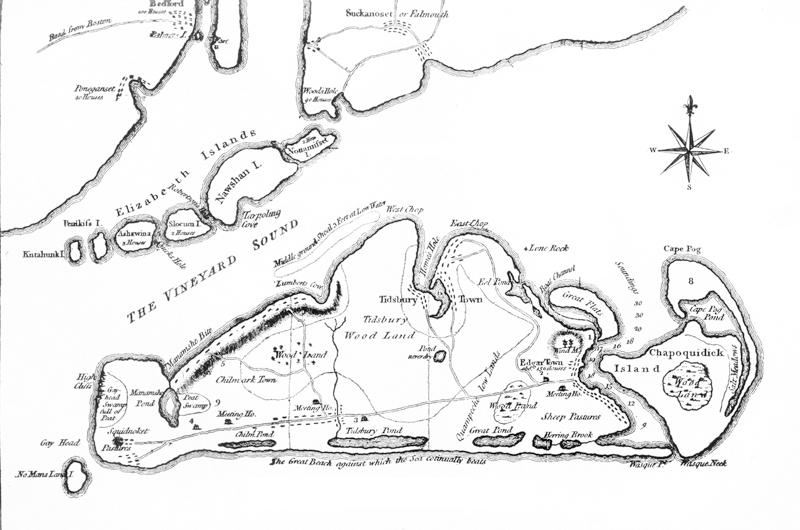

On September 10, 1778, townspeople standing on the high ground above Holmes Hole (Vineyard Haven) were suddenly transfixed with horror. Sailing toward the harbor, coming straight at them, was a British invasion fleet of seventy-seven ships, the Union Jack fluttering at their mastheads. Word soon spread that the same miscreants who had devastated New Bedford and Fairhaven just days before were about to wreak havoc on Martha’s Vineyard.

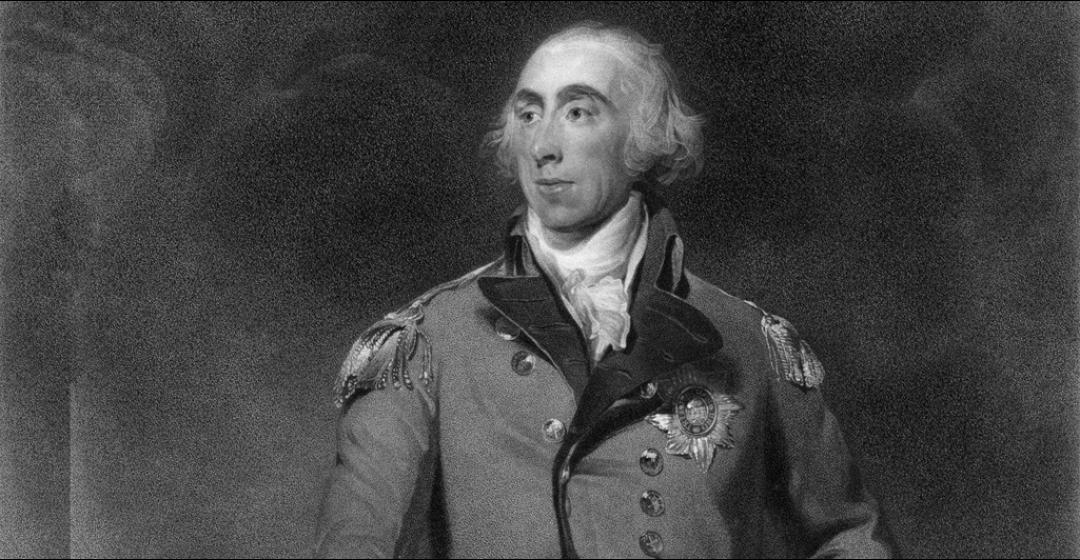

The number of hostile vessels was sobering enough, but the man that Islanders suspected was leading them was the most feared officer in the British army – forty-nine-year-old Major General Charles Grey, reputed to be the most bloodthirsty soldier in the King’s service, cruel and heartless, with a deep-seated contempt, indeed, hatred for Americans.

Grey’s reputation stemmed from an attack he led during the battle for Philadelphia in the fall of 1777. On September 20 of that year, he won a stunning victory at Paoli, Pennsylvania, over a 1,500-man detachment of the American army, under one of George Washington’s best fighters, Major General Anthony Wayne. In the dead of night, Grey’s regulars took the patriots by surprise, attacking Wayne’s encampment with a much stronger force, using primarily the bayonet. Grey was said to have stabbed to death hundreds of sleepy rebel fighters before they knew what struck them. The ghastly slaughter was reported far and wide as the depraved act of an officer devoid of human feeling.

The accounts of the event that reached the Vineyard, although widely believed – even to this day – were grossly exaggerated. Grey did surprise Wayne’s troops, but patriot sentries and frontline defenders fought back hard, holding Grey, while Wayne and most of his men escaped. Patriots on the frontlines fought so aggressively that Grey could not pursue the bulk of Wayne’s men, as they carried out an orderly retreat. Wayne estimated that forty-two were killed, another thirty wounded, and eighty captured – a dreadful loss, but a far cry from the wild estimates being bandied about.

Both sides made extravagant claims about what happened. General William Howe, the British commander in chief, bragged that Grey had bayoneted 400 hapless rebels. Grey’s aide, Major John André, who later became famous as the man who managed Benedict Arnold’s betrayal, proclaimed that 300 rebels were skewered. Far from disagreeing with this blatant propaganda, patriot publications screamed that the depraved redcoats did indeed bayonet 400 of Wayne’s men without mercy.

Grey’s reputation was blackened further by accounts of what happened at New Bedford and Fairhaven during the first week of September 1778. Reports circulated that he had sailed into Buzzards Bay and swept into the Acushnet River, burning whatever river traffic he encountered, before laying waste to New Bedford’s waterfront, destroying wharves, warehouses, and ships. The fires he carelessly set blew into town, burning homes and churches.

Grey then turned on Fairhaven, directly across the Acushnet River from New Bedford. By that time, the town’s militiamen – 150 strong – had gathered to defend the town. The intrepid Major Israel Fearing led them. No matter how powerful the British might be, Fearing intended to stand his ground and fight, and so did his men. General Grey, however, ignored them, destroyed Fairhaven’s waterfront, as he had New Bedford’s, and then left. Word got around that Major Fearing and his men had driven the British off, which, of course, was nonsense. Grey had over a thousand regulars. He did not leave because of the militiamen; in fact, he spared them.

Grey’s avoidance of the Fairhaven militiamen – or any rebel fighters for that matter – did not go over well in London. The man directing the war for the king and the British ministry, Lord George Germain, the secretary of state for the American Department, would have liked Grey to make an example of Major Fearing’s militia and kill every one of them.

Punishing raids on defenseless coastal towns had been an essential part of British strategy from the beginning of the war. London had ordered retaliatory attacks on every coastal community along the eastern seaboard, particularly in New England, to terrorize the inhabitants and keep the militiamen home defending their communities, rather than joining Washington’s army or manning the hundreds of privateers that were threatening Britain’s trade, the backbone of her economy.

Some British commanders felt no qualms about destroying rebel towns, killing innocent people wholesale. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, for instance, on June 17, 1775, General William Howe, who was in charge of the attack, allowed Admiral Samuel Graves, the naval commander in Boston, to burn down Charlestown, a settlement older than Boston, by hurling flaming projectiles known as carcasses into the village’s wooden buildings, igniting fires that destroyed every structure, and killed anyone in them. The same admiral ordered the destruction of Falmouth (now Portland, Maine). Lieutenant Henry Mowat dutifully carried out the order on October 18, 1775. He directed four warships to fire on the defenseless city, creating a gigantic ball of flame that consumed it and left its citizens either dead or homeless. Norfolk, Virginia, was also burned.

As London saw it, these raids would strike terror into the rebels and force them to submit. Many British commanders, however, thought the strategy was not only immoral but idiotic, since it created far more rebels than it eliminated. Patriots had shown time and again that they were not intimidated by this kind of senseless killing. General Grey was among those who thought terrorizing the coast was counterproductive. So did his immediate superior in New York, General Henry Clinton, who replaced General Howe in the spring of 1778. Although Clinton was under orders to conduct raids, he kept them to a minimum. His generals understood his reluctance, and in carrying out attacks on New Bedford, Fairhaven, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket (although he never got to Nantucket), General Grey intended to inflict as few casualties as possible.

Of course, the people of Martha’s Vineyard had no way of knowing that. After hearing exaggerated accounts of what the British did to shipping in the Acushnet River and to New Bedford and Fairhaven, they prayed that the invaders would not come their way. But here they were, and townspeople were understandably scared to death. To their great surprise, however, the monsters had not come for blood and treasure, rape and rapine, but for livestock and any provisions they could find to ship to New York City, where they were desperately needed. General Grey assumed that if he arrived with overwhelming force, armed resistance from local militia would be unlikely. Of course, he intended to get the livestock he came for, and if there were resistance he would not hesitate to suppress it.

At this point in the Revolutionary War, a large percentage of New York’s sustenance came from England, Scotland, and Ireland, traveling across three thousand miles of the always uncertain Atlantic, which must have seemed more than a little odd to anyone familiar with New York’s countryside, which was filled with productive farms. The city had, in fact, never been short of food until General Howe and his brother, Lord Richard Howe, drove Washington’s army out of Staten Island, Long Island, and Manhattan in the fall of 1776. The Howe brothers’ gross mismanagement and massive corruption caused scarcity where none had existed before. And General Clinton carried on in the same fashion after them.

The root cause of New York’s woes was the insistence of these generals that martial law be imposed in all occupied areas throughout the war. Their American supporters (Tories) argued that military government was inherently oppressive and inefficient and urged that government be turned over to civilian control. But Howe and Clinton, although very

different characters in other respects, never paid any real attention to how the government was working and never relented. They were preoccupied with the war, and when they were not doing that, they were enjoying themselves with their mistresses and other entertainment. Howe loved to gamble, and Clinton, who was addicted to fox hunting, commandeered estates on Manhattan, Long Island, and Staten Island to provide the variety he expected. Thus, from the very beginning, New York City was a garrison town, with the military in charge of every aspect of life.

What that meant in practice was widespread inefficiency, rampant corruption, and lawlessness. The once genteel port city became a horror, where no one was safe from soldiers and officers who literally got away with murder and robbery. Local government, meanwhile, became rife with fraud, as the officers in charge took advantage of their power and feathered their nests in every way they could. The quartermaster general, for instance, would obtain horses and wagons from farmers for use by the generals in their campaigns, promising to return them or pay for them if they could not be returned. The farmers never saw their wagons or horses again, nor any compensation. Yet the quartermaster would bill the government in London as if he had paid the farmers, and then pocket the money. Wood and cattle were treated the same way, as well as every type of food. Officials amassed fortunes in a short time and returned to England wealthy, unconcerned with how their activity affected the war.

Farmers on Long Island soon retaliated by going on a silent strike. They stopped planting, except for their own consumption, and hid whatever they produced from the British. The result was massive shortages and soaring prices. Officials were forced to import

the necessities of life from home, making living in the city precarious. When French men-of-war blockaded New York Harbor for almost three weeks in 1778, interrupting the flow of all supply vessels coming from the British Isles, it created a real crisis, as hunger spread. The persistence of scarcity, where none should have existed, made General Grey’s mission to Martha’s Vineyard a military priority. It was imperative to secure food to keep the army and fleet in New York supplied, not to mention the thousands of people in a city swollen with refugees, including thousands of runaway slaves.

When Grey landed in Vineyard Haven, he met with Colonel Beriah Norton of the local militia and requested all the Island’s sheep, cattle, oxen, pigs, and any other provisions the Island could provide. He promised to pay for everything he took, which sounded nice, particularly when many people thought that given his reputation they were going to be butchered. He did not make payment in gold for what he took, however, but said the money would come from New York. Many believed him. It was certainly better than having their property stolen and the owners personally assaulted. At any rate, Colonel Norton could only agree to the terms. There was a gun at his head, and knowing General Grey’s reputation, there was no doubt in his mind that Grey would use it.

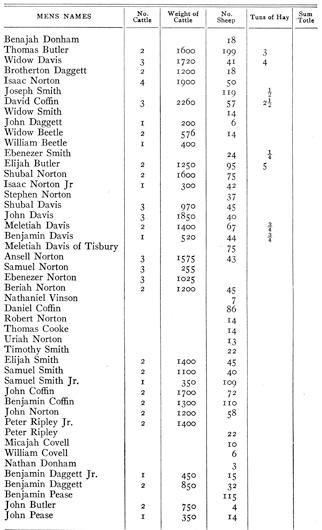

In the end, the people of Martha’s Vineyard supplied the general with an astounding 10,574 sheep, as well as 315 cattle, a good number of pigs and oxen, as well as provisions of various kinds. Grey was more than satisfied. He would return to New York with desperately needed food, and reap a handsome reward for himself, as well as a huge profit for the officials who received and distributed the goods. They must have had a good laugh when Colonel Norton naïvely showed up in New York to receive payment. He was told he would have to go to London, which he did, and received the same runaround, returning home embittered but wiser.

The people of Martha’s Vineyard, to their sorrow, soon realized that they had been robbed. General Grey might have profited, along with the officials who handled the goods in New York, but the Islanders were left with nothing. With the exception of a few minor

incidents that were probably inevitable with that many soldiers around, they had not been personally abused. Their pocketbooks, however, were certainly abused in order to feather the nests of British officials, who never seemed to get enough.