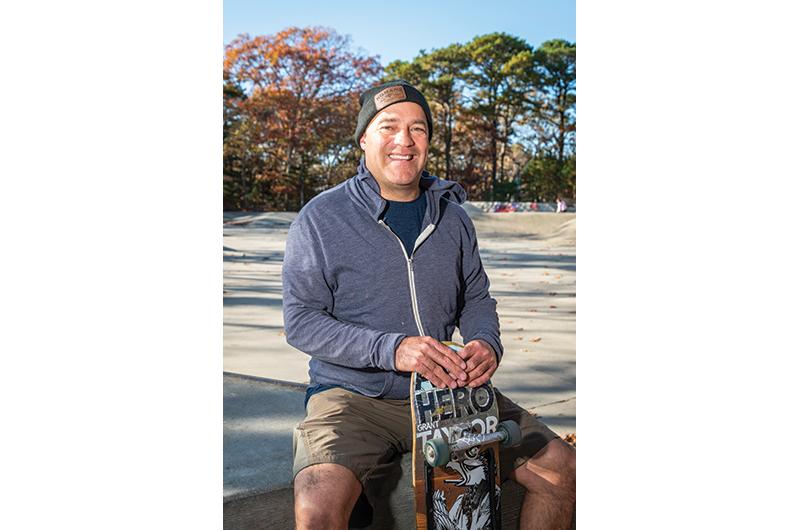

Before Nick Briggs was teaching himself nose grabs and showing kids how to kickturn, he was just a kid himself, growing up on the Vineyard, looking for a safe place to skate.

It was 1988 and Briggs was nine. “There was a crew of older kids in Vineyard Haven and I would see them skate around town and it looked fun. That’s how most kids started [skateboarding] back then,” he said.

“When I saw someone ollie jump on a skateboard up a curb while moving down – I mean, it just looked so cool,” he continued. “Me and my buddies, we learned from the older kids. Skateboarding is a sport where older kids help younger kids.”

As he entered his own teenage years, however, Briggs realized there were few places for teens to test out their skills with friends. Some people would head to “The Ledge” – a potholed, uneven stretch of sidewalk fronting a low wall on Center Street in Vineyard Haven – but the area was often crowded with people waiting around for their turn. Others created makeshift bowls and ramps in driveways or set up camp in semi-empty parking lots and loading docks until someone would chase them away. “Back then we would even sometimes take the Island Queen to skate off-Island at the plaza, the mall,” he said.

Most of the time, though, Briggs and his buddies would just skateboard through Vineyard Haven, up and down sidewalks, and tool around the Steamship Authority parking lot. The only problem: it wasn’t exactly legal. Vineyard Haven and Oak Bluffs have bylaws preventing skateboarding in crowded areas. In the former town, that meant it was prohibited anywhere in the downtown area, plus around the Tisbury School and the Oak Grove Cemetery.

“Sometimes the police would confiscate our boards and our parents would get called and have to go to the police station to pick them up,” Briggs recalled. Other times, skaters would get summoned to the courthouse for minor citations.

“We really needed a skatepark on the Island,” he said, “because you weren’t allowed to skateboard downtown.”

It was a topic that Briggs and his friends – pretty much anyone who eventually picked up a skateboard on the Island, actually – had been casually bandying about for years. On the surface, it shouldn’t have been a difficult goal to accomplish. The Cape had plenty of skateparks; even Nantucket had one of its own. A designated area on Martha’s Vineyard would give kids and adults a safe place to gather. It would mean less going off-Island, less getting into trouble. Still, the process was incredibly slow.

“We worked on it for ten years before we got everything going, and for a couple years it just looked like it was never going to happen,” Rich Hammond, the former treasurer of the Martha’s Vineyard Skatepark Association (MVSA), told Island director Ollie Becker in a 2023 short film about the park. Hammond got involved in the project when one of his kids, who was just eight years old at the time, started catching grief for skating on streets and loading docks. Hammond decided something needed to be done.

In 2003, the wheels of the skating community’s long-going, start-and-stop effort kicked into full gear. That year, construction began on the Island’s only skatepark, across from the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School in Oak Bluffs. It opened to the public shortly thereafter. For Briggs, Hammond, and so many others who helped bring it to fruition, their efforts have paid off many times over. Not only did they welcome a new generation of skateboarders on the Island in the past two decades, they’ve also been hitting the rails and ramps they helped build ever since.

But let’s take a step back for a moment. We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Every skater has a how-I-got-started story. Erik Albert, the longtime president of the MVSA that today oversees the skatepark, isn’t any different.

“I have the same skateboarding story as so many other people,” he explained. “Traditional sports just didn’t speak to me. Team sports and organized sports where you have to do it this way or that way – you know, it just wasn’t for me.”

He also liked the blasé do-it-yourself attitude that skateboarders brought to their sport. “There was no internet and no YouTube, so it was something I tried to figure out on my own. That’s one of the beauties of skateboarding: everyone tries to figure it out their own way.”

Albert grew up outside of New York City and spent summers in Oak Bluffs. Eventually, he moved to the Island year-round, where he and his wife now run the Oak Bluffs Inn. But in those early days, he brought that DIY spirit and ingenuity with him to the Island. “I had some friends and we used to have benches that I would put on the rack of my car – a Honda Accord with a roof rack on it – and we would set them up at tennis courts or the Park & Ride and make pop-up skateparks,” he said.

Eventually he met Briggs and the two became friends. “Skateboarders just find each other. You find the spots. You know what to look for,” he said.

In 2002, Albert, Briggs, Hammond, and several others helped found the MVSA, a nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation. The goal of the new nonprofit was to legitimize the skateboarding community’s cause and convince the public of the need for a skatepark. But whereas previous efforts had eventually failed, this time there would be progress. For one thing, years of pleading their case had gotten more people involved. In addition to the skateboarding community, Island leaders and non-skaters signed up to help.

“In that whole process of trying to build a skatepark, we educated the public on how it could be such a good thing,” Briggs said of the early years. “People always knew that youth activities need to be supported and, hey, you have to start somewhere.”

One of the earliest community members to lend her support was Elaine Barse, who at the time ran a little surf and skate shop on Spring Street in Vineyard Haven called The Green Room. (The store, which has been in business for thirty years, relocated to Main Street many years ago.)

“I’m not a skateboarder, but obviously I have been a part of this skateboarding community on the Vineyard,” Barse explained. She liked that the sport didn’t require a lot of equipment, that anyone could pick up a board and get started. But the biggest reason she joined the cause back then, she said, was that “so many people were saying, ‘Somebody should do something, somebody should do something.’ And I thought, ‘What can we do? What can I do? How can I help?’”

Barse and her fellow nonprofit members fanned out across the Island, attending town and school committee meetings in search of a place to build. Land was the biggest obstacle. Not only was it expensive and hard to come by on an island, but no town wanted to shoulder the responsibility or liability of maintaining a skatepark. That finally changed when Margaret “Peg” Regan, then-principal of the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, stepped in.

Regan had the idea of shaving off a small parcel of land located on the Edgartown–Vineyard Haven Road, across the street from the high school. There was no YMCA there at the time, just the Martha’s Vineyard Ice Arena, which was surrounded by woods. The area was unlikely to be the site of future high school expansion, since it was situated across a busy stretch of road. Instead, Regan proposed reserving the land for a skatepark if supervision and liability issues could be resolved.

“We got really lucky when we found that piece of land across from the high school,” Briggs recalled. “We were looking at land behind the high school, a track parking lot, and we were looking at a lot of different places and [Regan] said, ‘How about that one?’”

After hashing out the details, the high school committee deeded the land to the town of Oak Bluffs, which agreed to insure the park and take care of trash removal – with one caveat: the town didn’t want to foot the bill. That’s where the members of the skatepark nonprofit jumped back in. They visited each of the remaining five towns and convinced them to collectively kick in $20,000. That was followed by an anonymous $20,000 donation. Soon, more donations followed suit, including $5,000 from the Permanent Endowment Fund for Martha’s Vineyard (now the Martha’s Vineyard Community Foundation).

At a May 2002 high school committee meeting, Barse expressed her excitement for getting the wheels turning on the project. “It’s been a real group effort – a lot of people who helped us get through the political process. Now we can move on to more tangible things like designing the park,” she said.

MVSA tapped East Coast Ramp Design in Connecticut to design and build the 150-by-150-foot skatepark that would include a halfpipe, a street course, and a mixture of wooden and cement ramps. In the true spirit of the community-led project, Island contractors and builders contributed materials, expertise, and their time. Parents, kids, and plenty of skaters picked up hammers and shovels. Everyone did what they could.

Today, the cohort that helped put the skatepark together is some twenty years older, certainly a little grayer, but still learning new tricks. Albert is fifty-five with a daughter and son, both now in their twenties. Briggs is forty-five and the father of three children: Clover, fifteen; Sawyer, twelve; and Wren, nine. He started bringing all three of his kids to the park before they could walk.

“I brought Wren and Sawyer when they were in a stroller when they were baby-babies. They would just hang out in the stroller in a blanket, and then they would crawl and play in the sand,” Briggs said. Eventually, they started pushing around a board.

Today, the family goes to the park to skate – or, in the case of Wren, to Rollerblade or scooter too. “Having the skatepark makes it an easy, fun activity. It’s free. It’s the best,” said Briggs. “All you need is a skateboard. It’s the cheapest sport going.”

His children are far from the only young ones there. In 2007, skateboarder Eliot Coutts started the Martha’s Vineyard Summer Skate Drop-In Program for kids with the help of his now-wife, Alexandra Bullen Coutts, and friend, Zeb Weisman. Coutts, who grew up on the Island and now has three children, said he was inspired to start the program after attending a Pennsylvania skateboard camp when he was younger. It was one of his most memorable childhood experiences.

“I knew I wanted to create something for kids on the Island,” Coutts said. The clinic runs for eight weeks each summer, Monday through Friday, from 8:30 a.m. to noon, and is open to kids ages seven to thirteen.

A few years ago, Coutts stepped down from running the program, but still serves on the MVSA board alongside Calder Martin, Jonah Miller, Briggs, Albert, and Barse. The latter served as president of the board until 2015, when Albert took over.

Though the board members host occasional formal meetings to discuss operations, they also see each other casually all the time. They skate together. They’re friends, Albert said. It’s that spirit of camaraderie and DIY that has helped sustain the skatepark. Over the years, they’ve hosted fundraisers, bake sales, and concerts. They’ve sold T-shirts to raise additional funds. And they’ve maintained a positive relationship with the town of Oak Bluffs. “Today they removed some graffiti for us. I just have to say, we love the town,” said Briggs.

But around 2013, when the skatepark began to show its age, this group knew they couldn’t go it alone. They once again reached out to the community for help.

When the park was initially designed and built, the industry standard mandated wood ramps be covered with Skatelite, a durable paper-composite surface material tough enough to withstand skateboards. A decade on, the wooden ramps were warping, the price of Skatelite had doubled, and the concrete needed to be smoothed.

In 2016, the MVSA received a $252,172 grant from MV Youth, a nonprofit that provides educational scholarships and funds local organizations, to make such repairs. The grant also helped MVSA to install lights and fund youth programming, including free helmet days and Skate Jams, featuring live music and demos from visiting skateboarders. It’s been relatively smooth rolling ever since.

Looking ahead, Barse said there’s still work to be done. “Like anything, we’re always talking about sustainability,” she said. “If we don’t keep contributing, it won’t just magically keep existing. We are always looking for people to help and people to get involved with the park.”

Albert, for his part, is filled with gratitude for how much the sport, the park, and skating on the Vineyard has grown. “Skateboarding is the best. It’s freedom. It’s all that. It’s artistic expression. It’s taking me back. It’s a time machine taking me back to when I was a kid,” he said.

“I still learn new tricks at fifty-five years old,” he added. “Skateboarding keeps you young. You don’t stop skateboarding because you got old; you got old because you stopped skateboarding....The progression, the learning, the hype, the camaraderie. Everyone’s happy when someone lands something new or spectacular. Everyone cheers for everyone, even if it’s a contest. Everyone’s on the same team.”

As for his own team, the one he helped build more than two decades ago and has remained dedicated to ever since, he has just one goal.

“Keep on keeping on, that’s really it,” he said.