Doug Kent shuffled around his workspace, pulling paintings almost as tall as he is from the nooks and crannies of his cramped studio. He is not quite sure how old he is, he said, but supposes he’s been alive for about sixty-seven years. In a later conversation, he guessed sixty-eight, then settled sort of definitively on sixty-nine. He gets this question a lot, he said with a laugh – possibly because he’s often lied about his age.

Kent recently misplaced his hearing aid, his seventh such device. He sometimes wears magnifying eyeglasses to compensate for blurred vision. He has the carriage of a much older man. But if his appearance is withered, his work is far from wilting. After more than forty-five years of creating art on the Vineyard, his current frailness stands in contrast to the sprightliness of his recent paintings.

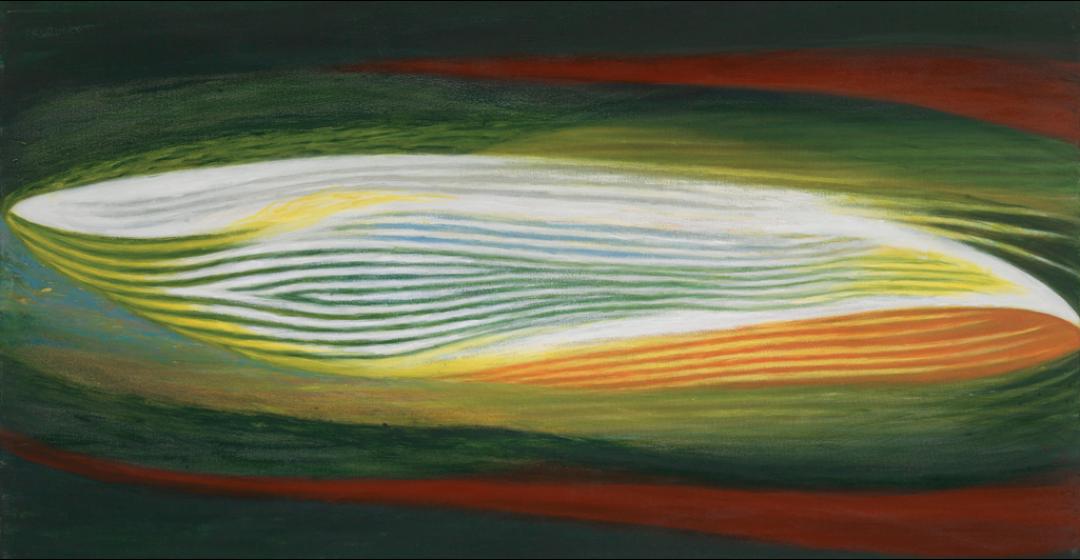

The work is abstract these days, experimental, and constantly evolving. He sat in an armchair and reflected on a large-scale painting that’s in process, a part of his “Mind Travel” series, inspired by the Buddhist musings of the Rinpoche at Bodhi Path Martha’s Vineyard. “He talked about life after death and the Buddhist belief of reincarnation,” Kent said. “Somebody asked what the mind looks like, and he said, ‘Nobody knows what the mind looks like.’ So I had this feeling I could make the mind look like anything I want.”

The subject, he said, is life after death and the separation of the mind from the body. “Some people have a hard time with it because they say, ‘If you die, doesn’t the mind die with you?’ But according to the belief it doesn’t. So I am having a good time just saying this is what the mind looks like or could look like.”

The series consists of about ten paintings, all variations on the same theme. The work is colorful and comprises many fluid, watery lines. One painting resembles the sun’s reflection on water, but is not meant to be representational. “All this interests me because I love lines and it’s an opportunity to put that into gesture,” he said.

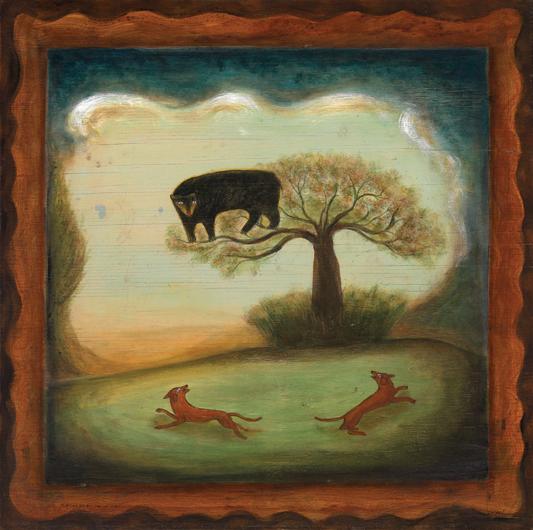

It’s not unusual for Kent to create numerous paintings exploring a particular theme or motif. For a time he painted many images of mysterious-looking bears. “I did one bear and then another one and then I just got into the image of the bear for whatever reason,” he said. He also paints a lot of fish. “I like taking one image and kind of pushing it,” he said. “It’s not just one painting and you’re done.”

Though his themes have changed, for Kent’s fans, there is something always recognizable about his work. Michael Van Valkenburgh and his wife Caroline have collected Kent’s work for twenty-five years. “I think his work touches on some very interesting traditions,” said Van Valkenburgh, who is a well-known landscape architect. “The one I love the most is the sort of place where folk art and surrealism – realistic representations that look slightly mythical or ghostly – overlap.”

Kent was raised by artist parents in Leicester, Massachusetts, outside of Worcester, and was exposed to art from birth. “I drew all the time on my own when I was smaller. It was always what I wanted to do,” he said. He cut a clear path to becoming a professional artist, attending the School of the Worcester Art Museum after high school. He’d been accepted to Yale, the University of Chicago, and Pratt Institute, but opted instead to remain near his mother. All three of his brothers had left home to fight the Vietnam War.

“It was a great little school because the Worcester Art Museum is a really great museum and the school was housed in the museum. So everyday I walked through the museum and would veer off. That was probably the best part of the whole thing,” he said.

He inadvertently landed on Martha’s Vineyard in 1965, after a sculpture professor of his had bought the Pequot Hotel and offered him room and board in exchange for his help refurbishing the place. In 1966 he held his first solo show – a collection of figurative drawings and watercolors – at the Pequot Gallery, which occupied a barn in Vineyard Haven.

His motives for staying and building a life on the Island were less haphazard, though for a time the lure of the New York art scene threatened to pull him away. He visited New York regularly, staying in SoHo, where he showed his work in a friend’s loft. “I used to call it dialing for dollars,” he said. “I would take work from my studio to New York and call people to come see it to try and sell the work. It was hard, though – because sometimes you would really hit it and get people in, and then private clients were wanting to come in at the same time as dealers and it was kind of a nightmare to schedule.”

Galleries that were interested in his work suggested that he make his home in the city, but ultimately the serenity of the Island won him over. It was where he wanted to raise his young family. “I was sitting in a park on Sullivan Street one day with this guy who was with his kids. He said, ‘Doug, you have to get a studio here,’ and I said, ‘John, my kids are swimming in Lambert’s Cove right now.’”

His work, too, benefited from his living on an island that offers room to roam. “I get a lot from nature – I love

to be out and walking and sometimes I walk for too long and I have to figure out how to get myself back,” he said. “But I gather a lot of information that way.” And so in the end, quality of life won over a perhaps more lucrative career. “I am not programmed for making connections and the business end of stuff,” he said.

Since Kent is uninterested in actively networking and marketing his work, most of his sales are made by word of mouth. “In the summer I get a lot of calls from people in Chilmark who come from all over the place saying, ‘I saw your work at Bob and Jane’s house, can we come by?’ I sell a lot of work privately, which is good because the gallery doesn’t take 50 percent, which is a killer,” he said.

He does occasionally have shows, both at his studio and in public places and various galleries on-Island. His work was on display during February and March at the West Tisbury Free Public Library and, as of press time, he was planning another opening and show at the Grange Hall in West Tisbury on June 29 and 30. “What’s good about a show is people bring things up that they see in your work that you don’t see or that wouldn’t occur to you,” he said. “And I like to let people know what I am doing.”

But showing and selling is just something Kent does to support the making of more art. He calls it the challenge of the craft. Asked what he considers most fulfilling, the answer is simple. It’s the craft and creation itself.

“The high point of the operation happens here,” he said. “If I had money I wouldn’t show, but you have to.”