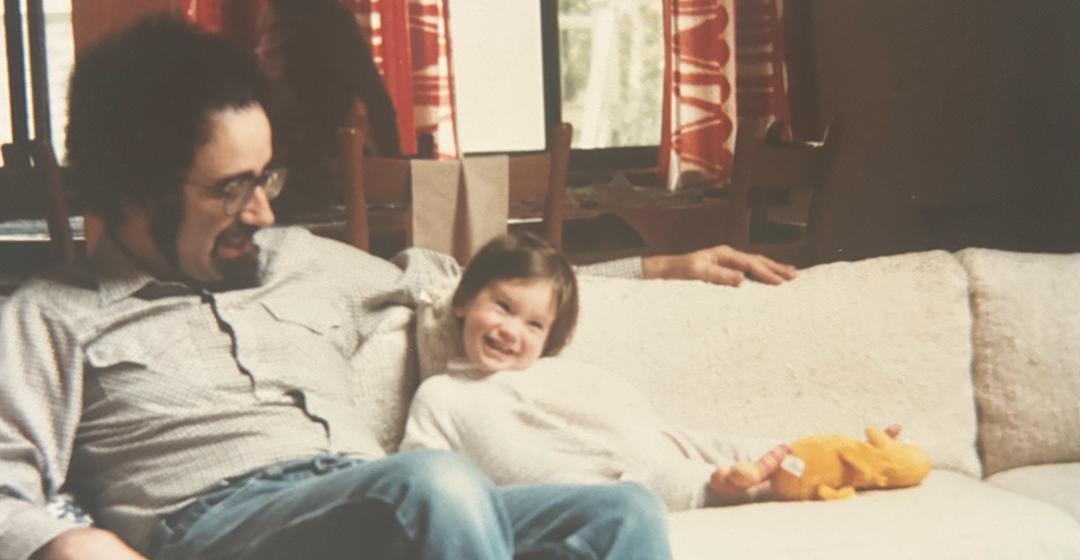

I was sprawled out on the couch under a blanket, home sick with a stomach flu over a high school winter break. My dad, Ron Rappaport, had left work early, trading his suit and tie for jeans and a flannel, and had nestled into the tiny sliver of cushion I wasn’t occupying. We were midway through the 1998 Adam Sandler–Drew Barrymore rom-com The Wedding Singer. As Barrymore’s character, preparing to get married, exclaimed with a grim realization, “My name is going to be Julia Gulia?” I looked over to see tears streaming down Dad’s face.

“What?” he asked with a sniffle. “It’s a very touching movie.”

I nodded, but didn’t say anything. It is a sweet movie, though not necessarily a tear-jerker.

Still, it wasn’t a surprise to see Dad crying. I had seen him cry many times before. The surprise was what he was crying about – a rom-com – because up until that afternoon, I had only ever seen him cry when he was telling stories about his own dad, who had died suddenly and unexpectedly two years before I was born.

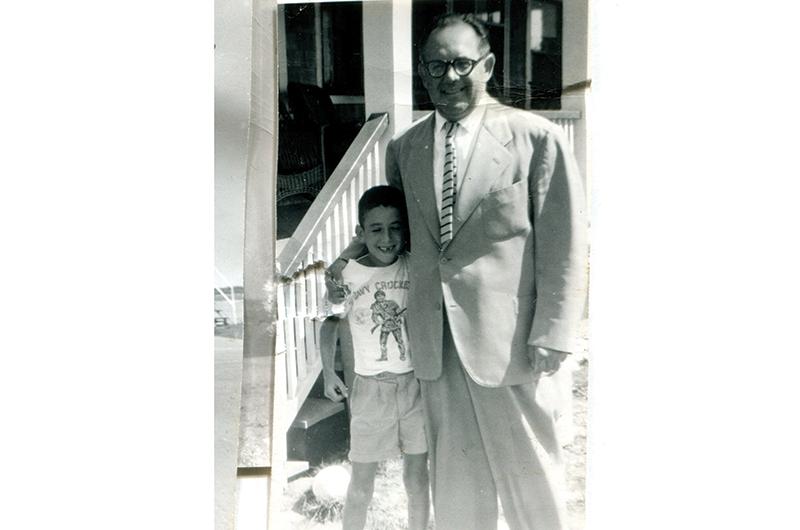

Dad’s dad, David Rappaport, or “Papa D” as my oldest cousin dubbed him as a toddler, was a well-known and beloved Island physician when he died in 1982 at the age of sixty-seven, just as he was getting ready to retire from his medical practice. My dad was thirty-two when it happened. Nearly two years to the day later, during a March snowstorm, he would become a dad himself – something his own father would never know him as. And yet, over the course of my lifetime, Dad did something amazing with his grief: He built a picture of a loving, smart, fun grandfather for me, one that I feel as though I know just as much about as the three grandparents that were alive during my lifetime. He also modeled for me a beautiful portrait of how to grieve, how to love someone continually though they are gone, how to exist in pain, and how to build a successful, fulfilling life while you are alive without them. I came to understand this only after my own dad died suddenly, unexpectedly, in June 2024, just as he was getting ready to retire.

Dad loved to tell stories about Papa D. Often the tales emerged on the weekend outings he and I would take – Dad spelling my mom after she had done more of the parenting during the workweek. (A lawyer, he was council to five of the six Island towns as well as the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission, so there were always long hours and evening commitments.) We’d usually start with a visit to the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Cemetery in Vineyard Haven where Papa D is buried. We’d meander slowly, hunting for white rocks, which Jews place on the headstones of their loved ones to keep their memories alive. As we collected our stones, Dad would tell his stories and, often, he’d cry.

One time, Papa D used an old-fashioned bicycle horn to save a baby born with lungs that didn’t kick-start correctly. He ran out of the delivery room, found the horn on a bike, and took turns with the baby’s father squeezing its bulb until the baby could breathe on its own. The baby survived.

And: Papa D was a Jew in Oak Bluffs at a time when the deed for the East Chop property he and my grandmother built their house on unconstitutionally barred ownership by Blacks and Jews. When he joined the nearby East Chop Beach Club, he subsequently became the first Jewish member. At the time, Dad asked why he would want to belong to a club that historically had no Jews. Papa D responded: “I work hard all day. At the end of the day, I want to walk down to the beach and go for a swim. You don’t have to go.” (Always a beach lover, Dad in fact often did go on to join him.)

And: He always picked people up from the ferry. He didn’t believe in letting them walk or take a taxi. He’d show up in his car, nicknamed Belly Acres, to welcome them to his Island home.

Eventually, the stories would run their course, Dad would dab at his eyes under his glasses, and we’d place our rocks on Papa D’s headstone. From there we’d drive over to see friends of my grandparents – stopping in Vineyard Haven to catch up with Dr. Bernie Issokson, who at one time had shared an office on Circuit Avenue with Papa D, and his wife, Helen; or heading to Dad’s hometown of Oak Bluffs to visit with Pat (who was Dad’s sixth grade teacher) and Kerry Alley. Dad was checking in with his dad’s friends and, in that way, keeping those relationships and that connection to his father alive for me.

I don’t know the sound of Papa D’s voice, or the way in which he moved through a room, but I’ve seen the photos of his infectious smile – the same smile Dad inherited, the one I’m told that I have and have passed on to my oldest. I’ve met Papa D’s friends. I’ve heard the words used to describe him: warm, fun, smart, kind, generous. And I’ve heard the stories about him, often delivered by Dad, but just as frequently told to me by other Islanders as I was growing up year-round on Martha’s Vineyard.

We had a charge account at down-Island Cronig’s when I was younger. When there without my parents, I’d give my last name at the register to charge it to the account and the cashier would ask, “Are you Dr. Rappaport’s granddaughter?” Upon hearing yes, they’d launch into a story (“He delivered me,” “He delivered my daughter,” “This one time he…”) or simply say, “Oh, he was the nicest man.” In those days the question was never “Are you Ron Rappaport’s daughter?” though, of course, as my own dad became more established, more ingrained in the community, that became the dominant question. Even now, at age forty-one, I am still asked if Dr. Rappaport, a man I never met, was my grandfather. Just this fall, while wearing a Bad Martha sweatshirt and picking up a prescription in Newton, Massachusetts, the woman behind me asked if I was from Martha’s Vineyard. We chatted for a moment and when I told her my name her hand flew to her heart: “Your grandfather delivered me.” Those stories carried on Papa D’s legacy for me. And they did something more. They said, “He was a part of us, he was a part of Martha’s Vineyard, and you are too.”

Papa D’s legacy was also carried on in the way Dad conducted his life. In the months following Dad’s death, I’ve often wondered, would he have moved back to the Island to start his own law firm if Papa D hadn’t died when he did? I was just months old when my parents started commuting from Boston to the Island for the work Dad was picking up here, work he started doing because he was spending more time on the Vineyard to get Papa D’s papers in order after his death.

Regardless of what prompted the move, in 1986 my parents opened Reynolds, Rappaport & Kaplan LLC in Edgartown with partner Jim Reynolds. For Dad, the firm quickly became more than a nine-to-five law practice. He devoted his life to caring for this Island community, nurturing its young people, and protecting the unique and intrinsic way of life we have here. Whether it was on town meeting floor as town council; as the Vineyard governor for the Steamship Authority, a position he held from 1993 to 2000; as part of one of the numerous community boards he sat on; or by acting quietly behind the scenes to champion great endeavors, such as the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, Family Youth Tennis (now Vineyard Family Tennis), or TestMV (the free, rapid testing service that served the Island community, insured or not, during the Covid-19 pandemic). Dad was a man of the people. If, of course, the people happened to be Martha’s Vineyard people – and best wishes to you if you were an outside force trying to jeopardize his Island home. This, of course, was the way he had seen his own dad live.

Grief, Dad taught me through all this, needn’t always be bad or scary. It can be beautiful, subtle, inspiring, comforting too. It can change and drive career paths. It can build legacy through actions – from participating in community, to picking up friends at the ferry, to sharing stories so that others, familiar and strangers, may know and remember the one you’ve lost. It can seem like even though they are gone, they are still close by. In my case, I grew up feeling like I knew this grandfather that I never met, something I hope I can recreate for my own two sons, who were just three and thirteen months respectively, when Dad died and will likely not remember him.

By watching Dad’s grief over the course of my lifetime, I know now, after his death, how remarkable it was that he cried that evening watching The Wedding Singer with me. Yes, it was remarkable because that movie is so hokey. But, I see now, it was also remarkable that, after about eighteen years, Dad had finally found something to cry about besides the loss of his dad. To me, now fresh in my grief, I have trouble wrapping my head around the fact that he was ever able to cry about anything else.

In the years that followed I saw him cry much more frequently: at weddings, when friends of his died, during movies other than The Wedding Singer. And I saw him laugh. I saw him travel. I saw his professional success skyrocket. I saw him become a great, empathetic, supportive dad and a loving, soft, up-for-anything grandfather. I watched him be with his grief, and, also, sometimes without it. Most of all, I saw him keep on living. In these days when my own grief is still so new, it’s a comfort to remember that there were the days in which he only cried about his dad, and then there were all the days after. That it’s okay to cry for eighteen years, or more, if I need to. That even though my sons may not remember him, they may feel, too, like they know him – really know him. That through these ruins, something beautiful can also exist, and he will be a part of it, even if he is not by my side in this world any longer.

As part of grieving Ron Rappaport and continuing his legacy, the family has set up a scholarship to honor the work he did on the Island. Learn more and donate at mvbank.com/honoring_ron_rappaport.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)