Some works of art are an invitation to participate; others, like Frances McGuire’s oil paintings on canvas, are an invitation to reflect. “I’m a documentarian,” said McGuire, “but, let me clarify: I’m not a realist, or a purist. I fictionalize what I see and feel based on the intensity of my emotional connection to a site.” And for decades – with a disquieting gap lasting many years between – she’s held steadfast focus on Oak Bluffs, or as this Jackson Heights, Queens-raised artist said, “The Vineyard, specifically Oak Bluffs, is my emotional home. I created my reality here, starting in the ninth grade, when I visited on an American Youth Hostel cycling trip.”

Other visits to the Island fed her spirit during her time as a student at the prestigious High School of Art and Design in Manhattan, and then Queens College, where she was taught largely by working artists responding to the grit and chaos of a 1970s-early 1980s New York City. “In the summer of my senior year of high school, my love affair with Oak Bluffs deepened,” recalled McGuire, her eyes scanning the room as if gazing through a window in time. “Earlier that spring, I wrote a letter to [Paul] Chase, the owner of the then Wesley House (now Summercamp hotel) asking for a summer job, and he said, ‘Yes!’” She smiled, “Actual letters. Handwritten.”

McGuire often starts sentences without completing them, letting the listener fill in the blanks, or not, which is why, after an anticipatory length of silence, she continued: “I fell into great loneliness as a student at Queens College, which was a commuter school. I longed for an away college experience, and working summers at the Wesley House became that experience for me. It was very, very formative.”

She spent the next five seasons working at the Wesley House, likening her coworkers and the Chases, its owners, to a family. But what crowds the foreground of her recollection is the physicality of the building and its sense of place. “I was extremely taken by being in that building with the wavy windows, and looking out to the harbor. You could see the ferry, the Tabernacle, and you could look up New York Avenue to Vineyard Haven,” McGuire detailed. “Every day was thrilling just to be in that hotel. I loved the spareness of the rooms; so unpretentious – fire buckets in the hallway – so simple, and exposed to the elements.”

McGuire’s speaking voice, like her painting voice, has a rich, tactile quality, and some words are spoken with such emphasis that it’s possible to believe you can touch them. “I sounded like this when I was a kid. I had to grow into my voice,” said McGuire, shaking her head. She’s comfortably forthcoming and moves through conversations in a non-linear fashion, like a time traveler, which she kind of is, often painting from photos she’s taken from as far back as the 1970s.

“I’ve always been an artist and an escapist. From a young age I would do anything to be outside,” McGuire said. “When I got older, every weekend I would ride my bike over the 59th Street Bridge and loop around and around Central Park.” Leaning in, she continued, “This is important, okay? I’ve always had a physical need to be outside, so I would create ways out in to the world.”

She inserts “okay?” not so much as a question but as a pause, allowing her words to catch up to her feelings, as well as an opportunity to pivot outwards, to confirm her listener is keeping apace and understands the import of what follows. Once affirmed, she rolls on, seamlessly, to her next point. In this moment: vibrant verbal snapshots of her adventures, most of which involved a bike, because after her parents’ divorce the family did not own a car. When McGuire wasn’t able to be outside, literally, she’d wish her way out – or in other worlds, “I’d pretend I was wandering the cornfields of Iowa, or I’d imagine winds from the Adirondacks making their way down from upstate, funneling between the buildings of the Manhattan skyline, and then into my open window.

“Can I just explain one thing?” interjected McGuire between thoughts. “I’ve always associated being a fine artist with self-centeredness. My father was an artist and an art teacher, and an alcoholic. I never considered a career in fine art, but after college, when I worked as the assistant director of the New York City’s Art Commission, I was constantly drawing in board meetings and painting by night, which brought me a lot of positive feedback from my colleagues,” McGuire said. “Working there was the equivalent to getting a Master’s. I mean, we had everyone coming in: I.M. Pei, Philip Johnson, Robert Ryman, Wolf Kahn. Every little aspect of a project was reviewed, whether it was signage, or a park design, or a new sculpture, or even the color of a bridge. Plus, we had great parties at City Hall...cops have great parties.”

McGuire’s oil paintings, ranging in size from 8 x 8 to 40 x 46 inches, share a strong horizontality. “I’m always fighting for a straight line,” McGuire confessed. “I will wrestle a painting to death.” One feels the invisible grid beneath the surface onto which she layers color and shape and light to create feeling. Each painting is a palimpsest of emotion – but not necessarily narrative – expressed without judgment or expectation. The visual equivalent of, “I’m just saying.” The formality, or construction, of her compositions and the more traditional use of materials loosen to shards of fractured light and color for punctuation. What McGuire paints is all there is; what was is unseen, but not hidden because there’s nothing to hide.

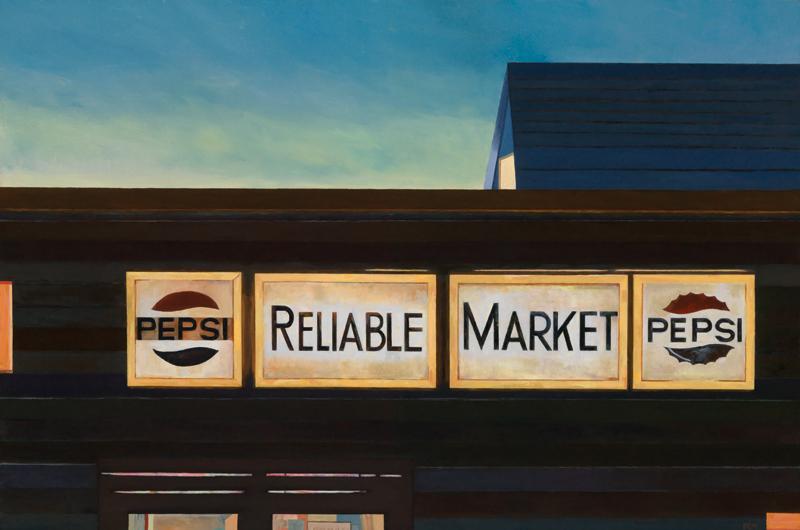

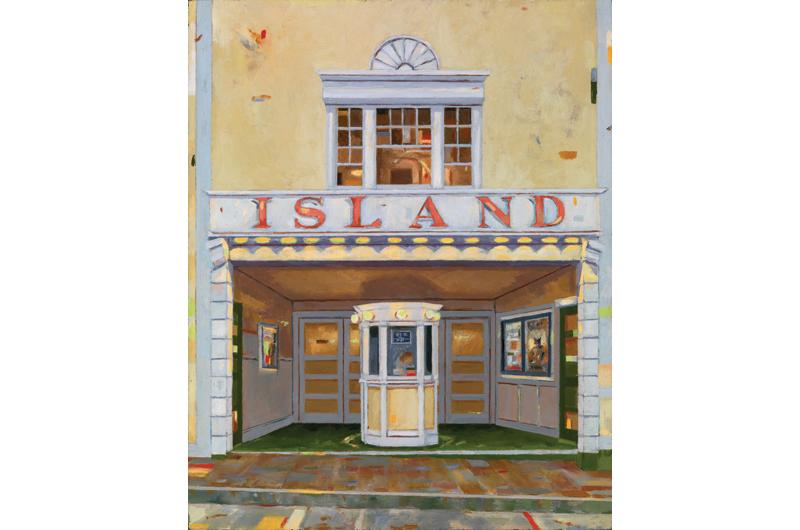

“I’m very into concrete Libby, alright?” asked McGuire, but it’s really a rhetorical question because her paintings are so transparently populated by the built materiality of a place – walls, buildings, and signage – or the space in between the brush and bramble of the natural landscape. In this way, one could even suggest that McGuire paints what she escapes to; that her preferred point of view is from the outside looking at, not in. But the feeling of her work speaks to a deep interior emotional landscape. “If there’s no emotional connection, I’m not interested,” she emphasized, without apology.

Fast forward many years, when McGuire – haunted by the ghost of an ended long-term relationship – was physically separated from the Island itself, but not from the intensity of her feelings for it. She married a man she described as a doer; “He’s a guy who gets things done. Without him, none of this is possible,” she said, gesturing wide. “I mean, he managed the cleanup of Ground Zero.” They had a son, now in college, and spent their summers hopscotching between the Jersey Shore, Cape Cod, and other destinations – everywhere but the Vineyard. All the while, McGuire was documenting, in photographs and paintings, what aesthetically moved her.

This backstory is necessary to fully appreciate the serendipity of her current story, and how the stars and beach stones aligned for McGuire to finally introduce her family to Oak Bluffs in the summer of 2009. That year they rented a cottage down the street from a house that three years later would become theirs, and that, coincidentally, neighbors the houses of the son and grandson of the beloved Mr. Chase from the Wesley House. Her return to Camelot coincided with the death of Senator Ted Kennedy. “We had left the Island and were driving back to New York when we saw the Department of Transportation’s digital signs acknowledging Kennedy for his service. That experience triggered profound feelings,” said McGuire. “Something happened on that ride home that reactivated my emotional connection to the Island, and I knew I had to paint. I was propelled to paint my seawall.”

McGuire’s surrender to long-held feelings, prompted by the roadside signs of Kennedy’s death, gave birth to what became a series of seawall paintings – based on photographs

she’d taken with her Pentax K1000 in the 1970s – that served to bridge her past and present tenures on the Island. Seawall paintings gave way to other views of Oak Bluffs: the concrete road posts along East Chop, the pipe railings along the beach, and, because of her affinity for signage integrated with architecture, she painted detailed portraits of the typographical-rich facades of Our Market, Reliable Market, and the landmark Island and Strand Theatres, among others.

This past winter and spring, McGuire has been working at a larger scale, for her, having just completed a mural for The Ritz in Oak Bluffs, as well as a private commission for Gretchen and Paul Massey. The latter, measuring 36 x 48 inches, is a painting of a room from their house on East Chop that was demolished to make way for their new home, in which this piece will hang. The room is spare, unpretentious, and masterfully depicted. Here, too, McGuire, as painter and documentarian, brought laser-focused execution and distillation of emotion to capture a finely articulated moment in history that allows the experiencer to experience the sense of place. In this way, art meets fact to become artifact.

8 comments

8 comments

Comments (8)