Thirty years ago, the ferry Islander carried me to the Vineyard on my first visit, and on that crossing we met the Naushon, steaming toward Woods Hole. Both boats are gone now, of course, as are two other ferries that served the Vineyard and Nantucket back in those days – the Uncatena and Schamonchi. The ferries have always been the Island’s lifeline, and their particularities stay with us – in historical documents, in photographs, and in our memories – even after the boats sail away for good. However, most of those vessels themselves now are lost, gone to scrap or headed that way.

The workhorse Islander, a gritty, seemingly indestructible vessel built in 1950 in Baltimore by Maryland Drydock Company, came to be a constant in my Vineyard experience. The Islander was the first drive-through boat built for Vineyard service and the first that could carry trailer trucks – a huge change in the way freight would be delivered to the Island in the years to come. Not only that, it could hold nearly twice as many automobiles as its most recent predecessors. As the longest- serving boat in Vineyard history, the Islander achieved an illusion of permanence that caused its retirement in March 2007 to be particularly wrenching. I made my last crossing in her stalwart hull with nostalgia and special regret.

Almost immediately, however, sorrow turned to elation. Not only did the Islander appear to have a future, but that future would be in my other home waters – New York harbor. In August of that year, the Governors Island Preservation and Education Corporation (GIPEC) paid $500,000 for the Islander to ply the eight hundred yards from Manhattan’s Battery Maritime Building to the Soissons Dock on Governors Island – a run that could be considered semi-retirement after the Islander’s more than half a century of shuttling the seven miles from Woods Hole to the Vineyard and occasionally even farther, to Nantucket.

By the end of the year, the vessel was berthed at Governors Island’s Yankee Pier; it was a humble companion to the Queen Mary 2 and other mammoth cruise ships that dock just across Buttermilk Channel. The corporation hoped to use the vessel to help handle the growing crowds that were making a day trip to the spacious grounds and historic buildings of the island, managed by the National Park Service.

In an interesting aside, a Governors Island ferry – named, appropriately, the Governor – came to the Vineyard for the 1998 summer season and remains here today as a freight boat. An open-deck vessel, it was built in 1954 for West Coast service between San Diego and Coronado, and later served the Washington State Ferries. The Governor was then acquired by the U.S. government and placed in Governors Island service, before moving on to the Vineyard, where it has served well these past twelve years.

Sadly, the same cannot be said about the Islander at its new island. Early in 2009, hopes for the Islander’s return to service were dashed and a wealth of recriminations ensued. Engineers were able to give the boat the kind of inspection that (according to GIPEC) time pressure had prohibited before the initial auction. They found it in poor condition and in need of more than $7 million in repairs. GIPEC admitted that the purchase had been a bad idea, and in February 2009 offered the boat for sale on eBay. The winning bid – from Donald Slovak, an upstate New York scrap collector – was $23,600. The boat remained for a time at Yankee Pier, as the Governors Island agency at first wouldn’t release it, claiming the purchaser lacked proper insurance. Earlier this year, however, it was purchased by Donjon Marine Company, headquartered in New Jersey, and moved to Port Newark for scrapping.

Nevertheless, the Islander’s extended stay on Governors Island did give me another occasion to say goodbye to this old friend. In late May last year, I crossed from the Battery – aboard the 1956 ferry Lt. Samuel S. Coursen, another old-timer, one that has spent its entire life in the same service – to visit the Islander, no doubt for the final time. Though one newspaper report had described the vessel as a “useless rusting hulk,” it looked in fairly decent shape to me: slightly rust-spotted, to be sure, but its tapered black band was unmistakable, its gold-on-black name boards still in place, though not for long.

The Islander, of course, is not the only bygone Vineyard boat with a story worth telling. Featured here are five other ferries that served the Island, and all are vessels that – during or following their service to the Island – I’ve encountered personally.

Martha’s Vineyard, built in 1923

The Martha’s Vineyard – launched as the Islander in 1923 at Bath Iron Works in Maine and renamed in 1928 – marked a radical change and dramatic step forward in steamboat service to the Islands. As a steel-hulled, propeller-driven vessel, it was significantly unlike its wooden-hulled, side-wheel predecessors and proved so successful that within five years it would gain two virtually identical sisters, the Nobska and the New Bedford. By the end of the decade, another similar but somewhat more well-endowed sister, the Naushon, would join them.

Curiously, I met Martha’s-Vineyard-the-boat more than a decade before setting foot on Martha’s-Vineyard-the-island. In 1968 I’d gone to Bridgeport, Connecticut, hoping to board the steam-powered Catskill, a 1924 freight-boat-style vessel, and steam across Long Island Sound to Port Jefferson. As it turned out, the Catskill was gone. Instead I encountered the rumble of a diesel boat – a significant disappointment, though the replacement had fetching lines and, no doubt, some history of its own. It was the Martha’s Vineyard, which had swapped its steam plant for diesel in 1959. On subsequent crossings, I’d accord this classic vessel much more reverence.

The Martha’s Vineyard had ended regular service for the Steamship Authority in October 1956 and three years later was sold to Rhode Island Steamship Lines, which made the steam-to-diesel conversion. After summers of intermittent use in Massachusetts waters, the boat was chartered in 1968 and later purchased by the Bridgeport & Port Jefferson Steamboat Company. It remained in service between those port cities until 1985, at which point a preservation group called Friends of Nobska tried to purchase it. (The Friends originally hoped to restore and convert the Nobska to a working steam ferry and museum, but since it was not for sale at the time, they turned their attention to its sister boat, the Martha’s Vineyard.)

Though the Martha’s Vineyard deal came tantalizingly close to completion, it ultimately fell through. The boat was sold instead to the Massachusetts Bay Lines and went to Boston harbor. Plans to convert it for dinner cruises never reached fruition, and it remained docked at the Charlestown Navy Yard. Late one night in 1990, with the tide dropping, the boat’s guard rail snagged the pier and, dangling by its mooring lines, the vessel began to list – and then to take on water. A tug was summoned to help but arrived too late, and the Martha’s Vineyard sank. It was scrapped in situ, a sad ending to a once-promising scenario for the Friends and all lovers of maritime steam.

Nobska, built in 1925

As a newcomer to the Vineyard in 1979 and a longtime aficionado of classic steamboats, I was sorry I’d missed the Nobska, a near-exact copy of the Martha’s Vineyard that was also built by Bath Iron Works. The Nobska had served the Vineyard and Nantucket for close to half a century – an impressive record later surpassed by the Islander – before its 1973 retirement. The following year it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1975 was sold to become a (soon-failed) restaurant in Baltimore.

On the Vineyard, I joined the Friends of Nobska, which was dedicated to bringing it back to the Islands as a living museum to the age of steam. The group hoped to run the Nobska during the summers on a daily round trip between New Bedford and the Vineyard. For the better part of three decades, I alternatively exulted in the dreams and suffered through the defeats of that group (which, as it became more professional, morphed into the New England Steamship Foundation in 1994).

After years of trying (and the failed flirtation with sister boat Martha’s Vineyard), the Friends finally acquired the Nobska in 1988 and brought it north. The steamer went first to Fall River, then to Providence, and finally to home waters in New Bedford. At each of these locations, volunteers worked to stave off further deterioration and made small steps toward restoration. In 1995 the boat was towed to the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston harbor where, over more than a decade, a $3 million grant – not nearly enough to do the whole job – and other funds were committed to its dry-docking and restoration. Eventually this long-running grass-roots effort foundered in controversy, apparent fundraising malfeasance by outside groups, and bankruptcy. When the dry dock space occupied by the Nobska was needed for work on other vessels – the USS Constitution, the inarguably invaluable 1797 wooden-hulled frigate, and the USS Cassin Young, a destroyer commissioned on December 31, 1943 – the Nobska had to go. On the last day of May in 2006, a wrecking ball began its attack on the historic steamer, ending the long up-and-down dream of restoring the vessel.

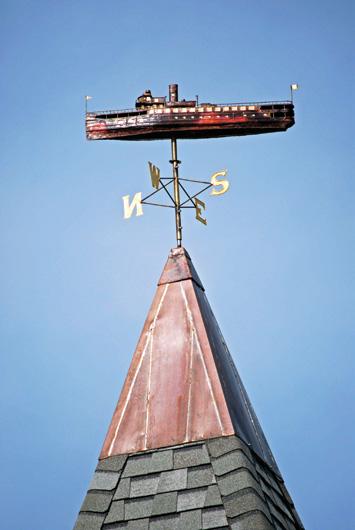

The Steamship Authority didn’t help the Nobska’s cause when in 1995 it refused to license the Vineyard as a port should the vessel be restored. But it has since acknowledged the boat’s place in Island history by installing the Nobska’s whistle (now blown by air, not steam) on the ferry Eagle, its main boat since 1987 on the Hyannis-Nantucket run. Atop the newly rebuilt Steamship Authority terminal in Oak Bluffs, which opened this past May, the cupola overlooking Nantucket Sound is crowned by a weather vane by Island metal sculptor Anthony Holand: a forty-two-inch replica of the Nobska crafted in copper repoussé with gold leaf highlights.

New Bedford, built in 1928

The New Bedford, built at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, served the Islands from 1928 until 1942. Though very much like her two older sisters, this boat had slightly more space on the car deck for automobiles, which caused a reduction in passenger amenities that made this steamer somewhat less revered than her two sisters.

Along with the Naushon of 1929, the New Bedford was requisitioned by the War Shipping Administration and sent to Britain in 1942, where the pair served as hospital ships and troop carriers. Both were part of the Normandy invasion, and eventually both returned to the States, but neither to Vineyard waters. That early Naushon was rebuilt as the excursion boat John A. Meseck for Meseck Steamship Line, running from Manhattan and Jersey City to Playland Park in Rye Beach, New York, and to Bridgeport, Connecticut, eventually ending its career with the Wilson Line. (Laid up in 1961, the former Naushon was scrapped in 1974, at the now-defunct yard in Camden, New Jersey, that had built the Naushon of 1957.)

From 1949 through 1955, the New Bedford ran in summer service from Providence to Newport and Block Island for the Sound Steamship Lines. After a dozen-year lay-up, it went to a noted marine graveyard. On the last day of November 2009, drizzly and dank and dark, I went looking for a boat I’d never seen, this look-alike sister to the lost pair I had known. I traveled to Rossville, Staten Island, on the Arthur Kill, a stretch of water that separates Staten Island from New Jersey. There, among a veritable fleet of derelict vessels at Witte Marine scrap yard, now Donjon Marine (the company that will “recycle” the Islander), I found the New Bedford, sandwiched between a barge and a double-ended ferry. I’d come when the tide was low, and I tramped through marsh grass littered with flotsam and jetsam to the edge of the Arthur Kill’s flats, fresh and strong smelling, a rank yet pleasing aroma that spoke of the water’s edge. Mired in mud, the corpse of the New Bedford was easy to spot. This once elegant steamer – its superstructure and tall stack all red-brown with rust and listing dramatically – was an unmistakable ghost from steamboating’s past.

Nantucket/Naushon, built in 1957

The Nantucket, renamed Naushon in 1974 to clear its original name for a new ferry, was an anachronism from the very first. Delivered by J.J. Mathis Shipbuilding Company of Camden, New Jersey, for Nantucket ferry service in 1957, it was a steamboat well into the age of diesels. Even the Steamship Authority itself had designed and built a diesel vessel, the Islander, seven years earlier. Especially at first, it was not universally loved. Compared to the Martha’s Vineyard, which it replaced, this Nantucket was bulky, a bit ungainly, with a bulging prow and unconventional stern designed to allow run-through loading and unloading of trucks and cars. Unfortunately, the boat’s sheer – the upward sweep of deck, traditionally a mark of maritime elegance – made this unworkable, and the bow sea gate was never used.

This vessel claims the distinction of being the last reciprocating steamboat ever built, though the term “steaming” has survived to describe the progress of diesel-powered vessels such as the Islander. The Nantucket/Naushon was equipped with Skinner Uniflow engines, the most sophisticated of piston- driven steam plants, but its use of steam propulsion made the boat crew-intensive and gluttonous with fuel. However, by the time of its retirement in 1987, the Naushon had become something of a favorite for its spaciousness and the smooth, vibration-free ride typical of steam-powered vessels. The boat offered staterooms, useful especially for the longer Woods Hole–Nantucket journey, that were a link to a bygone era of travel.

After retirement by the Steamship Authority – as the last steam-powered ferry in regular service in North America – the Naushon was acquired by Joseph G. Pallotta Jr. for his Bay State Cruises. He intended to use the boat, probably dieselized, as a floating restaurant and dance hall in Boston harbor, but the Naushon sailed there only once. Pallotta soon recognized the impracticality of his plan, so in March 1989 the boat got a new owner and headed south to Bender Shipbuilding and Repair Company in Mobile, Alabama, for conversion to a floating casino and nightclub. It emerged as the Cotton Club Casino, with a boxy appendage on the top deck and a new, pointed prow reminiscent of the false nose an actor might wear to play Cyrano de Bergerac.

The boat shuttled among casino venues – Lake Ferguson, Louisiana, and Greenville and Lakeshore, Mississippi – finally arriving at its present home in Tunica, Mississippi, far up the Mississippi River at Mhoon Landing, a now-moribund casino site. There it floats in a trench that was dug to bring it away from the Mississippi itself. Sealed off from the channel, which fills only once or twice annually at high water, it still meets the “afloat” requirement for a casino. Some years ago, the water drained out of the boat’s tiny, enclosed world, and it capsized, but it has since been righted. Like the empty casino next to it, the Cotton Club is essentially abandoned, derelict, with no likely future except the scrapper’s torch.

Uncatena, built in 1965

About two years after the Nobska was cut up in 2006, another former Steamship Authority boat went to scrap. This one, the Uncatena, built in 1965 by Blount Marine in Rhode Island, was far less beloved that the elegant Nobska. Its scrapping in 2008 in Florida went essentially unnoticed on the Islands it once served. The Uncatena was sometimes called the “Tin-can-tena,” and I’ve heard that the moniker “Junkatena” was bandied about as well. By the time I met the vessel, it had been “stretched” by the addition of a fifty-two-foot center section.

The Islands were becoming more popular in the 1960s, and the Uncatena had originally been intended as a small, fast, auxiliary ferry to sweep up remnants of traffic that the fleet’s larger boats – the Nobska, Islander, Nantucket – couldn’t handle. It quickly proved too small, which led to its lengthening in 1971 at Bromfield Shipyard in East Boston. Though this extra length added passenger space, stability in rough seas, and crew living quarters, it didn’t do much to improve the boat’s dowdy lines, with the vessel’s windows slightly out of true after reassembly.

The Uncatena ended its Steamship Authority service in 1993. Like many retirees it headed south, to Florida’s east coast, where its new name, Entertainer, reflected its role as a gambling ship for Casino Miami Cruises. “Casino Miami” was bannered across the hull in huge letters, bow and stern were slathered with art invoking the tropics, and the interior bulkheads were adorned with undersea murals. Windows were cut in the car deck walls, as that deck was converted to passenger use, and an upper superstructure was added where originally there had been open deck. Beginning in 1997, the Entertainer began making gambling cruises, but there was too much competition in the Miami area for the boat to be profitable.

Eventually the Uncatena-turned-Entertainer changed coasts, ending up in Tampa. There it was renovated still further, with plans to base it in nearby Tarpon Springs. Then in 2004 along came Hurricane Ivan, which thoroughly disrupted the life of the boat’s Pensacola-based owner, Charles Liberis. By the time he could once again turn his attention to the Entertainer, the Seminole Indians were developing land-based casinos, with which casino boats could not compete, and the vessel was scrapped.

Schamonchi, built in 1978

The Schamonchi, built in Maine, had a decades-long and successful history plying the waters between New Bedford and the Vineyard for a privately owned company. In 2001, the Steamship Authority purchased this bare-bones, passenger-only boat and operated it – at significant losses – through the 2003 summer season. In 2005, after two years in lay-up, it was sold for $105,000 (a fraction of what the Steamship Authority had paid to buy it and docking rights in New Bedford) to Caribbean Shipping and Marine Services of Flushing, New York, and headed for New York harbor. The new owner’s plans were to convert the Schamonchi into a party boat – an all-too-familiar and typically doomed plan but in New York, sans gambling, particularly hopeless. Two years later, it was listed on www.yachtworld.com and sold to a new owner.

I’d nearly forgotten about the Schamonchi until the fall of 2008. While cruising aboard a Circle Line vessel on a charter up Newtown Creek, an estuary of Manhattan’s East River, I saw a boat with familiar lines. Its windows were fogged, and some were boarded over. Tuscan red primer covered swatches of its flank. On the stern, largely obliterated by rust but still legible, was the name “Schamonchi.” On deck, a couple relaxed on a bench and waved to us as we passed. The boat looked a bit like an oversized, under-maintained yacht. Two months later, a feature article in The New York Times explained that five residents, free spirits willing to rough it with no regular plumbing and little heat, now called the boat home. Their 6,000-square-foot floating lodging was properly registered, according to its owner, though iffy as to docking rights. When summer came, he hoped, they might fire up its Cummins diesels and cruise to a less urban setting, someplace like Long Island Sound. Perhaps they did, but when last sighted the boat had been moved to an even more industrial location further up the estuary – English Kills, in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Farewell, my lovelies

Never again will we see the likes of the Nobska, nor her elegant twin sisters, nor even the bulky but historic Naushon, which brought down the curtain on steam ferries. Surely one of these priceless steamboats should still be with us, gliding majestically to the Islands, keeping history alive, but now all that survives are memories. We’ve preserved next to nothing of that era, and those who recognize the value of maritime history from the age of steam are irrevocably poorer. (In contrast, on tiny Switzerland’s lakes, twelve million passengers sail each summer aboard sixteen preserved steamboats, some more than a century old.)

The Steamship Authority still calls itself the Steamship Authority, however, and the current fleet – all of which carry traditional names – will no doubt make its own memories. The newest boat, the Island Home, consciously invokes the Islander with its tapered black hull bands. Some morning in Vineyard Haven harbor, when the fog hangs low, the mists swirl, and the Island Home slides by broadside, you might just think you’ve seen a phantom ship.