When construction of the $48 million Martha’s Vineyard Hospital neared its long-awaited completion in 2010, there was considerable excitement about the Island’s new state-of-the-art health facility. But somewhat unexpectedly, the Island gained much more than a medical institution when the doors opened. The hospital has become the Island’s de facto art museum, housing more than three hundred donated works, and the collection is growing by leaps and bounds. The story of the hospital’s artistic transformation is one of both foresight and imagination.

As work on the building neared completion, hospital board chairman, Tim Sweet, and building committee chairman, Edward Miller, met with architects from Tennessee’s Thomas, Miller & Partners to discuss how to include art in the interior design budget. Institutional construction projects typically include funding for art, but the works tend to be generic, not representative of a community. The two men agreed that decorating the new building’s walls with cookie-cutter, hotel-style art would not do. They understood that this new institution needed to draw on the Island’s own artistic talent if it was to truly reflect the character of the place and its people. While it might not be appropriate for a hospital to spend hard-raised donor money to buy original art for its walls, it certainly could solicit Island artists and collectors to donate work.

“We started talking to a few artists and found an enthusiasm there,” Sweet says. “We were not fully aware of how big a project it was going to be. There are ninety thousand square feet of building, so you can imagine how many walls that is.” He suggests they were blessed by a certain naiveté.

It became obvious early in the process that a separate committee was needed to do the heavy lifting, and Sweet thought Miller was perfect for the job. A former CEO at Schroder Salomon Smith Barney who retired to the Island in 2002, Miller was responsible for acquiring art for the company’s London office, which is located in a building designed by architect and Vineyard summer resident Lord Norman Foster. He saw firsthand the impact of art on employees, clients, and visitors, whose interactions were enhanced even by labeling the works.

When Miller presented to the rest of the hospital’s building committee the idea that the hospital should display only Vineyard-related art and artists, he argued that the goal would be to stimulate viewers. That idea seemed counterintuitive at first. Shouldn’t art in a hospital be soothing rather than engaging, the committee wondered? Miller’s response was, “No. The more interaction between the viewer – patient, family, visitors, staff – and the art, the better. I knew it would work.”

Miller mapped out the ways the permanent art collection was important. First and foremost, art would transform the hospital into a more agreeable, human space and expand its identity as an Island institution. Art could also serve as a valuable part of the patients’ healing process. And the permanent public display of Island art could be a bonus for the artists themselves. They would gain exposure in a public setting, and were likely to put their best work on display. What’s more, the effort had the full support of hospital CEO Tim Walsh from its inception.

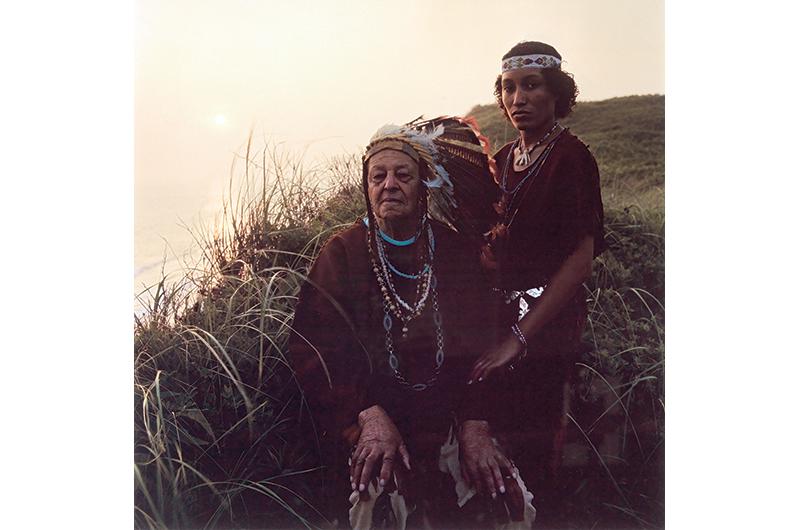

Rules were laid down for the acquisitions process: Except for Miller as chair and contact person, the collection committee members remain anonymous to avoid any pressure or lobbying during the selection process. Additionally, the art has to be connected to the Island, either because the artist lives or has spent time here, or because the subject of the work relates to the Vineyard. Even if someone wanted to donate the Mona Lisa, it wouldn’t qualify, Miller quips. To avoid conflicts of interest, there is no participation by galleries. The committee reserves the long courtyard corridor wall for temporary exhibits, recently displaying vintage photographs from the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

The collections committee proved very effective, reflecting a variety of tastes, according to Miller. “We aren’t trying to be the arbiter of what’s the best art,” he says. Nor can the committee curate in the traditional sense. As Miller points out, it “toils in the shadows on a schedule that is both organized and spur of the moment.”

The hospital’s director of development, Rachel Vanderhoop, was enlisted to keep track of the collection and post it on the hospital website. The website itself quickly became an important component of the collection. It lists all the artists represented, shows the pieces they’ve contributed, where those works are located, and provides links to the artists’ contact information or websites (mvhospital-art.com). A pilot inpatient iPad program, conceptualized by the hospital’s volunteer director Angie Rhoderick, allows patients to easily view the website from their beds and discuss art with visitors and volunteers. Patients can pick out work they’d like to see and, in most cases, go see it. Thus the collection expands beyond what appears in an individual room and encourages patients to get the physical exercise that’s often integral to their recovery.

“I began thinking about other ways the patients could get involved with [the art collection],” says Rhoderick, who also works as a software engineering consultant at IBM. “I did some research on how technology is improving the wellness of patients...and I thought wouldn’t it be wonderful for those who couldn’t get out of their beds to have the opportunity to visit the artwork at the hospital on an iPad.”

A key player in the hospital’s art acquisition has been Miller’s wife, Monina von Opel. Although not trained as a curator, she has long been active in the Island’s arts and culture scene, and this past summer she oversaw a group exhibit of work by nine women, entitled Nine Artists – Thirteen Years, at Featherstone Center for the Arts in Oak Bluffs. Miller calls her the catalyst for many additions.

“For me it’s like Ali Baba’s cave,” von Opel says with enthusiasm. “When I go to people’s houses, I’ve got my eyes on the walls. I’m always snooping around.” She looks through the newspapers, goes to art shows, and relies on word of mouth. When von Opel was traveling in France, a friend gave her the name of an artist in Paris. “Off I went,” she says. As a result, the hospital acquired Woodcutter (in a New Land), an Irving Petlin pastel that hangs in the waiting area for the emergency room.

Another time she visited Gay Head Gallery in Aquinnah. “I walked in and saw this absolutely fabulous photograph of a horse’s backside by Barbara Norfleet. It turns out the Museum of Modern Art [MOMA] in New York City has a copy of this photo.” The hospital’s print now hangs in the first floor elevator lobby.

Like her husband, von Opel has a taste for bricolage. “I like to mix things,” she says. “It’s the way I see the world.” She is not bothered by the fact that some people have reacted negatively to some of the work. “We say, ‘That’s fine. If you looked at it in a museum, you might not like it either.’ It sharpens the eye; it stretches you.

She helps Vanderhoop mount the labels for newly hung art and advises on the placement of artwork. Labels are just one of the ancillary expenses for the hospital’s art collection, others include mats, lighting, digital images for the website, framing and special hardware, as well as installation. Miller consulted with the MOMA on the security needs of an art collection that’s housed in a building with twenty-four hour access and no admissions fee. “We all end up in that place, whether it’s from tick disease or falling off your bike,” says von Opel.

The twenty-one inpatient rooms were among the first to acquire art. Most display photographs by Alison Shaw and Janet Woodcock, early contributors to the hospital. Impressed by the local art she saw displayed at a hospital in Brunswick, Maine, Shaw contacted the hospital before the permanent collection was even established.

“She opened up her whole portfolio,” Sweet says. Art advisors for a number of hospitals, including Boston’s Beth Israel and Massachusetts General, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, and St. Mary Medical Center in Evansville, Indiana, have contacted Shaw over the years, so the idea of placing her images in a hospital was not new.

“My work is pleasant and pretty to look at,” she says, adding that in her opinion work in such a site should be soothing and calming, not ominous, angular, or red. “The new hospital was an ideal backdrop, because I found the inside drab and uninteresting, overly large. If the inside were colorful or textured, the art might clash with it.”

Another early contributor was painter Rez Williams of West Tisbury, 2013 recipient of the Creative Living Award presented by the Permanent Endowment Fund for Martha’s Vineyard. “For years I’ve been turning over in my mind some kind of space for Vineyard art,” he says.

Williams praised the choice of Miller and von Opel as overseers of the hospital’s acquisitions. “They’re exactly the kind of people to curate such a collection,” he says. “They had an eye and could discriminate, yet have been open to everyone. You had to have somebody who really knows about art beyond the shores of the Vineyard.” Williams was shown the space proposed for one of his large boat portraits and instantly thought, “Boom.” He painted My Way to go in the hospital’s courtyard corridor.

“There were some minor criticisms of the subject matter,” he says. A cartoon figure of Frank Sinatra appears on the bow of the New Bedford fishing boat named after the singer. Williams explains that the company that owns the vessel buys and refurbishes boats. Since it’s bad luck to change a boat’s name, they stuck with the original, and the cartoon Sinatra is part of their livery. Williams was pleased to see a portrait of Bob Dylan – one of many celebrity portraits by photographer Guy Webster – hanging near his painting. With seventy-seven pieces on display, Webster, who summers in Menemsha, has the most work in the hospital, much of it populating the hallways near the laboratory and the radiology offices.

Some artists are willing to create and donate a commissioned piece specifically for the hospital collection. When von Opel asked West Tisbury artist Susan Copen Oken to donate a painting from her Sunflower series, the artist didn’t want to give up the specific one von Opel asked for. Instead, she created a new version of the work, now on display in the second floor lobby.

Painter Allen Whiting of West Tisbury was happy to be included in the permanent collection. “I didn’t have a lot of money to give to the building campaign at the time, so this was the way we did it,” he says.

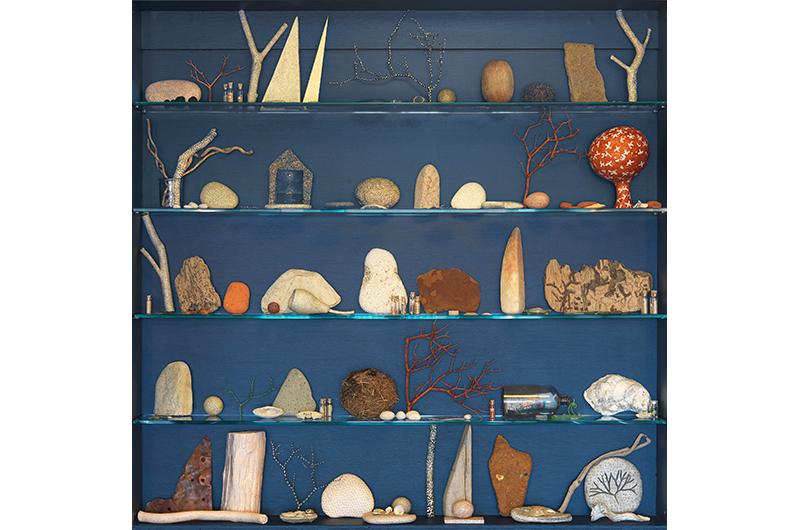

Having a hospital double as an art museum is hardly problem-free. Because the building’s lighting design was executed before the advent of the collection, much of the work is not yet adequately lit. Vineyard at Sea, the large and spectacular mural by Edgartown’s Margot Datz, is installed in the woefully small conference room off the main lobby, where it is not easy to view. The hospital is also tasked with finding the appropriate method for cleaning the art, especially crucial in a building that needs to be as sterile as possible. Some art will always be relatively – if not entirely – off limits for public viewing. And the hospital is limited in the kinds of three-dimensional work it can accommodate.

At present, the collection consists primarily of work donated by living artists. Collectors have yet to come forward with gifts of past Island masters such as Thomas Hart Benton or Stan Murphy, but that doesn’t mean they can’t and won’t. Meanwhile, there are plenty of Island-related artists who are not yet represented, and at ninety thousand square feet, the hospital has plenty of wall space left to fill.