It was an otherwise quiet Vineyard night – the water calmly lapped the shore, the grasses rustled in a light breeze. But out of the darkness they appeared, a raucous band of brothers, eight all told. They found their spot and got the night going, rocking and rolling at the waterside. There were no noise complaints, and the traces left behind were perceptible only to the keen observer. But little did these eight otters know, their nighttime jaunt was caught on camera in a series of undercover snapshots.

The bachelors are part of the Vineyard’s thriving community of coastal river otters, Lontra canadensis. They rank at the top of the food chain, and the Vineyard landscape is marked by their centuries-old trails and the patches of grass flattened by their grooming habits. Yet these nocturnal creatures are seldom seen by humans. As a result, their population size, the ways humans affect them, and their daily habits and patterns have largely remained a mystery. But that’s beginning to change.

For the past four years, wildlife biologist Luanne Johnson of West Tisbury has been working to shed light on these water-adept relatives of the weasel. Johnson is the director of BiodiversityWorks, a Vineyard nonprofit that aims to conserve biodiversity by studying wildlife and promoting community involvement in research and conservation. In order to establish a baseline documentation of the Island’s coastal river otter population, Johnson and her colleague, Liz Baldwin of Vineyard Haven, have collected images from stationary cameras, dissected samples of scat, and tracked myriad otter trails. It is only the second study of its kind conducted on the Atlantic Coast; the first focused on otters in Newfoundland, Canada.

With fieldwork for the baseline study now complete, the two biologists are in the process of analyzing and reporting on their findings. Learning about otters and their habits will lead to a more sophisticated understanding of the Vineyard’s environment and ponds, Johnson says. And should a similar study be repeated a decade from now, the current work will provide a point of comparison, enabling an analysis of changes in the ecosystem.

“We think of wildlife without borders,” says Johnson. “A river otter doesn’t think about who owns the land; it thinks about habitat and where it wants to sleep and where is a good place to find food.”

Scouting miles of shoreline on conserved lands and private properties led Johnson and Baldwin to nearly 150 latrines, or sites where otters socialize, groom, and leave scents and scat. The animals typically establish latrines close to a body of water in a sandy or grassy area. “The grass is all flattened down from rolling and torn up from making scent mounds,” Baldwin says. “And there’s lots of scat. Sometimes when you are walking you can smell that fishy smell before you come up to it.” Visiting thirty latrines regularly, the two biologists scooped up six hundred scat samples, which they then sterilized and sifted, leaving thousands of fish scales, hundreds of crab claws, and a dozen tiny bones to identify.

“I had no idea fish scales were so fascinating,” says Baldwin. “Each one is like a fingerprint.”

The two biologists and volunteers have been cataloging the specimens to get a picture of the otter’s Island cuisine. Thus far they have determined that otters primarily eat small fish species like mummichog and killifish, as well as crab. They also occasionally feast on larger fish like white perch or even small birds.

Otters typically eat 10 to 15 percent of their body weight each day, and coastal river otters typically weigh from eleven to thirty-four pounds. To survive, Johnson explains, they must be opportunistic eaters: gorging on the easiest catches and conserving their energy. The majority of the fish they eat measure less than five inches. “They don’t eat any keepers,” is how Baldwin puts it. “If it’s a bluefish, it’s a baby bluefish.”

Because, as Johnson explains, “their foraging strategy is getting what they need to survive and what is most available,” the otters’ diet can paint a bigger picture about the health of the Island’s ponds. If abundant fish populations diminish in otter scat, it could mean they are diminishing throughout the entire watershed. As such, whether the species thrives or struggles may be a bellwether for the larger ecosystem.

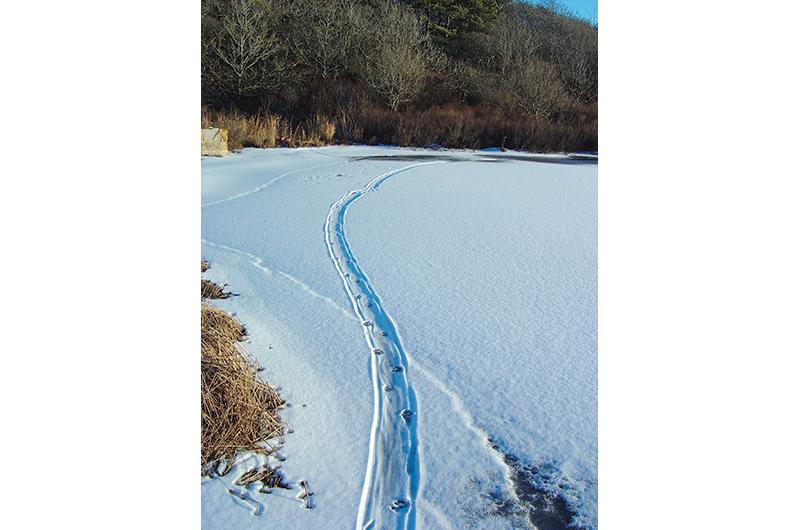

To get from pond to pond, otters traverse ancestral trails, moving as necessary to find food. The distances are surprising. A hungry otter won’t go farther than the nearest good meal, but during the course of a nocturnal hunt they regularly cover around six miles. In challenging situations, on the other hand, they have been known to travel up to twenty-six miles in a night.“Otters will be the first indicators,” says Johnson.

“They crisscross the Vineyard,” says Gus Ben David of Edgartown, a Vineyard naturalist and former director of Massachusetts Audubon’s Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown. “It’s really unbelievable.”

Ben David tracked one route from Farm Pond in Oak Bluffs all the way to Mink Meadows in Vineyard Haven. Luanne and Liz, meanwhile, have tracked another overland route in Vineyard Haven that runs from the Tisbury Water Works through the Tisbury Park and Ride parking lot along the power lines and down to Lagoon Pond.

The otters move quite fast, too. When running or sliding, they can travel up to sixteen miles per hour. “It’s classic,” says Ben David. “They run with a hump in the back – they’re a weasel – and then they slide. They’re like a shrew; they burn vast amounts of energy.”

While Luanne Johnson headed the diet research, Baldwin set up a camera-based project to gather behavioral information. She placed cameras at twenty latrines, from Lobsterville in Aquinnah to Chappaquiddick, hoping to capture data on otter activities, human interference, and abundance of otters at these sites. Her results, collected over more than a year, show that otters are more social than territorial. They spend a large amount of time smelling and investigating scat and scent mounds at the latrines. Unlike coyotes or dogs, which mark their territory as a warning, otters use the latrines as a way to make connections.

“They are spending more time getting a message at a latrine site than leaving a message,” Baldwin explains. The cameras also showed the otters using these sites for grooming – rubbing and rolling around in the latrines’ grass and sand to fluff up and clean off their salty fur. “You know when you go in the ocean and your hair gets crunchy?” she asks. “If their hair isn’t perfectly smooth, it will mess up their thermal regulation.”

Temperature management is important for this aquatic mammal, which continues to swim throughout the year. Their watery winter hunts are made possible by a layer of subcutaneous fat and glands that secrete the waterproofing agent squalene.

It was Baldwin’s camera project that captured the big eight-otter bromance at Black Point Pond in Chilmark. According to both biologists, the size of this congregation suggests that there isn’t currently a high level of competition for food amongst Island otters.

Male otters are known to travel and forage together in bachelor groups, while female otters travel with their pups, typically splitting from their year-old young when they give birth to the next litter. This happens on the Island in late winter or early spring, and occasionally a year-old female will stay with her mother to help with the new litter. Otters mate in the spring, but thanks to a highly unusual biological feature called delayed implantation, female otters don’t begin gestation until the following winter. Implantation occurs – across the species – when the photoperiod reaches ten and a half hours of sunlight per day, says Johnson.

The good news is the camera study didn’t indicate a direct human impact on otters, though Baldwin notes that this may have been because the sites with high human use were not those where she saw the most otter activity. She adds, however, that otters are indirectly affected by humans every day, since our presence affects the water quality of the ponds.

Going forward, the team of Johnson and Baldwin hope to delve deeper into the relationship between otters and humans. They have applied for a grant to fund a project focusing on otter habitats near urban sites in southeastern Massachusetts, while on-Island they plan a more hands-on study that will include marking or microchipping otters to get a clearer picture of population size.

“It’s difficult enough to do a US population census where you can speak to human beings and knock on their doors,” Johnson says. “So imagine trying to do that with wildlife that are nocturnal and aquatic, and all look the same.”

And, it might be added, otters are very, very good at avoiding humans. For the duration of her camera project, Baldwin only saw four otters with her own eyes. “They will run into the water; that’s where they feel most safe,” she says. “They’ll stick out their heads – they are very curious – and watch you, maybe snort at you a little bit.”

Even Gus Ben David, with his decades of work with Vineyard wildlife, still calls it a treat when he spots an otter. “It’s exciting every time you see one,” he says. “No matter how many times, it’s always a beautiful experience. Same with a butterfly, an eagle, a white-tailed deer. You never tire of watching them. It’s art.

”

For more information or to support BiodiversityWorks, visit biodiversityworksmv.org.