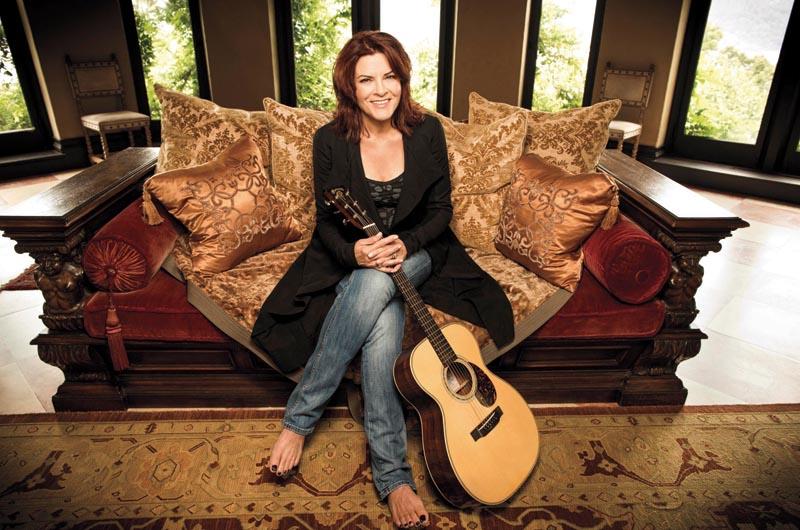

Cash Welcome

Country music legend Rosanne Cash will perform a benefit at Flatbread Company in Edgartown on July 1. Local radio legend Barbara Dacey (of WMVY and WCAI) caught up with her to talk of life, music, and Cash’s surprising connections to the Cape and Islands.

Barbara Dacey: So, I wanted to ask you about your coming to Martha’s Vineyard and the Cape and Nantucket. Do you have a tie to this area?

Rosanne Cash: I do! My son goes to camp on the Cape and this is his sixth year. He’s now a junior counselor – he’s a big giant teenager. So we’re out there twice a summer. I love the Cape so much! And Nantucket! I doubt if anybody really knows this, but my Cash ancestors were on Nantucket. William Cash was a whaler. It’s really incredible for me to go there. I have a powerful connection to Nantucket, the Vineyard, and the Cape. There are Cash names on the street there still. I am very proud of my connection.

BD: And on the Vineyard everyone is very excited about the fact that you’re going to be playing and it’s a benefit for such a great cause, something that people really care about.

RC: Isn’t it a great metaphor? Save the lighthouse. I just love that!

BD: What an amazing life as a songwriter and a singer, performer and recording artist, writer, mother, daughter, sister, friend. All of these thirty-five years of music-making, fifteen albums, and four books – a real full life! And your current record, The River & The Thread, seems like an album that was waiting to be made by you and [your husband] John Leventhal.

RC: That’s a nice way to put it, and yes. And yet I had to take every step in the last thirty-five years to get to make it. You know that saying – “Yeah, I wrote that song in two months plus thirty years.” And some of those songs do feel like they were waiting out there for me to get my skills refined enough to catch them.

BD: It seems that the record had to come at a certain time, when all of these…to use your image of a river… all these rivers and threads came together.

RC: It was a perfect storm of inspiration, really. I had gone through a couple of years that were difficult for me personally. Then I started going down to the South for a couple of reasons – to visit my friend Natalie Chanin in Florence, Alabama, and she was teaching me to sew. And then Arkansas State University wanted to restore my dad’s [Johnny Cash] boyhood home, so I was going down there to help them with that. And at the same time a lifelong friend of mine, Marshall Grant, who was my dad’s bass player in the Tennessee Two in 1955, he died on one of those first trips.

It was just this conflation of events and trips. The geography, and the emotional geography, was really powerful. And we started writing songs from it. I say “we,” meaning John and I, John Leventhal and I. He wrote the music, I wrote the lyrics, and it really was a marriage of ideas. Beyond the personal and the geographical, you start thinking about the Delta and everything that came from the Delta, William Faulkner to Robert Johnson, and realize how much of a debt particularly roots musicians owe to the Delta...it was very powerful to go to these touchstone places.

BD: Wow! You had so much to work with.

RC: It unfolded in a beautiful, natural way, and every trip we took down Highway 61, through Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, and even on into Virginia, everything had rich layers of musical opportunity.

BD: In your 2010 memoir, Composed, you wrote very honestly and with humor about your brain surgery in 2007. What an incredible, life-changing event!

RC: It focused my attention on what was most important to me, what I wanted to complete in this life. I have a friend, Ethan Russell, a photographer, and he said, “You have more to say and less time to say it.” That really came home to me with the brain surgery. I still feel as passionate about my work as when I started, I think more so. In The River & The Thread, I feel I’ve been working so hard and long to get to this record. It was an incredibly satisfying feeling to make it and to say, this is the best I could do at this time in my life. I don’t have any regrets about it. It was exactly what I wanted to do.

BD: It’s so wonderful to get a chance to talk to you before you make your way to the Island.

RC: I like these tours of the Cape and the Vineyard and Nantucket. It’s my kind of touring!

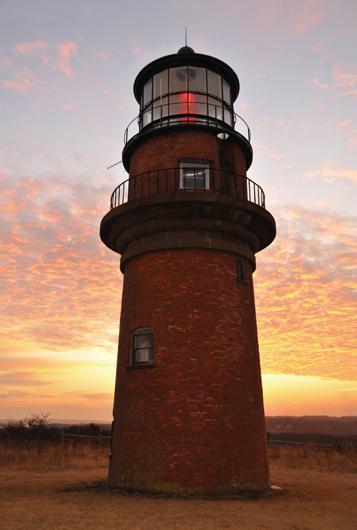

The Painter’s Light

Almost as soon as a lighthouse was built on the cliffs at Gay Head in 1799, artists began to make images of it. And they haven’t stopped. There are grainy woodcuts from the early 1800s, fuzzy stereoscopic images from the late 1800s, funky postcards from the turn of the century, art photos from the mid-twentieth century, and, we are willing to wager, paintings of the lighthouse done in every known style and medium. It makes perfect sense, therefore, that an art show to benefit the effort to save the lighthouse will be at the Gay Head Gallery (32 State Road, Aquinnah; 508-645-2776) from July 13 to 25. The show will feature art inspired by the historic light and the magnificent cliffs.

Way of The William

Nearly thirty years ago, when William Waterway first became involved in preserving Island lighthouses, the one that was falling into the sea wasn’t the Gay Head Light but its alter ego at the Island’s other extremity, Cape Pogue. In 1986, Waterway, who at that time was known by his given name, William Marks, testified in Washington before the late Congressman Gerry Studds’s Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Navigation that “it will only take one good winter storm or hurricane this late fall and it will be gone.”

To which the congressman replied, “so it might be important to [move the Cape Pogue Light] in Vineyard months,” as opposed to “Coast Guard months,” which they had established earlier in the testimony had a tendency to stretch on far longer than thirty days. “Yes, hopefully, if you can help,” Marks responded. And Studds said, “We will do our best.” The light was moved in 1987.

It wasn’t, however, the dire situation at Cape Pogue that brought Waterway to Washington that spring. A rumor that the Gay Head Light might be replaced by a strobe-topped steel tower had led him to try to convince the Coast Guard to lease that lighthouse to his nonprofit organization, Vineyard Environmental Research Institute. The deal, which went through a few weeks after his testimony before Studds’s subcommittee, included the Edgartown Light and the East Chop Light, and was the first of its kind involving active beacons.

With lease in hand, and friends – some of them well-known – in tow, the fundraisers began. At one in 1986, at the former nightclub Hot Tin Roof, Senator Edward Kennedy memorably prefaced his remarks saying, “William Marks called me some time ago and said, ‘Will you be a part of this effort to gain the lighthouse?’ I thought he said the White House and I joined on right away.”

Now, with the Gay Head Light in greater jeopardy than ever before, Waterway has published Gay Head Lighthouse: The First Light on Martha’s Vineyard (History Press, $25). The book is richly illustrated and is undoubtedly the most comprehensive look at the Island’s most famous beacon, from its beginnings in 1799 to today. Part coffee table book, part historical narrative, part anthology, part semi-channeled oral history, part personal memoir, part love letter to a tower of bricks, the book is pure Waterway.

Which is a good thing, mind you. And exactly what one would expect, after all, from a writer who, when he wasn’t hobnobbing with Island glitterati and saving lighthouses, was riding a horse 7,500 miles across the United States, studying Native American flute techniques at the feet of a Lakota master, writing poetry, playing ukulele, and, incidentally in 1985, founding this magazine.