Prudy Burt swung her Toyota Tacoma off of North Road and onto the shoulder. She traipsed confidently through the brush, pushing branches out of her way as she headed for Mill Brook. A Burt-led tour of the brook is both history lesson and gossip column, environmental report and storytelling session. She names each pond and knows the property owner responsible for every dam (and whether their children like to fish). Burt catalogs every piece of information related to Mill Brook and it all comes back out in a rush: the place where a painter sets up her easel, the time Burt went to collect water temperatures and was attacked by swans, and where to look for the fish species that make this water their home.

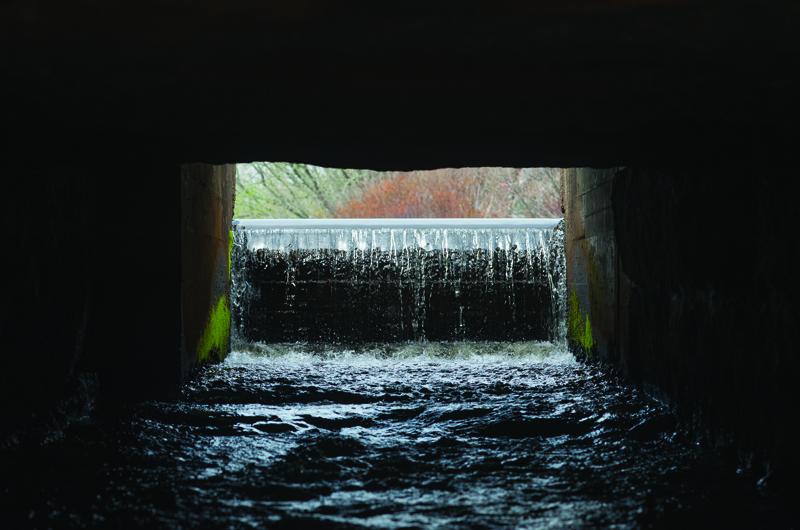

Mill Brook is a modest stream by off-Island standards. Roughly five miles long, it meanders along North Road and then State Road, periodically expanding behind small dams into a handful of manmade ponds along the way. Before the stream reaches Edgartown-West Tisbury Road it flows into the last pond, the Mill Pond.

This body of water covers what, for the past six years, has been the most controversial two and a half acres in West Tisbury. Some people, including a majority of the six-member Mill Pond Committee appointed by selectmen to study the issue, believe the pond is silting in and want the town to dredge it. On the other hand, Kent Healy, the town-appointed caretaker of the dam and member of the Mill Pond Committee, does not believe that the pond is getting shallower and argues that dredging is unnecessary.

And then there’s Burt, who believes the town should remove the dam at the foot of Mill Pond, allowing the pond to drain and the stream to flow freely. Her voice is often a lonely one: cajoling, debating, occasionally shouting, and insisting that removing the dam would benefit the ecology of the entire watershed.

Mill Pond rests next to the old West Tisbury police station. Passersby on the Edgartown-West Tisbury road might see swans floating serenely on the water. Or, in the spring, the Division of Fisheries and Wildlife stocking the pond with hatchery trout, followed promptly by anglers, most of them young. A more adventurous observer walking along the edge of the pond might see evidence of otters: pathways through the vegetation, piles of fish scales, scat mingling with tiny bones.

In Burt’s vision the dam is removed and Mill Brook is restored to its ancient free-flowing course to Tisbury Great Pond. In summer, the water temperature in the still Mill Pond can rise to a fish-stifling ninety degrees or more, but her imagined stream is filled with cold-water-loving wild sea-run brook trout. Anadromous ocean fish that spawn in fresh streams, such as smelt and river herring, would once again have unhindered access between the brook, the Great Pond, and the open ocean. Maybe the land where the pond once was would become a park, with grass for picnics and benches for watching the birds or glimpsing an otter in the flowing Mill Brook.

Burt isn’t tall or short, she’s not fat or thin, and her hair is neither brown nor gray. She wears round, wire-framed glasses that she adjusts by pushing her index finger against the bridge. When she has guests, the teakettle is scheduled to begin whistling when they walk in the door, and a plate of cookies is on the table. A sign in her kitchen reads “cursing and foul language is prohibited on these premises.”

“It all takes a shitload of energy,” she told me when I asked her to estimate the amount of time she’s given to her work with Mill Brook and the Mill Pond. It’s been at least fifty meetings between the board of selectmen and the Mill Pond Committee, five town meetings, three presentations to the community, and at least a dozen site visits with scientists; hundreds of hours in total. “It’s not like this is it, not like I’m blindly focused on it,” she said, protesting against invisible judgments. “But...it’s my thing.”

It’s not entirely clear what she means. Is it her passion? Her vocation? Her gift to her community? Mostly, though, you get the sense she sees this work as her gift to the stream itself. Recently, she read Running Silver: Restoring Atlantic Rivers and Their Great Fish Migrations by John Waldman, a book about removing dams. In it, there is a quote from the poet William Stafford that sticks with her and fuels her work: “Even the upper end of the river believes in the ocean.”

The current debate began nearly ten years ago, when some people in West Tisbury noticed an increase in weed growth around the perimeter of the pond and began to worry that it was slowly filling in with silt and sediment from upstream. The West Tisbury Conservation Commission contracted with an off-Island firm to conduct the first scientific study of the quality and depth of the water in Mill Pond, the nature of its wildlife, and the quantity and type of sediment. The resulting report, released in 2006, considered a variety of techniques for managing the pond, and recommended a more detailed watershed study be undertaken.

At that time Burt, whose family has been on the Island for generations and who grew up next to the Tiasquam River, was chair of the West Tisbury Conservation Commission. But she didn’t know anything about dam removal. “We used to get fliers and email alerts from what was then called Riverways,” she told me. Riverways, a state agency that’s now part of the Division of Ecological Restoration, works to restore and protect rivers, wetlands, and watersheds. “I read the words ‘dam removal’ on one of their email alerts and I was like, huh? You could take the dam out?” Burt said. “I grew up with all these mill ponds and that’s the way it was. It didn’t really occur to me that streams were running through the ponds [or to ask] how did these mills affect the streams?”

What the town of West Tisbury, its Mill Pond Committee, and Burt have are two interconnected questions. Do we dredge the pond or not? And, do we remove the dam or not? These questions aren’t just about pond-floor sediment, water levels, weed growth, water temperature, and fish passage; they’re about history, and who controls the symbol of a place.

For thousands of years what is today the humble Mill Brook was one of several mighty silt-filled rivers pouring off of the end of the last great continental glacier, carving out Tisbury Great Pond on its way to the then-distant sea. For thousands of years more, after the final retreat of the glaciers, it was a small woodland stream winding its way across the broad outwash plain. Then, within decades of the first European arrivals to the Island, the stream was put to work and became the heart of the new town.

The Story of the Old Mill is a small, fragile chapbook in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum library. Neither an author nor a publication date is listed. In it, the writer calls Mill Brook the Old Mill River, and describes it as the largest stream on the Island. Early in the era when European colonists came to the Island, the river was named Mill River and the Wampanoags called the West Tisbury area Takemmy – “the place where one goes to grind corn.” The book cites a deed dated August 11, 1760 as the first record of a grist mill on Mill Brook. There is reason to believe that the mill is actually much older, however. When Benjamin Church built the first grist mill on the nearby Tiasquam River in Chilmark in 1668, that stream became known as the New Mill River, which suggests to some historians that the “Old Mill” in West Tisbury must have been built before that date.

In the nineteenth century, both mills ceased grinding grain and were converted to small factories for carding wool and weaving satinet cloth. The mill at West Tisbury closed in the late 1800s, was eventually converted into a summer tearoom, and now houses the Martha’s Vineyard Garden Club.

More than a hundred years after the last industrial use of the dam and the Mill Pond, everyone agrees that there is a long history of human hands shaping Mill Brook and that it has served the town well. What they do not agree on is where to go from here. Bob Woodruff is the chairman of the Mill Pond Committee, which was appointed by the selectmen in 2008 and instructed to make recommendations about how to manage the Mill Pond. He is a strong and vocal supporter of dredging the pond and dredging it soon. By dredging the bottom of the pond, he and other advocates of this option argue, the town can undo whatever silting-in has taken place and can restore areas of cooler, fish-friendly water to the deeper portions of the pond.

“The Mill Pond Committee is totally in favor of a watershed study,” Woodruff said, referring to what has become a perennial debate in town about whether to wait for the results of a full scientific study of the river before taking steps to dredge the pond. But he doesn’t want to sit on his hands waiting for the results of a study when he believes the pond is filling in quickly. All of his fellow members of the Mill Pond Committee agree with him, except one.

The six-member Mill Pond Committee votes are often five to one, with Kent Healy as the dissenting voice. He’s a civil engineering consultant whose office is a workshop-like room off one end of his living room. The walls around him are stuffed with notebooks and binders that are filled with maps, records, and data of various types. He sits on a rolling office chair with his long legs bent at the knee, his heels kicked out behind him. A small drum kit takes up one corner of the workspace. One of the original members of the Mill Pond Committee, Healy believes that the available data doesn’t back up the notion that sediment is quickly rising in the pond.

“To dredge that pond will cost a half a million dollars and if you’re going to spend that amount of money you oughta be sure. That’s basically my point,” Healy told me. As he speaks, he smiles, shuffles papers, and waves his hands in front of his chest. As the town-appointed caretaker of the dam, he’s the one to conduct the engineer’s report when it is requested by the state, and he’s been measuring the water flow in the Tiasquam River and Mill Brook for twenty years.

“I’m not opposed to saving the pond; I’m not opposed to draining it either – but I do think most of the town would like to preserve the pond,” he said.

The issue came to a head at the spring town meeting this past April, when West Tisbury voters were again asked to approve funding both to complete the scientific study of the watershed and to develop a plan for the dredging of the pond. The money for the watershed study passed easily, but when the funding for dredging came up – well, let’s just say West Tisbury knows how to throw a good old-fashioned town meeting.

Woodruff and the others on the Mill Pond Committee who share his view stood on one side of the West Tisbury School gymnasium and tried to make the case that the pond needed “saving” and the only route was prompt dredging. On the other side of the gym, Healy, the lone dissenter on the committee, stood and argued that a few hot summers don’t make a dying pond. Between them sat a packed house of voters, more than a few of whom also stood to have their say one way or the other, eloquently and otherwise.

During the debate, very few speakers mentioned the notion of taking the dam down, though an obvious subtext of the pro-dredging “save the pond” contingent was the implication that choosing not to dredge would eventually doom the pond to being drained. Even Burt, who was one of the last to speak and excoriated the Mill Pond Committee for what she implied was sloppy preparation, did not make her case against dredging on the grounds that it would be ecologically wiser to restore the river. She said only that it was a waste of taxpayer money to plan a dredging operation before a decision to dredge had been made. When the vote came, 100 townspeople raised their hands in favor of dredging the pond while 119 voted against taking any action before the ecological study of the entire watershed is completed.

Burt is the first to say that the outcome, while gratifying, was not a vote in favor of restoring the river. “I think the vote had more to do with people not buying into all the emotional rhetoric that was going around than a real groundswell for dam removal,” she wrote in an email after the meeting. “But it’ll do for now. And, a big change from four years ago when only four of us raised our hands against dredging Mill Pond, and one of those was my mother.”

Even with the apparent gains, she knows she’s at a disadvantage in her quest. The pond is beloved and familiar, while removing the dam requires imagining a river that isn’t currently there. But West Tisbury would not be alone if it does chose to restore the Mill Brook – in Massachusetts in the past ten years thirty-three dams have been removed. This year, the second of four dams is being removed from Town Brook in Plymouth, a stream that has been in service even longer than the Mill Brook.

According to Beth Lambert, Aquatic Habitat Restoration Program Manager at the Department of Ecological Restoration, people’s fear of the unknown is the biggest challenge in every community. “They can’t envision what the site will look like,” she told me. But, she went on to say, “all dam removal projects have an ecological benefit. They restore habitat, improve water quality, and allow fish and wildlife to move through the river.”

According to Beth Lambert, Aquatic Habitat Restoration Program Manager at the Department of Ecological Restoration, people’s fear of the unknown is the biggest challenge in every community. “They can’t envision what the site will look like,” she told me. But, she went on to say, “all dam removal projects have an ecological benefit. They restore habitat, improve water quality, and allow fish and wildlife to move through the river.”

So Burt’s not going anywhere any time soon. She will keep moving, organizing presentations about the fishery, considering improvements along Mill Brook that contribute to fish passage. She’s measuring the water temperature at ten locations along the brook, and looking into the possibility of getting a landscape architect to draw a rendering of what a restored stream and surrounding land might look like. She looks at her mission as educational: “If I give you the information and you say, ‘I don’t care, I don’t care about eels or herring or trout or striped bass or any of the food chain,’ at least you know what you’re voting for.”

“I had this dream,” she said to me not long ago. She stood on Edgartown-West Tisbury Road, pond side of the guardrail and looked out over the water. She went on to say how often dreams are strange, surrealist interpretations of reality. “In most dreams this pond would drain and there would be a graveyard of cars down there, something like that.” But this dream was different.

Somehow, the town decided to see what would happen if they partially drained the pond by taking the boards out of the dam spillway, a suggestion that has been offered in real life. Burt said that in the dream, “It was pretty quiet, on an early spring day.” She was standing with Healy, overlooking the water much like she was when telling this story. “We were just chatting about this and that, watching the water level in the pond go down, quietly and slowly. We could hear birds singing, and as the pond emptied out, we could see the stream channel start to establish itself, the flow becoming more pronounced, with eddies and swirls beginning where the Mill Brook formerly was swallowed by the Mill Pond. I could hear the water as it started to bubble and flow. I could smell that great smell of flowing, fresh water.”

Even asleep, Burt believes that someday the headwaters of Mill Pond may make their uninterrupted journey to the ocean.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)