There was a friend of mine, early on, who said, ‘Paint what you love.’” Andrew Moore leaned against a corner table in his Harthaven gallery, surrounded by his own work on one of the first warm days of the season. Behind him hung a nearly life-sized oil portrait of his daughter, Hannah, a parasol perched lightly on one shoulder. “I’ve maybe done one or two commissions, but generally, I paint things that are integrated in my life or ignite my imagination.”

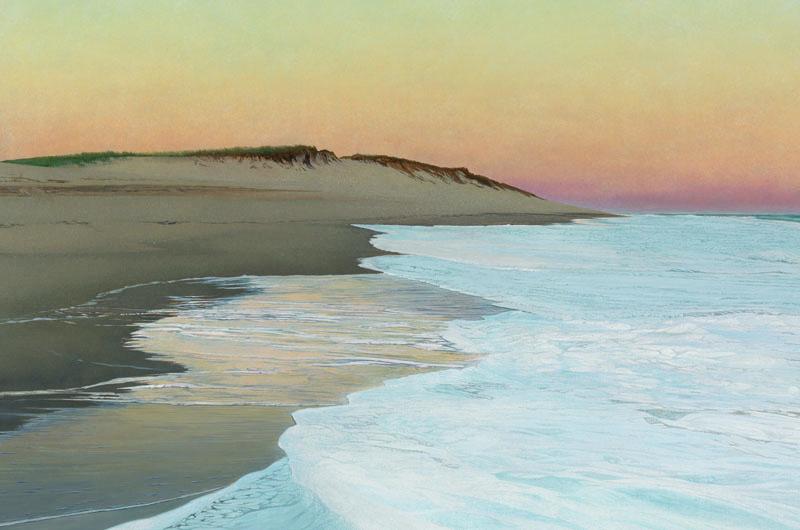

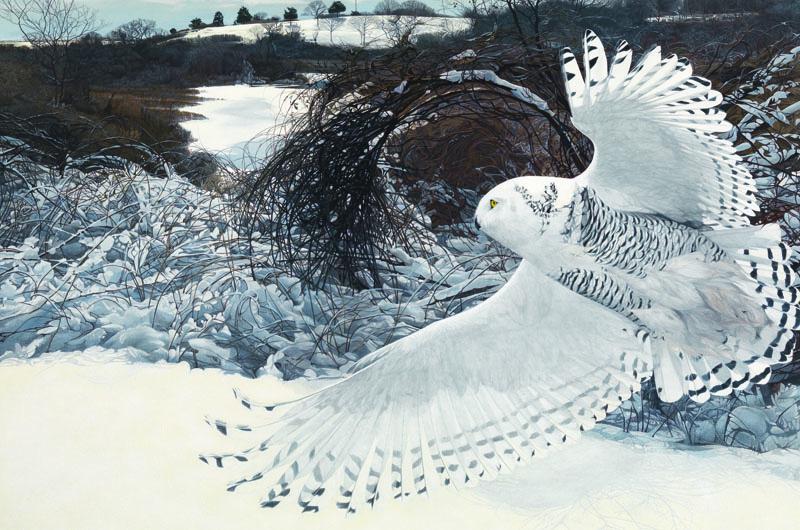

A quick glance at the walls around Moore’s gallery is, then, an intimate revelation. There is Hannah, and there is the ocean. There are seals. Birds. The Gay Head Cliffs. A whaleboat, mid-construction, parked in a waterfront shop. In short, there is life; specifically, a life lived outdoors on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard, in the company of family and friends.

“We’re very outdoorsy,” Moore laughed, when I inquired after the mountain of gear I had parked beside, stacked around a lean-to in the driveway: boats, boat parts, skim boards, a trailer. A basketball hoop presided over the main parking area, and from an overhang outside his front door, a Boston Bruins flag defiantly waved. It was not the quiet, austere habitat you might expect of one of the Island’s most esteemed nature painters. It appeared to be first and foremost a family home, which may be why, as of this summer, Moore will be rejoining the gallery circuit, after more than twenty-five years of representing himself from his own backyard.

“I like my privacy,” Moore said. “We [Moore and his wife, web designer Heather Goff] have three children that we raised here. I turned fifty and it was kind of a milestone. ‘What do I want to do? What’s really a priority in my life?’ A priority is being able to work unfettered and spend time with my family. Those are the key components.”

Which isn’t to say the work-from-home model hasn’t suited Moore well. After eight years of showing his work in galleries on the Island, on Nantucket, and in Boston, he opened his own gallery in 1990 for mostly practical reasons. “I found it challenging to make a living,” he remembered of those early years. “Galleries take fifty percent. I’m a pretty slow painter; I put a lot of time into each one, so that system was really hard. And since I lived here and I was in the studio all of the time anyway, it made sense.”

In the beginning, the gallery, a two-room structure with exposed beams and vaulted ceilings, was open for just a few months in the summer, and was used as a studio during the rest of the year. But Moore found he needed more of a physical separation between his work in progress and the finished paintings on the walls. He moved his studio into a room in his home, and kept the gallery open year round.

In many ways, going back to traditional galleries will make this distinction even clearer. Starting with a show in August, Moore will be represented by the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury, and will once again use the home gallery for painting. This, to Moore, is an appealing prospect. But it is the sales component he is most looking forward to handing over to somebody else. “The business of art is a whole business, and my profession is painting,” he said firmly. “And I’m very connected with my paintings. I almost don’t want to be in the gallery. It’s like having someone discuss your children.”

The paintings-as-children metaphor extends to process, as well. When Moore is at work, his paintings are never far from his mind. “You go to bed thinking about them. You wake up thinking about them. ‘Should I do this?’ ‘Are they okay?’”

As a child himself, Moore was exposed to the visual arts by his father, an architect, as well as more distant relatives. His great-great grandfather, Nelson Augustus Moore, was a Hudson River School painter, and he grew up visiting homes where the elder Moore’s paintings lined the walls. But far more present in Moore’s daily life was the influence of his mother, an art teacher, who often involved her children in projects around the house. “The bath tub was stained with batik dyes,” Moore remembered, “and she had a photo room upstairs.”

Moore and his brother, Alley, were born in St. Croix, where, after finishing architecture school, their father relocated to start his own firm. (Alley Moore is the art director of this magazine.) “It was like the wild frontier,” Moore said of those years in the Caribbean, in the early 1960s. Although he remembers little of the experience, the call to adventure and an appreciation for design were instilled in him early on.

Throughout high school, Moore explored various artistic media, while also excelling at science, math, and English. Following in his father’s footsteps, he enrolled in architecture school. “The program was just fantastic,” Moore said of his time at the University of Virginia School of Architecture. “I learned the process of design, which kind of underlies painting and pretty much everything. It’s a way of working and thinking and making something from the ground up.”

This comprehensive, nuts-and-bolts approach is one that Moore followed as he transitioned from architecture student to professional painter. It was a gradual shift, and one that took place here on the Island, where Moore has spent almost every summer of his life. Harthaven has been home to Moore and his ancestors dating back to the turn of the century. “That big white house you saw when you drove up was my grandparents’ house,” he said, gesturing down the road toward the imposing, white-columned home that marks the entrance to this tucked-away, Oak Bluffs retreat.

Moore returned to Harthaven between school semesters, living in what had formerly been used as a carriage house, and sold his paintings at the Old Sculpin Gallery in Edgartown.

“I was nineteen or twenty,” he recalled. “That was my summer job. Then I’d go back to architecture school and I was completely into it. It’s a pretty intense education. There’s not a lot of time for much else.”

It wasn’t until after he graduated that Moore entertained the idea of painting full time. He moved back to the Island, living in the carriage house year round, in exchange for caretaking the rest of the property. “It was sort of a great adventure because nobody had spent the winter here,” he said. “It was very rustic. There was only an outdoor shower. You had to drip the pipes all winter long. But I had my studio, my dog, my wave boards. That’s where I spent nine years, being a painter. That was my sole source of income.”

In the beginning, Moore worked almost exclusively in watercolors, which, supported by his background in design, continues to inform his unique process as an oil painter today. “Watercolor is an interesting medium in that the paper allows the whiteness to come out of the painting. You don’t add white on; you paint around the white to bring it out.”

Moore gestured at a painting behind me, a pod of seals sunbathing near the water’s edge, with a spray of ocean rising up around them. “That white foam is the paper.” He pointed to a pattern of miniscule white dots, creating the effect of a wave, mid-crash. “Because the whites are so key to the way the painting resonates, you need to plan the painting out pretty thoroughly. It’s almost like painting oil in watercolor.”

Many landscape painters work from photographs, capturing a moment or scene and bringing it back to the studio to serve as inspiration. Moore does some of this, but also relies on an organic process of growing compositions over time. “I’m fortunate that in different times of year, I’m out and about,” he said, noting that he is particularly inspired while fishing the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass and Bluefish Derby.

He showed me to another painting, this one of a bird – a gannet floating on a long, expanse of ocean, the Gay Head Cliffs looming in the distance. “This gannet I saw off of East Beach. I think it was injured so I was able to motor my boat within feet of it. Later, in October, I was off of the Gay Head Cliffs. It was this gorgeous, undulating sea with very little wind, but that calm swell that shows the ocean is ready for action. And you can see if you look down low there’s a school of tinker mackerel ...” Moore squinted at the bottom corner of the painting. “But this didn’t happen. I didn’t see this. There was no this.”

Later, alone in his boat or back in the studio, he’ll bring the components together to create one cohesive scene. This planning stage is where Moore’s years as an architecture student come into play. “Composition is really important to me,” he said, looking again at the gannet. “The abstract design of the painting. If you squint your eyes and forget that this is a bird …”

Perhaps it is because he invests so much in the structure of his paintings, all before even touching the canvas, that one comment in particular tends to get under his skin. “The one thing I hear a lot, because I’m a representational painter, is: ‘It looks just like a photograph.’ That kills me,” Moore laughed. “I can understand it. It’s usually considered a compliment. But because of all of that work composing it … and for me, a photograph freezes something. Painting has a very soulful, organic base. Even though there are photographs involved – I’m referring to them – it’s a combination of designing, using that information, and then recreating that world.”

Once he has a general idea of how the painting will look, Moore begins the process of readying the canvas, which, like everything else in his method, is a painstakingly thought-out endeavor. “I’m probably as tied to tradition as one can be,” Moore said. “I’m a big believer in craft – how things are made – so these paintings are painted on linen, the sizing is rabbit-skin glue, and then I use a white lead primer.”

Only then does he begin the painting in earnest, first in tonal shades to establish areas of light and dark, and finally by layering in color. The process in its entirety, from inspiration to gallery wall, can take as long as eight months. Most take two to four months. “That’s very different than buying a pre-stretched acrylic canvas and starting right in,” he said.

Much of Moore’s process he developed over time, aided by books and hands-on investigation. “It’s almost like archaeology,” he said. “Trying to figure out how things are made well.” He spent a period of time calling the conservation departments at museums, learning which paintings age well and why. “They’re a great resource,” Moore said. “A lot of those folks work in isolation so they’re happy to chat for a while.”

Adhering to such a time-consuming approach is not without its drawbacks, particularly on a small island. “I painted this whaleboat and I was so excited,” Moore said, nodding at a large painting near the gallery door. “I’d been working on it without really talking about it, and since my paintings take so long to make…last summer I went out and Alison Shaw had a picture of this boat, David Wallis had a painting at the Granary Gallery,” Moore laughed. “I’m sure there were

five others.”

Though Moore insists he could paint the Vineyard forever, whenever the Island feels too small he escapes to coastal Maine, where his mother’s family has a home overlooking Southern Island. Growing up, one of Moore’s artistic influences, Andrew Wyeth, lived nearby. “It was like living near the president,” Moore remembered.

Moore identifies creatively with a group of what he calls “regional realists,” including Wyeth, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins. “Painters that really investigate the worlds that they live in, and are integrated into the lives that they’re leading.”

But after years of studying art history and architecture textbooks, he admitted, “It’s hard to miss the Renaissance guys.” Masters like Michelangelo, Rafael, Leonardo. “These guys could sculpt, draw, build buildings …” he said, admiringly.

Moore continues to be inspired by the community of artists on the Vineyard, though he tends not to talk shop while socializing. “I have some really great friends on the Vineyard, but they’re not painters. I’m so involved in it, at the end of the day the last thing I want to do is talk painting.” He counts Island painters Kib Bramhall and Allen Whiting as kindred spirits, along with the late Stan Murphy. “We’re both kind of isolated artists, so that when we saw each other we felt instantly on the same page.”

Chris Morse, owner of the Granary Gallery and a supporter of Moore’s work since the early years, is looking forward to the chance to reintroduce his friend to the Island in August. “It’s almost like another coming-out party for him,” Morse said. “The response has been interesting in that we have a patronage here that is fairly knowledgeable about Vineyard painters – who have been collecting for twenty-five years – and have never seen or heard of Andrew Moore.”

This, Morse believes, is not due to lack of talent or ambition. When asked how Moore’s work has changed or improved in the time he’s been away from the galleries, Morse said: “It’s hard to say that there’s a scale of improvement when I never remember him as being anything but remarkable.”

Still, Morse hopes that by handing over the duties of representation to somebody else, Moore will free himself up to do more of the work that he loves. “As an artist, if your focus is fractured to promote your work, it takes a great deal of energy. And his work deserves to be

attended to well and professionally. I think it will help him.”

Perhaps this, then, is the beginning of a new chapter for Andrew Moore, one in which his work is available to a broader audience. Back in his home gallery, I imagined the space changed into the productive chaos of a working studio, and asked Moore if he thought being represented elsewhere might have any impact on his work or process.

Ever the traditionalist, Moore offered a sheepish smile and shook his head. “I won’t really be changing much,” he predicted. “But it’ll be fun.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)