The old barn at Nip’n’Tuck Farm sits centered on a hilltop overlooking State Road in West Tisbury like a fading castle. The shingles are worn, there is missing glass where windows used to be, and holes too far gone to patch. The family farmhouse next to it is tired too, but looks down to sweeping green pastures surrounded by forest. At the end of the driveway stands the dairy store that used to house coolers full of fresh raw and pasteurized milk. Across the field a small mountain of firewood waits for cooler days, keeping company with tractors, trucks of various ages, and a pair of prized chestnut draft horses fenced in with tangled barbed wire.

Fred Fisher Jr. runs the farm he grew up on. Now in his late fifties, standing tall and lean, Freddy, as he is called, bears little resemblance to his round and gregarious father, Fred S. Fisher Sr., who ran the farm until his death in 1998. Freddy’s whole life has been the farm, and like his parents, he and his wife Betsy have raised their family here. As it was with his parents, Nip’n’Tuck has been a complicated blessing. In a day when local agriculture is widely venerated and small farmers are coming back into fashion, at this most iconic up-Island homestead family farming is something between a labor of love and a life sentence.

In 1955, Fred Sr. and his wife Muriel had outgrown their modest homestead on Lambert’s Cove Road, a small house and a six-stall cow barn that they had built on about an acre of land. At the same time over on State Road, the Brown family was raising a few cows on their much bigger place called Willow Bank Farm, but was ready to sell. It was down to the wire whether the Fishers could afford to purchase the larger farm, so when the financing came through and the transfer was made, they renamed the place Nip’n’Tuck. The following year they moved their two-year-old daughter Sandra and two-week-old son Freddy to what was then 135 acres of sprawling farmland and forest.

At that time all milk on the Island was locally produced, and the Fishers and other Vineyard dairy farmers sold their product to the Martha’s Vineyard Cooperative Dairy at Cow Bay at the Bend in the Road in Edgartown. Every morning they left the large metal jugs of fresh milk on a platform at the end of the driveway to be picked up by a truck for bottling and distribution. When the co-op stopped buying local milk in 1963 and eventually closed entirely – a result, in Freddy’s opinion, of government regulations – most Island farmers left the dairy business. Eventually only Nip’n’Tuck remained.

Times were difficult, but the Fishers built their own dairy store at the end of their driveway so that Freddy’s mother could deliver milk six days a week. Using the family station wagon at first, and then a pickup truck with a white wooden roof to stave off the heat, she made down-Island deliveries on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and up-Island deliveries on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. The family also shipped milk by ferry to Nantucket, using heavy insulated blankets to keep the milk cool. At peak production, they had twenty-two milking cows, which meant a herd of up to forty cattle with calves and young cattle.

It added up to a farm full of mouths to feed. Nip’n’Tuck also grew vegetables, including a decent sized crop of corn in their fields. They sold corn on the cob at their dairy store, and sickled two bunches of the cornstalks per day to supplement the expensive grain and Canadian hay

for the cattle. Eventually, though, constant battles with corn worms meant the Fishers had to decide whether to spray the crop with pesticides. The family decided to drop the crop rather than spray with poison.

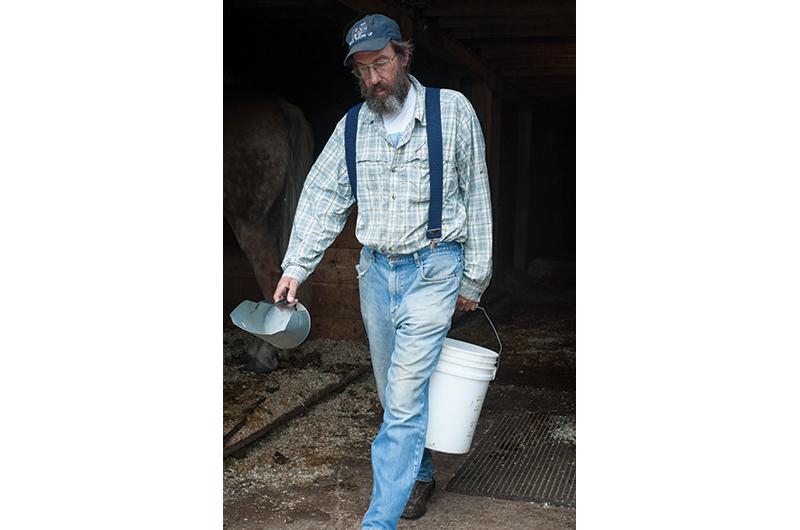

“It was hard,” Freddy said not long ago as he poured water into a bucket for a pair of young beef cattle munching hay. We walked back into the barn and he began cleaning a horse stall. “My father began selling land off almost from the start for as little as two hundred dollars an acre.”

“This is how my father lost my mother,” he said between shovelfuls of manure and straw. “My mother used to say my father was putting money in one end of the cow and it was coming out another end as something else.”

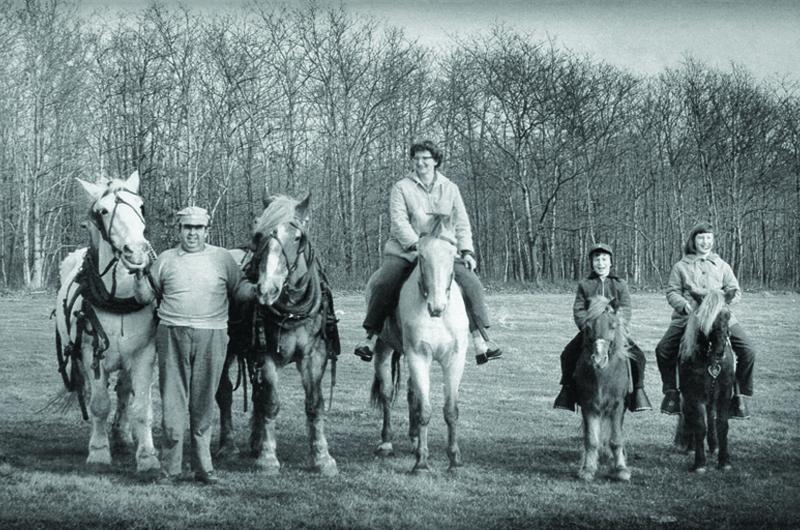

By the late 1970s the financial strain had fractured the marriage completely. Muriel moved back to their old home on Lambert’s Cove Road, which they owned outright. Fred, however, stayed at Nip’n’Tuck and never lost his love of agriculture. Not born into a farming family, he had chosen the life early on, spending summers working at Tashmoo Farm in his youth. In his prime he was almost the living symbol of the Vineyard agricultural scene, serving as both as the chairman of the West Tisbury selectmen and the president of the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society.

“I think he loved our fair as much as he loved farming,” said Eleanor Neubert, the daughter of the late farmer Arnold Fischer of Flat Point Farm and the current wizard behind organizing the annual Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Fair. In particular, Fred Sr. was a patron of the horse pull. For many years before the new Agricultural Hall was built, the draft horse community who traveled from around New England to compete in the horse pull were welcomed at Nip’n’Tuck with a place to park their campers and horse trailers and a feast of kale soup before the pull.

As much as Fred Sr. loved the life he created, it was always a struggle. “We’ve always lived beyond our income,” he told the writer Nancy Safford in 1973, “but I believe you’re entitled to a little fun.” By the time he succumbed to a variety of health issues in 1998, there were only two cows left to milk and debt to pay. According to his son Freddy, the original 135 acres was down to 70.

Freddy had long ago inherited his father’s love for, and talent with, horses. Now he also had primary responsibility for the family farm and its bills to look after. By that time he and his wife Betsy were raising their three children in a house they had built in the back woods of the farm property. To supplement the fifty dollars a week his father was able to pay him to work the farm, he drove a truck, sold firewood, and harvested oysters. He also picked up some cash doing carriage rides for weddings, family reunions, and such, though that was never a moneymaker once you factored in the insurance, license, and cost of keeping the draft horse team fed and shoed.

Today there are no milk cows at the farm, though Freddy keeps four to five beef cattle going and is looking at bringing in some additional Angus. He also has laying hens and pigs. To make ends meet he continues to drive a dump truck, sell and deliver firewood, transport livestock off- and on-Island, and drive his teams of horses. Another small source of income for the farm has been the dairy store at the end of the driveway, though until recently it was in a state of flux. It was an art gallery for a few seasons. Farm stands came and went, including one run by Freddy’s daughter, Prudence.

Two years ago a new sign appeared on State Road near the little building from which Freddy’s mother once made her milk delivery rounds. It reads “Ghost Island Farm,” with an image of an upside-down Martha’s Vineyard island shape that looks remarkably like a ghost in a sheet. It represents not only the wry humor of the new farm’s proprietor, but also something of a serendipitous intersection between two worlds of Island agriculture: a lifelong farmer with an inherited farm, and a man who chose to be a farmer with no land of his own on which to raise crops or livestock.

In late winter of 1989 Rusty Gordon, then nineteen, moved to the Island from Lowell, Massachusetts. He had no plans; he just wanted to come to the Vineyard. With no experience or history in farming, he took a job with Andrew Woodruff at Whippoorwill Farm, and over the next two decades working the land he became a full-fledged farmer. As Whippoorwill Farm grew, so did Rusty’s knowledge and responsibilities, until he was Woodruff’s right-hand partner and a constant face at the West Tisbury Farmers Market.

By 2010 Rusty had come to a point in his work where he wanted to move on. As he puts it, “I needed to start doing things my way and see if I could do it on my own.”

But with the price of real estate on the Vineyard, purchasing land was not an option. He spoke to Freddy about renting the land around the dairy store, but at that time it was unavailable. He also made a serious bid for a long-term lease at Tea Lane Farm in Chilmark. That land, on Middle Road, was purchased by the town of Chilmark and the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank with the plan to turn it back into a working farm. Rusty was one of the final three candidates, but ultimately the farm was awarded by the Chilmark selectmen and land bank advisory board to flower grower Krishana Collins.

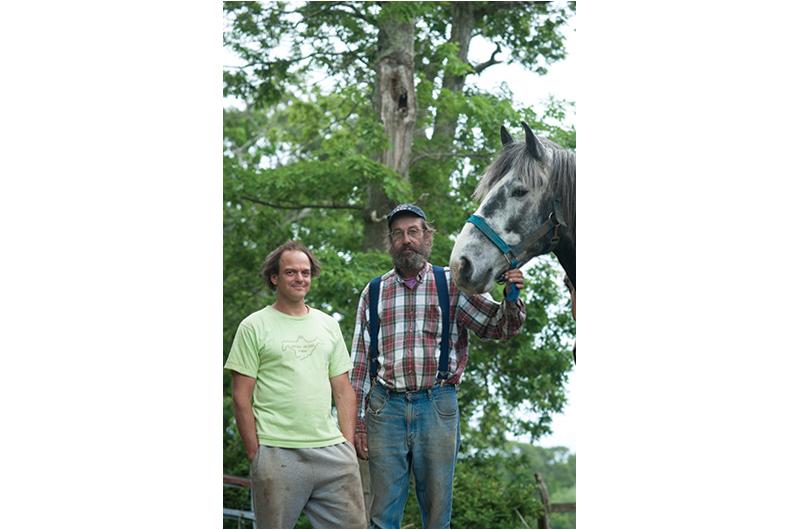

As luck would have it, however, Freddy circled back to Rusty and told him he was now looking for someone to rent the dairy and two acres of the surrounding garden land. It wasn’t exactly what Rusty thought he was seeking, but it was pretty close.

“I was looking for land, not a farm stand. I wanted to focus on growing, not store keeping,” Rusty recalled. “But Freddy was so generous and supportive, offering two acres to farm on and the dairy store to sell out of.”

This year is Ghost Island Farm’s third season at the old Fisher dairy, and Rusty is starting to feel some momentum. He is quick to mention that Cronig’s Market has been helpful in building the brand, and at the farm itself the co-op, which members pay $250 or $500 to join, has been growing each year. Unlike some co-ops, there are no scheduled pick-up times. Members receive a 10 percent discount and free pick-your-own flowers, and can shop any time the farm stand is open. The prices are taken off the fee.

Rusty’s signature crops are his varieties of kale, his salad mix, and tomatoes. All are grown from non-GMO and non-treated seeds, and he uses only organic potting soil. “I hesitate to use the word organic because I am not certified,” he said, “but I start clean and never add anything.” What’s more, the unusual partnership between the two farmers also means that Ghost Island shoppers can purchase meat and eggs raised next door at Nip’n’Tuck, making for one-stop shopping.

It’s still a labor of love to make a go of it as a farmer. Like Freddy, Rusty hasn’t quit his other job, which in his case is co-managing the West Tisbury Farmers Market. But when asked if this is sustainable, he didn’t think long before answering.

“If you look around the Island, many have family farms and family means. I started from nothing. But with the surrounding support of Nip’n’Tuck Farm, I think this can be successful.”

Freddy, too, is happy with the new arrangement, saying, “I am not a shopkeeper. My father loved that stuff. He would talk to you all day.” This year Freddy offered up two more acres, giving Ghost Island Farm a total of four acres to farm, and the use of greenhouses. “I was going to use it for hay, but decided to just let Rusty use it.

“In the beginning I was loaning him equipment,” Freddy went on. “Now he loans me his equipment.”

It’s not exactly The Waltons at Nip’n’Tuck and Ghost Island Farm. And it’s not exactly Modern Family. But for now, it seems to be working for both farmers, not to mention putting local food on local tables.

“Freddy has been so good to me,” said Rusty with a smile. “He treats me like a family member.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)