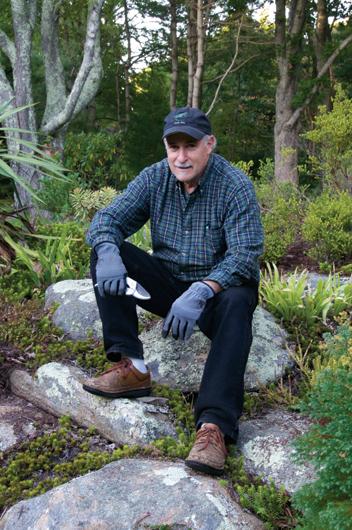

Until recently, rhododendrons were a part of creation that I rarely considered, except possibly at a shingling job site, wrestling with one next to a building while trying to get staging up. Then I met Peter Norris of Chilmark.

Driving onto his property off North Road, it’s immediately apparent that there is something going on there and it involves The Rhododendron. There are more than a thousand specimens spread over the landscape: you have your Rhododendron fortunei, your Rhododendron yuefengense, and don’t forget your Rhododendron yakushimanum. All in

plain sight!

“There are some here that can’t be found anywhere in nature, or in the world,” Norris told me, and then explained that with the help of his assistant, Suzy Zell, he works hard to propagate new hybrids, a process that can take up to four or five years to determine success or failure.

“How did this happen?” I asked.

“I don’t know...I really don’t know,” he replied.

“So, would you call it a passion or an obsession?”

“Oh, it’s definitely an obsession.”

He went on: “People ask me ‘Why rhododendrons?’ And I don’t really have a good answer. I guess, pardon the pun, I guess they kind of grew on me.”

With interest piqued, I did some rooting around of my own and discovered some interesting facts about the object of his obsession. Not only are some varieties edible, in the form of “Bog

Labrador tea,” for instance, but some species of rhododendron have played important roles in history – more specifically in the history of war. One variety is poisonous to humans, and as it turns out Greek soldiers were stopped in their tracks when they consumed honey from the pollen of such plants in 401 B.C. Pompey’s troops fell prey in 66 B.C. when they ate honey left behind by Pontic forces. So rhododendrons have been used as weapons. Thankfully, these days, in Chilmark, they are used for peaceful purposes.

As with all passions, Norris’s started small and eventually bloomed. Now a retired electrical engineer, he started planting rhododendrons in the late 1960s at his home in New Jersey. After that, wherever his career and life landed him, he would inevitably plant some

rhodies. In the 1970s, when he and his wife, Amy Rugel, were based in Cambridge, they began renting summer houses on the Vineyard, and in the late 1980s they bought a small cottage in West Tisbury.

There, of course, he started planting rhododendrons. Initially he planted some to shield the property from the road, but soon it got out of hand and they ran out of room. Today that property is a veritable jungle of his favorite plant. “There used to be a path and you could walk out to the road,” he said the day we went to visit it. “I don’t even know where it is now.”

Doing well in his career and with no more room to plant, in 2000 Norris traded up to a fourteen-acre piece of land with a nice house. He converted a garage that had been used as an animal shelter by the previous owner into a sunroom, and today over four acres of the property are dedicated to...you guessed it: rhododendrons.

From the beginning of April to July the plants begin to flower. But it is a slow process, and it isn’t until June that you see all of the colors, when the bulk of the plants begin to bloom.

According to Norris, the advent of the Internet was a major contributor to his transition from merely passionate to obsessed. “There were these sites from nurseries on the West Coast that had pictures of all the plants that were available and I would stay up into the early morning hours just looking at all these amazing plants. So much more than what was available at the local nurseries.”

He was hooked. But he still had more to learn. At home one winter about six years ago, he noticed a problem with some of his plants. They had big leaves that the wind would catch. By the end of the season all the leaves had been ripped off, which is when his scientific/engineering side kicked in and he decided he wanted to find a solution.

It so happened that around this time Norris took a trip sponsored by one of the rhododendron societies – yes, there are such clandestine groups lurking in our community – to China to see the varieties that grew there. While visiting a grove on a steep mountaintop, he noticed that some of the plants had very thick stems where the leaves met the branch, and it occurred to him that if he could learn how to cross this species with what he was growing on the Island, he could solve his problem with the winter winds. He became a propagator of hybrids.

Now, several years later, the process has taken on greater dimensions. It has become a year-round pursuit. In the spring Norris selects which plants to cross-pollinate based on flower size and color, fragrance, and various foliage attributes. The method is simple: you take the pollen from one flower and put it on another one. “Just like the bees,” he said. (Sort of: bees don’t physically cut the male portions of one flower off and rub it on the female portions of another, but the principle is the same.) “You only have a couple of weeks when they flower, the rest of the time you’re looking at foliage.”

In the fall and winter he and Zell harvest the seeds and process some for seed saving groups, such as the one at the West Tisbury Free Public Library. They also start somewhere in the neighborhood of 5,000 new seedlings, of which only 500 or so will be allowed to grow to maturity. “It’s really just a crapshoot; you may be throwing out the most incredible specimen,” he said. “You just don’t know.”

And you won’t really know for years. “It takes a year to get the seed. You pollinate in the spring and harvest the seeds in the fall. Then you don’t get the results for four years or so when the new plants flower.”

It turns out that there is a holy grail for rhodie wranglers. “Crazy as it seems, there are people who spend years and years and years going after the perfect hardy yellow rhododendron. It’s a search for the unattainable. It’s a quest. When a hobby becomes a quest...then it becomes dangerous.”

Part of the challenge with rhododendrons is that in the wild they live in a wide range of environments, from subtropical to mountain environments such as the Himalayas. But if you want the subtropical flower with the hardy northern species foliage, it’s again, as he said, somewhat of a crapshoot if it will work out.

“The joke is, it’s like the marine biologist who crossed the trout with the jellyfish hoping to get boneless trout, and instead gets bony jellyfish,” he said.

The passion has led Norris and his wife far afield to study the plants in their native habitats. “We’ve been to China, Japan, all over the place.” Nor are they alone. “There is this subgroup of people who wander around the planet looking at gardens in different countries.”

His garden is no exception. “I’m involved with the Garden Conservancy’s ‘Open Days’ program. There are garden tours; they bring people through. That’s an interest of mine, to share the interest.”

The more you talk to Norris, the more it becomes clear that he has developed more than an esoteric and practical regard for rhododendrons; he has come to care for his plants on a personal level. “You kind of get to know a plant by the time it’s a young plant,” he said. “Then it goes through its teenage years and then it’s off on its own, flowering.”

The plants require quite a bit of care to keep them thriving and safe, especially in dry summers. Yes, he could install automatic sprinklers (and after this summer’s dry spell, he is considering it). But, he said, “I have this crazy idea, I like to spray ’em. When you get into mechanical automated systems, you don’t spend the time with the plants. You get to the end of the week and it’s time to start all over again.”

Norris’s adventure with rhododendrons has not only caused him to discover other cultures on his forays, but at home here on the Island it has led him to appreciate the workings – and on some level the personality – of one genus of plant life. “These things, they want to live,” he said. “They have a tremendous drive to survive.”

Of course, as nature decrees, some inevitably don’t make it. Last year he lost one of his favorite plants to one of his implacable enemies: voles. “They had eaten the roots. It’s sad when one of ’em bites the dust,” he said. “It’s kind of like losing a pet.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)