Drive up to the West Tisbury home of Phil Wallis and you are likely to be greeted by a super-friendly puppy that scrambles up your legs and dives into your car, his body trembling with excitement. It’s an energy and passion for life that the dog’s fifty-seven-year-old master seems to share. In his first few months as the new director of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, Wallis, the staff, and board of directors re-wrote the museum’s mission and vision statements, re-designed the logo as part of a “rebranding” effort, re-arranged the committee structure of the board, realigned staff titles and salaries, and raised close to $2 million. Most significant, perhaps, the board made the momentous decision to finally break ground on the first phase of the museum’s long-planned move from its Edgartown campus to the historic Marine Hospital in Vineyard Haven.

“Most organizations don’t go through all that in one hundred days,” Wallis enthused. “It tells me one thing: I was the right guy for the job!”

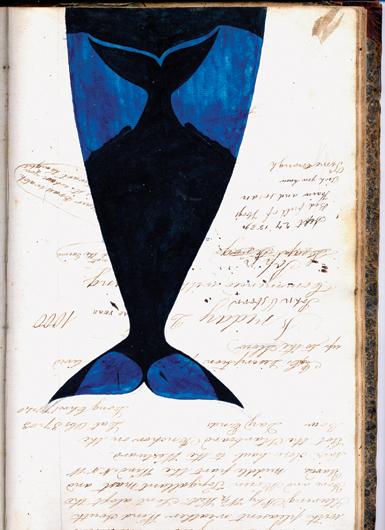

As stress-free as Wallis makes all this sound, the road to the Marine Hospital has come with its share of potholes, speed bumps, and previous reinventions. When first incorporated in 1923, the Dukes County Historical Society had an impressive collection of pre-revolutionary documents, but no home. The documents were stored instead in churches and private residences, until the Cooke House in Edgartown was purchased in 1932. As collections and membership in the society grew, the Edgartown campus slowly expanded to include a neighboring home, a research library, and several outbuildings to house various boats, farm implements, and other large artifacts – including the magnificent 1854 Fresnel lens, which for more than a century had been the beacon at the top of the Gay Head Light. After nearly a century of collecting, the museum has more than 30,000 items that relate to all aspects of life on Martha’s Vineyard, including fine art, furniture, photographs, textiles, manuscripts, and everyday objects made and used by Vineyarders from every community on the Island.

In 1996, the organization changed its name to the Martha’s Vineyard Historical Society, and then renamed and re-branded itself again in 2006 as the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Constant evolution is not uncommon for nonprofits, of course, but it’s fair to say that to both friends and the occasional critic, the museum has long appeared to be in a somewhat suspended state of rebranding and self-discovery with little to show for it other than new logos. With great fanfare in 2002, the museum bought open land between the Agricultural Hall and the Polly Hill Arboretum in West Tisbury and announced plans to build a spacious new facility. That effort was soon derailed by, among other things, competition with several other institutions’ capital campaigns and a decidedly mixed reception to the idea of an up-Island location. Leadership at the museum abruptly changed and then changed again. With notably less fanfare, the West Tisbury land was resold in 2011, and with the help of what former board president Elizabeth Beim described as “three angels who trusted us,” the organization quietly purchased the Marine Hospital, an historic building itself in much need of re-branding and rehabilitation.

This time the museum’s purchase was met with approval from virtually everyone except the faction of Edgartonians who don’t want the museum to leave their town under any circumstances. The old campus in Edgartown, beloved though it is, has virtually no climate-controlled storage for fragile artifacts; it has cramped and poorly lit exhibition spaces; the library does triple duty as a research archive, a classroom, and a meeting room. And, there’s no parking. On the other hand, not only does the new location have adequate space and parking, a magnificent lawn, and sweeping views of Lagoon Pond and Vineyard Haven harbor, it is within walking distance of the year-round ferry terminal. As old and dilapidated as the Marine Hospital may have been, it seemed poised to become the perfect space for the new and improved museum.

But once again, to outside appearances, progress seemed to stall. Other than clearing the scrubby woods that had grown up around the old hospital and surveying the site for archaeological material, little seemed to be going on. Some momentum was undoubtedly lost with the untimely death in September 2013 of the charismatic board president, Sheldon Hackney. Out of the public’s eye, however, a lot was happening. There were important and popular exhibits on the American artist Loïs Mailou Jones, the continuation of the Spotlight Gallery showcasing the museum’s deep collection on a rotating schedule, the continuation of the oral history project, and the publication of the historical journal The Intelligencer. Most notable, perhaps, educational programming for the public schools and for elders expanded dramatically, funded in part through a large and prestigious grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

And there was the daunting – and still unfinished – job of raising the funds required to take an old rundown hospital and turn it into a first-class museum. The early years of the economic recovery were not the easiest climate in which to work, but led by Beim of West Chop, who returned to the presidency of the board after Hackney’s death, and David Nathans, the previous executive director, steady progress continued. Discover, Explore, Connect: A Campaign for Transformation, as the museum’s capital campaign is officially called, aims to raise $24 million philanthropically for construction, moving, and an endowment. By the end of the summer, in the middle of which Beim handed the gavel over to Stever Aubrey of Edgartown, nearly $15 million of that had been secured, which prompted Wallis to exclaim, “Definitely full speed ahead!”

“What I’m excited about coming in,” Aubrey added, “is first of all partnering with Phil, because he’s got so much energy, but also I can’t wait to make this happen.” Though Aubrey and his family are longtime summer residents of Edgartown who recently moved here year round, perhaps appropriately, he first became involved with the museum not through its Edgartown campus but after visiting the Marine Hospital for a summer fundraiser on its grounds.

“It was a quintessential Vineyard night with all these people so passionate about the museum. We’re in this spectacular location overlooking the harbor with the Alabama and the Shenandoah in front of us. You could just feel the history,” he said. “I got so enthused about what this Island has represented not only for the generations of people who have lived here, the fishermen, the farmers, the artists, but what the Island’s part is in the world. As you get more entrenched in this place, you realize what a special place it is.”

With the trees cleared, land unearthed, and building façades cleaned, even the bare-boned, monumental building itself seemed ready at last for a new start.

The Marine Hospital itself is rich in history; it’s an exhibit of its own. Through the deserted halls, the paint-chipped rooms, and the abandoned bathrooms, one can almost feel the century of lives who passed time in its midst. On the shores of a harbor frequented by sailing craft from all parts of the north and south Atlantic coasts, thousands of sick and disabled marine seamen, soldiers, and their families were housed in the hospital, which was erected in 1895 “to provide medical and surgical treatment for seamen far from home and destitute.”

With the arrival of seaplane and helicopter service to larger veterans’ hospitals in Providence and Boston, the Marine Hospital closed in 1952. In a bizarre and somewhat macabre twist, in 1959 the buildings morphed into the St. Pierre School, a summer sports camp. Happy playful children, aged six to fourteen, enjoyed the sea air amidst the ghosts of wounded mariners of a bygone era. First as an overnight camp and then as a day camp, the St. Pierre School was a fixture of the town in its own right until it, too, closed its doors in 2010.

Early in 2017, work will begin on the renovation and restoration of the original 1895 Marine Hospital, the construction of a new gallery to house the Fresnel lens, and a barn-like “vessels and vehicles” building. The design, which was created by Oudens Ello, a Boston-based architecture firm that specializes in cultural and academic projects, can be seen at mvmuseum.org. According to the plans, the library and its archives, the education programs, some exhibits, and some collection storage will be moved to the new facility site, which will open to the public in the summer of 2018. After that, as additional funds become available, Phase 2 of construction will include building an additional state-of-the-art exhibition hall, and more climate-controlled storage capacity. In Edgartown, meanwhile, the historic eighteenth-century Cooke House will be retained as a stand-alone recreation of early Vineyard living, but the rest of the campus will most likely be sold.

Yes, the new site is in a more centralized, visible, and accessible location. And yes, the museum will have the climate-controlled environment, the storage space, the improved exhibit halls, and a dedicated classroom for the education department that it now lacks. But one lingering question remains: why do museums matter in the twenty-first century? And one more: how is a museum relevant today, in the age of at-your-finger-tips information?

It’s a question that even the new director found himself asking before taking the job last February. “My first thought was, I’m not really a museum guy; I’m more entrepreneurial,” said Wallis. Before coming to the museum, he had worked primarily in the conservation field, most recently as executive director of Pennsylvania’s National Audubon Society. “I saw

this big exciting project on an Island that I love in an industry that I wasn’t quite sure I understood well enough. So before I took the job, I went on a 2,000-mile journey to fifteen

different centers and museums up and down the East Coast to understand the why and the how, and what I learned was that the museum industry was going through a transformation. It was way more about people than it was about stuff. That excited me.

“Museums should be taking our past understanding, create current knowledge and life learning so that we act appropriately today for future practice. That’s the trajectory, and that’s what museums are doing today,” he added. “We have an obligation to the people of this Island, to the people who love this Island, to preserve and protect, but also to help people discover and explore new things about this place that they didn’t know before.”

“Those are great questions for us to answer,” echoed Ann Ducharme, the museum’s education director. “Museums, as I knew them growing up in the sixties and seventies, were these ivory tower sanctuaries where you stood there and you looked at things. They have dramatically changed in the past decade, and they’re still changing. We would like to think of ourselves as a place where discussions can happen. We are part of a movement called History Relevance.”

Ducharme uses the museum’s collections to create curriculum for the Vineyard schools, Windemere, and the greater Island community. Using a hands-on-history approach, the program currently reaches 2,200 students. Explains Ducharme: “Classes are the great bulk of what we do. We served over 3,000 kids this year; it’s not 3,000 unique experiences, however, because I met with one class of kids ten times.” The new location will give her a dedicated classroom for the first time. “It will be easier. All my stuff’s now in the basement, and we have to schlep it up every time we teach. We will be more accessible, with a huge place for our oral histories.

“Certainly, museums are a resource for learning,” she said. “We create context for visitors, students, people who live here. We are not an ivory tower of do-not-touches. One of the ways that our museum is really strong and important is that we have the stories. We are so lucky to have Linsey Lee as our oral history curator. That’s what makes us different; that’s what makes us special. This piece is huge; it’s like gold. We want to be a resource, but we also want to be a cultural center.”

It’s a phrase that often comes up in conversations with anyone involved with the museum these days. “It’s going to be more of a cultural center,” Aubrey said at one point. Or Wallis: “I want to define us as the cultural hub for the Island, with spokes to every township and to every community that we can.”

They partly mean that with its new central location, dramatic views, ample parking, and generous galleries, the new facility will hopefully attract the number of visitors to justify its effort and expense. Visitors at the current Edgartown campus reach 6,000 per year, with an additional 30,000 at the three lighthouses currently operated by the museum. The projected number for the new Vineyard Haven location is 15,000 visitors per year for the first three years, then growing rapidly thereafter. This is as compared to 60,000 visitors per year at the Nantucket Whaling Museum or 30,000 at the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine, both of which Wallis sees as role models.

“To me, the site is heritage and history,” Wallis said, a proud smile spreading across his face. “It’s education programming and interpretation, and it’s an experience of place. This is a marquee location. It will be a destination, a site experience.”

It’s not just about the number of visitors, however. Or even the quality of the exhibits or the obligation to protect the collection entrusted to the museum. Those goals are important, of course. “We have an obligation as people who are invested in this Island to preserve its natural beauty, to take care of this place so our children and their children can enjoy it,” said Aubrey. “Our obligation is to preserve our heritage.”

But Wallis, in particular, seems to be striving to articulate a broader unifying mission for the organization. “It’s not about moving a building from Edgartown to Vineyard Haven. The Vineyard is incredibly diverse in so many ways, but if we don’t connect the spirit of the Island, which is very environmental, the sea, the land, the air, to its people who create the thoughts, beliefs, and practices, which is culture, then we’re missing the key link here.

“It’s about our Island.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)