On June 18, 1722, a small group of men from Martha’s Vineyard were out on what should have been a short whaling voyage when they saw a terrible sight approaching their sloop. Thomas Mumford and the rest of the largely Wampanoag crew were accustomed to the usual hazards of bad weather, and were as adept at avoiding the thrashing tails of their terrified prey as anyone in the world. Every voyage was perilous, they knew, and whaling was only becoming more dangerous with every passing year. But while whales and weather were part of the job, pirates were trouble of another order.

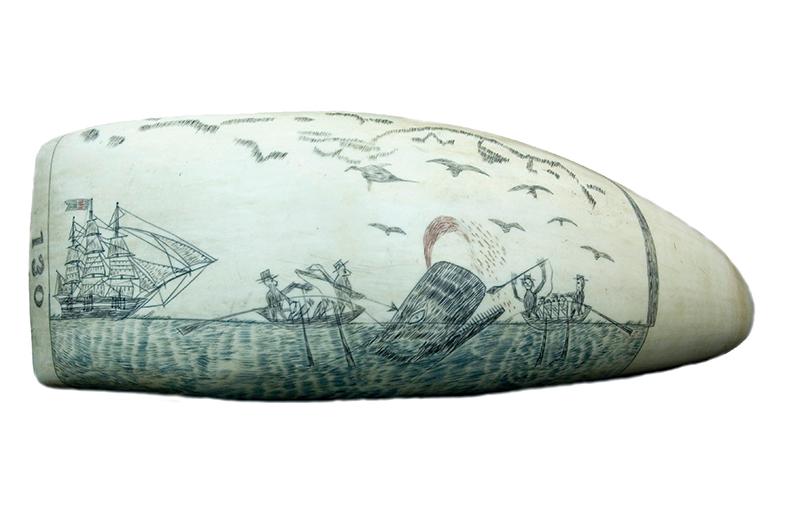

Even before the arrival of Europeans, whales and whaling played a rich role in the Wampanoag culture. By 1702, when Thomas Mumford was born, European settlers had joined the hunt and established an international whale oil trade. At first, crews hunted within sight of land, setting up stations on high points along the shore that faced the open sea. Lookouts scanned the horizon for signs of a spouting right whale – “right” because it floated when dead. As soon as a whale was spotted, teams of about six men hauled long cedar whaleboats from the beach into the surf and, taking up their oars or setting small sails, set out in rapid pursuit. Once killed, the whale was dragged behind the boat back to shore, where it was cut up to harvest the blubber, which was rendered into oil, and stripped of its baleen, the strong but flexible bone found in its upper jaw.

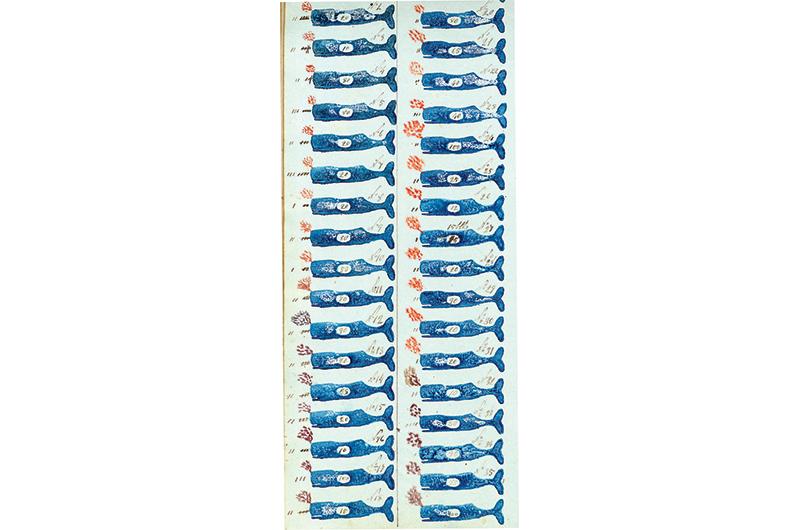

Had Mumford been born even ten years earlier, he might have worked on a shore-based whaling crew. But starting around 1715, crews began pushing farther out to sea, loading several whaleboats onto larger sloops and schooners, and setting sail for points hundreds of miles offshore. This happened not only because hunting had drastically reduced the population of right whales near the Islands but, more important, because whalemen discovered another species, the sperm whale. Smaller than the right whale, the sperm whale produced oil that burned much more cleanly – it could even be burned indoors – and sold for two or three times the price of oil from other species.

In 1722 the Island’s population of about sixteen hundred was nearly evenly divided between Europeans and Wampanoags and, as on Mumford’s sloop, Native Americans often made up at least half of a ship’s crew. Throughout the whaling period, before setting out to sea, whaling captains invariably went to Wampanoag communities looking for men like Mumford. “Ship-owners come to their cottages, making them offers and persuading them to accept them,” said Edward Crandall, who visited the Vineyard in 1807. “Rarely is Gay Head visited for any other purpose.”

The trouble, when it started that June morning, might not have even looked like trouble – just another ship, a two-masted brigantine, on the horizon less than a day’s sail from Edgartown. But the Rebecca, as the brigantine turned out to be, bore down on the small sloop and within an hour the whalemen were no longer hunters but prey. The men waving their cutlasses aboard the Rebecca were pirates, a very real threat in New England waters during Mumford’s lifetime. Pirates routinely tore open the holds of the vessels they captured, pillaging cargo and supplies, and then burned or tossed everything else into the sea. But pirates needed more than gold, silver, food, and supplies to survive. They were always looking for more men, and they regularly abducted new recruits from captured ships.

After a brief stop at Noman’s Land to capture sheep – fresh meat was a rare treat for wanted men – the pirates made their way toward Canada. Somewhere between the Vineyard and the southern tip of Nova Scotia, for reasons that are unknown, two of the other Wampanoag men were hanged, and new details about the attack soon reached the Island. A sea captain “sailing from the Eastward,” wrote Reverend William Homes of Chilmark in his diary, “found the dead body of a man floating upon the water with his head cut off and his hands and feet bound, which act of cruelty is supposed to have been done by the pirates which greatly infest the coast.”The Rebecca, out of Boston, had been captured less than two weeks earlier and was now crowded with close to forty men under the command of a ruthless killer named Edward Low. Low’s crew had recently made three other captures near Block Island, taking food, water, and sails from the vessels and brutally hacking one of the captains with a cutlass. But the attack on Mumford’s whaling sloop was deadlier still. Low’s crew boarded and took a large sail, but they were most interested in the young men working on the crew. They took at least six as captives: two white men and four or five Wampanoags, including Mumford.

A fall, winter, and spring went by on the Vineyard and at sea. Whether by then Thomas Mumford’s family had given up hope of ever seeing him again is impossible to say. For an entire year since his capture, Mumford had been held aboard Low’s ship as it made a sweeping arc across the Atlantic and back, including a five-month swing through the Caribbean. He was forced to serve as a cook for the crew, but otherwise kept to himself. Then, almost a year to the day after he had been captured, Low and his pirate crew returned to the very same spot between Block Island and Martha’s Vineyard, and this time it was the outlaws’ turn for a disastrous day.

By that time, Low was notorious on both sides of the Atlantic for his torture of the men he captured, especially the captains of vessels. One such captain, Thomas Welland of Boston, was hacked repeatedly with a cutlass in early May 1723, with one blow completely slicing off his right ear. He later said he bled on the deck for several hours without help. Other sailors were tortured with fire, searing their flesh to the bone “to make them confess where their money was.” In a particularly brutal attack, Low cut the lips off a Portuguese captain and broiled them over a fire, forcing the bloodied man to watch the spectacle of his own flesh being cooked, before killing all thirty-two men aboard the ship.

Low was “the most noted pirate in America,” wrote Peter Solgard, the captain of the British warship HMS Greyhound, whose job it was to hunt him down. It was barely dawn on June 10, in the faintest light of daybreak, when Solgard first spotted Low’s vessels some fifty miles south of the eastern tip of Long Island. The pirates were now in two sloops: Low was in command of one, armed with ten guns and about seventy men, while Charles Harris was in command of the other, with eight cannons and just under fifty men. Thomas Mumford was aboard Harris’s sloop.

Naval battles in the age of sail played out in slow motion, and it wasn’t until eight o’clock that morning that the ships were within range of one another and the pirates fired the first shots of the battle. The blasting of cannon fire shattered the quiet morning for about an hour before the pirates, unable to take the Greyhound, tried to sail away. There was little wind, however, and even with pirates rowing at oars they could not escape. By three o’clock that afternoon, the Greyhound was back within range of Harris’s sloop and firing again. With his mainsail shot down and at least four of his men dead or near death, Harris surrendered at about five that afternoon.

Low, however, slipped away in the second sloop and headed toward the Vineyard. Some of the men from the Greyhound took control of Harris’s sloop and brought it back to Newport, Rhode Island, with Mumford aboard, while Solgard continued to chase after Low. The Greyhound followed Low’s sloop until about nine that evening, but then gave up. “The night coming on,” Solgard wrote, the men aboard the warship lost sight of the pirates, “believing they had stood in betwixt Rhode Island and Martha’s Vineyard.”

The Greyhound’s historic battle with the pirates was celebrated from Boston to New York, but Mumford wasn’t safe yet. On the afternoon of July 10, 1723, he took the stand and, speaking through an interpreter because he barely spoke English, told the court in Rhode Island that he had been captured by Low’s crew a year earlier and held against his will ever since. This didn’t guarantee his freedom, however, as captive sailors were often convicted if other witnesses testified that they had helped plunder ships. Fortunately for Mumford, another indicted captive corroborated that he “was only as a servant on board,” and had never fired any weapons or taken anything off a captured vessel. Mumford was unanimously acquitted, ending thirteen months of captivity, and made his way home to the Island.

Other Vineyarders were not so lucky. The battle with the Greyhound left Low thirsty for revenge, and the very next vessel the pirates encountered after running away from the warship in June was a whaling sloop under the command of Nathan Skiffe. Skiffe was thirty years old that summer, and while he had recently moved to Nantucket he had strong ties to the Vineyard. His father and grandfather were among the first English landowners in Chilmark. His uncle, Benjamin Skiffe, was also a leading figure in Tisbury and Chilmark as the owner of the fulling mill, a captain of the local militia, and the Island’s representative to the Massachusetts General Court.

Skiffe’s crew of about a dozen men were whaling some eighty miles offshore when Low caught up with them. Boarding the sloop, the pirates immediately singled out Skiffe as the captain. Shouting and cursing, they “cruelly whipped him about the deck,” according to a report by a crew member. Low then raised his cutlass and hacked off both of Skiffe’s ears, one after the other. As Skiffe stood bleeding on the deck he may have begged for mercy, as many of Low’s captives did. Or other whalemen may have pleaded with the pirates, insisting that Skiffe was a fair and decent man, since pirates were more likely to torture captains who mistreated crews. None of that mattered. “After they had wearied themselves of making a game and sport of the poor man,” a survivor recalled, “they told him that because he was a good master, he should have an easy death.”

True to their word, moments later a pirate pointed a pistol squarely at Skiffe and shot him in the head.

Gregory Flemming is the author of At the Point of a Cutlass: The Pirate Capture, Bold Escape, and Lonely Exile of Philip Ashton, published in June 2014 by ForeEdge, an imprint of the University Press of New England.