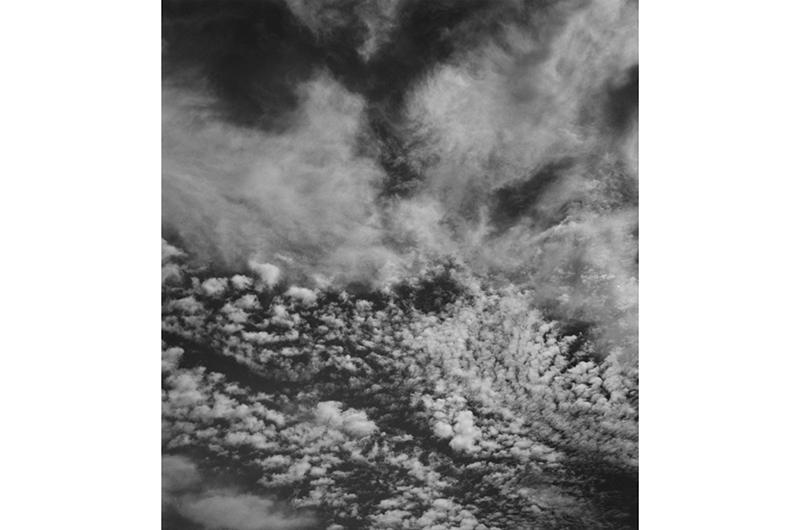

Living in a color-saturated world of screens, one might not imagine the intricacy and dynamism possible in black-and-white photography. Yet for the past five decades, artist Mariana Cook has made a life of creating vibrancy in photographs shot on medium format film cameras in natural light and developed in her darkroom on silver gelatin paper. With the constant evolution of technology, she has never strayed from her traditional process within the medium.

“I wouldn’t be myself unless I made photographs,” said the artist, who splits her time between New York City and Chilmark while also traveling the world to take photographs. And now, as preparation mounts between Cook and her collaborators for an expansive exhibition in Basel, Switzerland, in 2026 to showcase a series she has developed over the course of a decade, a look back at her career displays dedicated work and consistency of quality.

Growing up in New York, her family’s art collection provided opportunities for early contemplation of composition and expression. Treasured paintings, such as Willem de Kooning’s The First of January, provided Cook with breaths of color and organic shape. In 1958, when Cook was three years old, her parents built a home in Chilmark. As she grew older, the family spent every break she had from school on the Island, chartering a four-seater plane from LaGuardia Airport for $35 each way. Time on the Island in the salt air and oak forests, with fishermen and farmers, provided her the sensorial development of a young artist. When at age sixteen she took her first photography course at Exeter Summer school in New Hampshire, the medium became her translator. She finally had the tools to bring out her interior world.

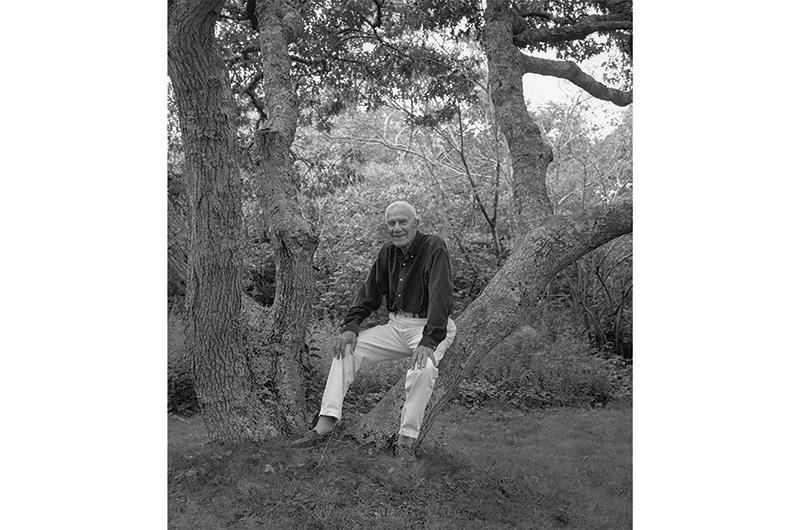

In 1978, Cook, a recent college graduate, visited her father’s first cousin Katharine Graham, the then-publisher of The Washington Post, in her Lambert’s Cove home. It was there that Graham suggested Cook study under her friend, photographer Ansel Adams. Adams was seventy-six at the time, had had a famed career, and continued to work out of his Carmel, California, home. Adams took Cook on as a mentee, teaching her technical skills and critiquing her prints. For five years she traveled to California to work intensively by his side or corresponded with him from New York. As fast friends, the two discussed both art and life and remained close until his death in 1984. His great mentorship and friendship helped cement photography as her life’s pursuit.

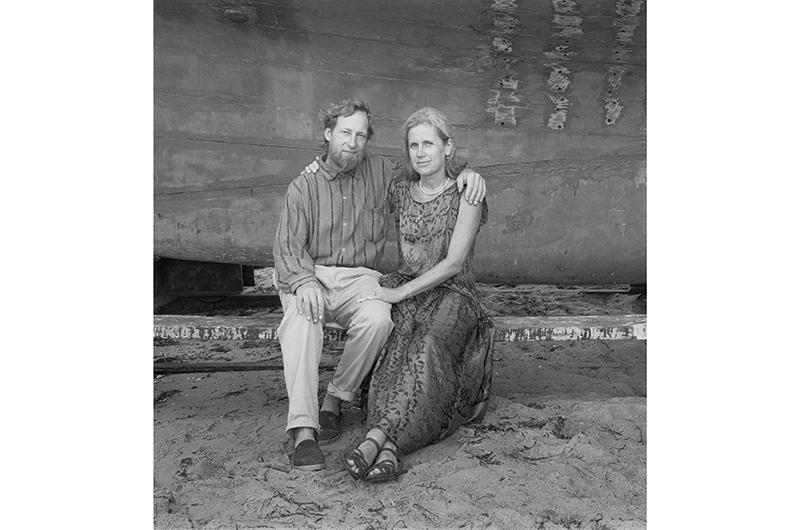

Her subject matter developed alongside her technical process. While Adams’s work focused on landscapes, Cook initially applied his teachings to portraiture. In 1983 she was commissioned to take a portrait of a renowned rare book dealer and his wife, and was introduced to their son, Hans P. Kraus Jr., a young curator of early and rare photography. It wasn’t until 1990 that their kinship became undeniable, and when Kraus visited the Vineyard from New York, Cook was pleased to find he could traverse both urban and rural worlds with her. In 1991, it was on the Island that he proposed.

With both of their lives committed to photography, it may not be a surprise that their daughter Emily, now an adult and living in London, has made a successful career in art as well. “She’s rebelled,” Cook laughed. “Emily, of course, embraces color. She’s a painter.”

In a family so immersed in art, with Kraus providing context in photographic history and Emily with contemporary gestures in color, Cook has progressed diligently on her path. In her career she’s published twelve books with the thirteenth in the making, exhibited nearly forty solo shows, and contributed work to countless others, including on-Island at Tanya Augoustinos’s A Gallery, and in galleries across America, the United Kingdom, and Europe. While her body of work is wide ranging, threads of inspiration through notable projects have led to her forthcoming exhibition.

In portraiture, Cook would meet one interesting character and take their recommendations for whom to photograph next. In this way she worked thematically, developing a series of portraits of Fathers and Daughters, for example, or Couples – both published as monographs by Chronicle Books in 1994 and 2000, respectively. The latter series featured a 1993 image (though it was not published in the book) of the Island’s own Nat and Pam Benjamin, as well as a 1996 portrait of Barack and Michelle Obama in their Chicago apartment. The image has been republished in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and elsewhere to illustrate the strong bond and base of love between the Obamas as a political force.

In exploring new themes, she focused on professions. “The Vineyard has these treasures of people who have a bird’s-eye view of their field, and they know who has really made a contribution that has lasted over time,” she said. Anthony Lewis – a West Tisbury summer resident, Pulitzer Prize–winning legal journalist, and advocate for First Amendment rights – introduced her to subjects for her series titled Justice (Damiani, 2013), capturing faces of the human rights movement. A conversation with Chilmark summer resident Bob Solow – a Nobel Laureate and awardee of the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work in economics – led her to the faces in his field, which she captured for Economists (Yale University Press, 2019).

In each portrait session, Cook waits for the subject’s own psychology to appear, easing back into themselves and forgetting, momentarily, to pose. “I always feel that if I’ve made a successful portrait that it’s a gift from the subjects. I don’t manipulate people or calculate. I don’t know ahead of time what it is I want to portray,” she said. An interesting career or background might bring them in front of her camera, but what she uncovers there is what makes an image strong.

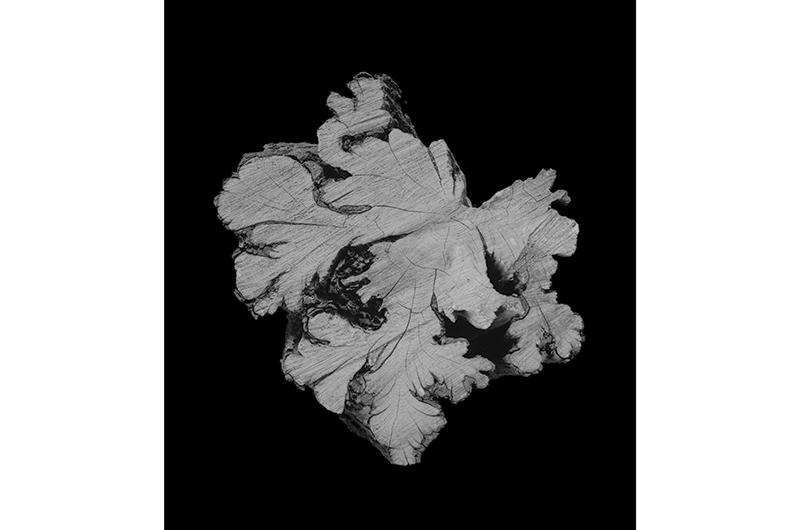

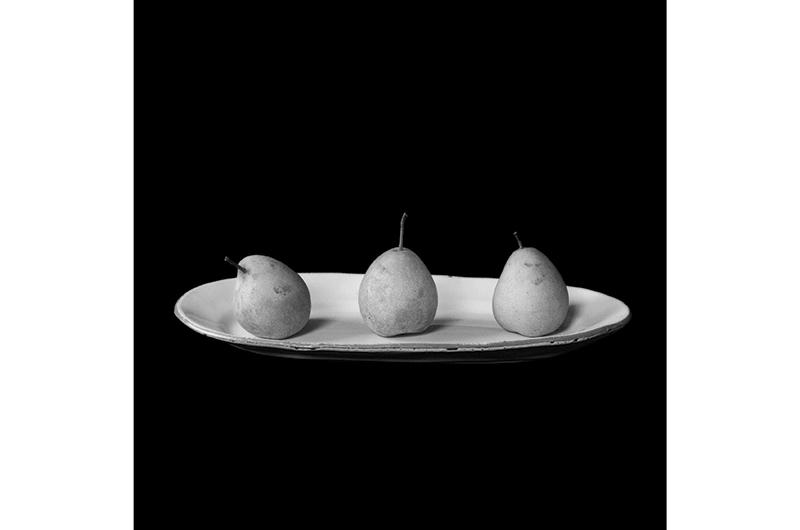

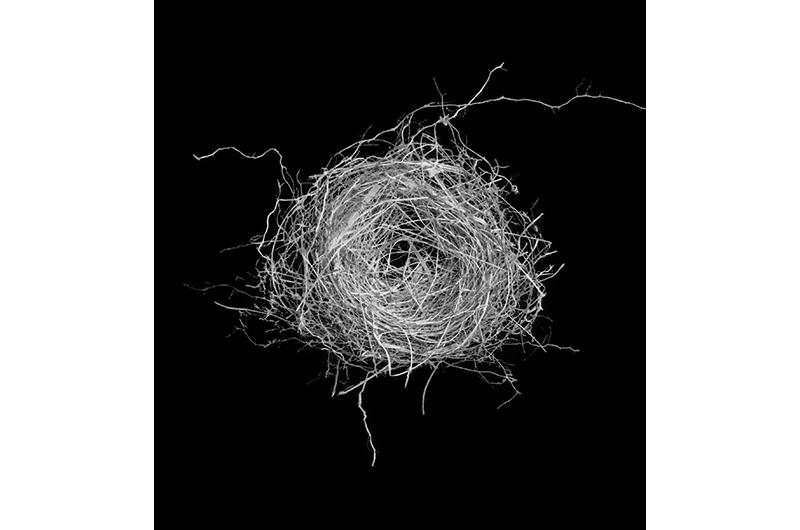

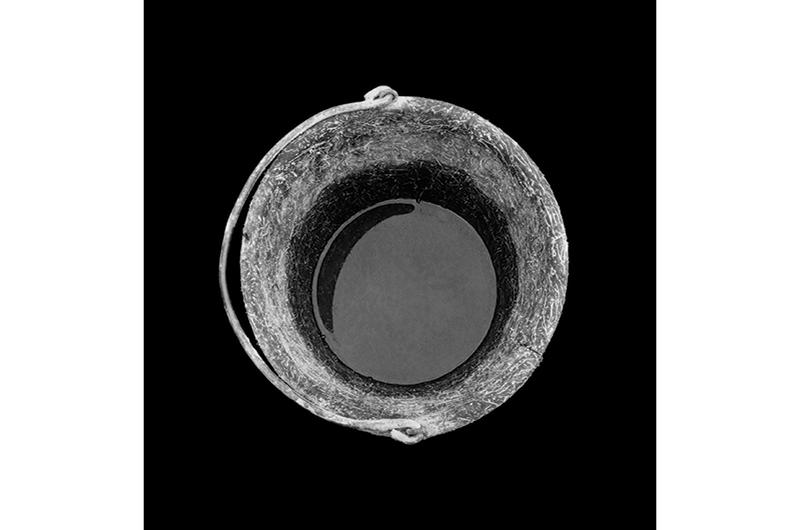

While formal portraits remained a constant throughout her career, she began to focus on the everyday objects around her, photographing the still lives that became her series Close at Hand (Quantuck Lane Press: W. W. Norton, 2007). With the stark contrast of a black velvet backdrop, the viewer is invited to look closely at the marks of wear on a stonemason’s bucket, perfectly formed beech mushrooms, or light on folds of silky cloth. “Objects aren’t objects,” Cook observed, “they become subjects.” In the same way, when Cook comes across a subject out of doors, such as an oak branch shrouded in lichen, or a deer’s antler lying as it fell, she has the same intuitive sense that this subject might offer her a gift.

This was true when Cook began photographing stone walls in 2002, her first landscape project, nearly twenty years after Adams’s death. Each stone wall offered her something novel in its construction, age, or the landscape it moves through. She came close enough to capture texture, or she climbed to a vantage point that allowed the expanse of a patterned wall system to unfurl in her frame. She traveled the world to visit stone walls, and when she had gathered enough material, her book Stone Walls (Damiani, 2011) was published.

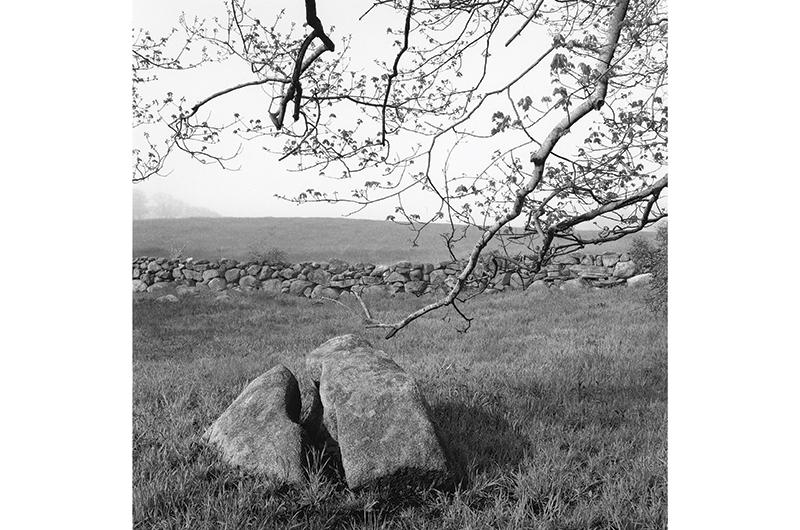

Dining at The Beach Plum Inn in Chilmark one evening in 2013, lamenting that she missed being out in the field and musing on what project might occupy her next, a friend bellowed “glacial erratics,” gesturing emphatically to the boulder-studded lawn outside.

So began a new investigation of something that had been long in her gaze.

The term glacial erratic refers broadly to rock moved from its original location and deposited in a permanent position by an ice sheet. “They have a magical aspect to them,” she said. “They look out of place in the landscape, destined to be foreigners forever. They’ve been where we see them longer than anything we see around them, and yet, they are not native to where they rest.” These stones, ordinary to an up-Islander and data points to geologists, were ideal fodder for Cook’s photographing as, in her way, she began to look deeply at something commonplace. “My erratics are portraits,” Cook said, with characteristic care for the subjects she takes on.

Beyond the Vineyard, she worked with geologist guides in remote locations to find these errant stones in landscapes they inhabit. She visited Yosemite National Park in California, went as far south as Patagonia and New Zealand, and to colder climes, such as the Burren in Ireland, the Faroe Islands of Denmark, and Iceland with its active glaciers. In Switzerland, where the Alps are home to much glacial movement, Cook’s work has recently found resonation and been admired.

Ladina Florineth, proprietress of Villa Flor, a village inn in eastern Switzerland, was introduced to Cook’s work via her book Lifeline (Ivorypress, 2017) and an accompanying exhibition in Madrid, Spain, the same year it was published.

Florineth curated an exhibition of Cook’s work to hang in the villa over the course of 2023. The inn is a destination for artists, and exhibitions hang for one year so annual guests have a chance to take in each collection. Raphael Suter, director of Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger, a foundation dedicated to supporting contemporary art and culture in Basel, Switzerland, became enamored with the photographs he encountered on his stay. His proposal for a grand exhibition of her work at the foundation is now well into production, slated to run from November 20, 2026, to February 14, 2027.

The exhibition of seventy-two photographs of glacial erratics is titled Out of Place – Out of Time. Evolving designs for the space will organize Cook’s images by location, with a room dedicated to stones found on Martha’s Vineyard. Beda Achermann, a revered creative director, editor, and designer, is planning the exhibition space. Achermann is also composing an accompanying book documenting the entire project.

A film has been commissioned to be on view in the exhibition as well, directed by Evelyn Schels, a German filmmaker whose documentary work on artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Georg Baselitz made her a clear choice to lead the project. Schels and her crew traveled with Cook this past winter.

Of the resulting film, Cook explained, “It’ll be a mini biography of me as a photographer and all the work I do. We were in so many different places and she discovered so many different processes.” They spent time in her studio and darkroom in New York, and visited the Island, where Cook led them to some of her favorite stones to capture footage of her photographing new details of her subjects.

An exhibition of this size, with the accompanying book and film of the same title, signals an earned recognition. It also requires a pace and prolificacy of work that the artist has well established. Cook’s studio in New York buzzes daily with assistants who possess the detail-oriented organization required to maintain her archive of over 7,000 photographs.

But no perfect print, exhibition, or accomplishment would mark an end note for Cook. She’s already begun her next visual investigation in landscapes, this time focusing on trees, where she’ll uncover great depth in the simple theme. Making images will propel her across distances in search of subjects, and, as ever, back to her darkroom, where her way of seeing is made material.

The print version of this article incorrectly stated who proposed the exhibit at the Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger foundation, which was director Raphael Suter. We apologize for the error.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)