales, shark’s teeth, and petrified quahogs that are still found today in the Cliffs are the refuse from Moshup’s table. The Aquinnah Cliffs are a sacred place to our tribe. They are imprinted with 100 million years of history.”

After the more familiar fossils of sharks, whales, and clams, the roster of greensand fossils begins to get very odd. Somehow, even in these offshore sediments, rhinoceros, mastodon, and camel bones mingle with the ancient marine life. These animals were likely carrion, washed out to sea from the mainland – what paleontologists call “bloat-and-floats.”

But the strangest fossils of all in these ten-million-year-old sands may be the polished pebbles of ancient coral, from hundreds of millions of years ago. They’re unlike any rocks in New England, but that’s because they’re not from New England. In fact, they might hail from as far away as the Hudson Bay in Canada. They were carried here in the stomachs of walruses and seals who used the rocks, called “gastroliths,” to aid digestion. The stones were collected by the creatures abroad and finally deposited when they reached the end of their world travels and died in Vineyard waters. The rocks are pieces of ancient coral reef – reefs that lived more than three hundred and sixty million years ago – but they’re found jumbled in the Cliffs with walrus ribs from only a few million years ago.

Such seeming contradictions in time aren’t that unusual in geology. When you’re dragging your boogie board down Long Point, you plunge your feet into sand that was delivered by glaciers within the last few thousand years. But if you dated this sand (specifically its zircons), it might report an age of six hundred million years old – older than animal life. This is the age of Dedham granite: volcanic rock from the dawn of life that the glaciers pulverized on their recent journey south and delivered to the Island as sand.

Above the greensands we finally drop into the three-million-year-old ice age. When this glacial age began it killed the Megalodon. And when it ended...well, the ice age never really ended. As far as we know it’s only temporarily retreated to Greenland and Antarctica. There have been dozens of brief, warm interglacial intermissions set within this giant ice age, like the one that began twelve thousand years ago and that continues to the present day. These warm vacations are initiated by earth’s periodic wobble into the sunlight, and if humans weren’t currently injecting gigatons of heat-trapping gas into the atmosphere each year, we might soon be headed back into the larger ice age that created Martha’s Vineyard. Instead, we’re on pace for a reprise of the late Cretaceous greenhouse of Megalosauropus, with resulting sea-level rises due to continued melting of polar ice that conceivably threaten the very existence of the Island as we know it.

Wherever it ends, the ongoing glacial story of the Vineyard begins after the greensands, in the thin layer of sands and boulders that caps the Cliffs and makes up the Island’s morainal spines. It’s a story that is not settled science, but that mostly took place in the last twenty thousand years and spans, at most, one hundred and thirty-five thousand years or so. It’s just a walk, in other words, across town.

This is the strangest thing about geology. Though it’s been a truism since Heraclitus that everything changes, geology takes this insight to an extreme. Eventually in the geological future – a future that will come as surely as the next sunrise – all of this will be gone. Wherever you stake your claim, your plot of earth might have once been the site of snowcapped Himalayas or dinosaur-trampled jungles. And in a distant future it might be a shifting sand sea, or the bottom of the ocean.

For now, though – around here – it’s a beautiful Island. With staggeringly beautiful cliffs.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)