The “Dude Train,” the “Flying Dude,” the “Dude Flyer.” It’s one of the most famous passenger trains ever to run in New England, but you couldn’t walk up and buy a ticket to board it. Nor did any of its various nicknames ever appear in an official timetable or on a station wall. Yet for thirty-three summers, from 1884 to 1916, it plied the tracks from Boston to Woods Hole, a distance of seventy-two miles, whisking wealthy Bostonians at unprecedented speeds and with unsurpassed luxury from their city offices to their summer retreats on Cape Cod and the Islands. It was a sort of NetJets for the Gilded Age, a unique, subscription-only private train. And though it last ran a century ago, and the tracks down to the ferry landing have long since been converted into a bike path, for train aficionados, the Dude abides.

It began in early 1884, when a group of well-heeled and patrician Bostonians with homes or connections on Buzzards Bay, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket approached the Old Colony Railroad with a proposition. Known as the “Train Club” or sometimes just “the Club,” they were a virtual Boston who’s who. There was the banker John Parkinson; the Forbes family, who owned Naushon and most of the rest of the Elizabeth Islands and who also frequented the Vineyard; W. E. C. Eustis, known as the “Copper King,” whose cousin George Dexter Eustis had an estate called Hollyholm near Cape Higgon in Chilmark; Brigadier General Charles Paine, who served throughout the Civil War and was a renowned yachtsman; cousins Robert and Alfred Winsor, each of whom owned an island near Hospital Cove in Bourne; and Richard Olney, President Grover Cleveland’s secretary of state. President Cleveland himself, who reportedly fished at Squibnocket in 1897, was also a regular on the train. Other illustrious names on the roster included Minot, Emmons, Fay, Weld, Wilson, Ditmar, and Beebe. (Years later, Lucius Beebe, a scion of that clan and a prolific author, covered the Dude Train in The Trains We Rode, a book he wrote with Charles Clegg in 1965.)

What they wanted, the club’s executive committee explained to the railroad, was a seasonal, private, posh, weekday train that would allow them relatively full days in their Boston offices with plenty of time for a leisurely business lunch, yet get them to their summer homes in ample time for cocktails with their families. In exchange, they would guarantee the railroad a minimum income for the season: by 1914, for example, the figure was $22,185 for a season lasting from June 5 to October 5.

To raise the money, members and their families were assessed $100 per person – about $2,500 in today’s currency – on top of which they would pay the regular rail fare each time they traveled. There was no extra charge for packages, suitcases, and trunks weighing sixty pounds or less, and guests could ride by presenting a card signed by a member. If a conductor ascertained that the rider wasn’t actually headed for the member’s house, however, that “guest” might be unceremoniously put off the train. Interestingly, these details survive thanks to an investigation by the public utilities commission into charges of discrimination, which concluded that “the arrangements for the summer are in conformity to law and the train will be allowed to run.”

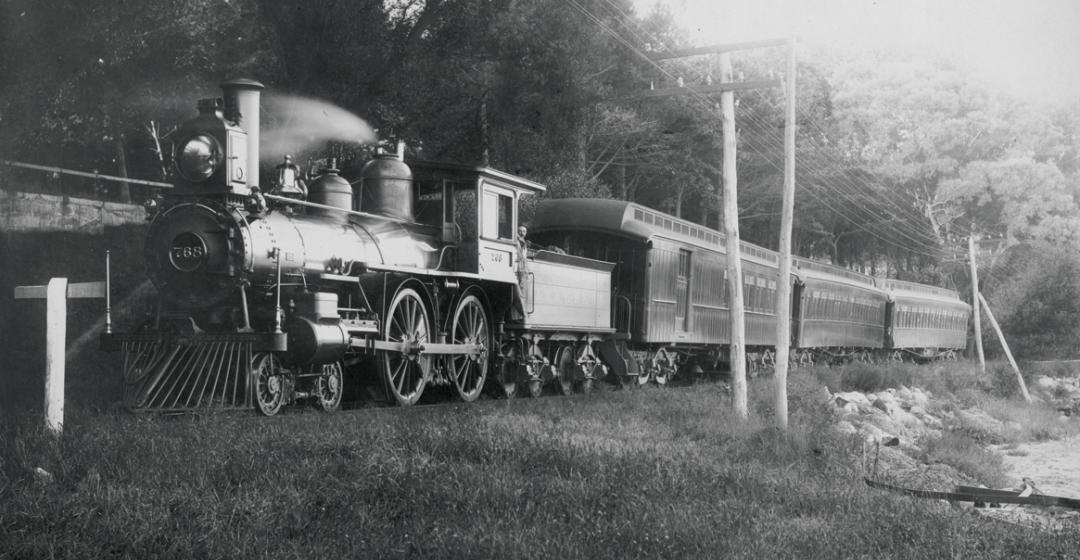

The train made its first run on June 23, 1884. Its original make-up – railroaders would call it the “consist” – was a combination baggage-smoking car and two drawing-room cars, named Naushon (the Forbes’ island) and Mayflower. Additional drawing-room cars that came later were Cottage City (as Oak Bluffs was known at the time) and King Philip (presumably after the Wampanoag resistance leader of 1675, whose real name was Metacomet). These cars, of wooden construction, were elegant: highly polished wood interiors tricked out in brass, with plush seats. Perhaps surprisingly, the original locomotive, No. 100, or “Foxboro” – locomotives were often named in that era – was something of a veteran, having been built by the Rhode Island Locomotive works in 1870 for the Boston, Clinton & Fitchburg Railroad. (That line was later absorbed by the Old Colony Railroad, which in turn was absorbed by the New York, New Haven, & Hartford Railroad.) It had a tall smokestack, oil headlight, and stubby tender coupled behind, adequate to carry the coal and water needed for the Dude’s short run.

On its original schedule, which changed little over the years, the Dude left Woods Hole at 7:40 a.m. and arrived at Boston’s Kneeland Street Station at 9:25 a.m. (When Boston’s South Station opened in 1899, that became the Dude’s terminal.) The train departed Boston at 3:10 p.m. for a 4:50 p.m. arrival at Woods Hole. In 1892 a second Dude was born, to serve Marion, Mattapoisett, and Fairhaven on the Fairhaven Branch, and after 1896 the two Dudes ran as one train north of Tremont, then split into trains for Fairhaven and Woods Hole.

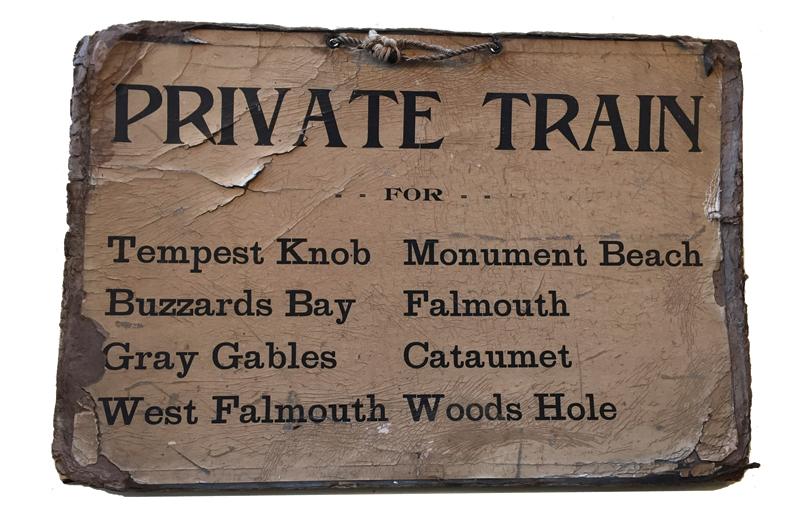

According to the “Private Train” sign that hung in Kneeland Street Station, the Dude served Tempest Knob in Wareham, Buzzards Bay, Gray Gables, West Falmouth, Monument Beach, Falmouth, and Cataumet en route to Woods Hole. Perhaps most interesting of all stops was the dollhouse-like depot at Gray Gables, built for President Cleveland during the time between his two terms. Gray Gables, on Monument Neck in Bourne, was the Summer White House during his second term, from 1893 to 1896. The little depot the president used is now preserved at the nearby Aptucxet Trading Post Museum, operated by the Bourne Historical Society.

What club members got for their money in addition to exclusivity and deluxe accommodations was speed. At roughly an hour and forty-five minutes each way, the Dude saved over an hour compared to the regular trains between Boston and Woods Hole. This was accomplished by running express as far as Tempest Knob and after that stopping only “on demand,” where a member or guest wished to board or disembark. Though average speed over the entire run was 43 miles per hour, between Brockton and Middleboro the Dude would touch 60 miles per hour – “flying,” indeed, for that early era of railroading.

Another important perquisite of membership was the privilege of shipping goods. Mrs. Alfred Winsor reportedly sent weekly postcards to Fitch Brothers grocers in Boston ordering all her provisions with the instruction “Send down on the Dude.” Mrs. Charles S. Hamlin was another regular on the train. “Every shop in Boston,” she recorded in her journal, “had large labels marked, usually in large red printing, ‘Dude, South Station.’”

Exactly who started calling it the Dude Train is not known for certain. Employees’ timetables listed the train only as “Limited Express Passenger” and public timetables never mentioned it at all. The nickname is thought to be a coinage of Harry Meyers, its first conductor, who likely picked it up from the passengers. At that time “dude” did not mean an urbanite at a recreational Western ranch, a wannabe surfer, or a middle-aged bowler in a cardigan. Nor was it a general term of address. It meant a dandy, a fashionable man perhaps excessively concerned with clothes and manners.

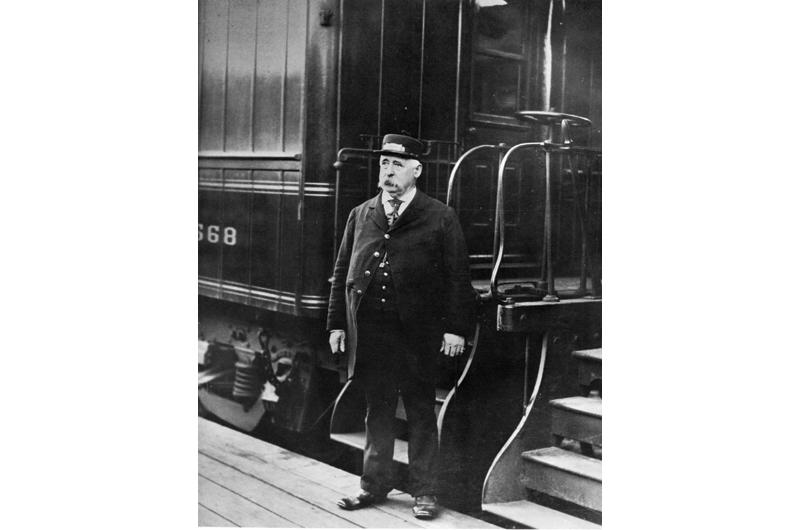

Meyers may have named the train, but Augustus S. Messer, who took over as conductor in 1889, is the man most closely identified with it. A lifelong railroad man and a conductor on the Woods Hole Branch for thirty-two years – fourteen of them on the Dude – he was an imposing man, with a walrus mustache and a prodigious girth that allowed only the top brass button of his dark-blue uniform jacket to be closed. It was universal railroad practice that the conductor, not the engineer, as one might expect, was in charge of the train, and Messer looked more than able to fill that role. He personified the train to his regular riders, with whom he mixed comfortably in spite of their exalted and moneyed status. He even took President Cleveland, on his way to Gray Gables, in stride.

Presidents were one thing: new Pullman cars were apparently something else. In 1904 the New Haven, which had taken over the line from the Old Colony, acquired $77,800 worth of new Pullmans – three parlor cars and two baggage-smokers – for the Dude. On May 19 they appeared at a South Station platform to begin the train’s twentieth season and Messer’s fifteenth at the helm. But after that season-inaugural run to Woods Hole, Messer suffered a stroke and died. “It ranks as the finest train in New England,” the Falmouth Enterprise wrote of the Dude in reporting on Messer’s death. “Its first run was celebrated as a noteworthy event...and it is thought that the excitement...brought on Conductor Messer’s fatal illness. During the evening when he was at work on his first reports he was stricken with a shock from which he never recovered.”

The Dude rolled through its final thirteen seasons without its impresario, and was a moneymaker to the end. But with the United States’ entry into World War I imminent, and ever more travelers driving automobiles, the end was clearly approaching for the Dude as it soldiered through the summer season of 1916. That end came on October 2, catching some of its loyal riders by surprise. “When we left Mattapoisett the fall of 1916,” Mrs. Hamlin wrote in her journal, “we did not realize we were saying good-bye to the Dude train. We would have wondered how we could live there without the Dude....”

How the Other Half Chugged

On July 18, 1872, twelve years before the first Dude Train, the eighteen-mile Woods Hole Branch opened to the public and delivered passengers to the waiting sidewheel paddle steamer Island Home. Financed in part by bonds to which such prominent Vineyarders as Dr. Daniel Fisher and the management of the Oak Bluffs Land & Wharf Company subscribed, construction had begun at Cohasset Narrows, now called Buzzards Bay, and immediately crossed the Monument River on a 320-foot-long trestle. The river was later converted into the Cape Cod Canal, which was completed in 1916, and the rails now cross the magnificent 1935 vertical lift bridge, visible from the Bourne Bridge. As investors had hoped, completion of the line caused land values along Buzzards Bay and on the Islands to boom.

Many trains other than the Dude plied the branch, of course, including through trains from New York, such as the Day and Night Cape Codders and Neptune, and multiple trains to Boston, including some expresses. As happened nationwide, however, train service diminished through the 1950s. Years of threats of total abandonment of the branch escalated in 1959, when the Vineyard Gazette editorialized, “The importance to this island of Boston to Woods Hole and New York to Woods Hole trains in the summer season can hardly be overemphasized.”

But New Haven finally had its way and passenger service on the Woods Hole Branch ended in 1964. The rails of the three-and-a-half-mile Falmouth–Woods Hole stretch were lifted in 1969, and that right of way is today the Shining Sea Bikeway. In the last years, the Woods Hole trains were self-propelled rail diesel cars, called RDCs, or “Budd Cars,” since they were built by the Budd Company. These utilitarian coaches were about as far from the Dude Train as a rider could get – but at least they were open to anyone who had the fare.

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)