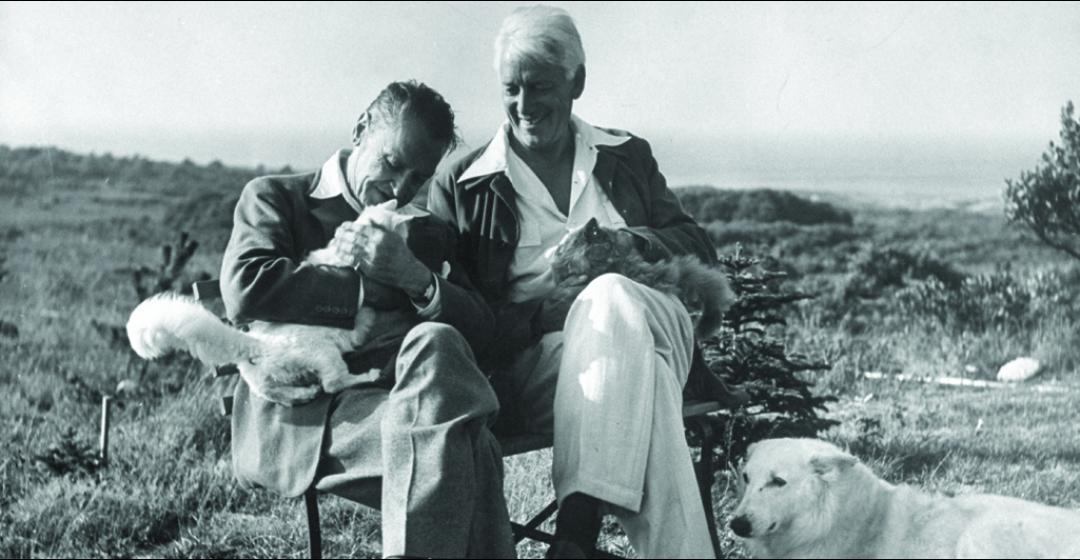

In September 1944, Life magazine published a glossy spread on the seventy-year-old W. Somerset Maugham, “Willie” to intimate friends, “the most eminent of living English novelists” to the world, who had been spending his recent summers on Martha’s Vineyard. Several pages of photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt showed Maugham in his Island life: enjoying breakfast in bed at the Colonial Inn in Edgartown; drying off after a swim on Chappaquiddick; viewing a new painting with Thomas Hart Benton; dozing in a hammock at the artist’s home. In the summary portrait, Maugham sits on a rock on a sandy beach, wearing shoes and socks, reading a book on Renaissance literature. The world war that had brought him to the Island seems distant, insistent only in the margins of the Life article.

Maugham, who had been born in Paris to English parents, was living on the Riviera when the Nazis occupied France and commandeered his elegant Villa Mauresque on Cap Ferrat. Escaping by freighter to London where he was caught in the Blitz, he made his way to New York on the advice of his friend Winston Churchill, settled in at the Ritz-Carlton, and in mid-1942 moved to the Vineyard for the summer. He came for the seclusion, the sea-bathing and simple life, to finish an important anthology on modern English and American literature and, not incidentally, for the opportunity to forsake driving to save the tires on his car. It was rumored that Churchill had hoped, too, that Maugham, who had been an intelligence officer during World War I (he was sent to Russia to help stop the Bolshevik Revolution), would work to bolster America’s commitment to the war effort.

Maugham is an exotic and oversized character to encounter, many decades after the fact, in residence on a small and quiet Martha’s Vineyard. At the time of his visit, he was the most

prolific and financially successful living writer in the English language – second only to Churchill as the most famous Englishman in the world, it was said: novelist, short story writer, dramatist, screenwriter, and essayist, with more than thirty works of fiction and twenty-four plays already to his name, as well as a long and growing list of motion pictures adapted from his work, including, quite spectacularly, Bette Davis’s debut film of his 1915 now-classic novel Of Human Bondage. (Maugham rarely viewed his own films, but was always pleased with his ties to Davis.)

At the end of his first summer, amid a gathering of distinguished guests, Maugham was treated to the world premiere of the film of his novel The Moon and Sixpence at the Edgartown Playhouse, the first such gala on the Vineyard. The skies were dark under the wartime dim-out in effect on the Island and the setting was modest, but the audience glittered with the Hollywood producers and mainland press, a sampling of eminent composers, radical writers, and noted cartoonists, a vice admiral, an ambassador or two, the Boston Globe’s Emily Post and, briefly, Jimmy Cagney, who was leaving momentarily on a tour to sell war bonds. The Vineyard Gazette’s editor Henry Beetle Hough introduced Maugham, who made a rare address to his public and submitted gracefully to photographs at the Yacht Club reception.

Behind his gentlemanly façade, Maugham was a complicated and famously private man, which makes catching him off guard in the little-known wings of his life seem all the more seductive. In the Gazette archives, small and random details about his days are engaging on their own – Maugham reads Plato or poetry before breakfast; plays passionate canasta and bridge; has met Katharine Cornell, America’s First Lady of Theatre, at a clambake. Such snippets, like flares, lead the way into meaningful chapters in his biography. Maugham’s personal pleasure in literature, for example, lies behind Great Modern Reading, the anthology he compiled during the summer of 1942, as well as his fervent campaign to encourage the wider distribution of good books in America. His passion for

bridge would result in his writing the introduction to Charles Goren’s classic, The Standard Book of Bidding, which in the 1950s was reprinted in Goren’s weekly column in the new

magazine Sports Illustrated. Cornell, who starred in Maugham’s 1927 drama The Letter, would star in the 1951 revival of The Constant Wife.

At times during these years, Maugham seems to be cropping up everywhere, the man of the hour, with features in major dailies, a short story, a two-part “Profile” and a Talk of the Town piece in The New Yorker, and the dozens of articles he wrote to promote the joy of reading in popular magazines like Redbook or the Saturday Evening Post. Maugham had stated in his first interview in the Gazette that he was distressed at the negligible number of bookstores in this country, but was excited by the example of his friend and publisher Nelson Doubleday, who had initiated the sale of books at F.W. Woolworth. (Maugham’s own 600-plus-page hardcover anthology later sold there for 69 cents.)

With the publication of The Razor’s Edge, which appeared at the top of bestseller lists in the summer of 1944, Maugham achieved a new level of fame in America. He was also a familiar sight around Edgartown, the erect and distinctly English visitor with his closely cropped mustache and faded blue beer jacket, who enjoyed a brisk afternoon walk and a punctual cocktail. To locals he brought to mind a retired professional soldier, or to those who knew him better, a character from one of his own novels. The Gazette had welcomed Maugham warmly: “His arrival at once goes into an unwritten but well remembered record,” it commented with obvious pride in the July 28, 1942 edition, and its pages kept track of the author for decades to come, commemorating his birthdays, recalling his candor and casual elegance long after he had returned to France and the days of wartime had faded.

Maugham, we can assume, was happy as well as productive on the Vineyard, although there is virtually no mention of his experience in his work. He liked the sea, which he described as warmer than the English Channel and not as blue as the Mediterranean. He liked the perspective on North Water Street from the wide porch of the Colonial Inn. He liked his daily naps. Maugham had traveled the world widely for many years, always in search of stories and peace of mind, but he never liked to spend more than three months anywhere outside of France, which he loved, which gives Martha’s Vineyard a clear distinction. After the war, Maugham expressed his gratitude to America for its hospitality as well as its early support of his work when he gave the original manuscript of Of Human Bondage, the semi-autobiographical novel that he had drafted in pen in sixteen leather notebooks, to the Library of Congress. Deep in annals of the Gazette, in the very least, Maugham still has his charmed place. A reporter who has the intonation of Henry Beetle Hough wrote in July 1943: “This island, more than most places of the earth, takes pride in its visitors – which is perhaps an Island prerogative.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)