My most vivid experience with bluefish lasted only a few seconds, although it seemed to play out in slow motion. I rowed out to some feeding blues and was standing in preparation to cast when movement, only a few feet away, caught my eye. It was a small menhaden – a “peanut bunker” – with its tail bitten off by a blue. Bleeding, the peanut circled on the surface, frantically struggling to survive. I leaned over the gunwale to get a closer look when a blue ascended vertically into view directly below me. With its face only inches under the water, it stopped, undoubtedly surprised to see me staring right back at it. We froze, hunter to hunter, eyeball to eyeball. The blue then rose and swallowed its prey, descending silently out of sight. An unforgettable moment in an eat-or-be-eaten world.

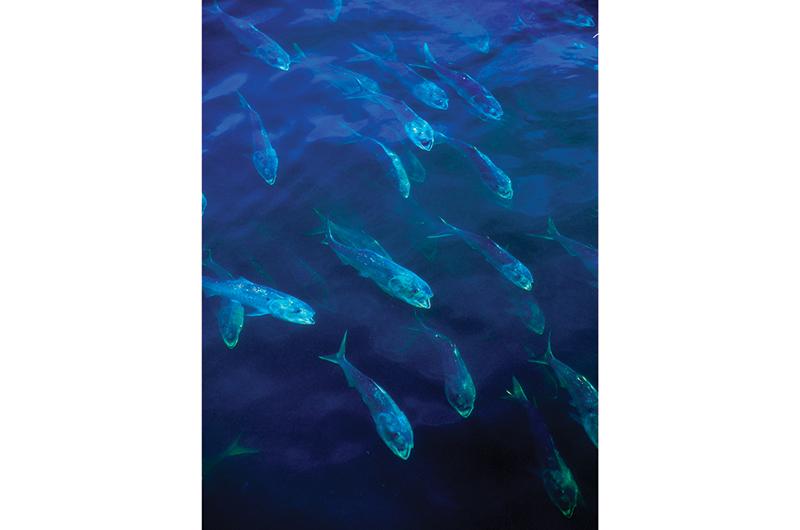

Ferocious by nature, bluefish roam the seas armed with razor-sharp teeth and an insatiable appetite, ripping and tearing apart prey under a cloud of screeching gulls. Blues live about thirteen years and can grow to nearly thirty pounds. Their raucous, wild behavior has earned them many monikers. Big blues, those over ten pounds, are often called choppers, slammers, ’gators, blue dogs, or old yellow eyes. Middle weights are referred to as harbor blues, school blues, tailors, or rats. Little guys and young of the year are nicknamed snappers or cocktail blues.

Bluefish appear on the far eastern end of the Island in early May as water temperatures rise into the low fifties. These early arrivals are considered the northernmost bluefish post-spawning contingence in the North Atlantic. Some anglers speculate these fish have migrated up the coast from their overwintering grounds in the Carolinas. Personally, I think it’s more likely these are blues that dropped away from the Island in the chilly waters of fall, electing to winter over in warmer deep water just offshore.

You’ll find these early-bird blues on Chappaquiddick at East Beach, Cape Pogue Gut, and the ever-popular Wasque, where a long cast on an ebbing tide produces like few other locations. With the wind hanging to the southwest, springtime blues spread westward with rising water temperatures, reaching north shore locations such as Lake Tashmoo in Vineyard Haven and out to Middle Ground off West Chop. The latter was the backdrop for Island author John Hersey’s well-known book Blues (Vintage, 1988). In warm years, by the second week of June, they are apt to be all the way up-Island to Menemsha, Lobsterville, out to Devil’s Bridge, and ’round to Squibnocket. And back at Norton Point in Edgartown on the east end.

Once established, blues remain active into October. If weather patterns continue, in a few years they may still be around into early November. Typically, they feed on moving tides between midmorning and early afternoon, churning the water white in a feeding frenzy known as a blitz. If you miss it, fear not, they are apt to be back near twilight. Now, none of this is to say blues are never caught at night. On occasion they are, and one place to search for them under the stars is down current from a school of menhaden.

I tell you that from personal experience. That’s where, many years back, I hooked my largest blue, a touch over thirty-seven inches in length. Twice it bit short on a long white Lefty’s Deceiver before latching on solid in the heat of an August night. As soon as I felt its strength, I knew it would be an all-out war. After losing an enormous amount of line, I struggled mightily to draw the blue demon back. It took forever to land, revive, and release that beast. And it was only in the aftermath I noticed that the handle on the fly reel was bent and the spool now rubbed against the frame. The reel was cooked.

Today, bluefish are in low abundance along the entire Atlantic coast. Their coastal population peaked between the late 1980s and 1993 before dramatically decreasing. It rebounded a bit in 2009 only to drop off again, and has since remained modest at best. Barring an unforeseen miracle, 2025 is unlikely to be a great year for blue fishing.

It is widely believed that the bluefish population is cyclical in nature, going from boom to bust every forty years, with other anglers saying it’s every ten years. The reasoning behind this cyclical idea, however, has never been established. Regardless, one thing is for sure: overfishing has played a role in their decline. For many years there was absolutely no limit on how many blues anglers could legally kill in a day. And people were known to catch upwards of seventy a day just because they could, only to

end up throwing the carcasses in the dumpster back at the dock. It bordered on a massacre.

As the bluefish population declined sharply in the early 1990s, however, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) finally pushed for a ten-bluefish-a-day limit. At that time, I was a recreational advisor to the ASMFC’s bluefish management plan and was present in the room during a large public hearing in Maryland when the subject hit the fan. The notion of only ten blues a day was hotly debated, felt by some as far too restrictive. Thankfully that measure passed, and since then the limit has gotten tighter with passing years. Today the Massachusetts limit is three blues a day per angler; or five a day per angler from a boat for hire.

Whether the catch comes from shore or the open seas, bluefish that end up on the dinner table often earn high praise. But proper handling is an essential part of making the meal a success. Here are a few thoughts on getting the best out of your fresh-caught fish.

Small blues are known to taste better than the big ones. So, I suggest keeping blues no larger than five or six pounds. As soon as the fish is landed, remove the hook using pliers, never your hand. Believe me, the blue’s sharp teeth have sent folks to the emergency room. Next, either cut through the isthmus between the gills or cut off the tail before holding the fish over a bucket or the side of the boat to allow it to bleed out completely. Then immediately chill it in a cooler. If you are on the beach without a cooler, bury your catch in wet sand. Never just heave it on the beach where the sun and gulls can degrade it.

Upon getting home, promptly clean and fillet your catch, removing the red line that runs down the center of each fillet. This reduces any gamey flavor. For the same reason, you could also remove red lines elsewhere in the meat. Skinning the fillets also helps produce a milder flavor. Since bluefish doesn’t freeze well, plan on it being fish du jour.

On the internet you’ll find a slew of recipes to prepare and cook your catch: from soaking the fillets in milk; basting in white wine, lemon, and lime; marinating in a vinaigrette; liberally coating in melted butter; and even soaking in gin. That would be the fillets, not you.

Whether you’re searching for blues to eat, or just for the thrill of landing, they are rarely difficult to catch once located. All types of salty gear work – spin, fly, plug, or bait. Although in every case a short wire trace at the end of your line is a wise idea, or risk having a bluefish bite off your line.

Now, if you are looking for maximum fun, hands down poppers are the most exciting way to fish. Big, small, red, white, pink, or blue – doesn’t matter, poppers drive blues crazy, prompting explosive, heart-pounding strikes. And should your blue repeatedly miss your popper, keep the faith and keep reeling. Those wild-eyed fish are apt to grab right at the end of the retrieve. And the reverse is true as well. Don’t be surprised if a blue slams your popper the instant it hits the water. I assure you it can happen. Many a Wasque surfcaster has heaved a plug a mile out into the rip only to have it walloped upon landing.

How is that possible? Back in the 1960s at the NOAA Fisheries laboratory in Sandy Hook, New Jersey, scientific research was done on bluefish by animal behaviorist Bori Olla. The blues were housed in a 32,000-gallon saltwater aquarium and observed day and night. If mummichogs, small prey fish, were thrown down the tank, blues looked up, spotted them flying overhead, then dropped back like Willie Mays and caught them as they landed, proving blues have good eyesight both in and

out of the water.

Here’s another couple of interesting facts from those studies. Bluefish appeared totally fearless, but loud noises, such as motors or an anchor hitting the water, spooked them, causing them to stop feeding and to descend to the bottom. So, it was concluded that it’s best to approach blues carefully.

Researchers also noted that when blues were served baitfish, they immediately grabbed any baitfish in sight. When the blues got full, however, they switched gears, targeting the biggest baitfish they could find. I have no idea why, but it’s what was observed. So, if the blitz goes for a time, you might want to try casting out a larger lure. Perhaps even that huge, ugly plug you bought last Christmas from the bargain bin at the tackle shop. It could be pure magic.

Given how aggressively blues feed, many anglers assume blues strike anything you throw at them. And there are times when that does seem to be true. I remember a school of harbor blues chewing things up on the incoming tide in Menemsha Harbor. Myself and others threw every fly we had and the blues ate them all with gusto. Spying a small plastic tube on the sand, euphemistically known as beach whistle, I threaded it on my line and attached a hook on the other. Wham – on the second cast a blue crunched it.

In Robert Post’s much-loved book Reading the Water: Adventures in Surf Fishing from Martha’s Vineyard (Globe Pequot Press, 1988), legendary Island angler Robert Germani, who fished restlessly day and night, shared his thoughts on the bluefish’s palate. In those pages, Germani reported that on one occasion he tied a chorizo sausage on his line fully expecting bluefish to devour it. Astoundingly, they didn’t touch it. Blues not attacking meat? What was going on?

Realizing further experimentation was required, another time Germani tied a five-inch plastic toy boat on the end of his line and cast it out to find that skipping it back over the waves produced pounding strikes. Blues smashed the tiny boat to smithereens, much to the chagrin of neighboring anglers. Now, you are free to draw your own conclusion from all this. Do bluefish simply dislike chorizo? Or maybe it was never about the meat and always the motion.

Unfortunately, it seems that the odds of seeing a bluefish blitz this season are low, but hope springs eternal. Be sure to have a few plugs or flies ready with a wire tippet. You never know when you might run into these Rambos of the rolling seas.