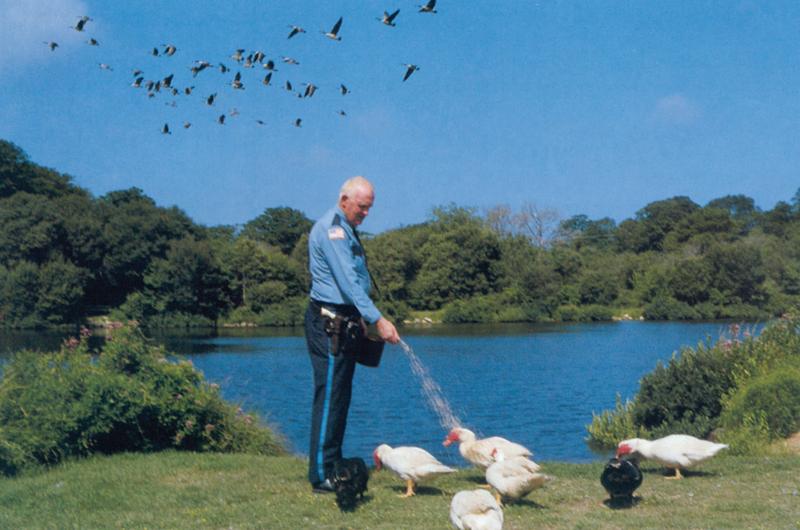

George Manter: Big man, big gun, big heart

From 1988: When he was appointed West Tisbury police chief in 1966, George Manter had three obvious things going for him: a hunter’s acquaintance of firearms, a thorough knowledge of his beat, and, at a strapping six foot four and nearly three hundred pounds, the assurance that he was unlikely to run into anybody bigger. But over the years George has proved he has much more.

“Years ago we used to go what we called ‘hippie hunting.’ Lots of times several young people would gather in the woods and set up camp. Some would have permission, but most didn’t. They would put up tents and build up the area. We had one area up in the Panhandle where the owners didn’t want anybody on their land, even bird-watchers. They called it a refuge. Well, I’d gone up there and found some tent sites, so I advised the campers that they weren’t wanted and to be out of there by the next day.

“I went back and checked in a few days and there were more tents put up. I went back into town and picked up some of the troops, some of the other police officers, and we went back to flush them out of the woods. As we approached the tent sites, one of the campers started to run. I started to chase him through the woods when all of a sudden four or five shots rang out.” George shakes his head. “I was probably as surprised as the other guy. Another officer was only shooting into the air, but still.” George grimaces at the thought of what could have happened.

“To make matters worse, one of the officers got to bragging about ‘hippie hunting’ at the garage the next day and Gerry Kelly of the Grapevine [newspaper] got wind of it, made it public, and we had to have a big meeting with the selectmen. Shortly after that incident, we had another. But nobody ever found out about this one.

“We always have a man on duty in the Agricultural Hall during the Fair, watching exhibits. This one time I had hired a ‘special’ from another town to fill in. He was in plain clothes; I had no idea he was wearing a gun underneath his shirt. I explained to him that sometimes kids get into the cookies or fruits on display, and that they are not to eat them. Most of the cases are locked, but sometimes you can slide your hand in and get a cookie out and it ruins the display. If a kid is caught doing that, he is put off the grounds and can’t come back in till the next day. Then I went home to supper.

“When I came back, an hour or so later, one of my men came up to me at the gate and says, ‘Did you hear that a shot was fired?’ I said no and don’t spread it around. I went into the Ag Hall to investigate and this ‘special’ explained how this kid tried to grab a cookie. He went to grab the kid but couldn’t catch him, and the kid ran out the back door. He chased him across the street and across Up Island Auto’s yard and out back around the Grapevine parking lot. He fired one shot in the air. Just then the kid tripped over a wire and fell down. Of course, he thought he had shot him.” George shakes his head again, rolls his eyes heavenward, and lets out a hearty laugh. “The boy then got up and ran away. This was practically in the Grapevine’s backyard, and it was right after the incident with the hippies....Can you imagine if that had got out then? ‘Officer fires shot at boy stealing cookies!?’ Fortunately, it all turned out well. The boy wasn’t shot and nobody else heard the shot and that was the end of it.”

Update: George Manter retired in 1993 after serving West Tisbury as chief of police for twenty-seven years. He died on November 8, 2003. During his tenure he never carried a loaded gun.

Police chief of West Tisbury for the past sixteen years, Beth Toomey remembers George as a man with extraordinary people skills. “When George was chief, it was before mediation,” she explains. “He had a very Island and old-school way of mediating that was very effective.”

Skipper Manter, the only one of George’s children to work in law enforcement, today serves as a sergeant on the West Tisbury police force and is active in countless community organizations. Looking back, he views his father as a man of great influence. “He touched a lot of lives with his caring, compassionate ways.”

Beth Toomey concurs. “His name comes up every week,” she says. “And his picture still hangs in the police station. People remember George as exactly the kind of chief of police we needed at the time – he had a great presence.”

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Julie Hitchings that ran in Fall 1988. Published with permission of founding publisher, William E. Marks.

Luciana Fuller: A lot more than window cleaning

From 2001: I had people call me back and say the house didn’t look clean because the pillows on the couch weren’t smooth and puffy. And I go back. Because, as I tell them, they’re paying and I want to make them happy.

Once a woman called and said she couldn’t find her wallet. I asked the girls and they hadn’t seen it. And this person got real mad, but then she went out and she found the wallet on the lawn. And she called to apologize.

You can’t get really emotional. I mean, I’m an emotional person and I want people to be happy with the job we do. But I’m learning to deal with that. When you have a business, you have to learn to separate that.

We’ve been in the business about five years. We got big really fast. In the summer we do about fifty houses a week. You see some businesses grow and they forget about doing a good job. They feel they don’t have to keep giving things the same attention. And I don’t want to do that.

We have a house with ten guys in it. We come in two times a week. I mean, it’s unbelievable: clothes everywhere, garbage, lot of bottles of beer, dishes. But personally I like cleaning dirty houses because you can the see the difference. So you feel as if you made something good. Honestly. And I have it on my conscience when we finish to ask, did we do everything?

I came here from Brazil when I was thirteen years old. The type of cleaning we do in Brazil is different because of the way houses are set up to be washed – basically to use a lot of water. I have people who come to work with me who came from Brazil and they just want to use the hose. And you can’t do that. When I train people I show them the way I like to clean my house and I want them to do it the same way.

I have customers I’ve had for years so they really trust me. But I have to trust the girls who do the job. You don’t need to love housecleaning, but attitude is important. And the girls who work for me, I trust them to have good judgment to do the best they can.

We use organic products. We clean the refrigerators, the stove, the Venetians, the floorboards. When people ask, we water the plants. We move the furniture, wash the porch, wash in the drawers, under the sink, take out spider webs.

Summer goes by real fast. It’s hard work. Sometimes we work like ten to twelve hours a day. And then in September it slows down. You’re really busy one week and then the next – oh, my God – it’s over.

Update: When the magazine ran a profile of Luciana in 2001, she was just twenty-two, and she and her husband, Jesse Fuller, had already had their home-and-yard-care business for more than four years. One of the most obvious changes since then is the name of the business – formerly Island House and Yard and now Fullers; Jesse manages Fullers Landscaping and Luciana Fullers Cleaning.

But the most dramatic change in Luciana’s life has been personal: She’s now a mom with a four-year-old daughter, Sofia. Motherhood has had an impact on the business, Luciana says, as she is a mostly work-from-home mom. She still works full-time, but “at this point, I’m more managing,” she says, especially in the off-season.

With the poor economy of the last couple of years, the business has leveled off. But since 2001, she’s had a significant increase in the number of year-round clients, which Luciana prefers because you do develop relationships and it’s a great way to get to know the community.

But when her seasonal clients arrive, there’s a lot less staying at home: “In the summertime, I still do a lot of the cleaning too, especially on the weekends. We have a lot of turnover cleaning then. We do eight houses a day, all in a row. We just keep on moving.”

The edited excerpt above is from an interview by C.K. Wolfson that ran in September–October 2001.

Neil Flynn: The buzz about bees

Farmer at heart, carpenter by trade, Neil Flynn relies on all of his talents for his dual career: commercial beekeeper and general contractor. In 2001, when we caught up with him, he was as busy as, well, a bee. Owner of Katama Apiary with long-time partner Jacquie Balaschak, Neil had started keeping bees in 1994, having discovered that no one else on the Vineyard was producing honey.

A graduate of the Stockbridge School of Agriculture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, he says he always wanted to be a farmer. And by 2001, he had about three million bees in seventy hives across the Island, producing about five thousand pounds of (mostly wildflower) honey each year. He sold the sweet nectar at Cronig’s Market, Morning Glory Farm, through Mulveys Vineyard Dairy, and at the Farmer’s Market, the Artisans Festival, and for a while in a shop he had, called Honey Bunch, in West Tisbury.

Nine years later, Neil’s enthusiastic tone has been slightly tempered by what he characterizes as his worst year in the beekeeping business. A “perfect storm” from Mother Nature – too much rain and destructive new pests including the varroa mite and the South African small-hive beetle – resulted in terrible losses.

“I now have about twenty-five to thirty hives,” he says, the devastation reflected in his voice. He estimates his losses this past year to be 70 to 75 percent. But farmers are a hardy lot and Neil is no exception. “I plan to bring in a large load of new bees from New York to replenish,” he explains. “And we won’t pursue the commercial market this year.”

Instead, he and Jacquie plan to regroup by simply selling Katama Apiary honey directly to consumers at the West Tisbury Farmer’s Market. And, he’s holding out hope that the rule of thumb he’s learned during his sixteen years in the business will hold true: A bad year is almost always followed by a good one. He anticipates a recovery within two years if positive conditions prevail.

“You have to be a real farmer to do this business,” he says. “It’s hot, sweaty, physically challenging, painful work.” In the old days, he explains, bees were of a gentler species. But breeders’ attempts to create more pest-resistant strains has resulted in more aggressive bees. “Getting stung is just part of the deal,” Neil says.

The silver lining? Neil and Jacquie moved from their acre in Katama to a four-and-a-half-acre property in West Tisbury, where they now have enough land to own real farm animals. They recently purchased two miniature (except in cost) Kentshire cows, which are developed for smaller acreage and which they plan to breed.

An article on Neil Flynn by Hollis L. Engley originally ran in Fall–Winter 2001.

John Hughes: The king of crustaceans

“I was doing pretty well at college after I got back [from World War II], but you had to write a paper to graduate. I decided I would write about the Vineyard’s heath hen,” John Hughes says. “I remembered seeing the last one when I was a child and was up at Jimmy Green’s in West Tisbury with my father. We used to go there to get milk and eggs. This bird about the size of a prairie chicken jumped up on a blind. I learned later that the heath hen had become extinct, both because turkeys were introduced and brought blackhead disease with them and because of all the forest fires we had. People would set them in the Depression because you could get money from the state for putting them out. Heath hens seemed, at first glance, interesting enough to write about.

“But after I had turned in my paper, the professor asked me to stay after class. He said the paper wasn’t up to my usual standard. What was the matter? I said I just hadn’t been able to get fired up about the heath hen. The professor came from Michigan. ‘Well, then,’ he said, ‘you come from New England, why don’t you write about lobsters? There’s very little that’s been written about them.

“So that was what I did. I went to the Marine Biological Laboratory library in Woods Hole and got enough information to write my paper. The professor liked it and sent a copy to the director of Marine Fisheries in Boston, who asked me to come to see him, because they were about to start a lobster hatchery on the Vineyard. I ended up designing it and starting it.”

Up until then, lobster hatcheries had been run by college professors on summer holidays, so no year-round study had been made on the lobster, John says. “Because we were there the year around, we were able to watch the whole life cycle.”

At the hatchery, John was able to get a lobster to one pound in twenty months as opposed to the six or seven years required in the wild, largely thanks to the warm water temperature provided and the good food. “This proved that, biologically, lobsters could be raised commercially,” John says.

As for the lobsters raised at the hatchery, once the females had hatched their eggs, they and the fry that had been raised to the bottom-crawling stage in the hatchery were released. “I always wished that we could have released them all in one place. I think we would have learned more if we’d had more all together, but the way the bill that created the hatchery was written, the females had to go back into the same commonwealth waters from which their mothers had been taken.”

As the director, John would painstakingly explain the life and needs of his favorite crustacean. He chuckles about numerous visits from the late master-chef Julia Child, with whom he would discuss the cooking of lobsters.

“She called me once after a visit and wanted to know the most humane way of cooking a lobster,” he recalls. “I told her it was to plunge it headfirst into the boiling water where the brain is, so it would die almost instantly, but I explained that – like a dead eel – it might continue to move for a while.”

John loved his job. “I’d go down to the hatchery every night before I went to bed to see if everything was all right,” he says.

An edited excerpt from an article by Phyllis Méras that ran in August 2007.

Lisa Lane: I lived in a teepee

Our first summer living in the teepee was 1995. We had a year-round rental for one year. Come spring, we needed to move out. Rents were just so expensive – $10,000 a summer. We were trying to save money for land to build a house.

I’d had little experience camping growing up. But I remember that first night thinking, “We can do this because we’ll be living close to the earth.” We were living by the fire at night. You’d wake up in the morning and the rocks in the fire would still be warm and we’d warm our hands. It was simple. Simple, but hard.

I felt like Swiss Family Robinson. You’re out in the woods and you have to make do. It was constant work. Constant housework. The first year, we lived on a dirt floor. After that, we built a plywood platform-floor, which made a tremendous difference.

I’d have friends for a campfire, but I wouldn’t really have them for dinner unless they wanted to cook – you know, bring a dish or stick a corn dog over the fire. We had to keep all our dry food in storage bins to keep the skunks away. We had some come through. I remember my husband one night jumping out of bed naked, fending off skunks with a stick. One year, we lived close to some cows that would come walking through our campsite and leave their presents. The people whose property we were living on built an outdoor shower at their barn, and we’d run down there to shower and bathe.

But it was just so peaceful waking up. We’d brew our coffee in a French press. We did a lot of reading. All we had was candlelight – no electricity.

We moved the teepee at the beginning of the next spring to a property near Peaked Hill, with an amazing ocean view. At that point, I was literally barefoot and pregnant with our second child. We took our showers in Menemsha at the public bathhouse and paid a quarter for seven minutes. Some days I just screamed – cooking the meals, hauling in the water, schlepping to the Laundromat.

It was nice though. We were living so close with nature. The best thing was being close with my family. We were always in one room together, if not outside. It showed me simple living that I don’t think a lot of people know.

An edited excerpt from an article by Lisa Lane that ran in May–June 2003.

Brian and Jennifer Weiland: They found a way to succeed

From 1999: If you fear that Island housing prices are freezing out young people who want to settle here and actively contribute to the community, consider the case of Brian and Jennifer Weiland. It wasn’t easy, but they found a way. After they married, they decided to give the Vineyard their best shot. For Brian, that meant tour buses and nighttime music gigs, while Jennifer worked at the shellfish hatchery when she could and relied on that income-producing staple, waitressing. “We wanted to be here and make it work. A lot of people wanted to help, but there are only so many houses and so many jobs,” Brian says. During their wait for it all to come together, the Weilands saved their bus tour and waitressing dollars, and the day after Brian got his teaching job in music at the Oak Bluffs School, Jennifer was in a real estate office. They now are the proud owners of a home down a dirt lane not far from the school.

Update: When they bought their house, Brian says they were lucky that the home-owner, another teacher, hadn’t allowed a bidding war for her home, as was common then. She knew Brian was a teacher and accepted the offer of asking price. The Weilands have mushroomed to include three children – ages ten, eight, and three. Brian says the first five years with a mortgage were particularly difficult, with trips to the Island Food Pantry in the off-season. Young people he knows now who are in the situation he and Jennifer were in a decade ago are tangled up with affordable housing options. “Without that, I can’t imagine a teacher getting here and being able to make that work.” And whether you own your home or not, the expenses on-Island are high. “It still involves a commitment to living here,” he says. “This is where we want to raise our family.”

The edited excerpt above is from an article that ran in May–June 1999.

Nevin Sayre: Up, up, and away

From 2006: Why is this man smiling? Wearing jeans, sweatshirt, and flip-flops, Nevin Sayre sits sipping a coffee frappe at Linda Jean’s restaurant in Oak Bluffs, gleefully recounting the fall morning he has spent windsurfing in gusts up to forty knots. Such strenuous activity is ill-weaved ambition for most of us, but strictly routine for Nevin, forty-five, the five-time U.S. champion and two-time second-ranked windsurfer in the world.

And yet, his conversation soon turns to another sport, kite boarding. “I got into it because I’d satisfied every goal in windsurfing, and there weren’t many days when I felt challenged,” he says. “You can kite board at eleven to twelve knots, but you need fifteen knots for high-performance windsurfing. That’s actually a big difference on Martha’s Vineyard.” Also known as kite surfing, the sport uses a large, powerful kite to drag a surfboard over water.

“It’s important for people to take lessons first,” Nevin says. “The kite has control over you rather than you over the kite. As is the case with a wild tiger, if you’re safe and give it some love, you’ll have a great time. But if you make a bad mistake, it’ll tear you apart. Kite boarding is a combination of flying the kite, balancing the pull of the kite, and edging the board as if it were a ski. That’s where the finesse comes in. The first skill you learn after going crosswind is to go upwind. You can adapt to riding the waves. It’s like surfing, except with a kite. And there’s jumping. You edge the board up and fly the kite up until it’s at its apex, and you can go twenty-five or thirty feet in the air. You learn to do loops and spins while airborne. It’s impressive, because the wind always blows horizontally. You’re defying gravity.”

Nevin’s life would appear to have defied expectations. The great-grandson of President Woodrow Wilson and the youngest of the four children of Harriet and Reverend Francis B. Sayre Jr., the activist dean at Washington National Cathedral, young Nevin would awaken to find that peace protesters or civil-rights workers had crashed at his house. But an equally strong influence on the Sayre children was their Vineyard Haven summer home and their life on the water.

The professional windsurfing tour proved most profitable for Nevin in 1983, the year he met Swedish champion Stina Hellgren at the world championships in Barbados. Four years later they started traveling together, and they married in 1989. In 1991, Nevin retired from the tour because Stina was pregnant, “and I didn’t want to be an MIA dad,” he says. Nevin and Stina, a fashion designer with her own line of women’s apparel, live in Vineyard Haven with their daughter, Solvig, and son, Rasmus.

Update: Today, though Nevin still admits his passion for kite boarding, he is quick, instead, to point to the athletic feats of his two children. “Solvig, our eighteen-year-old daughter, has Olympic windsurfing aspirations,” he says. “She’s currently top-three ranked in the U.S. among girls and has an outside shot at the 2012 Olympics [in London]. Her real goal, however, is the 2016 Olympics in Brazil.” Rasmus, now twelve, recently won the North American Windsurfing Championship in his age group and, Nevin reports, is equally dedicated to the sport.

Both Solvig and Rasmus are planning summer travel – Solvig to train in Germany with the U.S. Olympic team, and Rasmus to San Francisco for the World Championships. Much of the family’s activities, Nevin says happily, are dictated by his children’s windsurfing pursuits. “Forget about me,” he adds, “they’re the new generation.”

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Jim Kaplan that ran in September–October 2006.

Kelly Peters: We can dance if we want to

From 2002: The kids in Kelly Peters’s break-dance master class trickle into the Vineyard Haven studio in elbow and knee pads, T-shirts that read “South Beach” or “Kelly Peters Dance.” Some in braces, most in ponytails. Their Pumas, red or black, skid and squeak on the shiny new wood floor. “I don’t want to hear any buttons scratching that floor,” Kelly calls out to them.

There are twenty girls and one boy, and Kelly lines them up, and they all start trying to do spins on their backs. Then he gets in front of the class, and someone puts on music, really loud, and Kelly says, “Five, six, seven, eight!” And they all, simultaneously, turn their left shoulders to the wall, stomp forward, and dip their bodies.

In the two years since the thirty-two-year-old St. Louis native arrived on the Island, Kelly Peters has gone from ditching an unsuccessful landscaping job to running occasional hip-hop workshops to having his own new dance space, the Island’s first (and New England’s only) dedicated hip-hop studio. There are a couple of dozen classes, with students ranging from kindergartners to a lot older, and two performing crews who often travel, practice four or five times weekly, and sign contracts wherein they agree to be on time and to be “responsible, humble and positive at all times and not to give their parents any attitude.”

If you mention the name “Kelly” to just about anybody these days, that’s all the explaining you need to do. It’s almost like a religion, with the standard virtues: faith, hope, and love. (And hip hop.) And Kelly Peters is its missionary.

“My mission was about the dance initially. I did not want to be a role model. But right off the bat, one of my students – a tall, awkward kid, very sweet kid – wanted to do break dance....After doing one class, [he] went to one of the teen dances and tried to show his new moves. Some other kids started making fun of him, and completely embarrassed him. I got a call from his mom....I worked on stuff with him, made sure he got extra stuff, quick. And he did. For our first show, at the Pops concert at the high school...he went out there and did his solo, and the crowd went absolutely insane. It changed his entire existence. He had courage and confidence, and he got that from the class, from me.

“My job is to let them know that God has given them a certain contribution, which they have to reach inside and pull out.”

The thought evokes visions of the entire Island learning the language of dance, a generation of kids confident in their own bodies and the way they move through the world. So far, it’s working in this new little studio, one place, on one Island, one ripple in the pond.

Update: The ripples from Kelly Peters’s work with Island kids continue to spread, some well beyond our shores. In 2006, Kelly himself moved back to that bigger pond, New York City, where he is on the faculty of the Broadway Dance Center, and from where he has gained increasingly wider recognition: He has appeared on Fox TV, ESPN, MTV, and other nationally televised networks; released a learn-to-dance hip-hop DVD, Make It Happen; and was the panelist representing choreography for the 2009 Boston Music Conference in September. And he is still working with kids, including some of his Vineyard dancers who are high schoolers here and who tour and perform off-Island; they won the 2009 Clearasil Ultimate Dance Competition held in Times Square last April.

Evan Hall, who is on that team, is a junior at Martha’s Vineyard Charter School and is a Kelly Peters dancer from way back. At sixteen, Evan is already a notable choreographer, having performed his work at the summer Oak Bluffs festival Built on Stilts and Chilmark’s Yard. Evan has taken up his mentor’s torch and is teaching hip hop on-Island, with a range of classes from beginners to advanced at various locations including Camp Jabberwocky and Rise studios, both in Vineyard Haven.

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Jamie Stringfellow that ran in September–October 2002.

Beth Blankenship O’Connor: Ice skater and teacher

From 1992: At age sixteen, Beth Blankenship of Oak Bluffs not only sees her life’s goal, but is already well on her way toward it. In fact she has been since the age of nine. In 1984 Beth began to plan her future life on ice when she saw Paulee Mercier of Edgartown in a skating exhibition at the Martha’s Vineyard Arena. Her plan was to gradually hone her potential to a competitive level. She had the poise, talent, and determination. And she had the vital support that every skater needs, in her dedicated parents, Richard and Nancy Blankenship.

The Blankenships have paid for hundreds of lessons and driven thousands of miles at all hours. And when the Vineyard rink is closed, Beth, who is an honors student, travels to Falmouth and other mainland rinks to practice and to compete Are there Olympic visions? “No,” she says politely. “I want to perform on some level....I am interested in the Ice Capades and Disney on Ice.”

Update: Beth’s dream came true after college when she skated professionally, starting at Busch Gardens in Florida. She later worked for Ice Capades, as well as other promoters staging shows on ice all over North America and the Caribbean, and she still tries to do one week-long show each year. She’s been a penguin and a polar bear; she’s done holiday shows and Broadway on Ice.

After moving back to the Island in 2004, she became a familiar face again at the arena. Now she is a full-time coach for Martha’s Vineyard Figure Skating Club, and she teaches all ages (three to adult) and offers group and private lessons. She’s been on the arena’s board since 2005, and because, she says, “the world of figure skating is always changing,” she continues to attend seminars, conferences, and the like. Beth Blankenship O’Connor (she recently got married) says, “As long as my body holds up and nothing tears or rips or breaks, I’m okay. I’ll keep skating.”

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Jib Ellis that ran in August 1992.

Nancy Slonim Aronie: Teaching from the heart

From 2001: Writing about Nancy Slonim Aronie, founder of the Chilmark Writing Workshops, is like trying to reproduce a Technicolor movie in black and white. Anyone who knows her will empathize. A Vineyarder of more than twenty years, she doesn’t come with fancy packaging, glib clichés, or usually even makeup. Her clothing – artsy, thrift-shop comfortable – graces a lean, athletic body that never seems at rest. Her sun-bleached hair, like the head from which it springs, is witty and has a mind of its own. And anyone could recognize her voice in a crowded airport. Nancy is no shrinking violet.

But, says Arnie Reisman, neighbor, friend, and professional writer, Nancy has two sides: “Jewish nun and a sort of female Lenny Bruce.” The comment alludes to her quick, offbeat humor and a deeply spiritual perspective that frames and supports every aspect of her life.

The writing workshop’s style and format are reflective of Nancy’s strong personal life philosophy: “There is no one who didn’t have trauma. A great way to move forward and cherish it is to write.”

“It’s group therapy; it has nothing to do with writing,” Arnie quips. “But I found it was successful for me because all of a sudden I [felt there was] nothing wrong with me. I’m normal....More importantly, Nancy, always the mother hen, offers an umbrella of safety.” And in that safety, writers, housewives and contractors, teachers and high school students, lawyers, grandmothers, and fishermen learn to trust themselves and each other. In that safety they bring forth the natural writer that already exists.

Nancy estimates that over the years she has taught 5,000 workshop participants. That number is augmented by the course sections she teaches at Harvard as a teaching fellow for the Robert Coles course “The Literature of Social Reflection.” This year Nancy won a Derek Bok Award for Distinction in Teaching, an award voted on by Harvard students. Coles endorsed the award, saying, “She is wonderfully caring, teaches from the heart, and is truly passionate about the redemptive power of the written word.”

“I see what safety does,” Nancy says about her students and why she is so motivated to teach. “I see how their hearts open. I see people fall in love with themselves and their own voices. I see brilliant writing. I see unbelievable results all the time.”

Her life, she says, has required many leaps of faith, always trusting an ever-present and benevolent universe to provide what she needs. She speaks gratefully of the teachers in her life, including the “wintertime Vineyard community.” But first and foremost there is her family. Joel – her husband of thirty-four years, whom she says she “begged to marry her” – she characterizes as “incredibly supportive of every dream I’ve ever had. A perfect partner.” This spring she cheered their son Josh’s efforts to realize his dream of opening a restaurant in Oak Bluffs. For a woman who has made an art of creating safety for others, she has had to confront the painful limits of her own protective power as she and Joel assist their younger son, Dan, who has multiple sclerosis.

She reflects that “[my learning] has taken all these years, with a few naps in between. I call them decade naps....I have learned that when something very difficult happens to you, you have the obligation to feel the struggle and the sorrow of it. But you can also turn it into grace and art. That’s pretty much what I am trying to do with my life and what I am trying to teach in the workshop.”

Update: The past decade has not been a decade nap – far from it. Nancy continues to teach on the Vineyard and at Harvard, and now also at various healing centers across the country, including the Kripalu Center in the Berkshires, Omega Institute in New York, and Esalen Institute in California. Josh has a new restaurant, the Menemsha Café, which he opened in 2008 with his wife, Angela, after moving on from ownership in Park Corner Bistro and Sharky’s Cantina in Oak Bluffs. And Nancy continues to learn, as the most significant change in her and Joel’s life is the death in January of their son Dan.

“I always start the workshops telling people that we’re alchemists; we turn shit into gold. We take the pain of what happened in our lives and we dance it, we sculpt it, we paint it, we write it,” she says.

Nancy is finding that reckoning with Dan’s death is the hardest thing she’s ever done. She continues to look to her family as her teachers. “Joel called Dan a ‘Perspective Guru,’ but Joel really was the Zen Master; he never judged [Dan’s illness] as good or bad, he just stayed totally open....He was my guru for that one.”

Nancy cancelled a series of spring workshops – something she’d never done before – to give herself time to grieve and let go. She says, “Dan was a brilliant example of letting go of needs. His needs came down to bare-bone essence. As he got distilled, he became more refined. [Our friend] Gerry called him a raisin: that the sicker he got, the sweeter he got; that the smaller his body got, the bigger his spirit became.”

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Kay Goldstein that ran in September–October 2001.

James Taylor and Carly Simon: Livestock ’95

From 1995: It was, in a word, magic. What began as a simple, benevolent gesture by two Island music legends became the largest one-night extravaganza in the history of Martha’s Vineyard: Livestock ’95, the dazzling James Taylor–Carly Simon concert held August 30 at the new Agricultural Hall fairgrounds in West Tisbury. Billed as “a private party for 10,000 people,” the concert attracted fans from across the Island and the mainland for an exhilarating two-and-a-half-hour show.

The concert marked the first performance in sixteen years for the former husband and wife singer-songwriters, and the evening lived up to its pre-show hype with many emotional, nostalgic moments. At the end of the first set, Carly joined James for his song “Shower the People,” and later, the pair hooked up for a sassy rendition of “Mockingbird,” their classic duet from the 1970s. Other pairings followed, and in addition to the duets, both James and Carly delivered knockout solo performances. Carly dedicated “Nobody Does It Better” to James, and was later joined by Aerosmith lead singer Steven

Tyler for a sexy, rollicking rendition of “You’re So Vain.”

The multiple standing ovations from the audience confirmed the enduring appeal of both James and Carly on the Island; both stars maintain homes on the Vineyard and have lent their names to a variety of Island charities. On the Vineyard, James and Carly are considered family, and Livestock ’95 took on the flavor of a long-overdue and joyous reunion.

The concert sold out its 10,000 tickets in a stunning four hours, causing hundreds of people to sign up for volunteer tasks such as parking cars or ripping tickets just to get a place inside. Organizers held firm to the promise of keeping the concert a local event; national media outlets were blacked out and the standard trail of VIP ticket holders had to wait in line like everybody else. There will be no compact disc, pay television show, home video, or movie of the event. We are left with only memories of Carly and James dancing across the stage together in song, but they are vivid memories, ones that will be impossible to forget.

Update: Carly and James have not performed together since Livestock ’95. James frequents Martha’s Vineyard less often these days, as his home base is

now in Western Massachusetts. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000, and though it doesn’t include a Vineyard stop, his 2010 Troubadour Reunion tour with Carole King has multiple performances on the East Coast, including in Boston in June and Lenox in July.

Carly still maintains her home here, as well as a visible presence in the community. Over the past fifteen years she has released more than a dozen albums, including her March 2010 release, Never Been Gone. It’s still officially a mystery as to which man in her life inspired “You’re So Vain,” but recently Carly’s 1973 hit has been the subject for more than discussion, with a “You’re So Vain” video contest for New York’s Tribeca Film Festival in April.

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Jason Gay that ran in Fall–Holiday 1995.