In 1995, after five years as a farmhand at Pimpneymouse Farm, musician Kevin Keady left because, as he says, “I didn’t think Chappy was a place I’d want to stay.” One winter spent living off-Island convinced him differently, and he’s been back ever since, writing songs, performing, and working on the farm. Twice a year he hosts a gathering around his campfire with songs and stories. He goes off-Chappy to perform with his band, Cattle Drivers, at the West Tisbury Farmers Market. By Kevin’s definition, he has a life of luxury in the privacy of his little camp, a former hunting shack, where it’s basically him and the wildlife. When he’s not running the tractor, he swims, grills, and relaxes in sweat lodges. He says, “You’d have to be silly not to stay here as long as you could.”

On summer mornings Nefititi Jette drives from her home in Aquinnah to open the Chappy Store. Then she heads back up-Island to her full-time job as an accountant for the Wampanoag Tribe, of which she’s a member. Often her daughter Rachaya stays to mind the store, which belongs to Nefititi’s grand-father, Gerry Jeffers. Gerry is one of the last Wampanoags to grow up on Chappaquiddick, in the 1940s and ’50s, when there were only about four families in the winter. His mother, aunt, and grandmother ran the popular, but now closed, Chappaquiddick Outlook Restaurant on the shores of Cape Pogue, serving food they grew on the family farm

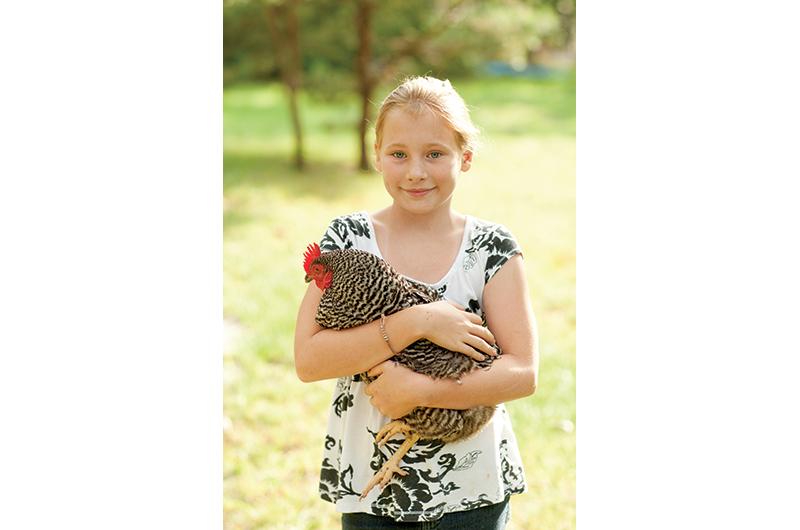

Gabby McElhinney Wilbur, daughter of Shelley Wilbur and Jack McElhinney, has the poise and thoughtful manner of someone much older than her twelve years. She has her own pet-sitting business and keeps a flock of chickens. Until recently, she was a homeschooler who studied subjects ranging from Egyptology to container gardening. Last year she entered the sixth grade at Edgartown School, where she enjoys art, sports, and playing the saxophone. She says seeing people at school gives more balance to the quiet life on Chappy.

Lucille Gostenhofer met her husband, George, in 1949 when she sailed to the Island with him and two other male engineering students, causing George’s Edgartown uncle to warn him against loose women. Lucille’s confident, no-nonsense, welcoming manner belies her inability to see – the result of eyesight deterioration that began as a young woman. Despite vision problems, Lucille supervised their six kids at the beach, in their sailboat, and on the family pony. She would serve up meals at a picnic table that filled half the kitchen. Last year she and George celebrated sixty-one years of marriage and fifty years in the summer house they built overlooking Katama Bay.

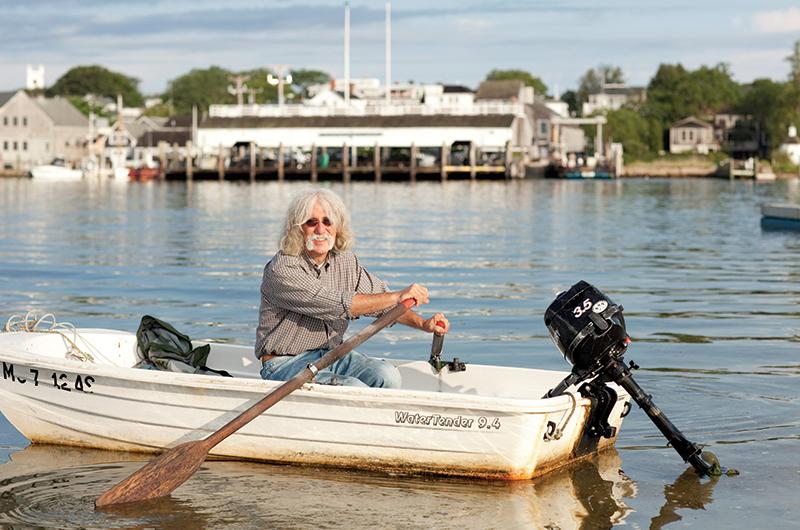

For eight years Dennis Goldin, an internist and rheumatologist, has commuted to Quincy four days a week from the house he shares with his wife, attorney Nancy Slate. He likes Chappy’s sense of community – “an eclectic group of very intelligent people” – and the challenge of living on an island. On commuting days, he leaves the Chappy Point in his dinghy at 4:30 a.m. all year long. One winter morning he found himself mid-harbor with a dead motor. As he blew back toward Chappy, the motor became wedged in the sand in water deeper than his boots. By the time he rescued the boat and his computer, his hands were too cold to open his car door – but he still got to work that day. His regular route takes him to Dippin’ Donuts in Edgartown (where they have his coffee and cruller ready), the 6 a.m. ferry in Vineyard Haven, and then an hour’s drive to his office. “When I come back at night, it’s completely dark. I look up at the starry sky, with no one else out there. It’s an uplifting experience every time I do it.”

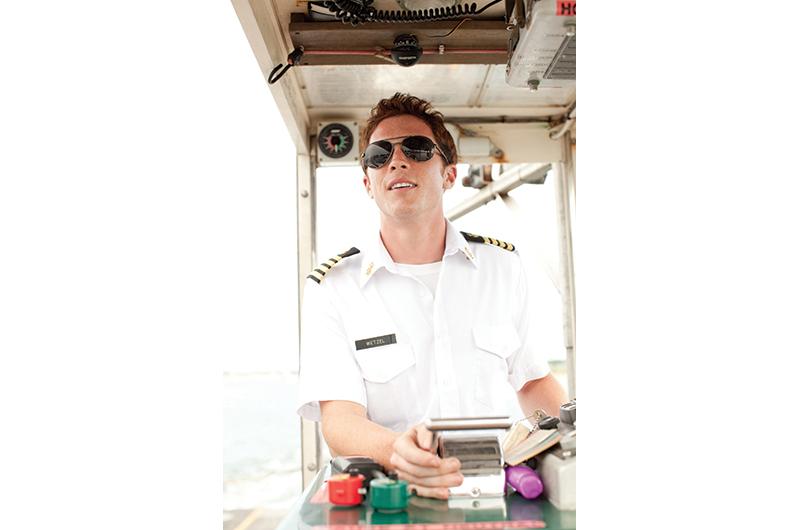

Matt Wetzel started as a seasonal deckhand on the Chappy ferry when he was fourteen. He liked getting to know the local residents, and being known by them. He would wear Tshirts with Wetzel written on the back, until fellow workers kidded him about only having one shirt. When he added I, II, and III to the shirts, people thought he was Matt Junior or Matt the third. Once he got his captain’s license, he started wearing a white shirt with epaulets, “to add professionalism to the job.” Matt, who hails from New Jersey, appreciates Chappy’s peacefulness. In his off time, he likes to loaf and watch videos, and last year he took up skeet shooting. Matt recently graduated from Union College, and plans to take over his parents’ pharmaceutical research company someday.

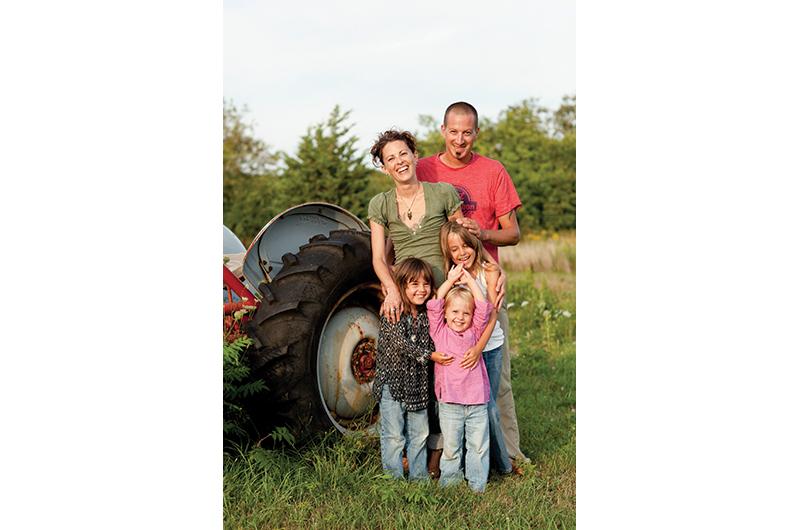

Tina Humber-Floyd’s dream is for Tom’s Neck Farm to be a working farm again. As a kid she used to visit the farm with her dad when it was a hunting club, and as a student at Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School she met her husband, Colin Floyd, whose family has owned the farm for more than eight generations. Their future house, moved across several fields from a neighboring lot, sits on blocks behind the chicken coop, awaiting a foundation. Tina tells their three girls (ages four to eight) how lucky they are to live on Chappy. “It has a great community, beautiful land, and wildlife everywhere. There’s no other place like it in the world.” She’d like to see Chappy return to the days when everyone had a vegetable garden and chickens. She’d like a goat to milk too, and says, “One of these days, I won’t ever have to leave.”

Susie Lindenberg spends summers with her family in an old-style Vineyard cottage at a location remote even for Chappaquiddickers, near the lighthouse out on the neck of Cape Pogue, accessible only by boat or four-wheel-drive vehicle. The fifteen-minute drive on the sand road along the pond – often three round trips a day – gives Susie a chance to watch osprey and remember the feeling she had when they bought the house eight years ago: “We’re the luckiest people in the world!” Solar electricity, no television, and a view of beach grass, sand, and water are a welcome contrast to their Darien, Connecticut, lives. The biggest problem with living so far from civilization? “Ice,” says Susie. “And ice cream!”