On a warm summer day in 1895, a Cottage City Street Railway motorman kicked off the air brake and notched out the controller on his open-air trolley, drawing five hundred volts from the recently strung overhead wires. With a “ting-ting” of his pedal-activated bell to warn pedestrians and carriage drivers, and the swelling whine of traction motors underfoot, he launched the trolley era on Martha’s Vineyard. In doing so, he also effectively consigned to history the horse-drawn streetcars that had rumbled along Island streets for twenty-two years.

Though reproduced photos of the little steam train that ran from 1874 to 1895 between Cottage City and Edgartown are common enough, who knew there were once streetcars here? Not I, at any rate. But horse-drawn streetcars were first introduced to the Vineyard in 1873, and their electric counterparts persisted until 1918, more than two decades after the steam railway’s demise.

Now, 120 years after that first electric trolley clang-clang-clanged across Cottage City (which became Oak Bluffs in 1907), Scott Dario’s Martha’s Vineyard Sightseeing has introduced nearly hour-long down-Island “trolley tours.” These new rigs aren’t really trolleys, of course, but twenty-six-passenger buses designed to look like the streetcars of yore. (Strictly speaking, a trolley is a streetcar that uses a “trolley pole” to draw electricity from an overhead wire: a horsecar is a streetcar, in other words, but not a trolley.) But with their nostalgic appearance and windows that open to let in sea breezes, they provide a good ride and a reminder that the trolley aesthetic still has the power to attract. Not only that, they provide the perfect opportunity to look back at the long-vanished real thing.

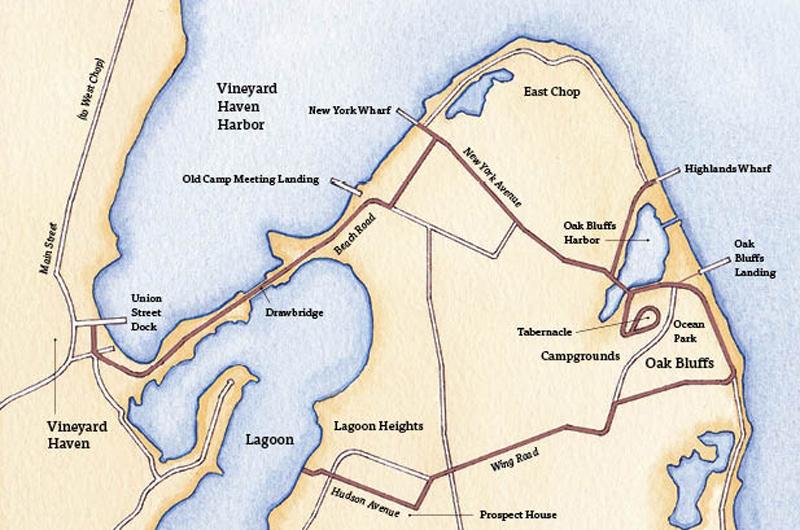

Rails Across Martha’s Vineyard: Steam Narrow Gauge and Trolley Lines, Herman Page’s fine monograph, is the place to start. As is so often the case in Oak Bluffs, the story of streetcars began with the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association, the Methodist summer retreat established in 1835 in Wesleyan Grove. The earliest worshippers got there by making the long trek from the Camp Ground’s original steamboat landing, at the foot of Eastville Avenue, near the bend in the road by the present-day Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. Much closer was the landing at the location of the current Oak Bluffs Steamship Authority dock, which was built in 1867 by the Oak Bluffs Land and Wharf Company, developers of the decidedly secular side of the growing resort town. The principals of the Land and Wharf Company were mostly Islanders who were respectful of the Camp Meeting Association, but the Methodists nonetheless worried about the honky-tonk atmosphere of Circuit Avenue and Cottage City’s potential encroachment on their devout enclave. At one point they even erected a seven-foot-tall picket fence around the Camp Ground; gates opened in the morning and closed at 10 p.m.

It was this moral concern that led to construction of a third docking facility, the Highland Wharf, adjacent to the East Chop Beach Club’s current location. It was built in 1871 by Camp Meeting Association members who bought land in the Vineyard Highlands, near East Chop, against the possibility that the association would choose to expand, or even move entirely to distance itself from the sinners of Circuit Avenue. That never happened, but the new wharf became the official landing for the association, allowing the faithful to circumvent morally hazardous Oak Bluffs.

It was still a bit of a trek to the Camp Ground, however, and the tracks of the Island’s first streetcar line – a horse-drawn, standard-gauge operation called the Oak Bluffs Street Railway – began right on the pier and continued down East Chop Drive. The line veered east across the bridge – later a causeway – between Sunset Lake and Lake Anthony. (The latter lake was opened to Nantucket Sound to create Oak Bluffs harbor around 1900.) Camp Meeting attendees called this ritualistic passage on what was then Kedron Avenue “crossing the Jordan,” and the original line turned right onto Dukes County Avenue, passing the row of cottages that remain today, before angling into the Camp Ground on Siloam Avenue.

From there it looped clockwise around Trinity Park, which at that time was anchored not by the familiar Tabernacle of today but by a huge canvas tent, under which 4,000 worshippers could be seated. When construction began on the “Iron Tabernacle” in 1879, the mile-long line carried small metal and wood parts that had been ferried from the railhead at Woods Hole to the site.

No doubt the most famous passenger to ride this first line was President Ulysses S. Grant, who in August 1874 rode a festooned car behind six horses into the Camp Ground to stay with Bishop Gilbert Haven at his cottage on Clinton Avenue. Grant and his retinue, which included his wife, had arrived at Highland Wharf aboard the steamer River Queen, once President Lincoln’s private yacht but by then in Vineyard service.

All that’s left of this first streetcar line – or any of the lines, for that matter – is a pair of iron rails in front of the headquarters of the Camp Meeting Association. These may be original, or they may have been placed there after the fact to memorialize the horsecars. Opinion is divided.

Meanwhile, Cottage City’s secular side grew as fast as the Camp Ground and the Oak Bluffs Street Railway quickly expanded to serve this clientele with a line that diverged from the Trinity Park route where today New York, Dukes County, and Lake Avenues meet to follow Lake Anthony into the heart of bustling Cottage City. At this junction the conductor, the second member of the crew in addition to the driver, climbed down and used a long-handled tool called a “switch iron” to align the track for either the Camp Ground or the route into the commercial area. Once he was back aboard, the driver stirred his two-horse team into motion and the car rumbled on at a stately pace, not too much faster than a person could walk. Or, for that matter, than a person can drive the same route 140 years later on some August days.

Just past what is now Oak Bluffs harbor is the sole remaining structure built for Vineyard streetcar service. Then a waiting station, it now houses Big Dipper Ice Cream and Cafe. The horses walked on, past the grand Sea View House, which opened in 1872 (and burned in 1892) across from the current steamship landing. Then along Ocean Park with its bandstand, looking much as it does today. Breezes from Nantucket Sound provided natural air-conditioning for passengers, since most of the cars were open, with crosswise bench seating. To collect tickets, the conductor swung along the horizontal running boards, a damp job when squalls blew in.

At Waban Park the route veered south, continuing on Nashawena Avenue, headed for the Lagoon Pond and Prospect House, a grand mansard-roofed Victorian built in the early 1870s in Lagoon Heights. This hotel later advertised itself as “first-class in every respect” with the “finest location on the island,” and “street cars direct to the hotel.” The approximately three-mile ride cost five cents, but Prospect House burned in 1898, decimating the traffic base for the streetcars, and the line was abandoned beyond Waban Park in 1912. A shorter loop was created by extending the Camp Ground line to the park. Long before this, however, the street railways of Martha’s Vineyard had been transformed.

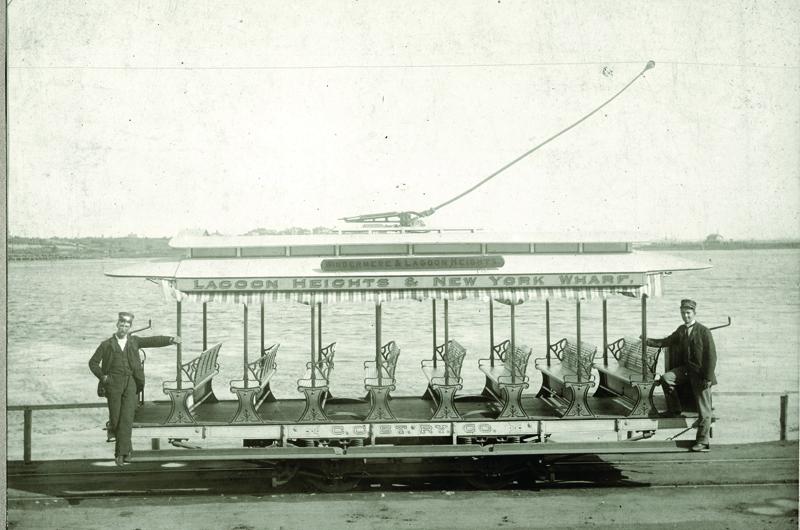

Nationally, the trolley era began in 1887, when Frank Sprague successfully electrified the Richmond Union Passenger Railway Company in Virginia. Cities around the country quickly got the bug, and trolley mania hit the Vineyard in 1892 when the Dukes County Street Railway Company was formed to build an electrified line from Cottage City through Vineyard Haven, West Tisbury, and Chilmark to Gay Head. This dream remained just that and nothing more, but in 1895 wires were strung over the Cottage City Street Railway, which had opened a horsecar line to New York Wharf in 1892, to serve the New York & Portland Steamship Company. The connection to the New York Wharf, at the end of present-day New York Avenue on the Oak Bluffs side of Vineyard Haven harbor, incidentally, led part of Kedron Avenue to be renamed.

From the wharf, the line eventually continued to the Oak Bluffs side of the drawbridge across the opening to the Lagoon. The bridge wasn’t robust enough to support the weight of a streetcar, but starting in 1897 the Martha’s Vineyard Street Railway ran a one-and-a-half mile line between the Vineyard Haven side of the bridge and the Union Street Dock, near where Steamship Authority boats land today. Later, the bridge was rebuilt, allowing trolleys to pass over it.

The Vineyard would remain a trolley Island until 1918, when the wires came down and the tracks were torn up. By that time newly arrived rubber-tired, gasoline-powered jitneys were

charging half the fare of the trolleys and generally traveling faster. The streetcars were, of course, more environmentally friendly, but no one was thinking of that back then.

Today, no trace remains of the Martha’s Vineyard Street Railway: the lunchroom at the corner of Union and Water Streets that served as the Vineyard Haven trolley stop, a power plant, and two trolley barns east of town center are all gone as if they’d never existed. The same is nearly true of the Cottage City Street Railway infrastructure – Highland Wharf and the car barn located near there, and the original power plant where Eastville Avenue meets Beach Road have vanished. The rails were sent off-Island for scrap, to a foundry in Chester, Pennsylvania. Perhaps ironically, perhaps appropriately, they traveled to the mainland in the wooden hull of Captain Zeb Tilton’s venerable Alice S. Wentworth. Built in 1863, this schooner was a decade older than its cargo and had nearly half a century of productive life under sail ahead when she fulfilled this melancholy commission.

So only the building in downtown Oak Bluffs that once served as a waiting station – and, the rails in the Camp Ground, whether authentic or not – survive as tangible reminders of how down-Island Vineyard residents and visitors got around in the time of the trolley. Those and, of course, the ersatz “trolleys” set to appear this summer.

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)