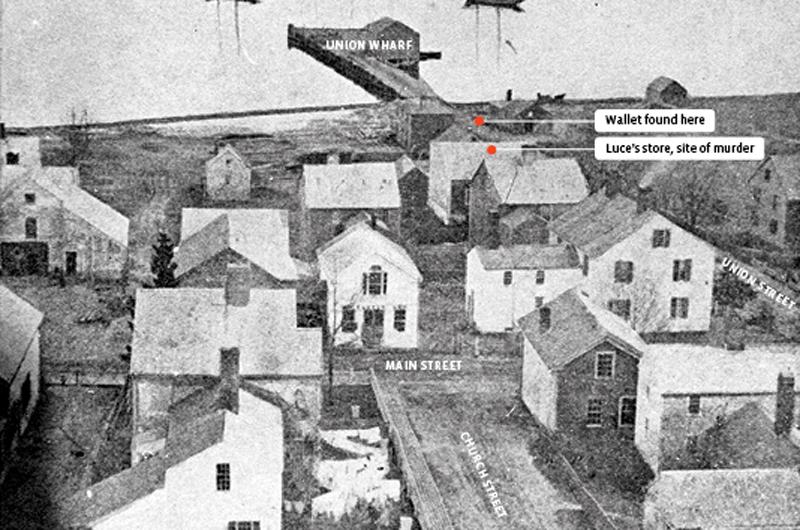

When you walk down the gangplank from the ferry in Vineyard Haven and turn to face the town, almost the first thing you see is an ancient killing ground.

About where Candy Haven stands today, just beyond the information booth, stood the grocery and dry goods store of William Cook Luce. Two nights before Christmas in 1863, Luce was standing on the customer-side of his counter with his back to the door, wrapping up three sticks of candy and preparing to close up shop for the night when someone came into the store, took a hatchet from the wall, and swung it into the back of his head.

The blow cut into Luce’s skull, a little to the right of center, burying the blade up to the handle. Luce fell. He lay with his feet toward the counter and head toward the door. He was almost certainly already mortally wounded, but to be sure, the assailant or an accomplice reached down and cut the wounded man’s throat with a knife twice, severing arteries, trachea, muscles, and vertebrae. The killer or killers then pulled a wallet from Luce’s pants pocket and ran to the harbor, but dropped the billfold, spilling cash and coins on the road down to the beach.

It was about 7:30 p.m. At some point a light snow began to fall.

Roughly three hours later, shortly after ten o’clock, Luce’s twelve-year-old daughter, Sophia Jane, known as Jennie, went to the store to see what was keeping her father. She found him on the floor, nearly beheaded. She screamed. Her uncle, James Luce, and grandfather, Jonathan Luce, who lived next door, came and saw the carnage. James ran up Union Street to Main Street and called a neighbor, Rodolphus W. Crocker, and a physician, William Leach, from their beds. From the store they summoned the coroner, John W. Holmes Jr. He examined the body around 11:40 p.m., and the two doctors decided that Luce had been dead about two hours. He was fifty-one.

Though no one was ever convicted or even tried for the murder of William C. Luce, there is almost no mystery years later about who did it and why. According to testimony at the coroner’s inquest, a resident named John Lewis bought flour at Luce’s store at about five o’clock that evening, but said he’d come back to pick it up after visiting a friend at a vessel tied up at Union Wharf, now the Steamship Authority pier. En route to the wharf, he saw three men in a yawl boat, beached. When he returned to the store about half past seven to pick up the flour, Luce told him he expected no more customers that night and began to put up the shutters on the windows. As Lewis left the store, heading up Union Street, he heard and saw three men walking up the street behind him. All three, Lewis said, were talking and laughing as though intoxicated.

“Let us go in here,” Lewis heard them say. He turned and walked on.

The next morning, about the time that news of the murder was racing across town, a ten-year-old boy named Gorham B. Smith found Luce’s wallet in front of the cooper’s shop, which stood about halfway between the store and the beach. A few bills and coins had fallen out, spreading in the direction of the water and the ships laying at anchor in the harbor.

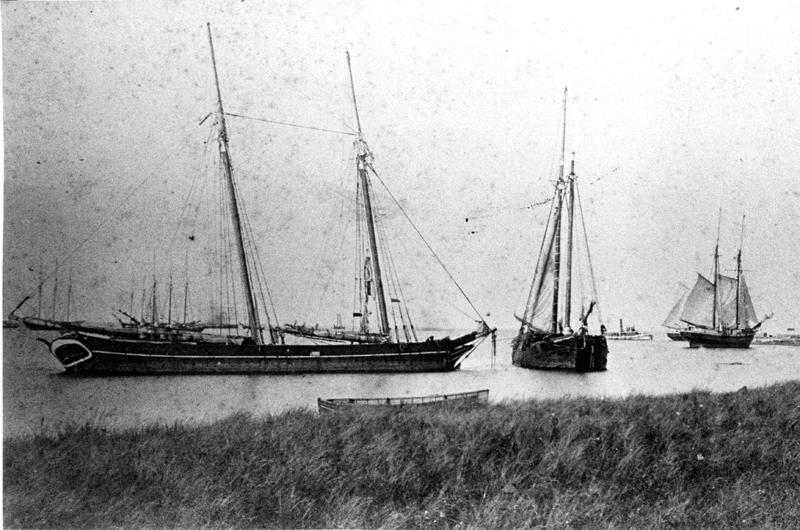

The implication was obvious. In the nineteenth century, the waters between New York and Boston were among the busiest in the world. The Cape Cod Canal, a prospective shortcut between the two cities, was still only dreamt of, so the coastal route took sailing ships through Vineyard and Nantucket Sounds, and around the outer Cape. If the winds or currents went against a voyage, Holmes Hole was one of a few places to drop anchor and wait for a more favorable breeze or tide. On these layovers, sailors came ashore, cavorted in town for a few hours or days, and then sailed away, leaving their deeds astern.

On the night of the slaughter, the harbor was filled, yet the town was quiet. Testimony suggests only eight or ten people saw each other on the streets of the village the whole night long. A little snow fell, but the morning after the killing nobody saw footprints leading to or from Luce’s store. That day, Constable Richard L. Hursell arrested the crew of the S.K. Hart, a schooner in the lumber trade out of Bangor, Maine. Why this ship was singled out is not remembered in the record, but Hursell searched the vessel and found no evidence linking its crew to the killing. The sailors were freed and the S.K. Hart sailed off.

With the most plausible suspects now beyond the horizon, fear descended upon the town. It was possible that the killer was still on the Island, after all. “What protection can man have if the ruffian shall, in the darkness, stealthily deal the death blow and live to repeat the infernal act,” asked the Vineyard Gazette on New Year’s Day 1864. An ad hoc police force was organized, but the officers and acting chief, R.W. Crocker, were all civilians with no known training in criminal procedure or law; the last man held for murder on Martha’s Vineyard was a transient arrested in 1806, according to files at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Vineyard Haven – in those days Holmes Hole – needed a culprit.

On January 4, the town offered a reward of $500 – the equivalent of about $7,700 today, at a time of year when few people in Holmes Hole would have been earning much money at all – to anyone who offered information that would lead to the arrest and conviction of the killer. Instantly, it seems, every citizen in town turned detective. The Gazette in Edgartown found itself besieged by busybody Holmes Hole residents urging the paper to publish rumors as facts. By January 15, editor James M. Cooms Jr. decided that he had had enough.

“Suspicion, horrid monster, poisoning many a good name with his foul breath, gathers up the thread until he weaves it into a net which at last catches up its victim and he is subjected to the tribunal of investigative minds,” Cooms wrote.

“Merely brought up for investigation, and before sufficient evidence can be obtained to arrest him, by the people he is pronounced guilty, and his name is handed back and forth, the press promulgates it and thus the man, even if further investigation proves his innocence . . . is branded with a calumny that will be hard to recover from….

“[E]very man is innocent until proved guilty, and we would have none usurp the prerogative of the law by imposing stories upon the press, and fixing the guilt upon a man against whom the evidence, which is circumstantial, is not strong enough to cause his arrest.” There could be no doubt in Holmes Hole which man Cooms meant; before the reward was even announced, the verdict in the port had settled on their neighbor Captain Gustavus Smith.

Smith sailed schooners up and down the coast, but had retired from the sea in 1862 to care for his invalid wife, Merinda. He was a devoted husband, “a very kind and humane man – always good to his wife, who is sick and irritable,” testified her physician, Dr. George T. Hough, at a judicial hearing that followed the inquest. His pastor at the Methodist Episcopal church agreed. “I always found Smith ready to gratify his wife in every wish more so, probably, than was to her advantage,” said the Reverend M.P. Alderman.

After a year ashore caring for his wife all day, Smith had no job and little money. In the fall, a woman who had helped him by attending to Merinda at night left. For many weeks into December, Smith walked across the village in the evenings asking women to come watch his wife, presumably so that he could have a little time to himself. Often he took a pitcher with him on his rounds and filled it with milk at the Joseph Adams household.

So often had Smith leaned on the charity of his neighbors that on the night of the killing, a woman named Charlotte M. Peakes saw him coming south on Main Street and turned her back to keep him from seeing her. At least seven other people were certain or fairly sure that they saw Smith walking the streets or visiting their homes that night; two saw him with his pitcher. Two others – one happened to be Constable Hursell – were at Smith’s house that evening and saw him return around eight o’clock without a woman to attend to his wife. He looked and behaved normally.

Even so, forty-eight hours after the murder, with the S.K. Hart and the three sailors gone and almost no evidence left behind on which to build a case, sentiment was moving against Smith. On Christmas Day he asked two villagers if he could borrow their horses to collect wood. Both refused him coldly. Whether this was because they already suspected him or had simply grown weary of his asking for favors is unknown.

Either way, Smith himself appears to have had little sense of how his position in town was changing for the worse. For days afterward, he acted cavalier about the killing of Luce, a respected citizen and personal friend. Willis Howes recalled Smith saying “there had been much excitement or feeling about the murder, and then said if people were familiar with such sights as he, they would not think so much of it.”

This was in keeping with Smith’s behavior. His sense of humor could be allusive to the point of mystification. “Jocose,” the acting police chief R.W. Crocker described him as. “Light and trivial in conversation on almost every subject, though not in regard to murder or perjury,” Dr. Hough testified.

It was true that Smith had harried people for months about sitting with his wife. But in the next two weeks what really damned him was that peculiar sense of humor, grounded as it so often was upon non-sequiturs, odd allusions, and a lack of feeling for the situation around him. To the acting chief, Smith said he wanted a place on the temporary police force – if it would pay. To the coroner he noted that the horse of a Mr. Taber had just died and asked if an inquest would be called for the animal. To one neighbor pained by the killing, he said that “Napoleon was buried with his face downward,” a sign of disrespect for the dead. To another he joked that Luce may have left himself vulnerable to attack: “The heathen leave open all their doors, but Christians bar out the people with bars of iron,” he said.

When Smith was called before the coroner’s jury on January 8, 1864, he could not remember where his search for persons to watch his wife had taken him back on the night of December 23. But now he realized that doubts were closing in around him. Before his testimony, he asked Joseph and Cordelia Adams whether he had come to their house that night for milk. They said no. “The Devil!” said Smith. “I don’t know where I was that night, but I think I came here for milk.” He was called before the inquest twice more and, his anxieties rising, made the mistake of telling conflicting stories about where he went the night Luce was killed.

At the later judicial hearing, presided over by Justice Jeremiah Pease Jr. of Edgartown, and with Islanders from as far away as Katama and Menemsha filling the room as spectators, witnesses testified as to whether they saw Smith wearing a hat that night, whether he was carrying the pitcher, whether he sampled a pot of hulled corn simmering on a stove at his sister and brother-in-law’s home. The most melodramatic testimony came from William L. Mayhew, one of the appointed policemen, who reported that he had followed Smith around for days after the murder. “My object in accompanying Capt. S. was to do my duty as a policeman, to detect the rogue if I could,” he said.

The estimated time of death was 8:30 p.m., though forensics were imprecise in those days, and the three sailors were seen entering Luce’s store an hour earlier. From the testimony at both the inquest and at the later hearing, it was easy enough to establish Smith’s whereabouts on the streets or at various neighbors’ homes between 5:30 and roughly 7:45 p.m. Furthermore, Constable Hursell and a neighbor, Ann Crowell, were at Smith’s house when he returned at 8 p.m. or a little after. Given the gruesome manner of the killing, it is nearly impossible that he could have committed it in the intervening twenty minutes and returned home to greet the constable and Crowell in clean clothes. And if he went out again and killed Luce in the half hour after Hursell and Crowell saw him, there was no explanation why he would then have ran in the opposite direction from his house, dropping Luce’s wallet near the beach where the yawl boat and three men were seen earlier that evening.

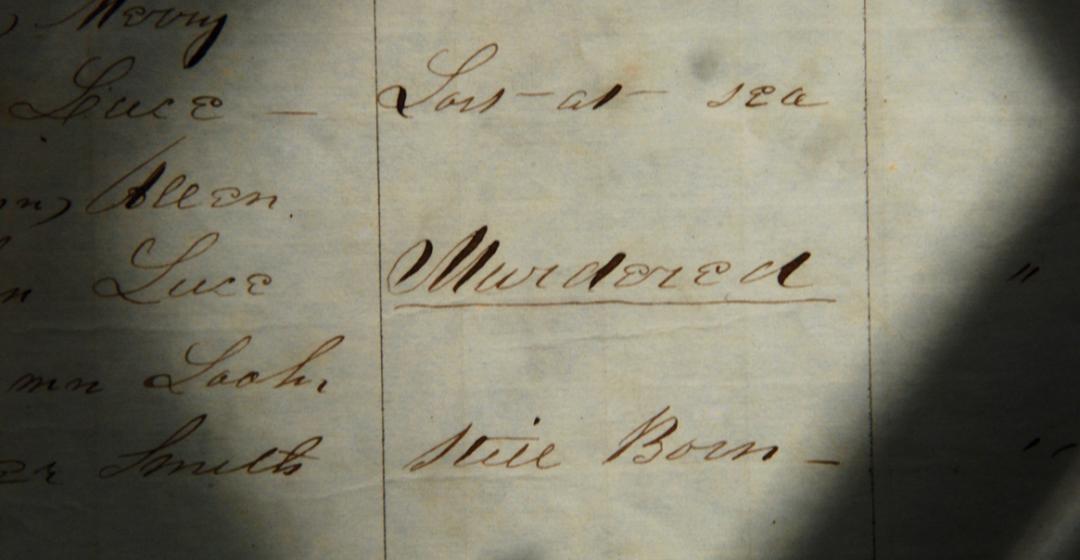

Nonetheless, Justice Pease ruled that Smith should be arrested and held in the county jail until the sitting of superior court in May, when an indictment might be handed down. Because the charge was murder, there would be no bail. He was taken to the jail, which was then located in a corner of the county courthouse lawn in Edgartown. An indictment was filed on June 1, 1864. His wife Merinda had died six weeks before. The cause of death was uterine cancer. She was forty-one.

“The condition of Mr. Smith’s family elicits a great deal of sympathy for him,” said the Gazette.

Murder trials were heard on the mainland, and based on the schedule at the time, Smith faced the prospect of a full year in jail before his case could even be tried. In the meantime, George Marston, district attorney for southeastern Massachusetts, decided that the case against him was preposterous. He told Smith’s principal defense attorney, Thomas M. Stetson of New Bedford, that he had no intention of prosecuting Smith. A special sitting

of the state supreme judicial court was to be held in Taunton in October 1864, he said, and given the circumstances it might at least release Smith on bail. The Edgartown jailer, Samuel S. Daggett, was instructed to take the prisoner to Taunton for the hearing.

The denouement was perfectly ironic. Writing nearly fifty years later, attorney Stetson recalled that “The old jailer, Daggett, nearly eighty years old and almost blind, had a lot of trouble getting across the tracks and through the frisky locomotives at Taunton and never could have succeeded had not Captain Gustavus taken him by the shoulders and steered him as you would a wheelbarrow. There were hundreds at the depot to see ‘the Vineyard murderer’ arrive. Naturally the crowd thought Daggett was the criminal, and that the hale, stout captain was the constable in charge. . . . One woman next to me sung out, ‘Oh I know he is guilty from his hang dog look.’ ‘How could such an old man kill anybody?’ ‘I hope the officer won’t let him escape,’ etc. etc.”

The court heard what evidence there was – and overwhelmingly wasn’t – and promptly released Smith on his own recognizance. No trial was ever held. On November 4, 1864, the Gazette published a letter from him in which he thanked jailer Daggett and his wife for their solicitous treatment during the ten months he was held. He also thanked “the people of Edgartown and other parts of the Island for their kind attention to me,” and especially “the young lady (whose face I never saw) who supplied me with reading matter, thus, like an angel of mercy, contributing to the comfort of the prisoner.”

No longer needing to care for his wife, he returned to sea and died five years later in Eastport, Maine, on June 18, 1869, at the age of fifty-five. He is buried with his wife, Merinda, and a daughter and son-in-law in Vineyard Haven. At his death he had no will, no money, and no longer owned his home at Owen Park. His estate listed eleven sets of personal items, including one lot of old bedding, two pairs of old boots, a tea set, a trunk, and one fork. The value was $39.50.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)