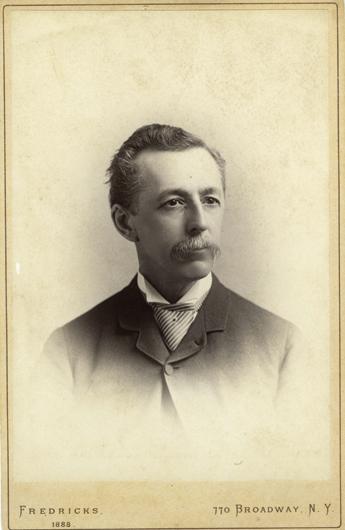

Let’s imagine W.R.G. Mellen walking (or riding horseback) to his first day of work in the middle of June 1863. If he were anything like a government employee today, he’d have hoped for a quiet morning and afternoon of reviewing correspondence, thumbing through the files, and sizing up his new employees. But given the fact that he was taking up the post of American consul on the tiny island of Mauritius, which lies five hundred miles east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean – and given the fact that on the other side of the world the United States was fighting a savage rebellion that required enlisting every man who turned up at the recruiting office – chances are pretty good that there were no employees in his new office to size up. So it’s fair to conclude from the given circumstances – together with the number of times he used the first person singular when writing later about what had happened – that what W.R.G. Mellen was about to face that first morning in Mauritius, he probably faced entirely alone.

After it was over, it took him a few days to collect his thoughts. But then, on June 29, 1863, he sat down and tried to make sense of it all in a written report to Frederick Seward, the assistant secretary of state – whom Mellen might have imagined was sitting pretty back home in Washington, dealing with matters that, even in a time of civil war, were far less delicate, complicated, and astounding than this one:

I beg leaveto call the attention of the Department to a very singular case, which was brought to my notice on the very first day of my official career. It is that of a young American woman, who, as she says, after having served some months in our volunteer army in man’s attire, had shipped, in the same disguise [aboard] an American whaler, where she did a seaman’s duty for several months without exciting suspicion, but whose sex was at length discovered, and of whose presence, the Master on arriving at this port, demanded to be delivered.She was at once removed from the vessel, and her immediate wants provided for. As she had practiced so great a fraud upon the master, had done no service for five months, had caused so much annoyance by her presence after the discovery of her sex, and was largely indebted to the Bark [the whaling vessel].I exacted no “extra wages” of the master. From all I could learn, the conduct of the master, Capt. John A. Luce of Tisbury, in the delicate predicament in which he found himself was in the highest degree honorable to him as a man and a gentleman.I succeeded in shipping the young woman in her own proper attire, and under her own name as steward of the American ship “Renown,” Capt. Bangs, who, from the promptings of a large, generous, Christian heart consented to give her a trial. The [Renown] is still in port, and I am happy to say that the young woman is acquitting herself to the satisfaction of all concerned. Several Americans here have kindly contributed to her wants; and the Consulate has disbursed for her twenty dollars and twenty cents ($20.20) as will appear by vouchers forwarded to the 5th Auditor, and which I do not doubt will be refunded by the Gov’t.

Still rattled by how much the business had strayed from any directions he could find in his consular manual, Mellen added a faint plea for further guidance, should anything so downright weird ever happen at his outpost again:

If my conduct in this case meets approval, I shall be happy to know it; and I shall be glad to receive instructions as to how far I shall go in relieving any of my destitute countrymen

And here Mellen could not help but hammer home the disorienting irony in the whole business to his boss:

or countrywomen, other than seamen that may be thrown helpless and destitute within my consular district.

It’s a challenge, 145 years later, to pull threads of truth from the shroud of legends that cloaks the story of George Weldon, the woman who shipped as a whaleman aboard the bark America, the last whaling vessel ever to sail from the harbor now known as Vineyard Haven. The record is embroidered with speculation, fantasy, and florid prose, and it takes close reading to determine – just for instance – that both George Weldon and Captain Luce probably each lied at least once in their sworn statements to the rookie consul, for reasons we’ll investigate in a moment.

The real problem in assembling an accurate history of George Weldon (or as some accounts spell it, Welden) is that apart from a single, cryptic entry in Captain Luce’s log on the day of Weldon’s discovery, and Consul Mellen’s report to Seward nearly six months later, there appears to be no detailed, firsthand account of what actually happened aboard the America between her departure from the Island port then known as Holmes Hole on September 10, 1862; the discovery of Weldon’s true sex not far from the Falkland Islands on the afternoon of January 9, 1863; and Weldon’s delivery to the consul’s office at Port Louis, the capital of Mauritius, sometime between June 13 and 18 of that year.

What primary sources we do have come from the tales of two veteran Vineyard whaling men, who began to tell their stories to New Bedford and Island journalists not less than forty years later. In those days, reporters didn’t quote sources as specifically as they do now, and you need to look for overlapping recollections to cut through embellishments such as this, from a 1903 New Bedford newspaper story about the affair:

Like a tiger [Weldon] flew at the mate, springing completely over the after thwart. In a twinkling he whipped a sheath knife from the belt of the sailor sitting in front of him and raised it for a plunge into the offending mate’s vitals. His eyes gleamed like those of an infuriated beast.

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

Comparing histories and carving away potboiler prose is the only way to guess what the witnesses themselves actually saw and personally remembered. But 145 summers have passed since the world began to learn from a consul’s report of this remarkable woman who shipped out on a Vineyard whaling vessel as a man – time and reason enough to give the truth another try.

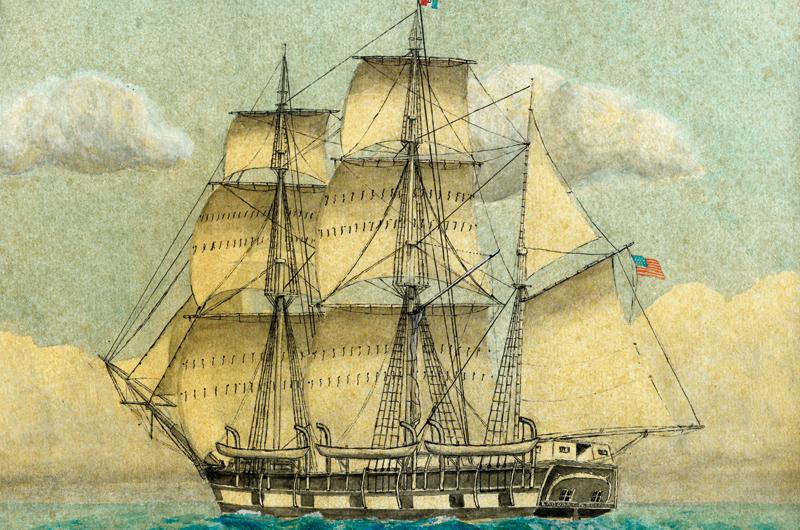

The America was an old ship, and the last of a small fleet of whalers to call Holmes Hole her home port, when she sailed from the Island for the last time in the late summer of 1862. Built in Duxbury in 1818, she measured 258 tons and was 95 feet long (just 13 feet less than the topsail schooner Shenandoah, moored in Vineyard Haven today). In these final years the America sailed as a bark, her first two masts rigged with square sails and her third with a gaff-rigged mizzen sail. We know that three Holmes Hole men were serving as her principal owners as early as 1855 – the most famous among them Thomas Bradley, a former whaling captain who was then a leading entrepreneur and office holder in the town of Tisbury, of which Holmes Hole was a part. Her master for the third consecutive time would be Captain John A. Luce of Lambert’s Cove.

Though prices for whalebone for corsets and parasols remained high – as did spermaceti for candles and oil for lubricants and lanterns – whaling was an industry in eclipse in 1862 when Bradley and his fellow investors were readying the America for a voyage to the hunting grounds of the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean. Oil had been discovered in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. Whales were increasingly hard to find. And with the Civil War grinding along, so were the men needed to sail a whaling ship and hunt her prey, according to a New Bedford story about the Weldon drama:

Those were the days when men were becoming scarce, especially sailor men, for Uncle Sam was offering experienced mariners far more than the average whaleship owner could.In desperation Mr. Bradley resorted to advertising and took gladly whatever came along. He even went to New York and Boston to coax men, and from one of these two ports – no one knows exactly which – “George Welden” was [signed on].

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

Desperate for a crew though he may have been, Bradley would have asked Weldon for his story before hiring him on the mainland, and the tale Weldon told – cryptically at first – was remarkable, even in a time of rebellion. What we know of it comes from Jethro C. Cottle of Edgartown, who served as third mate on the voyage. Cottle, who would retire as a whaling master in his own right and become an Edgartown real estate agent in his old age, described Weldon and recalled the recruit’s story, with the help of a reporter, this way:

“George” came aboard the America at Vineyard Haven. He was a rugged, healthy ruddy cheeked fellow, rough in exterior perhaps, but apparently by effort and artifice rather than by breeding. He stood perhaps five feet nine inches in height, was possibly 22 or 23 years of age, had a frank, open countenance crowned by thick curly hair. He weighed not 165 pounds. Something about him suggested that he was well bred but had, by contact with army life and prison association, acquired a coarseness which ill fitted him.

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

“Army life and prison association”: Here’s how Cottle remembered Weldon’s first days aboard ship:

The new sailor admitted that he was a paroled rebel prisoner, just discharged from a Union prison after taking the required oath of allegiance to the old stars and stripes. Cast adrift penniless in a strange city, he sought almost any chance to get away from an unsympathetic community; it mattered little where he went, so long as he got away from the despised Unionists and from certain other memories which made life amid almost any society hateful. And so it happened that the chance to ship [on a whaling vessel] was a literal Godsend to the ex-Confederate soldier.

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

But Weldon could not have signed on to a Yankee whaler at a more awkward moment for a veteran of the rebel army. As the bark weighed anchor in Holmes Hole harbor on September 10, 1862, details were arriving about the rout of Federal forces at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the last days of August – and of the rising panic in Washington as General Lee’s subsequent advance threatened the capital. The first stop for the America, after a sail of just a few hours, was New Bedford, where she was to spend the next two months provisioning and fitting out. Not long after her arrival there, her crew would have learned additional news that, as seafarers, would have affrighted them deeply: On September 5, the newly commissioned Confederate raider Alabama had captured and burned her first Union ship of commerce, the whaler Ocmulgee, which had been busy cutting into a whale off the coast of the Azores. The Ocmulgee, as every man aboard the America knew, or would immediately learn, was an Edgartown ship, and her captain was Abraham Osborn, descended from the most prominent and wealthy family of that town.

Hunting whales, never a safe or easy way to make a living, must have suddenly felt particularly perilous to the crew of a Vineyard whaling vessel heading out to sea. George Weldon, who had so recently fought for a rebellion that was then riding high, knew right away that he needed to show a tough and memorable side to his New England shipmates as the America set sail for the South Atlantic on November 15, 1862:

No one could spin a tougher yarn, dance a cleverer jig or do a more daring stunt [recalled Jethro Cottle].That he was clever with his fists was clearly proven one day, when in a little misunderstanding with a Negro cook he wiped the floor with his antagonist in such approved fashion that no further disposition was manifestedto brew any trouble with him. A good fellow when calm, he was rated a bad man when aroused. When he explained the ugly red scar on his head by narrating a wild cavalry charge in one of the early battles of the war, and telling how his horse had thrown and trampled on him in the clash of the contending lines there was no disposition to doubt his word. He looked all he said despite his fair face.

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

But Cottle thought there was something odd about the Southerner, and “a couple of weeks out,” he mused to his fellow officers that if “George Weldon wasn’t such a tough cuss,” Cottle should think he was a woman. The officers laughed. Cottle let it go.

Among other virtues, Weldon was also a quick study. When the first whale was sighted, Cottle asked for volunteers among the green hands to man his boat. A New Bedford journalist wrote:

First among those who came forward at the call was George Welden. Jethro Cottle steered the boat and George Welden pulled an oar. They went after the whale and they got him. Nobody took to the business more than Welden and nobody put more beef into it. So says Jethro Cottle and he should know.

– The New Bedford Sunday Standard, April 1, 1917

The America eluded Confederate pirates, slipped below the equator, and in early January 1863 found herself cruising about four hundred miles north-northeast of the Falklands. The hunt had been unusually good in this part of the South Atlantic. During the midday meal on Friday, January 9, whales were sighted and the boats quickly lowered. Weldon was assigned to the boat commanded by second mate Robert G. Smith of New Bedford. Weldon sat nearly amidships, pulling the tub oar, among the longest and most challenging in the boat.

All the histories agree that at some point during the chase, Weldon flagged at his oar, and Smith accused him of shirking. Weldon denied it. Smith picked up a paddle and swung at Weldon, striking him either on the shoulder or head. What happened next varies profoundly with every telling, one declaring that Weldon sprang at Smith with a knife grabbed from a neighboring crewman and that Smith leaped overboard to escape Weldon’s stab “by a fraction of an inch,” another saying that “only an oar kept them apart.” Excise the most melodramatic interpolations, and you’re left with the report of Barkley Renear, an Islander who ultimately gave the most sober account of the whole saga, including important details that research many years later would verify. After Weldon was struck by the paddle, Renear said that:

George turned and took a knife from the pocket of a Portugues [sic] sailor next to him and made as if to stab Smith, but they grabbed George and took away the knife and threw it overboard. The crew then pulled for the ship and came aboard. When they did so, Captain Luce asked, “What’s the matter now?” Smith said: “I’ve got a man that drew a knife on me.” Captain: “Let him come aboard and I’ll show him how to draw a knife on one of my officers.”

– The Vineyard News, date unknown, 1919

The three oldest newspaper stories again differ sharply on what happened after Weldon was bound to the mast for a flogging. In the 1917 account, Weldon “seemed to crumple up” and “called the captain over and said something” before the first blow was struck. Barkley Renear in 1919 recalled Weldon receiving one or two lashes before defiantly asking Luce: “Captain, do you know whom you are striking?” The 1903 recollection by Cottle hurtles into the realm of The Perils of Pauline:

Yer will mutiny, will yer?” shouted the captain, plying the lash again. “Just peel his back, boys, and let’s see how this cat feels on his cussed hide.” The prisoner at bay gave one fearful yell. “Stand back, you cowards,” he hissed. “Don’t disgrace your manhood by striking me. You don’t know what you’re doing. Call me vile names if you will, but I’ll kill the first man who tries to touch me. I am no man. I’m a woman.”

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

Cottle, with the assistance of his interviewer, whose language now veered feverishly into erotic metaphor, described the shock on the main deck of the America:

The captain’s arm dropped limp by his side and the “cat” fell harmless to the deck. Welden, bound fast to the mast, glared like a veritable tigress at bay. Men who had faced death in the chase of a whale or had laid aloft in the teeth of a howling typhoon, drew back, completely cowed by the terrible ferocity of those blazing eyes. Not a word was uttered, but somehow not a man had the mind to doubt a syllable of the dramatic disclosure. The silence was painful, but not for an instant did the captain’s eye leave those of that commanding figure standing erect before him.The heaving breast, the fierce look of defiance, the tense form, as straight as an arrow and drawing to its fullest stature, all breathed pent up in indignation. It was the living idealization of “Womanhood Aroused.”

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

Weldon was led below decks, where a quick inspection determined that she was telling the truth. That night, on page 28 of his logbook, Captain Luce put the day in context as only a veteran whaling master, who until that afternoon thought he had seen it all, could:

Bark America in the South Friday January 9th 1863. Coms with light breeze from W[,] the Boats in chase of Whales at 3 PM the Boats come onboard[.] this day found out George Weldon to be a Woman the first I ever suspected of such a thing[.] at sunset took in Sail[.] Latter part fine breezes from S by W[,] steering by to E.S.E[,] three sails in sight. Latt 46.00 Long 56.20.

– Captain Luce’s log, 1863

For the next five months, the bark hunted in the South Atlantic, laying over briefly at St. Helena, and then rounding the southern tip of Africa. One report said that Weldon – of necessity still dressed as a man since there were no women’s clothes aboard – had traded places with the cabin boy and was serving as a steward to the officers. Weldon now told her bedazzled shipmates a fuller version of her life story. She was, she said:

Well bred and proud of her lineage. Her father was an ardent Confederate, and at the outbreak of the war had left his Maryland home and enlisted as a cavalry colonel. The girl was about to become the wife of a young fellow in Baltimore, but he too caught the war fever and enlisted. “George” never knew quite what regiment he was in, but she was determined to follow him, even to the grave. Accordingly, she disguised herself in men’s attire, applied to the recruiting sergeant and was assigned to the regiment of her own father as a cavalryman. Being an admirable horsewoman she managed to live the part very well and become a good soldier. Her disguise was so complete that though she was often near her father, even he failed to discover her identity. Her cleverness in disguising her sex and the fact that medical inspection of recruits was less strict than now accounted for the success of her masquerade.

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

According to the log, the America dropped anchor off “the bel boy” at Port Louis and lay there between June 13 and 18, 1863. Captain Luce and George Weldon rowed ashore and arrived at the consul’s office on his first day in charge. Luce and Weldon seem to have worked out a deal before swearing to personal affidavits now missing from Mellen’s report at the National Archives: The captain would not reveal that Weldon had in fact fought for the rebels (and not, as Mellen wrote, “our volunteer army”), and Weldon would let Luce say that she had done no further work after her discovery and was therefore owed no “extra wages.” Weldon was put aboard the clipper ship Renown as a stewardess, and what happened to her after that is – as are so many other things Weldon – a matter of conjecture.

What we do know is that at Mauritius – if not before – George Weldon gave her real name as Georgiana Leonard (spelled various ways in various accounts); on this point Barkley Renear and a brief reply from Frederick Seward to W.R.G. Mellen in August 1863 agree. We also know that during that voyage the America returned to Mauritius exactly one year later, on June 14, 1864, and Cottle recalled that by chance the Renown was again in port, with Weldon still serving as a stewardess:

She came on board the America and visited her old shipmates, who found her a neat, prosperous looking woman, without the least suggestion of her former career. She confided to Captain Luce that she had fallen in love with the second mate of the ship and was soon to marry him and settle down ashore.

– The Evening Standard, May 9, 1903

The America returned to New Bedford after a successful trip and was dismantled in 1865. Legend had Weldon also returning to the city and affiliating herself with a small bar on the waterfront called The Sailorboy. One story declared that “she was the principal attractionalthough her drawing power very likely declined in later years.” Another legend averred that Weldon herself was for many years the owner and “always served as her own bouncer.”

The most satisfying conclusion to the story comes from Orin L. Romigh, the great-grandson of Captain Luce, who inherited the logbook of the fateful voyage. To reporter Suzanne Stark, who wrote about Weldon in the magazine The American Neptune, Romigh wrote that his late mother, Viola Luce Romigh, knew firsthand how the Weldon business had played out:

[My mother] spent a lot of time with her grandparents at their home on their farm in Lambert’s Cove. After I told her of reading about George Weldon in the log she told me that it was a well known story among the family.After George returned to the States, she married and during her married life she and her husband visited my great-grandparents home a number of times and...the two families were very friendly.

– The American Neptune, winter 1984

But Captain Luce died in January 1902, and the newspapermen who began to record the story more than a year later knew of no such meetings between the two couples. They were thus left with nothing but speculation and sentiment, at which they all excelled. An undated clipping from an unknown paper gives this summary, at once romantic and cogent:

Somewhere in the world there may be a gray-haired old lady, somewhat bent and somewhat wrinkled. As she sits and sews and the shadows lengthen she may be thinking of the Bark America on the South [Atlantic] in January 1863.She must have been an individual out of the ordinary run, but her motives and her secret self can never be known. If it had not been for the second mate’s [paddle] she might have finished the voyage, and the world might never have known of the strange case of George Welden who tried to kill the second mate and turned out to be a woman.

– Files of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, Edgartown

Assistance with research for this story came from the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Edgartown (curator Dana Costanza Street and assistant librarian Linda Wilson); the New Bedford Whaling Museum (Stuart M. Frank, senior curator; Michael P. Dyer, librarian and maritime historian; and Laura Pereira, assistant librarian); and the archives of the Vineyard Gazette (librarian and director of research for the magazine, Cynthia Meisner).