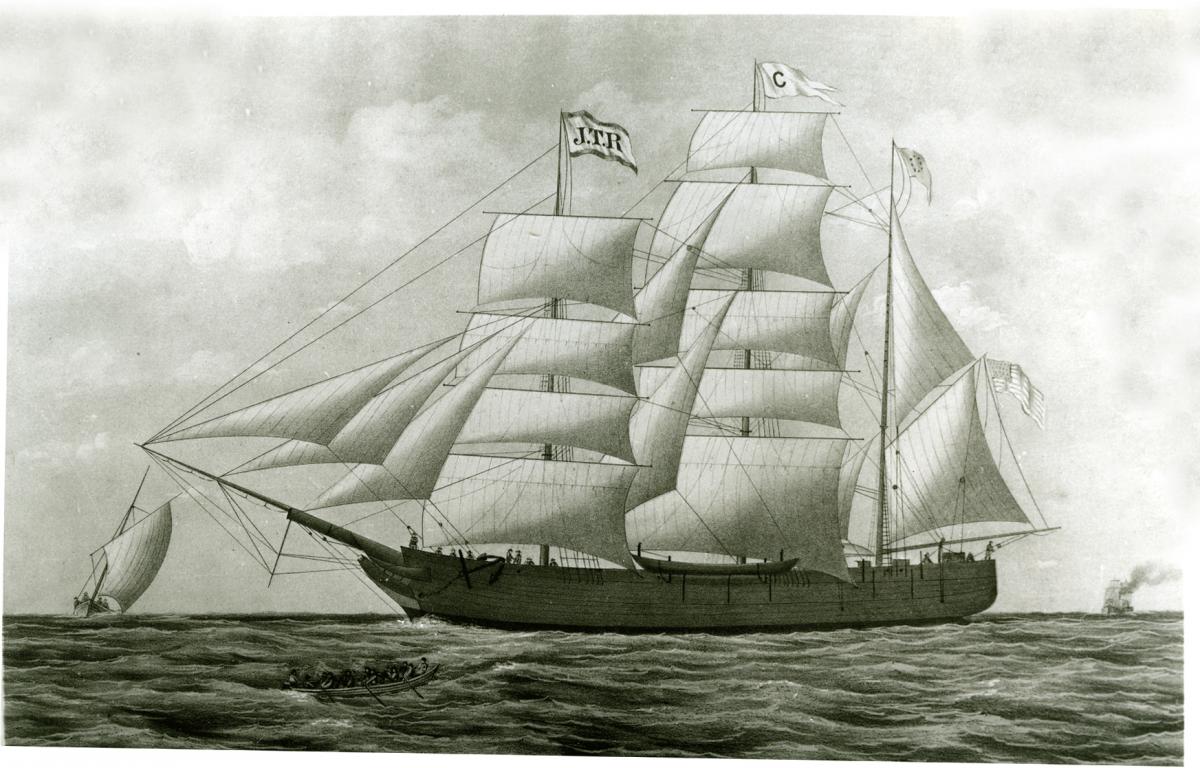

Catalpa: Whaling bark that in 1876 liberated six Irish revolutionaries from the British prison at Fremantle, Australia. Under Captain George S. Anthony, of New Bedford, and First Mate Samuel P. Smith, of Edgartown, the ship sailed on what appeared to be a normal whaling voyage. Not even Smith knew of his captain’s true plans, and the crew captured eight whales in the North Atlantic, before Anthony called Smith aside and said they were going fishing for political prisoners. He’d understand if Smith resigned, but added, “I hope you will stay by me and go with me. God knows I need you.” The Edgartown sailor thought for a moment and said, “Captain Anthony, I’ll stick by you in this ship if she goes to hell and burns off her jibboom.”

Catalpa: Whaling bark that in 1876 liberated six Irish revolutionaries from the British prison at Fremantle, Australia. Under Captain George S. Anthony, of New Bedford, and First Mate Samuel P. Smith, of Edgartown, the ship sailed on what appeared to be a normal whaling voyage. Not even Smith knew of his captain’s true plans, and the crew captured eight whales in the North Atlantic, before Anthony called Smith aside and said they were going fishing for political prisoners. He’d understand if Smith resigned, but added, “I hope you will stay by me and go with me. God knows I need you.” The Edgartown sailor thought for a moment and said, “Captain Anthony, I’ll stick by you in this ship if she goes to hell and burns off her jibboom.”

On the day of the rescue, Smith was in command of the Catalpa while Captain Anthony went in a whaleboat to collect the fugitives, who had escaped at the prearranged moment from a work detail. They were delayed in returning by a squall. By the time they did sight the Catalpa, a British gunboat was bearing down on her. Those in the whaleboat laid low to avoid being seen, while the Georgette steamed up to the Catalpa. “I don’t know anything about it,” Smith said when asked where the captain had gone. “Not by a damned sight,” he said when asked if the British could board.

When the Georgette sailed off, the fugitives resumed rowing hard for the Catalpa. But before they could reach her, a vessel filled with police appeared, and for a time it was unclear who would intercept the whaleboat first. “There were moments of suspense,” said a later account in the New Bedford Evening Standard. “Just before the police boat and the ship met, Mr. Smith steered the Catalpa between the boats, and as the whaleboat reached the Catalpa everything was thrown hard back, which stopped the vessel, the tackle was let down and fastened forward and aft on the boat. While this was being done the men sprang up the side of the ship by the grip ropes without waiting to be pulled up, the boat was instantly hoisted on the davits, and as the captain stepped over the rail, the police guard boat swept across the bow. The manoeuver was skillfully executed, and so well done as to merit the highest praise. The rescued men knew the police officers, and they crowded to the rail in great glee, waving their rifles and shouting salutations and farewells, calling the officers by name.”

There were a few more tense moments when the Georgette returned and threatened to fire on the Catalpa. “That’s the American flag,” Captain Anthony said, pointing to the banner waving at his masthead. “I am on the high seas; my flag protects me; if you fire on this ship you fire on the American flag.” Smith meanwhile, “denounced the colonel in good strong nautical terms,” as they sailed away.

Cape Higgon: Point on the Island’s north shore, roughly halfway between Menemsha Hills and Cedar Tree Neck. The name implies a connection to someone named Higgon, but deeds from 1663 show it was once called Keephikkon, an Algonquin word meaning “artificial enclosure,” or, roughly translated, “place where the white guys put up a fence.”

Concerned Citizens of Martha’s Vineyard: An organization formed in 1969 to oppose a wide range of developments perceived to threaten the character of Vineyard life.

Immediate aims included banning jet planes (which failed), banning big diesel buses on town streets (which sort of failed), and preventing the Steamship Authority from advertising for tourists to come to the Island (which absolutely, totally failed). The group disbanded in 1986.